Development of the Early Childhood Curricular Beliefs Inventory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction 1

00_Macblain_Prelims.indd 1 12/20/2017 5:56:58 PM Sara Miller McCune founded SAGE Publishing in 1965 to support the dissemination of usable knowledge and educate a global community. SAGE publishes more than 1000 journals and over 800 new books each year, spanning a wide range of subject areas. Our growing selection of library products includes archives, data, case studies and video. SAGE remains majority owned by our founder and after her lifetime will become owned by a charitable trust that secures the company’s continued independence. Los Angeles | London | New Delhi | Singapore | Washington DC | Melbourne 00_Macblain_Prelims.indd 2 12/20/2017 5:56:59 PM 00_Macblain_Prelims.indd 3 12/20/2017 5:56:59 PM SAGE Publications Ltd Sean MacBlain 2018 1 Oliver’s Yard 55 City Road Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or London EC1Y 1SP private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, this publication SAGE Publications Inc. may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form, or by 2455 Teller Road any means, only with the prior permission in writing of the Thousand Oaks, California 91320 publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside B 1/I 1 Mohan Cooperative Industrial Area those terms should be sent to the publishers. Mathura Road New Delhi 110 044 SAGE Publications Asia-Pacific Pte Ltd 3 Church Street -

Lev Vygotsky Speaks: Early Childhood Curricula Dakota L

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current Honors College Spring 2015 Lev Vygotsky Speaks: Early childhood curricula Dakota L. Gagliardi James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors201019 Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Educational Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Gagliardi, Dakota L., "Lev Vygotsky Speaks: Early childhood curricula" (2015). Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current. 116. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors201019/116 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: VYGOSKY SPEAKS Lev Vygotsky Speaks: Early Childhood Curricula _______________________ An Honors Program Project Presented to the Faculty of the Undergraduate College of Education James Madison University _______________________ by Dakota Leigh Gagliardi May 2015 Accepted by the faculty of the Department of Early, Elementary and Reading Education (EERE), James Madison University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors Program. FACULTY COMMITTEE: HONORS PROGRAM APPROVAL: Project Advisor: Dorothy Sluss, Ph.D., Philip Frana, Ph.D., Professor, EERE Interim Director, Honors Program Reader: Susan Barnes, Ph.D., Associate Professor, EERE Reader: Shin Ji Kang, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, EERE PUBLIC PRESENTATION This work is accepted for presentation, in part or in full, at the Virginia Association for Early Childhood Education (VAECE) Conference in Richmond, Virginia on March 21, 2015. VYGOTSKY SPEAKS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Dr. -

Early Childhood

Early Childhood How Aistear was developed: Research Papers Early Childhood Early Childhood Education > How Aistear was Developed: Research Papers View the full Aistear document online The National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA) commissioned four research papers to inform the work in developing Aistear: the Early Childhood Curriculum Framework. Drawing on national and international research, these papers look at how: • particular understandings of education and care impact on children’s experiences during early childhood education • children learn and develop in early childhood • play can be used to extend and enhance children’s learning and development • formative assessment can support and extend early learning and development. Early Childhood Early Childhood Education > How Aistear was Developed: Research Papers Want to read more? Read a summary of the key messages from the research papers. Click on the links below to go to the papers and/or their executive summaries. 1. Education and care Perspectives on the relationship between education and care in early childhood (Hayes, 2007) • Research paper • Executive summary 2. Learning and development Children’s early learning and development (French, 2007) • Research paper • Executive summary 3. Play Play as a context for early learning and development (Kernan, 2007) • Research paper • Executive summary 4. Formative assessment Supporting early learning and development through formative assessment (Dunphy, 2008) • Research paper • Executive summary [home] Key messages from the research papers © NCCA 2009 National Council for Curriculum and Assessment 24 Merrion Square, Dublin 2. www.ncca.ie Aistear: the Early Childhood Curriculum Framework Key messages from the research papers Introduction Early childhood in Ireland is from birth to six years. -

THE HIGHSCOPE APPROACH: LEARNING THROUGH ACTION.Pdf

EXPEDUCOM ,MM A HANDBOOK ON EXPERIENTIAL EDUCATION. PEDAGOGICAL GUIDELINES FOR TEACHERS AND PARENTS Erasmus+ Project: Experiential Education Competence (teaching children aged 3-12) – EXPEDUCOM The grant reference number: 2014-1-LT01-KA200-000368 Editors: Gianina-Ana MASSARI Florentina-Manuela MIRON Violeta KAMANTAUSKIENE Zeynep ALAT Cristina MESQUITA Marina TZAKOSTA Jan Karel VERHEIJ Tija ZIRINA EDITURA UNIVERSITĂȚII ”ALEXANDRU IOAN CUZA” DIN IAȘI 1 Editors: Gianina-Ana MASSARI Florentina-Manuela MIRON Violeta KAMANTAUSKIENE Zeynep ALAT Cristina MESQUITA Marina TZAKOSTA Jan Karel VERHEIJ Tija ZIRINAA A HANDBOOK ON EXPERIENTIAL EDUCATION. PEDAGOGICAL GUIDELINES FOR TEACHERS AND PARENTS 2016 EDITURA UNIVERSITĂȚII ”ALEXANDRU IOAN CUZA” DIN IAȘI 2 Gianina-Ana MASSARI Florentina-Manuela MIRON Violeta KAMANTAUSKIENE Zeynep ALAT Cristina MESQUITA Marina TZAKOSTA Jan Karel VERHEIJ Tija ZIRINA Erasmus+ Project Title: Experiential Education Competence (teaching children aged 3-12) EXPEDUCOM The grant reference number: 2014-1-LT01-KA200-000368 Descrierea CIP a Bibliotecii Naționale a României: MASSARI, Gianina-Ana, MIRON, Florentina-Manuela, Violeta KAMANTAUSKIENE A Handbook on Experiential Education. Pedagogical Guidelines for Teachers and Parents / Gianina-Ana Massari; - Iași: Editura Universității Alexandru Ioan Cuza din Iași, 2016 ISBN 978-606-714-309-6 3 HANDBOOK CONTENTS Foreword (Violeta Kamantauskiene) 7 PART A. 9 GENERAL FRAMEWORK ON EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING CHAPTER 1. WHAT IS EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING? 10 (Gianina-Ana Massari, Manuela-Florentina Miron) …….…… 1.1. Concept …………………………………………………. 12 1.2. Characteristics of experiential based learning………. 14 1.3. The principals of experiential orientation…………….. 17 1.4. Experiential based learning stages…………………… 18 1.5. Teacher roles……………………………………..……... 19 1.6. Children roles …………………………………………… 20 1.7. Integration of experiential learning in teaching …….… 20 CHAPTER 2. -

How Children Learn

Books How children learn Educational theories and approaches – from Comenius the father of modern education to giants such as Piaget, Vygotsky and Malaguzzi by Linda Pound Contents Introduction 2 Jerome Bruner 63 John Comenius 4 Chris Athey and schema theory 67 Jean-Jacques Rousseau 6 Loris Malaguzzi and early education in Reggio Emilia 71 Johann Pestalozzi 9 Paulo Freire 75 Robert Owen 13 David Weikart and the HighScope approach 78 Friedrich Froebel 17 Margaret Donaldson and post-Piagetian theories 83 Sigmund Freud and psychoanalytic theories 21 Howard Gardner and multiple intelligence theory 87 John Dewey 27 Te Whariki 92 Margaret McMillan 31 Forest schools 96 Rudolf Steiner and Steiner Waldorf education 34 Learning through play 100 Maria Montessori and the Montessori method 38 Research into brain development 105 Susan Isaacs 42 Jean Piaget 46 Emotional intelligence 110 Lev Vygotsky 51 References and where to find out more 114 Burrhus Skinner and behaviourism 55 Index 120 John Bowlby and attachment theory 59 Acknowledgements 124 Published by Practical Pre-School Books, A Division of MA Education Ltd, St Jude’s Church, Dulwich Road, Herne Hill, London, SE24 0PB. Tel: 020 7738 5454 www.practicalpreschoolbooks.com Associate Publisher: Angela Morano Shaw © MA Education Ltd 2014. Photos on cover by Lucie Carlier Design: Alison Cutler fonthillcreative 01722 717043 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright of material in this book and the publisher apologises for any inadvertent omissions. -

Curriculum in Early Childhood Education

CURRICULUM IN EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION Curriculum in Early Childhood Education: Re-examined, Rediscovered, Renewed provides a critical examination of the sources, aims, and features of early childhood curricula. Providing a theoretical and philosophical foundation for examining teaching and learning, this book will provoke discussion and analysis among all readers. How has theory been used to understand, develop, and critique curriculum? Whose per- spectives are dominant and whose are ignored? How is diversity addressed? What values are explicit and implicit? The book first contextualizes the historical and research base of early childhood curriculum, and then turns to discussions of various schools of theory and philoso- phy that have served to support curriculum development in early childhood education. An examination of current curriculum frameworks is offered, from both the US and abroad, including discussion of the Project Approach, Creative Curriculum, Te Wha-riki, and Reggio Emilia. Finally, the book closes with chapters that enlarge the topic to curriculum-being-enacted through play and that summarize key issues while pointing out future directions for the field. Offering a broad foundation for examining cur- riculum in early childhood, readers will emerge with a stronger understanding of how theories and philosophies intersect with curriculum development. Nancy File is Associate Professor in Early Childhood Education at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Jennifer J. Mueller is Associate Professor in Early Childhood Education at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Debora Basler Wisneski is Associate Professor in Early Childhood Education at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. CURRICULUM IN EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION Re-examined, Rediscovered, Renewed Edited by Nancy File, Jennifer J. -

Highscope Prekindergarten Program Summary

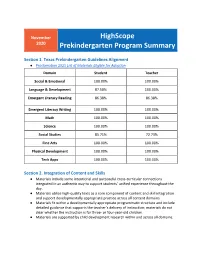

November HighScope 2020 Prekindergarten Program Summary Section 1. Texas Prekindergarten Guidelines Alignment ● Proclamation 2021 List of Materials Eligible for Adoption Domain Student Teacher Social & Emotional 100.00% 100.00% Language & Development 87.50% 100.00% Emergent Literacy Reading 86.38% 86.38% Emergent Literacy Writing 100.00% 100.00% Math 100.00% 100.00% Science 100.00% 100.00% Social Studies 85.71% 72.73% Fine Arts 100.00% 100.00% Physical Development 100.00% 100.00% Tech Apps 100.00% 100.00% Section 2. Integration of Content and Skills ● Materials include some intentional and purposeful cross-curricular connections integrated in an authentic way to support students’ unified experience throughout the day. ● Materials utilize high-quality texts as a core component of content and skill integration and support developmentally appropriate practice across all content domains. ● Materials fit within a developmentally appropriate programmatic structure and include detailed guidance that supports the teacher’s delivery of instruction; materials do not clear whether the instruction is for three- or four-year-old children. ● Materials are supported by child development research within and across all domains. Section 3. Health and Wellness Associated Domains ● Materials include some direct social skill instruction and explicit teaching of skills. Students repeatedly practice social skills throughout the day. ● Materials include guidance for teachers on classroom arrangements that promote positive social interactions. ● Materials include some activities to develop physical skills, fine motor skills, and safe and healthy habits. Section 4. Language and Communication Domain ● Materials provide some guidance on developing students’ listening and speaking skills as well as expanding student vocabulary.