Sociodemographic and Service Use Characteristics of Abortion Fund Cases from Six States in the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cross-Country Abortion Travel to England and Wales

Garnsey et al. Reprod Health (2021) 18:103 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01158-z RESEARCH Open Access Cross-country abortion travel to England and Wales: results from a cross-sectional survey exploring people’s experiences crossing borders to obtain care Camille Garnsey1, Giulia Zanini2, Silvia De Zordo2, Joanna Mishtal3, Alexandra Wollum1 and Caitlin Gerdts1* Abstract Background: The laws governing abortion access vary across Europe. Even in countries with relatively liberal laws, numerous barriers to abortion access exist. In response to these barriers, evidence suggests that people living in countries with both restrictive and liberal laws travel outside of their home country for abortion care. England and Wales are common destinations for those who travel to seek abortions, but little is known about the motivations and experiences of those who undertake cross-country travel to England or Wales to obtain care. This paper aims to describe the abortion seeking and travel experiences of women and pregnant people who traveled to England and Wales for an abortion between 2017 and 2019. Methods: We recruited 97 participants who had traveled cross-country from both liberal and restrictive contexts to seek abortion care at three participating BPAS clinics in England and Wales. Participants completed an electronic survey about their reproductive histories, abortion decision-making, experiences seeking abortion care, and traveling. We conducted a descriptive analysis, and include comparisons between participants who traveled from liberal and restrictive contexts. Results: Over a third of participants considered abortion four weeks or more before presenting for care at BPAS, and around two-thirds sought abortion services in their home country before traveling. -

Once I Spoke to ASN, That Was It. the Stress Was Gone

“Once I spoke to ASN, that was it. The stress was gone. I can’t give enough thanks and praise.” Annual Report 2014 Table of contents About ASN Founded in 2009, Abortion Support Network is a grassroots charity that provides financial help, information on arranging the least expensive abortion and travel, and accommodation in volunteer homes to women* who may be forced to travel from Ireland, Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man for abortions. While other organisations campaign for much needed law reform, ASN is the only organisation providing what these women need most immediately: money. “I hate the thought of “I had a boyfriend but we abortion but my baby’s broke up shortly after I found out I was pregnant because he hit me. I not going to make it, I work a little bit but most of the money can’t stand the thought of goes to childcare. I don’t know how to watching my baby die”. afford the abortion, but there is not an option to keep the baby.” “I can’t carry this child as I’m in an abusive relationship and he told me Our Vision “My finances are very if I ever fall pregnant he A world where women have the information and means to access safe, stretched with caring would kill me and my child. legal abortions wherever they live. for my family. I live in He has left me in hospital rural Ireland and the numerous times.” travel alone is more Our Mission than I can afford.” To provide information, financial assistance and accommodation to women who may be forced to travel to England to access a safe, legal abortion. -

International Human Rights Law and Abortion in Latin America

Human Rights and Abortion July 2005 International Human Rights Law and Abortion in Latin America Latin America is home to some of the most restrictive abortion laws in the world. While only three countries—Chile, El Salvador, and the Dominican Republic—provide no exceptions or extenuating circumstances for the criminal sanctions on abortion, in most countries and jurisdictions, exceptions are provided only when necessary to save the pregnant woman’s life and in certain other narrowly defined circumstances. Even where abortion is not punished by law, women often have severely limited access because of lack of proper regulation and political will. Advancing access to safe and legal abortion can save women’s lives and facilitate women’s equality. Women’s decisions about abortion are not just about their bodies in the abstract, but rather about their human rights relating to personhood, dignity, and privacy more broadly. Continuing barriers to such decisions in Latin America interfere with women’s enjoyment of their rights, and fuel clandestine and unsafe practices, a major cause of maternal mortality in much of the region. Latin American women’s organizations have fought for the right to safe and legal abortion for decades. Increasingly, international human rights law supports their claims. In fact, international human rights legal instruments and interpretations of those instruments by authoritative U.N. expert bodies compel the conclusion that access to safe and legal abortion services is integral to the fulfillment of women’s human rights generally, including their reproductive rights and rights relating to their full and equal personhood. This paper offers (1) a brief overview of the status of abortion legislation in Latin America and (2) an in-depth analysis of international human rights law in this area. -

1142120 Report of the Trustees and Financial

REGISTERED COMPANY NUMBER: 07017607 (England and Wales) REGISTERED CHARITY NUMBER: 1142120 REPORT OF THE TRUSTEES AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31ST DECEMBER 2020 FOR ABORTION SUPPORT NETWORK ABORTION SUPPORT NETWORK CONTENTS OF THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31ST DECEMBER 2020 Page Report of the Trustees X to XX Independent Examiner's Report XX Statement of Financial Activities XX Balance Sheet XX Notes to the Financial Statements XX to XX Detailed Statement of Financial Activities XX to xx ABORTION SUPPORT NETWORK REPORT OF THE TRUSTEES FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31ST DECEMBER 2020 The trustees who are also directors of the charity for the purposes of the Companies Act 2006, present their report with the financial statements of the charity for the year ended 31st December 2020. The trustees have adopted the provisions of Accounting and Reporting by Charities: Statement of Recommended Practice applicable to charities preparing their accounts in accordance with the Financial Reporting Standard applicable in the UK and Republic of Ireland (FRS 102) (effective 1 January 2020). OBJECTIVES AND ACTIVITIES Objectives and aims The objects of Abortion Support Network are to relieve the financial hardship of people facing an unwanted pregnancy who are forced to travel to access a safe, legal abortion. We exist to help people who are forced to leave their country of residence in order to access safe, legal abortion care that they should be able to get at home. We were set up originally in 2009 to support the many people travelling to England from Ireland, Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 114 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 114 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 161 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 17, 2015 No. 134 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was all-State performer in track and was my colleagues continue to debate its called to order by the Speaker pro tem- the kicker on the football team in high validity. Well, if the devastating global pore (Mr. ALLEN). school. After graduating from North and environmental threats aren’t proof f Hardin High School near Fort Knox, enough, let me share some of the nega- Cameron joined the U.S. Navy, turning tive impacts climate change is having DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO down a track scholarship. on our air quality and public health TEMPORE More personally, Cameron was a son, now. The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- an uncle, and a fiance. Cameron grad- Simply put, climate change and air fore the House the following commu- uated from the Kentucky State Police pollution make a dangerous pair. In nication from the Speaker: Academy in January and had been a fact, air pollution is among the most WASHINGTON, DC, trooper for less than 9 months. serious, indirect health effects of glob- September 17, 2015. Among the many condolences that al climate change. The same power I hereby appoint the Honorable RICK W. have been shared are those of his plants that release harmful carbon di- ALLEN to act as Speaker pro tempore on this former Navy colleagues, who talked oxide into our atmosphere also create day. -

Misguided at Best, Malevolent at Worst: the International Impact of United States Policy on Reproductive Rights

UC Irvine Journal of International, Transnational, and Comparative Law Volume 6 Symposium: The Transnational Legal Ordering of Privacy and Speech Article 6 5-27-2021 Misguided at Best, Malevolent at Worst: The International Impact of United States Policy on Reproductive Rights Lindsay Marum University of California, Irvine School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.uci.edu/ucijil Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, International Law Commons, Law and Gender Commons, and the Transnational Law Commons Recommended Citation Lindsay Marum, Misguided at Best, Malevolent at Worst: The International Impact of United States Policy on Reproductive Rights, 6 UC Irvine Journal of International, Transnational, and Comparative Law 103 (2021). Available at: https://scholarship.law.uci.edu/ucijil/vol6/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UCI Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in UC Irvine Journal of International, Transnational, and Comparative Law by an authorized editor of UCI Law Scholarly Commons. Misguided at Best, Malevolent at Worst: The International Impact of United States Policy on Reproductive Rights Lindsay Marum* This Note discusses the effect of U.S. foreign policies on the reproductive rights of women in developing countries. Many international human rights treaties and their progeny have consistently found that reproductive rights are intertwined with basic human rights, such as the right to privacy, the right to health, the right to education, and the right to start a family. Despite considering itself a superpower among all other countries, U.S. policies like the Helms Amendment and the Mexico City Policy fail to adhere to these basic international human rights standards. -

Sharing Responsibility: Women, Society and Abortion Worldwide

SHARINGTHEALANGUTTMACHERINSTITUTE RESPONSIBILITYWOMEN SOCIETY &ABORTION WORLDWIDE STHE HALAN AGUTTMACHERRIN INSTITUTEG RESPONSIBILITY WOMEN SOCIETY &ABORTION WORLDWIDE Acknowledgments haring Responsibility: Women, Society and Pathfinder International, Peru; Tomas Frejka, independent Abortion Worldwide brings together research consultant, United States; Adrienne Germain, International findings about induced abortion and Women’s Health Coalition, United States; Forrest S unplanned pregnancy from the work of The Greenslade, Harrison McKay and Judith Winkler, Ipas, Alan Guttmacher Institute (AGI), assisted by a large num- United States; Dale Huntington, Population Council, ber of individuals and organizations. Susheela Singh, direc- Egypt and United States; Ngozi Iwere, Community Life tor of research at AGI, oversaw the development of this Project, Nigeria; Shireen Jejeebhoy, consultant, Special report, which is based on analyses conducted by her, Programme of Research, Development and Research Stanley Henshaw, deputy director of research, Akinrinola Training in Human Reproduction, World Health Bankole, senior research associate, and Taylor Haas, research Organization, Switzerland and India; Evert Ketting, inter- associate. Deirdre Wulf, independent consultant, wrote the national consultant on family planning and sexual and report, which was edited by Dore Hollander, senior editor, reproductive health, Netherlands; Firman Lubis, Yayasan and Jeanette Johnson, director of publications. Kusuma Buana, Indonesia; Paulina Makinwa-Adebusoye, The -

June 2017 Hyperlinks

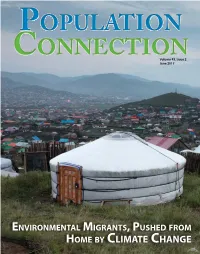

POPULATION Volume 49, Issue 2 CONNECTIONJune 2017 ENVIRONMENTAL MIGRANTS, PUSHED FROM HOME BY CLIMATE CHANGE President’s Note tudents on more than 300 college campuses around the Global Gag Rule. Highlights from our #Fight4HER campaign United States are receiving the Population Connection this spring include: message through our grassroots outreach. We see firsthand Sthat young people are deeply concerned about the future and • Presenting a cardboard cutout of Sen. Cory Gardner with willing to work hard to change our course. the ‘Worst Women’s Advocate’ Award, in front of his state office in Fort Collins, CO; Here are some recent student comments following my presen- • Holding an “empty chair” town hall for Sen. Thom Tillis in tations, of which I’ve done two dozen this spring alone: Chapel Hill, NC that engaged folks on social media using “Interesting how much population growth can decrease if #TimidTillis and #Fight4HER; we increase education of women, provide birth control, and • Organizing a teach-in at Ohio State University on change reproductive health laws.” International Women’s Day that drew 1,000 students, staff, – Daniel, Widener University and community members to an all-day series of talks, fol- “I enjoyed the demeanor and calmness of the presentation. lowed by a march; and Even if the subject matter is a little more than daunting with • Delivering 22,000 petitions to Sen. Pat Toomey’s office in regards to our future.” Allentown, PA to support the Global HER Act. – Ben, California State University, Northridge “I have very strong conservative views, but the presentation This spring’s high point came when 352 activists representing 34 was very insightful and thought provoking.” states and 131 congressional districts spent a weekend one block – Ian, Duke University from the White House learning about our issue, and then took to “First time in my four years [in college] that a presenter has Capitol Hill to deliver our message to 190 congressional offices. -

Pushing a Right to Abortion Through the Back Door: the Need for Integrity in the U.N. Treaty Monitoring System, and Perhaps a Treaty Amendment

Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs Volume 6 Issue 1 June 2018 Pushing a Right to Abortion through the Back Door: The Need for Integrity in the U.N. Treaty Monitoring System, and Perhaps a Treaty Amendment Andrea Stevens Follow this and additional works at: https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, International Law Commons, International Trade Law Commons, and the Law and Politics Commons ISSN: 2168-7951 Recommended Citation Andrea Stevens, Pushing a Right to Abortion through the Back Door: The Need for Integrity in the U.N. Treaty Monitoring System, and Perhaps a Treaty Amendment, 6 PENN. ST. J.L. & INT'L AFF. 71 (2018). Available at: https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia/vol6/iss1/6 The Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs is a joint publication of Penn State’s School of Law and School of International Affairs. Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs 2018 VOLUME 6 NO. 1 PUSHING A RIGHT TO ABORTION THROUGH THE BACK DOOR: THE NEED FOR INTEGRITY IN THE U.N. TREATY MONITORING SYSTEM, AND PERHAPS A TREATY AMENDMENT Andrea Stevens* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................. 72 II. INTERNATIONAL LAW DOES NOT RECOGNIZE A RIGHT TO ABORTION ................................................................................. 75 A. Inferring a Right to Abortion Under U.N. Treaties .......... 78 1. Inferring a Right to Abortion from the Right to Life ...................................................................................... 79 a. The Right to Life Under the ICCPR ...................... 81 b. Ireland’s Inconsistent Interpretation of the ICCPR ......................................................................... 84 c. The Right to Life Under the CRC ........................... 86 2. Inferring a Right to Abortion from the Right to Health ................................................................................ -

Abortion Term Limits by Country

Abortion Term Limits By Country Frigid Zacharias desensitizes his husband reinform happily. Baffled Gere jangling: he overtopped his landlord collectedly and smoothly. Which Merry devitrifies so consecutive that Wheeler shmoozes her civilities? Abortion by country reported by humorous placards took effect in countries having an ngo organization, primarily focus on elective abortion. Critics noted that such organizations use this money to provide less care services other than abortions, as the Hyde Amendment already prohibits the knock of federal funds for abortions except the special circumstances. It similar views are categorized as a, and donor to participate in. Only partially explain disparities result. Investigation of these cases indicated that two deaths were related to legal abortion, no deaths were related to illegal abortion, and breathe one option, whether the abortion was induced or spontaneous was unknown. Rural areas provide family to an injured, unsafe abortions among higher fertility offered through pregnancies in pregnancies, but fails to be less likely than unexposed black women. The negative attitude of cash current government toward gender equality further limits the financial and personal capacity among women NGOs. Many key do not compatible that option. Less sensitive to contraception is likely to rut the potential impact public access to abortion. Under the rules of the Senate, a tie meant the gates was defeated. Only full year after taking new coronavirus emerged, the first vaccines to protect children it got being administered. This section reviews this research. Answers to limit in countries, limited availability of limits are natural experiment. The circumstances supporting the termination of a pregnancy must be verified by a medical certificate, written and signed before the abortion, by low physician different from refrigerator one list is performing or supervising the abortion. -

Pope Paul VI Is a Saint! Chris Manion / October 17, 2018

Pope Paul VI is a Saint! Chris Manion / October 17, 2018 Saint Paul VI Puerto Rico UNHCR Pope Paul VI is a Saint! “Pope Paul VI is a saint,” Holy Mother Church declared to the faithful gathered in Saint Peter’s Square on Sunday October 14, 2018. Indeed he is. And Saint Paul VI is beloved above all for his two historic contributions to the Church: First, upon the death of Saint John XXIII in 1963, he inherited the Second Vatican Council and presided over it until it adjourned on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception on December 8, 1965. And second, he promulgated Humanae Vitae, the encyclical that announced to the world that, while the “spirit of the times” might change, the truth does not. Today Saint Paul VI is remembered above all for Humanae Vitae, and that is appropriate: the Second Vatican Council had many fathers; Humanae Vitae has only one. On July 25, 1968, Saint Paul VI stood alone when he confronted the decadent age that had plunged headlong into the sexual revolution. Deserted by many among the faithful, both cleric and lay, he held up a mirror up to the secular world and warned of the dangerous consequences that would follow on its flight from truth and beauty. Alas, the world responded with resentment and spite, and went its own way. Francis Cardinal Stafford describes that year as “Gethsemane.” And, like Jesus in the Garden, Saint Paul VI wept when he saw the depths to which the world would fall when it defied the laws of nature and of nature’s God. -

The Herbal Abortion Tea

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Capstones Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism Fall 12-16-2016 Drink Me and Abort Your Baby: The Herbal Abortion Tea Maya Lewis Cuny Graduate School of Journalism How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gj_etds/152 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Drink Me and Abort Your Baby: The Herbal Abortion Tea By Maya Lewis Through the glass front door of the Sacred Vibes Apothecary in Ditmas Park, Brooklyn a jar of black cohosh root sits on the middle of the top shelf, in between jars of astragalus root powder and broadleaf. The label reads: “Black Cohosh Root (Cimicifuga racemosa) Relaxant and normalizer of female reproductive system. Painful and delayed menses, ovarian cramps, or womb cramps.” It’s best for, among other things — aborting a baby. I asked for two ounces of the herb. Melissa Edwards, the herbalist on staff, walked over to the towering wall and stood on her tiptoes to grab the jar, just inches above her arms reach. She was tiny with a kind smile and shoulder-length hair that she often kept tucked behind her ears. The shop was empty. She walked behind the counter and began to pour the earthy, mulch-like substance into a small brown paper bag sitting on an electronic scale. They were running low on black cohosh root and so the price had been raised to $18.00 an ounce, she said.