Checked Bags: a Litany of Potentially Explosive Things

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alaska Trip Clothing and Gear List

Alaska Trip Clothing and Gear List A list of suggested clothing based on our experience is indicated below. Mark all clothing with indelible ink. Campers will have the opportunity to do laundry on the trip. We recommend wrinkle-resistant clothing that dries quickly. “Good” clothes are not recommended. ALL ALASKA CAMPERS MUST HAVE A PASSPORT OR PASSPORT CARD TIPS ON PACKING: Campers are allowed only ONE duffel bag (size 26” x 42”) Everything - with the exception of your sleeping bag, sleeping pad, pillow, light blanket and any items kept in your daypack - must fit into your duffel bag. You can best organize your duffel by compartmentalizing your clothing. Group similar clothes, such as t-shirts, and place them into plastic bags. Feel free to use bags you have around the house instead of buying new bags. The plastic bags will serve a dual purpose; to help you keep your clothes sorted and easy to reach, and as added protection against moisture and accidental spilling. TIPS ON IMPORTANT GEAR: SLEEPING BAG: You will need a good summer bag with synthetic fill. No goose down or cotton filled bags are allowed. Synthetic will work well when wet and is less expensive than goose down bags. We recommend a synthetic, 20-degree bag. HIKING BOOTS: Boots should extend over the ankle for support. The upper portion should be made of nylon or leather and should have the capacity to become waterproofed. The boot should be worn for at least 6 weeks before the trip in order to prevent blisters. They should be waterproofed before the trip. -

View Packing Lists

BOLD & GOLD EXPEDITIONS GENERAL PACKING INFORMATION All participants are responsible for bringing the items on the following list with them to check-in. Please check with your teen that every item is actually going into their pack before leaving home. Please take note of additional items necessary for your specific programs (see pages 12-18 in the handbook). The quality of clothing and equipment can have an enormous impact on the health and happiness of participants. When selecting equipment, size and weight can be important. BOLD & GOLD can provide many of these items, including clothing from an extensive outdoor clothing lending library; please call with any questions or to rent any gear. PACKING Since your teen will be carrying their own equipment as well as a portion of the group’s food and gear, choose personal gear that is lightweight, warm and easily packed. All items should be packed in a backpack that has a minimum capacity of 60-70 Liters, and should be capable of carrying 25-30 lbs. It should be an internal frame design and have adjustable hip and waist belts. If you will be renting a backpack from BOLD & GOLD, please bring gear in a duffel bag to check-in. CLOTHING Your teen will be living outside, so having the right clothing is important for their comfort and safety. There could be rain, snow, hot sun, or strong winds on your course. Our clothing list reflects the importance of the “layering” principle. Dressing in several light layers rather than one heavy layer allows them more flexibility as the weather and workloads change. -

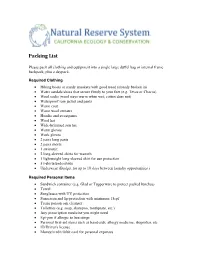

Packing List

Packing List Please pack all clothing and equipment into a single large duffel bag or internal frame backpack, plus a daypack. Required Clothing • Hiking boots or sturdy sneakers with good tread (already broken in) • Water sandals/shoes that secure firmly to your feet (e.g. Tevas or Chacos) • Wool socks (wool stays warm when wet; cotton does not) • Waterproof rain jacket and pants • Warm coat • Warm wool sweater • Hoodie and sweatpants • Wool hat • Wide-brimmed sun hat • Warm gloves • Work gloves • 2 pairs long pants • 2 pairs shorts • 1 swimsuit • 2 long-sleeved shirts for warmth • 1 lightweight long-sleeved shirt for sun protection • 5 t-shirts/undershirts • Underwear (Budget for up to 10 days between laundry opportunities.) Required Personal Items • Sandwich container (e.g. Glad or Tupperware to protect packed lunches) • Towel • Sunglasses with UV protection • Sunscreen and lip protection with minimum 15spf • Tecnu poison oak cleanser • Toiletries (e.g. soap, shampoo, toothpaste, etc.) • Any prescription medicine you might need • Epi-pen if allergic to bee stings • Personal first-aid items such as band-aids, allergy medicine, ibuprofen, etc. • ID/Driver's license • Money/credit/debit card for personal expenses Required Equipment • Laptop computer with wireless connectivity, sufficient battery life, MS Office, and JMP Statistical Software (JMP is available through your home campus, you must have it loaded and tested for functionality before arrival to the course) • Small tent (1-2 person) with durable rainfly and footprint tarp • Warm sleeping bag (Temperatures may dip below freezing: if your sleeping bag is not rated at 20° F or colder, you will need to bring a sleeping bag liner as well.) • Packable inflatable sleeping pad (e.g. -

Cargo Specials Bag & Pack Specials Dry Bag Specials Surplus Specials

BAG & PACK SPECIALS Sales Flyer 1 - 8 Quick Order Form 37 - 40 CARGO SPECIALS Sales Flyer 9 - 21 Quick Order Form 41 - 46 DRY BAG SPECIALS Sales Flyer 22 - 31 Quick Order Form 47 - 48 SURPLUS SPECIALS Sales Flyer 32 - 36 Quick Order Form 49 - 50 SALES VALID 1/17/2021 - 3/31/2021 Table of Contents | Winter 2021 800.523.4332 | [email protected] 2021 Winter Expo BAG & PACK SPECIALS Your one stop shop for your favorite Fox bags and packs that excel in any application. SALE VALID 1/17/2021 - 3/31/2021 NEW Quick Order Form Available BAG & PACK SPECIALS CONTACT FOX 2 SALE VALID: 1/17/21 - 3/31/21 800.523.4332 / [email protected] NEW A multi-functional pack that easily converts from a suitcase to a backpack in seconds making it ideal for travel $ SLATE GREY Introductory 49.90 Sale $ 54-541 39.90 Size: Compartments: 19.25” x 13.5” x 5” (Expandable - 7”) 3 Compartment Configuration Outer Shell: Lining: Water-resistant polyester Durable P.U. coated polyester Zippers: Nylon coil self repairing with hardened rubber tips 1 4 CLOTHING BACK PANEL COMPARTMENT POCKET Expandable with butterfly To conceal detachable fold-out feature / 3 mesh pockets shoulder straps 2 5 ELECTRONICS SIDE CARRY 1 COMPARTMENT HANDLE Padded laptop and tablet sleeve Can be carried as a briefcase when with 3 accessory pockets shoulder straps are concealed 3 6 ORGANIZER LUGGAGE HANDLE COMPARTMENT SLEEVE 2 document sleeves with 2 Slips over most luggage handles zippered pockets for ease in use during travel Quick access pocket on next page 2 3 4 6 5 BAG & PACK SPECIALS CONTACT -

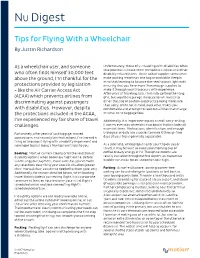

Tips for Flying with a Wheelchair by Justin Richardson

NU Digest Tips for Flying With a Wheelchair By Justin Richardson As a wheelchair user, and someone Unfortunately, those of us traveling with disabilities often lose precious suitcase room to medical supplies and other who often finds himself 30,000 feet disability related items. These added supplies sometimes above the ground, I’m thankful for the make packing more than one bag unavoidable. Keep in mind that learning to balance the need to pack light with protections provided by legislation ensuring that you have more than enough supplies to - like the Air Carrier Access Act make it through your trip occurs with experience. After years of traveling solo, I’m finally getting the hang (ACAA) which prevents airlines from of it, but would encourage the occasional traveler to discriminating against passengers err on the side of caution and practice being more safe than sorry. With that in mind, pack what makes you with disabilities. However, despite comfortable and attempt to seek out airlines that charge the protections included in the ACAA, minimal or no baggage fees. I’ve experienced my fair share of travel Additionally, it is important to pack a small carry-on bag challenges. (I use my everyday wheelchair backpack) that includes all essential items. Medications, identification, and enough Fortunately, after years of lost luggage, missed urological or daily use supplies to make it through two connections, and security line frustrations, I’ve learned a days of your trip is generally a good idea. thing or two about flying with a mobility impairment and now hope to pass along a few tips and tricks to you. -

Duncanville ISD Clear Bag Regulation

Duncanville ISD Clear Bag Regulation Panther Stadium • Old Panther Stadium • Panther Baseball Complex• Natatorium • Sandra Meadows Arena To ensure visitor safety, along with quick and efficient entry into our event venues, Duncanville ISD has instituted a Clear Bag Regulation. This will limit the size and type of bag allowed at all sporting events, performances and entertainment events held at five athletic facilities: Panther Stadium, Old Panther Stadium, Panther Baseball Complex, Natatorium and Sandra Meadows Arena. While Duncanville ISD encourages visitors not to bring bags if possible, the following types of bags are permissible:• Clear, plastic, vinyl or PVC bags (12" X 12" X 6") • Clear, plastic, one-gallon, re-sealable, Ziploc-style bags • Clutch bags approximately the size of a hand (4 ½” X 6 ½”) • Medically necessary items Visitors who bring bags that do not meet the criteria outlined, will not be permitted entrance into the venue. Permitted Bags Large Bags CLEAR TOTE: PLASTIC STORAGE BAG: Clear, plastic, vinyl or PVC Clear, plastic, one-gallon, re-sealable, Ziploc-style OR Small Bags CLEAR OR SOLID COLOR SMALL CLUTCH BAG: With or without a handle or strap approximately the size of a hand (4 ½” X 6 ½”) 4.5” 4.5” OR 3.5” OR 6.5” 4” 6.5” Non-Permitted Bags Printed Pattern Fanny Pack Purse Reusable Mesh or Backpack Plastic Bag Grocery Tote Straw Bag Duffel Bag Large Tote Bag Camera Bags Diaper Bags Cinch Bag Plastic Storage Bag Medical Items or Equipment Visitors with medical items or equipment can enter any main facility entrance to have bags and equipment checked before admittance. -

2011 PRODUCT CATALOG Www

2011 PRODUCT CATALOG BACKPACKS • TRAVEL GEAR • DUFFEL BAGS www.everestbag.com ™ TABLE OF CONTENTS COLORS BACKPACKS 1-7 BLACK DARK GRAY JUNIOR BACKPACKS 7-8 CHARCOAL caNVAS COLLectION 9 GRAY LIGHT GRAY SLING BAGS 10-11 WHITE UTILITY BAGS 12-13 BURGUNDY HYDRatION PacKS 14 MAGENTA RASPBERRY WAIST BAGS 14-15 RED caMERA BAGS 16 PINK BROWN SHOPPING TOteS 16-17 KHAKI BRIEFcaSES 18-20 BEIGE YELLOW DUFFEL BAGS 20-23 LIME TRAVEL GeaR BAGS 24-25 GREEN OLIVE caMO COLLectION 26-27 DARK GREEN WHEELED BacKPacKS 28-29 TURQUOISE ROLLING BAGS 29 BLUE TEAL BLUE WHEELED DUFFELS 30 ROYAL BLUE LUGGAGE 31-32 MIDNIGHT BLUE NAVY CUSTOM OEM 33 PURPLE LIGHT PURPLE © 2011 Everest Trading Corp. All rights reserved. 1045A CLASSIC BACKPACK W/ FRONT ORGANIZER BLACK Classic two-tone backpack. Main compartment and a front NAVY organizer accessible via clamshell zippered opening. RED BLUE PINK BROWN material 600D Polyester dimension 13.0 x 17.0 x 7.0 in. capacity 1230 in3 1045BP CLASSIC BACKPACK BLACK Remake of a classic. Front accessory pocket, internal NAVY organizer, quick access side mesh pocket, and comfortable RED BLUE padded back panel. PINK material 600D Polyester dimension 13.0 x 16.5 x 6.5 in. capacity 1180 in3 1045K BASIC BACKPACK BLACK Mid-size backpack. Spacious main compartment and a front NAVY zippered pocket for loose items. RED BLUE ROYAL BLUE TEAL BLUE LIGHT PURPLE CHARCOAL material 600D Polyester DARK GRAY dimension 11.0 x 15.0 x 5.0 in. 3 DARK GREEN capacity 750 in BROWN KHAKI LIME PINK WHITE 1045KP BASIC PATTERN BACKPACK CHECKERED Identical to 1045K Basic Backpack plus patterns. -

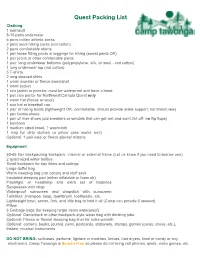

Quest Packing List

Quest Packing List Clothing 1 swimsuit 8-10 pairs underwear 6 pairs cotton athletic socks 2 pairs wool hiking socks (not cotton) 2 pairs comfortable shorts 1 pair loose fitting pants or leggings for hiking (sweat pants OK) 1 pair jeans or other comfortable pants 1 pair long underwear bottoms (polypropylene, silk, or wool - not cotton) 1 long underwear top (not cotton) 5 T-shirts 2 long sleeved shirts 1 warm sweater or fleece sweatshirt 1 warm jacket 1 rain jacket or poncho- must be waterproof and have a hood 1 pair rain pants- for Northwest/Canada Quest only 1 warm hat (fleece or wool) 1 sun hat or baseball cap 1 pair of hiking boots (lightweight OK, comfortable, should provide ankle support, not brand new) 1 pair tennis shoes 1 pair of river shoes (old sneakers or sandals that can get wet and won’t fall off- no flip flops) 1 bandana 1 medium sized towel, 1 washcloth 1 bag for dirty clothes (a pillow case works well) Optional: 1 pair wool or fleece gloves/ mittens Equipment 50-65 liter backpacking backpack, internal or external frame (Let us know if you need to borrow one) 2 quart-sized water bottles Small backpack for day hikes and outings Large duffel bag Warm sleeping bag (not cotton) and stuff sack Insulated sleeping pad (either inflatable or foam ok) Flashlight or headlamp and extra set of batteries Sunglasses with strap Waterproof sunscreen and chapstick with sunscreen Toiletries: shampoo, soap, toothbrush, toothpaste, etc. Lightweight bowl, spoon, fork, and little bag to hold it all (Camp can provide if needed) Pillow 3 Garbage bags (for keeping larger items waterproof) Optional: Camelback or other backpack-style water bag with drinking tube Optional: Fleece or flannel sleeping bag liner for extra warmth Optional: camera, books, journal, pens, postcards, stationery, stamps, games (cards, chess, etc.), frisbee, musical instruments DO NOT BRING: suitcases, perfume, lighters or matches, knives, hair dryers, food or candy or any electronics. -

Ebay Listings for "Wheeled Luggage". Click on the "Buy Now" Link to Purchase an Item

eBay Listings for "Wheeled Luggage". Click on the "Buy Now" link to purchase an item. • 30" Rolling Duffel Bag Wheeled Luggage Suitcase Travel Tote Duffle Bag Free Ship ($36.95) - Buy Now • Tumi Ducati Evoluzione International Carry-On Wheeled Luggage Bag Color Blk ($299.99) - Buy Now • 42" Rolling Duffel Bag Wheeled Luggage Suitcase Travel Tote Duffle Bag Free Ship ($49.99) - Buy Now • Brown Leather 24" Trolley Bag Tote Luggage with Wheels Silver-Tone Heart Accents ($59.89) - Buy Now • 30" Black Rolling Wheeled Duffel Bag Spinner Suitcase Duffle Luggage Carry on ($26.95) - Buy Now • 40" Black Large Rolling Wheeled Duffel Bag Spinner Suitcase Duffle Bag Luggage ($29.99) - Buy Now • NIB! Ricardo Meritage Ultra-Glide 4 Wheel Travel Set ($23.50) - Buy Now • 27" 50LB. CAPACITY ROLLING WHEELED DUFFLE BAG / LUGGAGE/SUITCASE RETRACT HANDLE ($37.93) - Buy Now • RedHead Canvas Luggage Collection - Oversized Wheeled Trunk ($90.00) - Buy Now • Large 42" Rolling Wheeled Duffel Bags Luggage FREE SHIPPING New Heavy Duty 8999 ($56.99) - Buy Now • 40" Black Large Rolling Wheeled Duffel Bag Spinner Suitcase Duffle Bag Luggage ($31.25) - Buy Now • LIPAULT Wheeled Backpack Computer Bag~Chocolate~New With Tags! ($49.99) - Buy Now • 22" 40LB. BLACK W PINK POLKA DOTS ROLLING WHEELED DUFFLE BAG/CARRY ON /SUITCASE ($37.73) - Buy Now • 36" Rolling Duffel Bag Wheeled Luggage Suitcase Travel Tote Duffle Bag Free Ship ($41.68) - Buy Now • NEW FILSON MADE IN USA TWILL WHEELED DUFFLE XL ($314.00) - Buy Now • 25" Black Rolling Duffel Bag Travel Tote Duffle Bag Wheeled -

Comparison of Features, Usability, and Load Carrying Design of Recreational and Travel Backpacks When Considering Travel Applications

Comparison of features, usability, and load carrying design of recreational and travel backpacks when considering travel applications by Zoe Eagle A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Industrial Engineering Program of Study Committee: Richard Stone, Major Professor Caroline Krejci Ellen McKinney Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2016 Copyright © Zoe Eagle, 2016. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ....................................................................................................... iii ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................. iv CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER 2: COMPARISON OF FEATURES, USABILITY, AND LOAD CARRYING DESIGN OF RECREATIONAL AND TRAVEL BACKPACKS WHEN CONSIDERING TRAVEL APPLICATIONS .................................................................................................... 16 Abstract ................................................................................................................................ 16 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 17 Methods ............................................................................................................................... 30 Results -

CLEAR OR SOLID COLOR SMALL CLUTCH BAG with Or Without a Handle Or Strap Approximately the Size of a Hand (4 ½” X 6 ½”)

Katy ISD Clear Bag Regulation for Graduation Ceremonies To ensure safety at Graduation ceremonies, and to ensure quick and efficient entry into our event venue, Katy ISD has instituted a Clear Bag Regulation. This will limit the size and type of bags/items allowed at graduation ceremonies held at Legacy Stadium. While Katy ISD encourages visitors not to bring bags if possible, the following types of bags are permissible: • Clear, plastic, vinyl or PVC bags • Clear, plastic, one-gallon, re-sealable, Ziploc-style bags • Clutch bags approximately the size of a hand (4 ½” X 6 ½”) • Medically necessary items Visitors who bring bags that do not meet the criteria outlined, will not be permitted entrance into the venue. Permitted Bags Large Bags Small Bags - CLEAR OR SOLID COLOR SMALL CLUTCH BAG With or without a handle or strap approximately the size of a hand (4 ½” X 6 ½”) CLEAR TOTE: CLEAR PLASTIC STORAGE BAG: Clear, plastic, vinyl or PVC BACKPACK: Clear, plastic, one-gallon, re-sealable, Ziploc-style 4.5” 3.5” 4.5” 4” 6.5” 6.5” Non-Permitted Bags and Items Solid Color Printed Pattern Fanny Pack Purse Reusable Mesh or Backpack Plastic Bag Grocery Tote Straw Bag Duffel Bag Large Tote Bag Camera Case Diaper Bags Solid Color Solid Color Plastic Cinch Bag Storage Bag Balloons Noise Makers Food/Drink Glass Containers/Vases Medical Items or Equipment Visitors with medical items or equipment can enter any main facility entrance to have bags and equipment screened before admittance. Questions? Contact KatyISD Police Department at 281-237-4000. -

Types of Leather Bags

TYPES OF LEATHER BAGS: Athletic bag: a soft, roomy bag used to carry sporting equipment and apparel to the gym, great trend setters in today’s age. Backpack: a bag that is supported by the shoulders with double handles and lies across the back. Backpacks are supported on either one or both shoulders. 1 Bowling Bag: A bag originally made to hold a bowling ball, this has become a fashion item. Bucket bag: roomy bag shaped like a bucket, usually has an open top and shoulder strap. 2 Doctor's bag: A traditional doctor's bag is a duffel-shaped leather satchel used primarily to carry small medical necessities when making house calls. The classic doctor's bag is flat-bottomed with rounded sides, slightly elongated. Two large handles come together over the top for easy carrying. The mouth of the bag has a collapsible metal frame that springs open when handles are separated and tugged. The gaping mouth makes it easy to see into the bag and extract items. Duffel Bag: A large bag usually used for travel or sports. The name comes from Duffel, a town in Belgium where the thick cloth used to make the bag originated. Duffel bags are often used by sailors, and are sometimes called sea bags in this capacity. All leather Duffel bags are Epic design icons and supreme utility items to own. 3 Feed bag: bag that is used to feed an animal (such as a horse); covers the muzzle and fastens at the top of the head. Messenger Bag: A bag with a long strap to be worn across the body that winds around the chest resting the bag on the lower back.