Locating the Monastery of St. Donnan on Eigg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inner and Outer Hebrides Hiking Adventure

Dun Ara, Isle of Mull Inner and Outer Hebrides hiking adventure Visiting some great ancient and medieval sites This trip takes us along Scotland’s west coast from the Isle of 9 Mull in the south, along the western edge of highland Scotland Lewis to the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides (Western Isles), 8 STORNOWAY sometimes along the mainland coast, but more often across beautiful and fascinating islands. This is the perfect opportunity Harris to explore all that the western Highlands and Islands of Scotland have to offer: prehistoric stone circles, burial cairns, and settlements, Gaelic culture; and remarkable wildlife—all 7 amidst dramatic land- and seascapes. Most of the tour will be off the well-beaten tourist trail through 6 some of Scotland’s most magnificent scenery. We will hike on seven islands. Sculpted by the sea, these islands have long and Skye varied coastlines, with high cliffs, sea lochs or fjords, sandy and rocky bays, caves and arches - always something new to draw 5 INVERNESSyou on around the next corner. Highlights • Tobermory, Mull; • Boat trip to and walks on the Isles of Staffa, with its basalt columns, MALLAIG and Iona with a visit to Iona Abbey; 4 • The sandy beaches on the Isle of Harris; • Boat trip and hike to Loch Coruisk on Skye; • Walk to the tidal island of Oronsay; 2 • Visit to the Standing Stones of Calanish on Lewis. 10 Staffa • Butt of Lewis hike. 3 Mull 2 1 Iona OBAN Kintyre Islay GLASGOW EDINBURGH 1. Glasgow - Isle of Mull 6. Talisker distillery, Oronsay, Iona Abbey 2. -

(Hirta) (UK) ID N° 387 Bis Background Note: St. Kilda

WORLD HERITAGE NOMINATION – IUCN TECHNICAL EVALUATION Saint Kilda (Hirta) (UK) ID N° 387 Bis Background note: St. Kilda was inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1986 under natural criteria (iii) and (iv). At the time IUCN noted that: The scenery of the St. Kilda archipelago is particularly superlative and has resulted from its volcanic origin followed by weathering and glaciation to produce a dramatic island landscape. The precipitous cliffs and sea stacks as well as its underwater scenery are concentrated in a compact group that is singularly unique. St. Kilda is one of the major sites in the North Atlantic and Europe for sea birds with over one million birds using the Island. It is particularly important for gannets, puffins and fulmars. The maritime grassland turf and the underwater habitats are also significant and an integral element of the total island setting. The feral Soay sheep are also an interesting rare breed of potential genetic resource significance. IUCN also noted: The importance of the marine element and the possibility of considering marine reserve status for the immediate feeding areas should be brought to the attention of the Government of the UK. The State Party presented a re-nomination in 2003 to: a) seek inclusion on the World Heritage List for additional natural criteria (i) and (ii), as well as cultural criteria (iii), (iv), and (v), thus re-nominating St. Kilda as a mixed site; and b) to extend the boundaries to include the marine area. _________________________________________________________________________ 1. DOCUMENTATION i) IUCN/WCMC Data Sheet: 25 references. ii) Additional Literature Consulted: Stattersfield. -

Socio Economic Update No 39 H T December 2018

s e id r b Comhairle nan Eilean Siar e H r e Development Department t u O e Socio Economic Update No 39 T December 2018 ational Records of Scotland published Life Expectancy for Administrative Areas within Scotlnad N2015-2017 in December 2018. The publication includes life expectancy estimates for council areas, NHS board areas and Scottish Parliamentary constituencies. This report shows that there has been a small decrease in life expectancy in Scotland for both females and males. emale and male life expectancy at birth has However, male life expectancy in the Outer Fincreased in all of Scotland’s council areas Hebrides continues to improve slightly. over the last ten years. However, in 2015-2017 more than half of Scotland’s council areas have Life expectancy at birth in island areas experienced a decrease or have had no change. 2015-2017 84.0 82.8 83.2 81.7 Life expectancy at birth was highest in East 82.0 81.1 79.5 80.0 Renfrewshire at 80.5 years for males and 83.7 for 78.3 78.0 76.8 77.0 females. It was lowest in Glasgow city at 73.3 Age 76.0 74.0 years for males and 78.7 years for females. 72.0 Outer Hebrides Scotland Shetland Orkney The greatest increase for males was in Orkney Males Females where it has increased by 4.2 years between 2005- 07 to 2015-17. There was an increase of 3.6 years for males in the Outer Hebrides. Life expectancy The report also looks at the probability of those at birth is now 76.8 years for males in the Outer born in Scotland in 2015 to 2017 reaching the age Hebrides in 2015-17, ranked 22 out of the 32 of 90+. -

Archaeology Development Plan for the Small Isles: Canna, Eigg, Muck

Highland Archaeology Services Ltd Archaeology Development Plan for the Small Isles: Canna, Eigg, Muck, Rùm Report No: HAS051202 Client The Small Isles Community Council Date December 2005 Archaeology Development Plan for the Small Isles December 2005 Summary This report sets out general recommendations and specific proposals for the development of archaeology on and for the Small Isles of Canna, Eigg, Muck and Rùm. It reviews the islands’ history, archaeology and current management and visitor issues, and makes recommendations. Recommendations include ¾ Improved co-ordination and communication between the islands ¾ An organisational framework and a resident project officer ¾ Policies – research, establishing baseline information, assessment of significance, promotion and protection ¾ Audience development work ¾ Specific projects - a website; a guidebook; waymarked trails suitable for different interests and abilities; a combined museum and archive; and a pioneering GPS based interpretation system ¾ Enhanced use of Gaelic Initial proposals for implementation are included, and Access and Audience Development Plans are attached as appendices. The next stage will be to agree and implement follow-up projects Vision The vision for the archaeology of the Small Isles is of a valued resource providing sustainable and growing benefits to community cohesion, identity, education, and the economy, while avoiding unnecessary damage to the archaeological resource itself or other conservation interests. Acknowledgements The idea of a Development Plan for Archaeology arose from a meeting of the Isle of Eigg Historical Society in 2004. Its development was funded and supported by the Highland Council, Lochaber Enterprise, Historic Scotland, the National Trust for Scotland, Scottish Natural Heritage, and the Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust, and much help was also received from individual islanders and others. -

279 1. Area Occupied by the .Rocks

Downloaded from http://jgslegacy.lyellcollection.org/ at University College London on June 16, 2016 1871.] GEIKIE--TERTIARYVOT.CANZC ~OeKS. 279 Sir P. •GERTON replied that there was no deficiency of pabulum for any kind of fish in the sea represented by the Lias of Lyme Regis. He also made some remarks on another somewhat similar Specimen in his own museum. The plate referred to by Dr. Giinther, he stated, was symmetrical, and not like the lateral plates on the Sturgeon, which are unsymmetrical. He therefore thought it dorsal. 2. On the T~.RTZA~Z VOLCANZC ROCKS Of the BRITISH ISLANDS. By ARC~BAT.D G~.IKIF~, Esq., F.R.S., F.G.S., Director of the Geological Survey of Scotland, and Professor of Geology in the University of Edinburgh.--First Paper. [P,,~TE XlT.] IN the present communication I propose to offer to the Society the first of a series of papers descriptive of those latest of the British volcanic rocks which intersect and overlie our Palaeozoic and Second- ary formations, and which, from fossil evidence, are to be regarded as of miocene, or at least of older Tertiary, date. Materials for this purpose have been accumulating with me for some years past. In bringing forward this first instalment of them, I wish to preface the subject with some general introductory remarks regarding the place which the rocks seem to me to hold in British geology, and on the nomenclature which I shall use in describing them. These remarks will be followed by a detailed description of the first of a succession of districts where the characteristic features of the rocks are well displayed. -

Rubha Port an T-Seilich 2017 Excavation Report

The Rubha Port an t-Seilich Project 2017 report The Rubha Port an t-Seilich Project | 2017 The archaeological significance of Rubha Port an t-Seilich is matched “ by its spectacular setting on the east coast of Islay. Having the opportunity to excavate the site is both a privilege and a responsibility. By this we can address key research questions about the human past while also giving The project works University of Reading students closely with Islay an outstanding archaeological Heritage, a Scottish experience, one that expands their Charity (SCO46938) knowledge, develops their skills devoted to furthering and builds their abilities for teamwork. knowledge about Islay’s past, and the many Steven Mithen Professor of Early Prehistory and ” ways in which it can Deputy Vice Chancellor, University of Reading, be explored and and Chair of Islay Heritage (SC046938) enjoyed by everyone [email protected] www.islayheritage.org. www.islayheritage.org 1 The Rubha Port an t-Seilich Project | 2017 The straits passing between Islay and Jura provide a major seaway used throughout history and today by sailing boats, kayaks, fishing boats and ferries. Rubha Port an t-Seilich, located close to the present day ferry terminal of Port Askaig, shows that this history of sea travel reaches far back into prehistory. 2 The Rubha Port an t-Seilich Project | 2017 Outer Hebrides The Rubha Port an t-Seilich Project Rubha Port an t-Seilich is located on the east Scotland coast of the Isle of Islay in western Scotland. A small terrace overlooks It is the only site in Scotland the Sound of Islay and is where evidence of ice age Inner Hebrides known to be the past hunter-gatherers is known camping site of prehistoric to remain largely undisturbed, hunter-gatherers between sealed below the debris from 12,000 and 7000 years ago. -

Download Trip Notes

Isle of Skye and The Small Isles - Scotland Trip Notes TRIP OVERVIEW Take part in a truly breathtaking expedition through some of the most stunning scenery in the British Isles; Scotland’s world-renowned Inner Hebrides. Basing ourselves around the Isles of Skye, Rum, Eigg and Muck and staying on board the 102-foot tall ship, the ‘Lady of Avenel’, this swimming adventure offers a unique opportunity to explore the dramatic landscapes of this picturesque corner of the world. From craggy mountain tops to spectacular volcanic features, this tour takes some of the most beautiful parts of this collection of islands, including the spectacular Cuillin Hills. Our trip sees us exploring the lochs, sounds, islands, coves and skerries of the Inner Hebrides, while also providing an opportunity to experience an abundance of local wildlife. This trip allows us to get to know the islands of the Inner Hebrides intimately, swimming in stunning lochs and enjoying wild coastal swims. We’ll journey to the islands on a more sustainable form of transport and enjoy freshly cooked meals in our downtime from our own onboard chef. From sunsets on the ships deck, to even trying your hand at crewing the Lady of Avenel, this truly is an epic expedition and an exciting opportunity for adventure swimming and sailing alike. WHO IS THIS TRIP FOR? This trip is made up largely of coastal, freshwater loch swimming, along with some crossings, including the crossing from Canna to Rum. Conditions will be challenging, yet extremely rewarding. Swimmers should have a sound understanding and experience of swimming in strong sea conditions and be capable of completing the average daily swim distance of around 4 km (split over a minimum of two swims) prior to the start of the trip. -

A Genevan's Journey to the Hebrides in 1807: an Anti-Johnsonian Venture Hans Utz

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 27 | Issue 1 Article 5 1992 A Genevan's Journey to the Hebrides in 1807: An Anti-Johnsonian Venture Hans Utz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Utz, Hans (1992) "A Genevan's Journey to the Hebrides in 1807: An Anti-Johnsonian Venture," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 27: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol27/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hans UIZ A Genevan's Journey to the Hebrides in 1807: An Anti-Johnsonian Venture The book Voyage en Ecosse et aux Iles Hebrides by Louis-Albert Necker de Saussure of Geneva is the basis for my report.! While he was studying in Edinburgh he began his private "discovery of Scotland" by recalling the links existing between the foreign country and his own: on one side, the Calvinist church and mentality had been imported from Geneva, while on the other, the topographic alternation between high mountains and low hills invited comparison with Switzerland. Necker's interest in geology first incited his second step in discovery, the exploration of the Highlands and Islands. Presently his ethnological curiosity was aroused to investigate a people who had been isolated for many centuries and who, after the abortive Jacobite Re bellion of 1745-1746, were confronted with the advanced civilization of Lowland Scotland, and of dominant England. -

Shorewatch News

Issue 16: Summer 2014 ShorewatchShorewatch News What’s inside this issue? Big Watch Weekend.....page 2/3 Wild Dolphins..............page 3 Events & News............page 4 ©WDC/ Fiona Hill ©WDC/ Walter Innes Walter ©WDC/ Hello Shorewatchers, Summer has arrived and is going by very quickly, you have all been out doing lots of watches all around the coastline and we have really enjoyed receiving all your exciting data! Spey Bay has been a hive of activity, with many sightings of the bottlenose dolphins and lots of visitors through the door! The Wild Dolphins (featured above) have been a great hit in Aberdeen - lots of people taking part in the trail. We’ve recently had some great news about the Marine Protected Areas around the Scottish Coast, largely thank- ful to all the data we have been able to present to the Scottish Government, which has come from you. So thank you for all your efforts - keep up the good work! (turn to page 4 for more info) Happy watching! Sara Pearce Supported by: A world where every whale and dolphin is safe and free Shorewatch News Big Watch Weekend Issue 16: Summer 2014 June 2014: Your efforts and sightings David Haines: 12 Carol Breckenridge watches; minke, & Colin Graham: 10 Pippa Stevens, harbour porpoise, watches; 3 minke Gordon Newman, Marie 60 common dolphin Newman, Anne Milne, & 4 orca Gillian Steel, Sara Pearce, Wendy Else, Peter Jackie Pullinger, Ron Barclay, Prince: 12 watches; 2 Murray Aitken, Ann-Paulette harbour porpoise Coats, Lorraine Macdonald & Graham Kidd: Jacky Haynes: 13 watches; 3 31 watches; -

Ownership. Opportunities for Self-Н‐Build Housing Could Be Promoted

ownership. Opportunities for self-build housing could be promoted via sales of plots. • Agricultural potential is marginal and likely to remain so for some time, particularly with the uncertainties caused by Brexit. There is scope to assist in increasing the resident population of Ulva by creating multiple holdings with residents having a mix of income sources from agriculture/crofting and other employment. • There is potential for further woodland development but this will need to be decided in the context of other land uses on Ulva and the viability of additional plantings. • There is significant scope to increase visitor numbers to the island and promote the conservation of Ulva’s natural, cultural and built heritage through community-led projects, either independently or in partnership with other bodies. • There is a range of opportunities for business development. Ardalum House could be re-opened as a hostel. A campsite and bike hire business could be developed alongside the re-opened hostel. Ulva House could be let to a private business. The community could develop additional new-build small business spaces with a particular focus on tourism-related businesses. • NWMCWC is likely to have various development roles as community landlord following a successful buyout of Ulva. They will include direct delivery of projects, working in partnership with other organisations and enabling things to be done by others (for example, by providing housing plots and/or business space). • NWMCWC should consider management and governance arrangements for its role as community landlord of Ulva that maximise input from local residents and other interested organisations. For example, via continuation of the recently established Ulva Steering Group as a sub-committee of the NWMCWC with co-opted members from Ulva, Ulva Ferry and the wider North West Mull area, along with additional representation from other community groups as appropriate. -

Marion's Garden Development Concept

Of Interest. .... Scottish names & meanings throughout Marians Garden The names of streets and building projects throughout the Marians Garden project include some that are different from those many are used to seeing. We include a guide to pronunciation and meaning in this issue. Also in.eluded are some interesting facts about Scotland, the former home of Mike and Fiona Harrison, the Marians Garden developers .. Islay, pronounced "Eye-la", is the island which Mike and Fiona Harrison lived on in Scotland. There are two possibilities for the origination of the meaning of this word. Some say it means 1-lagh, the Law Island, ( I means island and laug means law) while others believe it means an island divided in two ( I means island, and l<=:ithe means half). Port Charlotte is a village on Islay and is known to be the best preserved and most attractive of those on Isla{ It is named for the viilage's founder, Walter Frederick Campbell's mother. Port Weyms, pronounced "Port Weems" means 'River Mouth'. It is a 19th century village near Port Na Haven on south west coast of Islay. Port Na Haven, built during the 19th century, about the same time as Port Weyms, means 'bay or harbor of the River'. Cao-ila, pronounced Col-ee-la, means 'the sound of Islay'. A small village on Islay and it is also the ~ nam~ of a.well known single malt whiskey distillery. Skerrols, was the name of Mike & Fiona's old farm house on Islay. The word's definition is 'fair pastures or tine land'. -

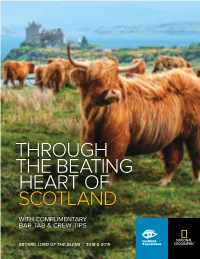

Through the Beating Heart of Scotland with Complimentary Bar Tab & Crew Tips

THROUGH THE BEATING HEART OF SCOTLAND WITH COMPLIMENTARY BAR TAB & CREW TIPS TM ABOARD LORD OF THE GLENS | 2018 & 2019 TM Lindblad Expeditions and National Geographic have joined forces to further inspire the world through expedition travel. Our collaboration in exploration, research, technology and conservation will provide extraordinary travel expe- riences and disseminate geographic knowledge around the globe. DEAR TRAVELER, The first time I boarded the 48-guest Lord of the Glens—the stately ship we’ve been sailing through Scotland since 2003—I was stunned. Frankly, I’d never been aboard a more welcoming and intimate ship that felt somehow to be a cross between a yacht and a private home. She’s extremely comfortable, with teak decks, polished wood interiors, fine contemporary regional cuisine, and exceptional personal service. And she is unique—able to traverse the Caledonian Canal, which connects the North Sea to the Atlantic Ocean via a passageway of lochs and canals, and also sail to the great islands of the Inner Hebrides. This allows us to offer something few others can—an in-depth, nine-day journey through the heart of Scotland, one that encompasses the soul of its highlands and islands. You’ll take in Loch Ness and other Scottish lakes, the storied battlefield of Culloden where Bonnie Prince Charlie’s uprising came to a disastrous end, and beautiful Glenfinnan. You’ll pass through the intricate series of locks known as Neptune’s Staircase, explore the historic Isle of Iona, and the isles of Mull, Eigg, and Skye, and see the 4,000-year-old burial chambers and standing stones of Clava Cairns.