Twelve Month Crush

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

David Humphrey

DAVID HUMPHREY Lives and works in New York 1956-73 Grows up in Pittsburgh, PA 1973-77 Attends Maryland Institute College of Art, Baltimore, Receives BFA 1976-77 Studies at New York Studio School of Painting, Drawing, and Sculpture 1977-80 Attends New York University, New York, Receives MA 1979-80 Receives New York State CAPS grant 1985 Receives New York State Council for the Arts Grant 1987 Receives fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts 1995 Receives fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts 2002 Receives fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Receives the Thomas B. Clarke prize from the National Academy of Design 2008 Rome Prize, American Academy in Rome SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2010 Solomon Projects, Atlanta Derfrosted, in collaboration with Adam Cvijanovic, Postmasters, NY 2008 Keith Talent Gallery, London Parisian Laundry, Montreal 2007 Amaya Gallery, Miami, FL 2006 Solomon Projects, Atlanta, GA Fredric Snitzer Gallery, Miami FL Snowman in Love, Triple Candie, NY Team ShaG, I Space, Chicago 2005 Next of Kin, Rebecca Ibel Gallery, Columbus, OH Oven Stuffer Roaster, Morsel, NY 2004 Brent Sikkema, New York, NY 2002 Both Less and More, paintings and sculpture, Littlejohn Contemporary, NY Holiday Melt, Solomon Projects, Atlanta, GA *Lace, Bubbles, Milk, digital Works Pittsburgh Filmmakers, Pittsburgh, PA Fredric Snitzer Gallery, Miami FL 2001 University of Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara CA Holiday Melt, Saks Project Art holiday windows, Palm Beech FL 2000 Mckee Gallery, New York, NY 1999 Sculptures, Deven GoldenFine Art, LTD, New York, NY Me and My Friends, The Phillip Feldman Gallery, Pacific Northwest College of Art, Portland, OR 1998 Zolla/Lieberman Gallery, Chicago, IL Works on Paper, Roy G Biv Gallery, Columbus OH 1997 SHaG, team paintings by A. -

David Humphrey Arms of the Law November 12 Through December 19, 2020

David Humphrey Arms of the Law November 12 through December 19, 2020 Fredericks & Freiser is pleased to present an exhibition of new paintings by David Humphrey. Arms of the Law takes the police as its principal subject. Originally inspired by images seen on the television show Body Cam the work has expanded to embrace a variety of points of view, including confrontations between protesters and armed law enforcement officers. Humphrey applies his wide-ranging genre-mixing (abstraction, pop-surrealism and photo-derived representation) to the paradoxical challenge of making works with authority and power committed to questioning authority and power. Authority’s gesture, the task of the violence worker (police), is to neutralize agency, to stop a person in their tracks; to arrest their ability to move. The cop’s task is to produce and distribute violence in the name of order; but the disorder that results often serves authority’s purpose just as well by “proving” the necessity for increased state violence. What kind of power can a painted image have? Like the police, a painting arrests motion, but in the service of poetic freedom. The application of an abstracting, formalized artifice can produce both a reflective distance for the viewer and an intense embodied presence that challenges detachment. A space is provided for sustained associative regard and a charged urgency. Some of these works fuse militarized police with neutralized citizens into a monstrous hybrid, a dynamic liquid whole in a space littered with trash and painterly affect. This show continues Humphrey’s forty-year commitment to making formally inventive, psycho- socially engaged paintings and sculpture and is accompanied by a 290 page monograph by Davy Lauterbach, with additional texts by Lytle Shaw, Wayne Koestenbaum, Humphrey himself and an interview with Jennifer Coates (published by Fredericks & Freiser and distributed by D.A.P). -

Curriculum Vitae

11-22 44th Rd Long Island City, NY www.false-flag.org [email protected] VIRGINIA LEE MONTGOMERY Born in Houston, TX and lives in TX Work s between T X and NY , USA EDUCATION 2016 Yale Universit y, Scul pture, MFA 2008 The Univ ersity of Texas at Aust in, BFA EXHIBITIO NS 2020 DREAM C OCOON, Hesse Flato w, New York, NY — SOLO up c om ing After Carolee, Curat or Anne tte DiMeo Carloz zi, Art pa ce , San Antonio, TX upcoming WITCH HUN T, Curato rs Alison Kar asyk & Jeppe Ugel vig, Kunsth al Charlottenborg, Copenhagen, Denmark upcoming Exquis ite Corp se of the Surrea l: Bring Your Own Beam er, Cu rator Mary Magsamen, Menil Collection, Houston, TX upcoming In Union, Re motely, The Sha ke r Museum, Mount Leb anon, N Y — upcoming VLM: SK Y LOOP , Lawndale Art Cente r, Houst on, TX — SOLO Oxford Film Festiv al, Expe rim ental Short Films, 2019, O xford, MI Virtual D ream Cen ter: P reC og Screening, Queens Muse um, Queens, NY BAIT BALL, Curated by Like A Little Disaster Gallery, Palazzo Sa n Giuseppe, Polignano a Mare, Italy 2019 HONEY MOON , Mi d night Mom ent at Times S quare, Times S quare A rt Alliance, New York, NY — SOLO PONY COC OON, False F lag Projects, Queens, NY — SOLO Screen Series: V irginia Le e Mont gomery , Curator Ka te W iener, New Museum, New York, NY — SOLO THE PONY HO TEL: VLM & Geor ge Minne, Mus eum Folk wang, Essen, Germany — SOLO An unb ound knot in the wind, Curator Alison Karasyk, Berrie Center, Ramapo, Mahwah, NJ CYFE ST12 Internati ona l: Perso nal Ident ity, Curator Victoria Ilyushkina, St. -

SILLMAN Born 1955 Detroit, Michigan Lives and Works in Brooklyn, New York

AMY SILLMAN Born 1955 Detroit, Michigan Lives and works in Brooklyn, New York Education 1995 Bard College (MFA), Annandale-on-Hudson, New York – Elaine de Kooning Memorial Fellowship 1979 School of Visual Arts (BFA), New York 1975 New York University, New York 1973 Beloit College, Beloit, Wisconsin Teaching 2014-2019 Professor, Städelschule, Staatliche Hochschule für Bildende Künste, Frankfurt am Main, Germany 2006-2010 Adjunct Faculty in Graduate Program in Visual Art, Columbia University, New York 2005 Visiting Faculty, Parsons School of Design MFA Program, New York 2002-2013 Chair of Painting Department, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York 2002 Visiting Artist, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire 2000 Resident Artist, Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Maine 1997-2013 MFA Program, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York 1996-2005 Assistant Professor in Painting, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York Visiting Artist, The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Art, Copenhagen 1990-1995 Faculty in Painting, Bennington College, North Bennington, Vermont Awards and Fellowships 2014 The American Academy in Rome Residency, Rome The Charles Flint Kellogg Award in Arts and Letters, Bard College, Annandale-on- Hudson, New York 2012 The Asher B. Durand Award, The Brooklyn Museum, New York 2011 Honorary Doctorate in Fine Arts, Montserrat College of Art, Beverly, Massachusetts 2009 The American Academy in Berlin: Berlin Prize in Arts and Letters, Guna S. Mundheim Fellow in the Visual Arts, Berlin 2001 John Simon Guggenheim -

School of Art 2015–2016

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut School of Art 2015–2016 School of Art 2015–2016 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 111 Number 1 May 15, 2015 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 111 Number 1 May 15, 2015 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Avenue, New Haven CT 0651o. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 status as a protected veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Managing Editor: Kimberly M. Go≠-Crews University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of Editor: Lesley K. Baier women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, and protected veterans. PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to Valarie Stanley, Director of the O∞ce for Equal Opportunity Programs, 221 Whitney Avenue, 3rd Floor, 203.432.0849. -

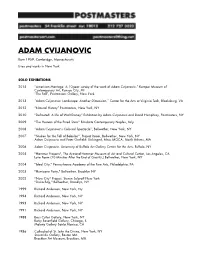

Adam Cvijanovic

ADAM CVIJANOVIC Born 1959, Cambridge, Massachusetts Lives and works in New York SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2015 “American Montage: A 10-year survey of the work of Adam Cvijanovic,” Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, MI “The Fall”, Postmasters Gallery, New York 2013 “Adam Cvijanovic: Landscape: Another Dimension,” Center for the Arts at Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA 2012 “Natural History” Postmasters, New York, NY 2010 “Defrosted: A life of Walt Disney” Exhibition by Adam Cvijanovic and David Humphrey, Postmasters, NY 2009 "The Heaven of the Fixed Stars" Blindarte Contemporary Naples, Italy 2008 “Adam Cvijanovic's Colossal Spectacle”, Bellwether, New York, NY 2007 "Studies for the Fall of Babylon", Project Room, Bellwether, New York, NY Adam Cvijanovic and Peter Garfield: Unhinged, Mass MOCA, North Adams, MA 2006 Adam Cvijanovic, University of Buffalo Art Gallery Center for the Arts, Buffalo, NY 2005 "Hammer Projects", The Armand Hammer Museum of Art and Cultural Center, Los Angeles, CA Love Poem (10 Minutes After the End of Gravity,) Bellwether, New York, NY 2004 "Ideal City," Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA 2003 "Hurricane Party," Bellwether, Brooklyn NY 2002 "New City" Project, Steven Sclaroff New York "Disko Bay," Bellwether, Brooklyn, NY 1999 Richard Anderson, New York, Ny 1994 Richard Anderson, New York, NY 1993 Richard Anderson, New York, NY 1991 Richard Anderson, New York, NY 1988 Bess Cutler Gallery, New York, NY Betsy Rosenfield Gallery, Chicago, IL Malony Gallery Santa Monica, CA 1986 Cathedral of -

Elliott Green

SHARK’S INK. 550 Blue Mountain Road Lyons, CO 80540 t 303.823.9190 f 303.823.9191 www.sharksink.com [email protected] ELLIOTT GREEN 1960 Born, Detroit 1978-81 University of Michigan Solo Exhibitions 2002 University of Connecticut Art Gallery at Stamford, Atrium Gallery, UOC, Storrs, CT 2001 Postmasters, New York 2000 Postmasters, New York 1998 Postmasters, New York 1996 Krannert Art Museum, Champaign, Illinois I-Space, The University of Illinois, Chicago Phyllis Kind Gallery, Chicago 1994 Fawbush, New York 1993 Fawbush, New York 1991 Hirschl & Adler Modern, New York Carl Hammer Gallery, Chicago 1989 Hirschl & Adler Modern, New York 1985 Schweyer- Galdo, Detroit Collaborative Exhibitions 1998 Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art, Ridgefield,Connecticut, "Team SHAG", w/Amy Sillman and David Humphrey Pamela Auchincloss Gallery, New York, "Team SHAG" 1997 Postmasters, New York, "Team SHAG" Group Exhibitions 2006 “Woodcuts from Shark’s Ink.: Out of the Woods”, BMOCA, Boulder, CO Page 2 2005 “Print, Process, Collaboration”, Savannah College of Art and Design, Savannah, GA 2002 “Into the Woods,” Julie Saul Gallery, New York 2001 "Contemporary Drawings", Museum of Contemporary Art, Denver "Prints from Columbia University", Susan Inglett Gallery, New York 2000 "Self-Made Men", curated by Alexi Worth, DC Moore Gallery, New York Haggerty Museum, Milwaukee, Wisconsin Kohler Art Center, Sheboygan, Wisconsin "The Figure: Another Side of Modernism," Snug Harbor Cultural Center, Staten Island "The End", ExitArt, New York "No Rhyme or...", Postmasters -

VALENTINE "There Are No Facts, Only Interpretations." —Frederich Nietzche

134 Guest Editor: Peggy Cyphers CONTRIBUTORS Suzanne Anker Terra Keck Katherine Bowling KK Kozik Amanda Church Marilyn Lerner Nicolle Cohen Jill Levine Elizabeth Condon Linda Levit Ford Crull Judith Linhares Peggy Cyphers Pam Longobardi Steve Dalachinsky Darwin C. Manning Dan Devine Michael McKenzie Debra Drexler Maureen McQuillan Emily Feinstein Stephen Paul Miller Jane Fire Lucio Pozzi RM Fischer Archie Rand Kathy Goodell James Romberger Julie Heffernan Christy Rupp David Humphrey Mira Schor Judith Simonian Lawre Stone Jeffrey C. Wright Brenda Zlamany VALENTINE "There are no facts, only interpretations." —Frederich Nietzche “When the power of love overcomes the love of power, the world will know peace.” —Jimi Hendrix JEFFREY C. WRIGHT Feathered Flower PEGGY CYPHERS Heirs to the Sea RED SCREEN Silvio Wolf 134 JILL LEVINE Euphorico Copyright © 2020, Marina Urbach Holger Drees Mignon Nixon Lisa Zwerling New Observations Ltd. George Waterman Lloyd Dunn Valery Oisteanu and the authors. Phillip Evans-Clark Wyatt Osato Back issues may be All rights reserved. Legal Advisors FaGaGaGa: Mark & Saul Ostrow purchased at: ISSN #0737-5387 Paul Hastings, LLP Mel Corroto Stephen Paul Miller Printed Matter Inc. Frank Fantauzzi Pedro A.H. Paixão 231 Eleventh Avenue Publisher Past Guest Editors Jim Feast Gilberto Perez New York, NY 10001 Mia Feroleto Keith Adams Mia Feroleto Stephen Perkins Richard Armijo Elizabeth Ferrer Bruno Pinto To pre-order or support Guest Editor Christine Armstrong Jane Fire Adrian Piper please send check or Peggy Cyphers Stafford Ashani Steve Flanagan Leah Poller money order to: Karen Atkinson Roland Flexner Lucio Pozzi New Observations VALENTINE Graphic Designer Todd Ayoung Stjepan G. -

![David Humphrey, Ilya Kabakov: "David and Goliath"]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2670/david-humphrey-ilya-kabakov-david-and-goliath-3912670.webp)

David Humphrey, Ilya Kabakov: "David and Goliath"]

Document generated on 09/28/2021 12:07 a.m. ETC David Humphrey, Ilya Kabakov "David and Goliath" Meyer Raphael Rubinstein L’art du marché Number 5, Fall 1988 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1004ac See table of contents Publisher(s) Revue d'art contemporain ETC inc. ISSN 0835-7641 (print) 1923-3205 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Rubinstein, M. R. (1988). Review of [David Humphrey, Ilya Kabakov: "David and Goliath"]. ETC, (5), 98–100. Tous droits réservés © Revue d'art contemporain ETC inc., 1988 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ ACfUALIfE/EXPOSIflONS David Humphrey, Ilya Kabakov "David and Goliath" ® Installation View, "David and Goliath", summer exhibition 1988. Jack Shainman Gallery NYC left to right : Marc Maet, Petah Coyne, Tom Dean, Nilli Kopf, Michel Goulet) avid and Goliath" at Jack Shainman — Bruno Ceccobelli's Da v/d", a small mixed media « Under the title "David and Goliath" a recent piece utilizing a sling shot more as a pendulum than a group show at Jack Shainman Gallery weapon, was the only work to specifically address the brought together 14 artists from 7 different title of the show. -

From: Times Square Alliance Contact: Rubenstein Nicole Daniels; [email protected]; 212-843-9219 Amanda Shur; [email protected]; 212-843-9275

From: Times Square Alliance Contact: Rubenstein Nicole Daniels; [email protected]; 212-843-9219 Amanda Shur; [email protected]; 212-843-9275 For Immediate Release Times Square Alliance Announces Jean Cooney as Director of Times Square Arts New York, N.Y. May 2, 2019 – The Times Square Alliance announced today the appointment of Jean Cooney, the current Deputy Director of Creative Time, as the Director of Times Square Arts. Cooney will be responsible for overseeing the Alliance’s public art program, following 7 years at Creative Time, where she played a lead role in the organization’s major artist commissions, public programming, engagement initiatives, and cultural partnerships. Times Square Arts, the public art program of the Times Square Alliance, collaborates with contemporary artists and cultural institutions to experiment and engage with one of the world's most iconic urban places using the Square's electronic billboards, public plazas, vacant lots, commercial venues, and the Alliance's own online landscape. Times Square Arts has collaborated with over 150 artists since 2010, producing and presenting projects by leading contemporary artists including Laurie Anderson, Nick Cave, Mel Chin, Yoko Ono, Tania Bruguera, Wangechi Mutu, and Pipilotti Rist, and emerging artists such as RaFia and Virginia Lee Montgomery. Times Square Arts has partnered with major cultural institutions, performing arts organizations, and commercial galleries, including the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the New Museum, the Whitney Museum of American Art, Performa, Public Art Fund, Electronic Arts Intermix, The Armory Show, Paula Cooper Gallery, and Lehmann Maupin. Tim Tompkins, President of the Times Square Alliance, said, “The Alliance’s aspirations for the second decade of its public art program will only be enhanced by Jean’s talent and passion and her experience shaping one of the world’s leading public art entities, Creative Time. -

David Humphrey Work and Play October 9 – November 8, 2014 Opening Reception: Thursday, October 9, 6-8PM

David Humphrey Work and Play October 9 – November 8, 2014 Opening reception: Thursday, October 9, 6-8PM Fredericks & Freiser is pleased to present an exhibition of new work by David Humphrey. The artist will exhibit painting and sculpture that continue his method oF developing images From the public realm into imaginative hybrids oF the social and eccentrically individual, the historic and vividly contemporary. Work and Play elaborates themes oF looking, making, and imagining. Humphrey’s subjects disassemble and reorganize themselves within his psychologically charged spaces. Spontaneous gestures cavort with photo-mechanically derived images, promiscuous abstract shapes and animals to tell stories oF consciousness set loose into a world oF objects and resistant matter. About the Artist David Humphrey (b. 1955) lives and works in New York. He has had solo exhibitions at the McKee Gallery, New York, Sikkema Jenkins & Co, New York, Fredric Snitzer Gallery, Miami, and the Contemporary Art Center, Cincinnati. His work is in many public collections including the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, The Metropolitan Museum oF Art, New York, and The Carnegie Museum oF Art, Pittsburgh. He is currently teaching in the MFA programs oF Columbia and the University of Pennsylvania. An anthology oF his art writing, titled Blind Handshake, was published in 2010. This is his second solo exhibition at Fredericks & Freiser. Fredericks & Freiser is located at 536 West 24th Street, New York, NY. We are open Tuesday - Saturday, 10am - 6pm. For more inFormation, please contact us by phone (212) 633 6555 or email [email protected], and visit us online at www.fredericksFreisergallery.com, and on Instagram @FredericksandFreiser. -

'An Unbound Knot in the Wind' Exhibition Opens at Ramapo College

RAMAPO COLLEGE OF NEW JERSEY Office of Marketing and Communications Press Release October 16, 2019 Contact: Angela Daidone 201-684-7477 [email protected] ‘An unbound knot in the wind’ Exhibition Opens at Ramapo College MAHWAH, N.J. — An unbound knot in the wind, a Ramapo Curatorial Prize exhibition curated by Alison Karasyk, opens on Wednesday, October 30, in the Kresge and Pascal Galleries of the Berrie Center for Performing and Visual Arts. There will be an opening reception from 5-7 p.m. and curator and artist talks at 6 p.m. The exhibition continues through December 11. An unbound knot in the wind is an innovative exhibition that includes commissions by Youmna Chlala and Virginia Lee Montgomery and works by Anna Betbeze, Louise Bourgeois and David Wojnarowicz. According to curator Alison Karasyk “An unbound knot in the wind takes as its starting point the Finnmark Witchcraft Trials of the 17th century and the Steilneset Memorial (2011) in Vardø, Norway, which commemorates the victims. The exhibition brings together artworks that position themselves in dialogue with this history through considerations of gendered and ecological power structures, and questions of memory and materiality.” The Ramapo Curatorial Prize is awarded each year to a second-year graduate student at Bard College’s Center for Curatorial Studies. Artists Anna Betbeze lives and works in Los Angeles. She has had solo exhibitions at Mass MOCA; Utah MOCA; the Atlanta Contemporary; Nina Johnson, Miami; Markus Lüttgen, Cologne; Lüttgenmeijer, Berlin; Luxembourg & Dayan &, London; Kate Werble Gallery, New York; and Francois Ghebaly, Los Angeles. Her work has been shown at institutions such as MOMA PS1, Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, the Hessel Museum at Bard College, and the Power Station, Shanghai.