A History of Panoramic Image Creation Adapted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Optics – Panoramic Lens Applications Revisited

Panoramic Lens Applications Revisited Simon Thibault* M.Sc., Ph.D., Eng Director, Optics Division/Principal Optical Designer ImmerVision 2020 University, Montreal, Quebec, H3A 2A5 Canada ABSTRACT During the last few years, innovative optical design strategies to generate and control image mapping have been successful in producing high-resolution digital imagers and projectors. This new generation of panoramic lenses includes catadioptric panoramic lenses, panoramic annular lenses, visible/IR fisheye lenses, anamorphic wide-angle attachments, and visible/IR panomorph lenses. Given that a wide-angle lens images a large field of view on a limited number of pixels, a systematic pixel-to-angle mapping will help the efficient use of each pixel in the field of view. In this paper, we present several modern applications of these modern types of hemispheric lenses. Recently, surveillance and security applications have been proposed and published in Security and Defence symposium. However, modern hemispheric lens can be used in many other fields. A panoramic imaging sensor contributes most to the perception of the world. Panoramic lenses are now ready to be deployed in many optical solutions. Covered applications include, but are not limited to medical imaging (endoscope, rigiscope, fiberscope…), remote sensing (pipe inspection, crime scene investigation, archeology…), multimedia (hemispheric projector, panoramic image…). Modern panoramic technologies allow simple and efficient digital image processing and the use of standard image analysis features (motion estimation, segmentation, object tracking, pattern recognition) in the complete 360o hemispheric area. Keywords: medical imaging, image analysis, immersion, omnidirectional, panoramic, panomorph, multimedia, total situation awareness, remote sensing, wide-angle 1. INTRODUCTION Photography was invented by Daguerre in 1837, and at that time the main photographic objective was that the lens should cover a wide-angle field of view with a relatively high aperture1. -

Hardware and Software for Panoramic Photography

ROVANIEMI UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED SCIENCES SCHOOL OF TECHNOLOGY Degree Programme in Information Technology Thesis HARDWARE AND SOFTWARE FOR PANORAMIC PHOTOGRAPHY Julia Benzar 2012 Supervisor: Veikko Keränen Approved _______2012__________ The thesis can be borrowed. School of Technology Abstract of Thesis Degree Programme in Information Technology _____________________________________________________________ Author Julia Benzar Year 2012 Subject of thesis Hardware and Software for Panoramic Photography Number of pages 48 In this thesis, panoramic photography was chosen as the topic of study. The primary goal of the investigation was to understand the phenomenon of pa- noramic photography and the secondary goal was to establish guidelines for its workflow. The aim was to reveal what hardware and what software is re- quired for panoramic photographs. The methodology was to explore the existing material on the topics of hard- ware and software that is implemented for producing panoramic images. La- ter, the best available hardware and different software was chosen to take the images and to test the process of stitching the images together. The ex- periment material was the result of the practical work, such the overall pro- cess and experience, gained from the process, the practical usage of hard- ware and software, as well as the images taken for stitching panorama. The main research material was the final result of stitching panoramas. The main results of the practical project work were conclusion statements of what is the best hardware and software among the options tested. The re- sults of the work can also suggest a workflow for creating panoramic images using the described hardware and software. The choice of hardware and software was limited, so there is place for further experiments. -

Download a Sample

Copyright ©2017 Hudson Henry All rights reserved. First edition, November 2017 Publisher: Rick LePage Design: Farnsworth Design Published by Complete Digital Photography Press Portland, Oregon completedigitalphotography.com All photography ©Hudson Henry Photography, unless otherwise noted. PANORAMAS MADE SIMPLE How to create beautiful panoramas with the equipment you have—even your phone By Hudson Henry Complete Digital Photography Press Portland, Oregon TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE MY PASSION FOR PANORAMAS 1 3 CAPTURING THE FRAMES 26 How is this book organized? Lens selection Exposure metering 1 AN INTRODUCTION TO PANORAMIC PHOTOGRAPHY 5 Use a tripod, Where Possible Go wide and with more detail The importance of being level Simple Panoramas Defined Orient your camera vertically Not all panoramas are narrow slices (most of the time) Equipment for simple panoramas Focus using live view Advanced panoramas Beware of polarizers or graduated filters Marking your panoramas 2 THINKING ABOUT LIGHT, FOCUS AND SETUP 12 Compose wide and use lots of overlap Light and composition: the rules still apply Move quickly and carefully Watch out for parallax Finding the infinity distance 4 ASSEMBLING YOUR PANORAMA 35 Learning how to lock your camera settings My workflow at a glance Why shouldn’t I use my phone’s Building Panoramas with automatic panorama mode? Lightroom Classic CC Why is manual exposure so important? Working with Photoshop CC to create panoramas Building Panoramas in ON1 Photo Raw 2018 5 RESOURCES 52 PREFACE MY PASSION FOR PANORAMAS My frst panorama, I GREW UP WITH ADVENTURESOME EXTENDED FAM- with image quality. Like many similar photographers, I created from three ILY MEMBERS WHO LOVED TRAVELING, CLIMBING, AND shifted to medium-format film for the bigger frame and frames of medium- format flm. -

Panorama Photography by Andrew Mcdonald

Panorama Photography by Andrew McDonald Crater Lake - Andrew McDonald (10520 x 3736 - 39.3MP) What is a Panorama? A panorama is any wide-angle view or representation of a physical space, whether in painting, drawing, photography, film/video, or a three-dimensional model. Downtown Kansas City, MO – Andrew McDonald (16614 x 4195 - 69.6MP) How do I make a panorama? Cropping of normal image (4256 x 2832 - 12.0MP) Union Pacific 3985-Andrew McDonald (4256 x 1583 - 6.7MP) • Some Cameras have had this built in • APS Cameras had a setting that would indicate to the printer that the image should be printed as a panorama and would mask the screen off. Some 35mm P&S cameras would show a mask to help with composition. • Advantages • No special equipment or technique required • Best (only?) option for scenes with lots of movement • Disadvantages • Reduction in resolution since you are cutting away portions of the image • Depending on resolution may only be adequate for web or smaller prints How do I make a panorama? Multiple Image Stitching + + = • Digital cameras do this automatically or assist Snake River Overlook – Andrew McDonald (7086 x 2833 - 20.0MP) • Some newer cameras do this by “sweeping the camera” across the scene while holding the shutter button. Images are stitched in-camera. • Other cameras show the left or right edge of prior image to help with composition of next image. Stitching may be done in-camera or multiple images are created. • Advantages • Resolution can be very high by using telephoto lenses to take smaller slices of the scene -

Ground-Based Photographic Monitoring

United States Department of Agriculture Ground-Based Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station Photographic General Technical Report PNW-GTR-503 Monitoring May 2001 Frederick C. Hall Author Frederick C. Hall is senior plant ecologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Region, Natural Resources, P.O. Box 3623, Portland, Oregon 97208-3623. Paper prepared in cooperation with the Pacific Northwest Region. Abstract Hall, Frederick C. 2001 Ground-based photographic monitoring. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-503. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 340 p. Land management professionals (foresters, wildlife biologists, range managers, and land managers such as ranchers and forest land owners) often have need to evaluate their management activities. Photographic monitoring is a fast, simple, and effective way to determine if changes made to an area have been successful. Ground-based photo monitoring means using photographs taken at a specific site to monitor conditions or change. It may be divided into two systems: (1) comparison photos, whereby a photograph is used to compare a known condition with field conditions to estimate some parameter of the field condition; and (2) repeat photo- graphs, whereby several pictures are taken of the same tract of ground over time to detect change. Comparison systems deal with fuel loading, herbage utilization, and public reaction to scenery. Repeat photography is discussed in relation to land- scape, remote, and site-specific systems. Critical attributes of repeat photography are (1) maps to find the sampling location and of the photo monitoring layout; (2) documentation of the monitoring system to include purpose, camera and film, w e a t h e r, season, sampling technique, and equipment; and (3) precise replication of photographs. -

Panoramic Photography & ANRA's Water Quality Monitoring Program

Panoramic Photography in ANRA’s Water Quality Monitoring Program Jeremiah Poling Information Systems Coordinator, ANRA Disclaimer The equipment and software referred to in this presentation are identified for informational purposes only. Identification of specific products does not imply recommendation of or endorsement by the Angelina and Neches River Authority, nor does it imply that the products so identified are necessarily the best available for the purpose. All information presented regarding equipment and software, including specifications and photographs, were acquired from publicly-available sources. Background • As part of our routine monitoring activities, standard practice has been to take photographs of the areas upstream and downstream of the monitoring station. • Beginning in the second quarter of FY 2011, we began creating panoramic images at our monitoring stations. • The panoramic images have a 360o field of view and can be viewed interactively in a web browser. • Initially these panoramas were captured using a smartphone. • Currently we’re using a digital SLR camera, fisheye lens, specialized rotating tripod mount, and a professional software suite to create and publish the panoramas. Basic Terminology • Field of View (FOV), Zenith, Nadir – When we talk about panoramas, we use the term Field of View to describe how much of the scene we can capture. – FOV is described as two numbers; a Horizontal FOV and a Vertical FOV. – To help visualize what the numbers represent, imagine standing directly in the center of a sphere, looking at the inside surface. • We recognize 180 degrees of surface from the highest point (the Zenith) to the lowest point (the Nadir). 180 degrees is the Maximum Vertical FOV. -

Photography Techniques Intermediate Skills

Photography Techniques Intermediate Skills PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Wed, 21 Aug 2013 16:20:56 UTC Contents Articles Bokeh 1 Macro photography 5 Fill flash 12 Light painting 12 Panning (camera) 15 Star trail 17 Time-lapse photography 19 Panoramic photography 27 Cross processing 33 Tilted plane focus 34 Harris shutter 37 References Article Sources and Contributors 38 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 39 Article Licenses License 41 Bokeh 1 Bokeh In photography, bokeh (Originally /ˈboʊkɛ/,[1] /ˈboʊkeɪ/ BOH-kay — [] also sometimes heard as /ˈboʊkə/ BOH-kə, Japanese: [boke]) is the blur,[2][3] or the aesthetic quality of the blur,[][4][5] in out-of-focus areas of an image. Bokeh has been defined as "the way the lens renders out-of-focus points of light".[6] However, differences in lens aberrations and aperture shape cause some lens designs to blur the image in a way that is pleasing to the eye, while others produce blurring that is unpleasant or distracting—"good" and "bad" bokeh, respectively.[2] Bokeh occurs for parts of the scene that lie outside the Coarse bokeh on a photo shot with an 85 mm lens and 70 mm entrance pupil diameter, which depth of field. Photographers sometimes deliberately use a shallow corresponds to f/1.2 focus technique to create images with prominent out-of-focus regions. Bokeh is often most visible around small background highlights, such as specular reflections and light sources, which is why it is often associated with such areas.[2] However, bokeh is not limited to highlights; blur occurs in all out-of-focus regions of the image. -

A Practical Guide to Panoramic Multispectral Imaging

A PRACTICAL GUIDE TO PANORAMIC MULTISPECTRAL IMAGING By Antonino Cosentino 66 PANORAMIC MULTISPECTRAL IMAGING Panoramic Multispectral Imaging is a fast and mobile methodology to perform high resolution imaging (up to about 25 pixel/mm) with budget equipment and it is targeted to institutions or private professionals that cannot invest in costly dedicated equipment and/or need a mobile and lightweight setup. This method is based on panoramic photography that uses a panoramic head to precisely rotate a camera and shoot a sequence of images around the entrance pupil of the lens, eliminating parallax error. The proposed system is made of consumer level panoramic photography tools and can accommodate any imaging device, such as a modified digital camera, an InGaAs camera for infrared reflectography and a thermal camera for examination of historical architecture. Introduction as thermal cameras for diagnostics of historical architecture. This article focuses on paintings, This paper describes a fast and mobile methodo‐ but the method remains valid for the documenta‐ logy to perform high resolution multispectral tion of any 2D object such as prints and drawings. imaging with budget equipment. This method Panoramic photography consists of taking a can be appreciated by institutions or private series of photo of a scene with a precise rotating professionals that cannot invest in more costly head and then using special software to align dedicated equipment and/or need a mobile and seamlessly stitch those images into one (lightweight) and fast setup. There are already panorama. excellent medium and large format infrared (IR) modified digital cameras on the market, as well as scanners for high resolution Infrared Reflec‐ Multispectral Imaging with a Digital Camera tography, but both are expensive. -

Panorama Time

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in . Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Simbelis, V. (2017) Time and Space in Panoramic Photography Acoustic Space, 16(4): 233-245 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:kth:diva-224616 -RENEWABLE FUTURES- Time and Space in Panoramic Photography Vygandas “Vegas” Šimbelis KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden Abstract This article intends to show a usage-hacking case of everyday technology for creating visual narratives. The photographic art project “Panorama Time” is discussed through a techno-cultural perspective and examines the spatial-temporal dimension in panoramic photography, which, in this case, is a digital camera in a mobile phone. The post-media condition and its characteristic of embracing the fusion of different media in one device without specifying any single one is examined in our project through the combination of photographic and cinematographic processes combined in the mobile device. The rolling shutter feature, which is the technological core of digital cameras, enables the strip-photography technique, in our case used in a panoramic technique to deliver a set of concepts: glitch, repetition, frozen frames, and similar. Through deliberate navigation and control, the user breaks the panoramic view, and thus the project’s technique presents the distinction between fault and glitch aesthetics. We show examples and demonstrate the process of creating our digital photography art project “Panorama Time”. -

Image Geometry of Vertical & Oblique Panoramic Photography

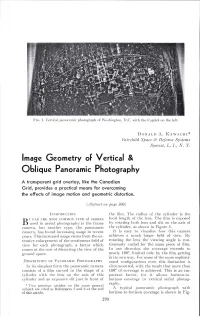

FIG. 1. Vertical panoramic photograph of Washington, D.C. with the Capitol on the left. DONALD A. KAWACHI* Fairchild Space & Defense Systems Syosset, L. I., N. Y. Image Geometry of Vertical & Oblique Panoramic Photography A transparent grid overlay, like the Canadian Grid, provides a practical means for overcoming the effects of image motion and geometric distortion. (Abstract on page 300) INTRODUCTION the fil m. The radius of the cylinder is the y FAR THE MOST COMMON TYPE of camera focal length of the lens. The fil m is exposed B used in aerial photography is the frame by rotating both lens and slit on the axis of camera, but another type, the panoramic the cylinder, as shown in Figure 3. camera, has found increasing usage in recent I t is easy to visualize how this camera years. This increased usage stems from the ex achieves a much larger field of view. By tensive enlargement of the continuous field of rotating the lens the viewing angle is con view for each photograph, a factor which tinuously varied for the same piece of film. comes at the cost of distorting the view of the In one direction the coverage extends to ground space. nearly 180°, limited only by the film getting in its own way. For some of the more sophisti DESCRIPTION OF PANORAMIC PHOTOGRAPHY cated configurations even this limitation is In its simplest form the panoramic camera circumvented, with the result that more than consists of a film curved in the shape of a 180° of coverage is achieved. This is an im cylinder with the lens on the axis of this portant factor, for it allows horizon-to cylinder and an exposure slit just in front of horizon coverage in vertical aerial photog raphy. -

Panoramas Made Simple How to Create Beautiful Panoramas with the Equipment You Have—Even Your Phone Hudson Henry

PANORAMAS MADE SIMPLE HOW TO CREATE BEAUTIFUL PANORAMAS WITH THE EQUIPMENT YOU HAVE—EVEN YOUR PHONE HUDSON HENRY PANORAMAS MADE SIMPLE How to create beautiful panoramas with the equipment you have—even your phone By Hudson Henry Complete Digital Photography Press Portland, Oregon Copyright ©2017 Hudson Henry All rights reserved. First edition, November 2017 Publisher: Rick LePage Design: Farnsworth Design Published by Complete Digital Photography Press Portland, Oregon completedigitalphotography.com All photography ©Hudson Henry Photography, unless otherwise noted. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE MY PASSION FOR PANORAMAS 1 3 CAPTURING THE FRAMES 26 How is this book organized? Lens selection Exposure metering AN INTRODUCTION TO PANORAMIC PHOTOGRAPHY 1 5 Use a tripod Go wide and with more detail The importance of being level Simple panoramas defined Orient your camera Not all panoramas are narrow slices Focus using live view Equipment for simple panoramas Beware of polarizers or graduated filters Advanced panoramas Marking your panoramas Compose wide and use lots of overlap 2 THINKING ABOUT LIGHT, FOCUS AND SETUP 12 Move quickly and carefully Light and composition: the rules still apply Watch out for parallax 4 ASSEMBLING YOUR PANORAMA 35 Finding the infinity distance My workflow at a glance Learning how to lock your camera settings Building panoramas with Lightroom Classic CC Why shouldn’t I use my phone’s automatic panorama mode? Working with Photoshop CC to create panoramas Why is manual exposure so important? Building panoramas in ON1 Photo RAW 2018 5 RESOURCES 52 Links PREFACE MY PASSION FOR PANORAMAS My first panorama, I GREW UP WITH ADVENTURESOME EXTENDED FAM- with image quality. -

DAO Level 2 Award in Surveillance Photography QN

Qualification Handbook DAO Level 2 Award in Surveillance Photography QN: 603/3192/6 The Qualification Overall Objective for the Qualifications This handbook relates to the following qualification: DAO Level 2 Award in Surveillance Photography This Level 2 Award provides the standards that must be achieved by individuals that are working within the Armed Forces. Pre-entry Requirements Entry requirements are published annually in the Defence Instructions and Notices (DIN) Joint Intelligence Training Group (JITG) Courses for Current Training Year, Course Schedule and Application Forms. Learners who are taking this qualification should be employed in a photographic surveillance role within the Armed Forces. Unit Content and Rules of Combination This qualification is made up of a total of two mandatory units and no Optional units. To be awarded this qualification the candidate must achieve a total of four credits as shown in the table below. URN Unit of assessment Level Credit GLH TQT value F/617/0047 Image capture using a Digital camera 2 1 9 10 Camera surveillance in support of Military L/617/0049 2 3 10 30 operations Total 4 19 40 Age Restriction This qualification is available to learners aged 16-18 years and 19+. Opportunities for Progression This qualification creates a number of opportunities for progression through career development and promotion. Military personnel may apply for transfer to the RN Photo Branch, Army Royal Logistics Corps (RLC) Photographer or RAF Photographer trades against established trade requirements. Exemption No exemptions have been identified. Credit Transfer Credits from similar regulated units which have already been achieved by the learner may be transferred.