Teanaway Watershed Aquatic Species Environmental Baseline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Teanaway: Geologic & Physical Geographic Patterns

Ellensburg Chapter Ice Age Floods Institute The Teanaway: Geologic & Physical Geographic Patterns Field Trip Leader: Dr. Karl Lillquist Geography Department Central Washington University 29 September 2013 1 Preliminaries Field Trip Overview: Itinerary: The State of Washington is in the 11:00 am Depart CWU process of purchasing ~50,000 acres of 11:30 Stop 1—Lambert Road private forest lands in the Teanaway River Watershed. This Eastern Cascade 12:15 pm Depart drainage contains prime fish and 12:30 Stop 2—Ballard Hill Road wildlife habitat, and is a key piece of 1:00 Depart the Yakima River Basin water puzzle. 1:15 Stop 3—Cheese Rock 2:45 Depart We will explore the geology and 3:00 29 Pines CG Toilet Stop physical geography of the soon-to-be purchased lands as well as private and 3:15 Depart adjacent U.S. Forest Service lands in 3:30 Stop 4—Teanaway Grd Stn the Teanaway River Watershed. Our 4:00 Depart focus will be on the different bedrock 4:15 Stop 5—Iron Peak Trail and landforms of the watershed. Columbia River basalts, Roslyn 5:00 Depart sandstone, Teanaway basalt, Swauk 6:00 Arrive at CWU sandstone, and Ingalls Tectonic Complex are all found in the area. These varied lithologies have been shaped by unique Eastern Cascade weather and climate patterns resulting in river processes, weathering, landslides, and glaciers over time. 2 En route to Stop 1 Our route to Stop 1: Fans (Waitt, 1979; Tabor et al, 1982). Drive south on D street to University Over time, these fans became stable Way, then west on University Way to (perhaps because of slowing tectonic WA 10. -

Chapter 11. Mid-Columbia Recovery Unit Yakima River Basin Critical Habitat Unit

Bull Trout Final Critical Habitat Justification: Rationale for Why Habitat is Essential, and Documentation of Occupancy Chapter 11. Mid-Columbia Recovery Unit Yakima River Basin Critical Habitat Unit 353 Bull Trout Final Critical Habitat Justification Chapter 11 U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service September 2010 Chapter 11. Yakima River Basin Critical Habitat Unit The Yakima River CHU supports adfluvial, fluvial, and resident life history forms of bull trout. This CHU includes the mainstem Yakima River and tributaries from its confluence with the Columbia River upstream from the mouth of the Columbia River upstream to its headwaters at the crest of the Cascade Range. The Yakima River CHU is located on the eastern slopes of the Cascade Range in south-central Washington and encompasses the entire Yakima River basin located between the Klickitat and Wenatchee Basins. The Yakima River basin is one of the largest basins in the state of Washington; it drains southeast into the Columbia River near the town of Richland, Washington. The basin occupies most of Yakima and Kittitas Counties, about half of Benton County, and a small portion of Klickitat County. This CHU does not contain any subunits because it supports one core area. A total of 1,177.2 km (731.5 mi) of stream habitat and 6,285.2 ha (15,531.0 ac) of lake and reservoir surface area in this CHU are proposed as critical habitat. One of the largest populations of bull trout (South Fork Tieton River population) in central Washington is located above the Tieton Dam and supports the core area. -

Post-Glacial Fire History of Horsetail Fen and Human-Environment Interactions in the Teanaway Area of the Eastern Cascades, Washington

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses Winter 2019 Post-Glacial Fire History of Horsetail Fen and Human-Environment Interactions in the Teanaway Area of the Eastern Cascades, Washington Serafina erriF Central Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Environmental Education Commons, Environmental Monitoring Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Other Environmental Sciences Commons, and the Sustainability Commons Recommended Citation Ferri, Serafina, "Post-Glacial Fire History of Horsetail Fen and Human-Environment Interactions in the Teanaway Area of the Eastern Cascades, Washington" (2019). All Master's Theses. 1124. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/1124 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POST-GLACIAL FIRE HISTORY OF HORSETAIL FEN AND HUMAN-ENVIRONMENT INTERACTIONS IN THE TEANAWAY AREA OF THE EASTERN CASCADES, WASHINGTON __________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty Central Washington University ___________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Resource Management ___________________________________ by Serafina Ann Ferri February 2019 CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Graduate Studies -

Chapter 2. Ecosystem Profile

CHAPTER 2. ECOSYSTEM PROFILE 2.1 Introduction Kittitas County is situated in central Washington on the eastern slopes of the Cascade Mountains, between the Cascade Crest and the Columbia River in the Columbia River basin. The county is contained within three major basins: Upper Yakima (Water Resource Inventory Area [WRIA] 39), Alkali – Squilchuck (WRIA 40), and Naches basin (WRIA 38). Of the 2,297 square miles that constitutes Kittitas County, the majority, 78 percent, lies within the Upper Yakima basin (WRIA 39), which drains into the Yakima River. The Alkali – Squilchuck basin (WRIA 40) comprises 17 percent of the county in the eastern portion and drains into the Columbia River. The remaining 5 percent of the county is contained in the Naches basin (WRIA 38) on its southwestern edge and drains into the Little Naches River, which becomes the Naches River joining the Yakima River in Yakima County. Figure 2-1 shows the locations of the WRIAs in Kittitas County. Four different ecoregions are found within Kittitas County: North Cascades, Cascades, Eastern Cascades Slopes and Foothills, and Columbia Plateau (Figure 2-2). The North Cascades ecoregion, found in the northwestern portion of the county, is characterized by glaciated valleys and narrow-crested ridges punctuated by rugged, high relief peaks approaching 8,000 feet above mean sea level (AMSL). It is forested with fir, hemlock, and, in the drier eastern margins, pine. The Cascades ecoregion, located in southwestern Kittitas County, is similar to the North Cascades, but in contrast has more gently undulating terrain, the climate is more temperate, and there is less occurrence of ponderosa pine. -

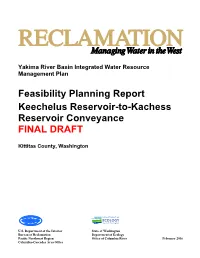

Feasibility Planning Report Keechelus Reservoir-To-Kachess Reservoir Conveyance FINAL DRAFT

Yakima River Basin Integrated Water Resource Management Plan Feasibility Planning Report Keechelus Reservoir-to-Kachess Reservoir Conveyance FINAL DRAFT Kittitas County, Washington U.S. Department of the Interior State of Washington Bureau of Reclamation Department of Ecology Pacific Northwest Region Office of Columbia River February 2016 Columbia-Cascades Area Office MISSION STATEMENTS U.S. Department of the Interior Protecting America’s Great Outdoors and Powering our Future. The U.S. Department of the Interior protects America’s natural resources and heritage, honors our cultures and Tribal communities, and supplies the energy to power our future. Bureau of Reclamation The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. Washington State Department of Ecology The Mission of the Washington State Department of Ecology is to protect, preserve and enhance Washington’s environment, and promote the wise management of our air, land, and water for the benefit of current and future generations. If you need this document in a format for the visually impaired, call the Office of Columbia River at (509) 575-2490. Persons with hearing loss can call 711 for Washington Relay Service. Persons with a speech disability can call 877-833-6341. Keechelus-to-Kachess Conveyance ¬906 « Legend 90 Major Road ¦§¨ 90 ¦§¨ 6 Portal Hyak Alternative 1 (North Tunnel Alignment) Alternative 2 (South Tunnel Alignment) Conveyance Option A Conveyance Option B Alternative 1, 6 Keechelus North Tunnel 6 Reservoir " 90 V ¦§¨ d i a µ R 6 e 0 7,000 k K a a L c Feet ss h he e Kachess N 0 1.25 ac s K s F - " Reservoir 4 Miles R 8 Alternative 2, d 1 6 8 ( South Tunnel K a Keechelus Reservoir c Note: General location of the Kachess Drought h N " Kachess Reservoir e Relief Pumping Plant (KDRPP). -

FINAL Manastash Creek Biological Assessment

Biological Assessment of Potential Effects to Middle Columbia River Steelhead from the MANASTASH CREEK WATER CONSERVATION AND TRIBUTARY ENHANCEMENT PROJECT Yakima River Basin Water Enhancement Project Yakima Project, Washington U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Pacific Northwest Region Columbia-Cascades Area Office Yakima, Washington February 2013 Mission Statements U.S. Department of the Interior Protecting America's Great Outdoors and Powering Our Future The U.S. Department of the Interior protects America’s natural resources and heritage, honors our cultures and tribal communities, and supplies the energy to power our future. Bureau of Reclamation The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. Biological Assessment of Potential Effects to Middle Columbia River Summer Steelhead from the Manastash Creek Water Conservation and Tributary Enhancement Project Prepared For: National Marine Fisheries Service 510 Desmond Drive S.E., Suite 100 Lacey, WA 98503-1273 Prepared By: U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Pacific Northwest Region Columbia-Cascades Area Office Yakima, WA 98901 February 15, 2013 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 1 Purpose of this Document ................................................................................................. -

Geoengineers, Inc

600 Dupont Street Bellingham, Washington 98225 360.647.1510 October 29, 2009 American Forest Land Company, LLC 965 Grand Boulevard Bellingham, Washington 98226 Attention: Wayne Schwandt Subject: Water Resource Consulting Services Teanaway Subarea Planning Process Kittitas County, Washington GeoEngineers, Inc. File No. 17700-001-02 INTRODUCTION This letter report provides a preliminary evaluation of water resources owned and managed by the American Forest Land Company, LLC (AFLC). AFLC owns a number of water rights that authorize various uses of the Teanaway River and its tributaries in the Teanaway River Subarea of Kittitas County, Washington. The water rights are located and used on a portion of the approximately 50,000 acres owned and managed by AFLC within the Teanaway River subbasin, located within Water Resource Inventory Area (WRIA) 39. This preliminary evaluation of AFLC’s rights and summary of means to change rights responds to inquiries from participants in the Teanaway Subarea Planning Process (Teanaway SPP). The findings and conclusions developed by GeoEngineers are based on review of a report completed by Perkins Coie, review of water rights records summarized in that report, review of site maps and photographs, prior experience in the Yakima and Teanaway River subbasins, and experience with water resource management in Washington State. SITE DESCRIPTION The Teanaway River basin is located on the eastern flank of the Cascade Mountains, north and northeast of the town of Cle Elum, Washington. The drainage basin is approximately 200 square miles in area, ranging between approximately 6000 feet above mean sea level (MSL) in the headwaters to approximately 1800 feet MSL at its confluence with the Yakima River. -

Yakama Nation Pacific Lamprey Project 2017 Annual Report

Yakama Nation Pacific Lamprey Project 2017 Annual Report Project No. 2008-470-00 Report was completed under BPA Contract No. 56662 REL 123 Report covers work performed from: January 2017 – December 2017 Ralph Lampman, Tyler Beals, Dave’y Lumley, Sean Goudy, Leona Wapato, and Robert Rose Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation Yakama Nation Fisheries Resource Management Program P. O. Box 151, Toppenish, Washington 98948, USA Report Created: March, 2018 1 Cover Photo: Yakama Nation Tribal School (Toppenish, WA) and Christian Brothers High School (Sacramento, CA) students jointly releasing adult Pacific Lamprey in Satus Creek on March 30, 2017. This document should be cited as follows: Lampman, R., T. Beals, S. Goudy, D. Lumley, L. Wapato, and R. Rose. 2018. Yakama Nation Pacific Lamprey Project. 2017 Annual Report to the Bonneville Power Administration, Portland, OR. Project No. 2008-470-00. Bonneville Power Administration P.O. Box 3621, Portland, OR 97208 This report was primarily funded by the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA), U.S. Department of Energy, as part of BPA's program to protect, mitigate, and enhance fish and wildlife affected by the development and operation of hydroelectric facilities on the Columbia River and its tributaries. The views in this report are the author's and do not necessarily represent the views of BPA. 2 Table of Contents I. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ 5 II. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ -

Teanaway Magic Lofty Peaks, Geologic Wonders and Great Summertime Hikes Beckon in the Alpine Lakes AUER B LAN A

Teanaway Magic Lofty peaks, geologic wonders and great summertime hikes beckon in the Alpine Lakes AUER B LAN A The relatively dry Teanaway region north of Cle Elum is rich in wildflowers and panoramic views. Here, hiker Gary Jackson traverses Teanaway Ridge, with the peaks of the Stuart Range in the distance. By Joan Burton green and marshy in places, with a few The name refers to the combination of late asters, and the creek was running. the drainages of Iron and Bear Hikes in the Teanaway River area Springs high on the slope of Navaho Creeks. Steep switchbacks take you up have a special charm. Weather is often fed it, we decided. We had a warm through meadows bright with scarlet clearer in early spring or late fall when clear night, so warm that we hardly gilia, golden balsamroot, yellow bell, skies on the west side of the Cascades needed our tents, and woke ready to Jeffrey shooting stars, chocolate lily, are gray and dripping. That feature wander upward. Since one of us was calypso orchids, blue camas, white alone justifies the two-and-a-half hour recovering from surgery, we didn’t (death) camas, lomatium, white fawn drive to trailheads for me, but there expect to go far. To our surprise, the lily, yellow monkey flower, sea blush, are also unique sights to be seen trail up Navaho was a highway over a small flowered blue-eyed Mary, there. Flowers are abundant, some bare, serpentine ridge, and in an hour miners’ lettuce and Siberian miners’ unique to the area, and larch displays and a half we stood on the 7,200-foot lettuce, red flowering currant, are magnificent in late fall. -

Teanaway Community Forest Fish and Wildlife Habitat Baseline Report

Teanaway Community Forest Fish and Wildlife Habitat Baseline Report Report submitted to Department of Ecology’s Office of Columbia River by Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife in partial fulfillment of Contract # C1400237 0 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Teanaway Community Forest .......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Description of what WDFW was tasked to provide to Washington State Department of Ecology . 1 1.3 Timeline of work, field and office .................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Water Supply and Watershed Protection ............................................................... 3 2.1 Wetland surveys .............................................................................................................................. 3 2.1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 3 2.1.2 Methods .................................................................................................................................. 4 2.1.3 Results ..................................................................................................................................... 6 2.1.4 Discussion ............................................................................................................................. -

Hydrogeologic Framework and Groundwater/Surface-Water Interactions of the Upper Yakima River Basin, Kittitas County, Central Washington

Prepared in cooperation with the Washington State Department of Ecology and Kittitas County Hydrogeologic Framework and Groundwater/Surface-Water Interactions of the Upper Yakima River Basin, Kittitas County, Central Washington Scientific Investigations Report 2014–5119 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: View of upper Yakima River Basin from South Cle Elum Ridge, south of Roslyn, Washington, looking northwest; Cle Elum and Kachess Lakes in background. Photograph taken by James D. Patterson, U.S. Geological Survey, June 25, 2014. Hydrogeologic Framework and Groundwater/Surface-Water Interactions of the Upper Yakima River Basin, Kittitas County, Central Washington By Andrew S. Gendaszek, D. Matthew Ely, Stephen R. Hinkle, Sue C. Kahle, and Wendy B. Welch Prepared in cooperation with the Washington State Department of Ecology and Kittitas County Scientific Investigations Report 2014–5119 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2014 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. -

NRCS - Teanaway River Bank Protection Project Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service 2021 E

United States Department of the Interior FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE Washington Fish and Wildlife Office Central Washington Field Office 215 Melody Lane, Suite 119 Wenatchee, WA 98801 September 8, 2011 In Reply Refer To: USFWS Reference: 13260-2011-F-0093 Hydrologic Unit Codes: 17-03-00-01-02 RE: Teanaway River Bank Protection Project Roylene Rides-at-the-Door Washington State Conservationist Natural Resources Conservation Service 2021 E. College Way, Suite 206 Mount Vemon, Washington 98273-2373 Dear Ms. Rides-at-the-Door: This conespondence transmits the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's (Service) Biological Opinion (BO) based upon our review of the proposed Teanaway River Bank Protection Project (Project). The attached BO describes the effects of the Project on the bull trout (Salvelinus confluentus) and designated critical habitat for the bull trout in accordance with Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act (Act) of 1973, as amended (16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq.). The July 1,2011, cover letter and final Biological Assessment (BA) for this Project were received in the Service's Central Washington Field Office (CWFO) on July 5, 2011. The complete record for this consultation is on file in the CWFO. The attached BO describes the effects of the Project on the bull trout and its designated critical habitat. The Service concludes in the attached BO that implementation of the Project is not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of the bull trout and will not result in the destruction or adverse modification of designated critical habitat for the bull trout. If you have further questions about this BO or your responsibilities under the Act, please contact Gregg Kurz of the CWFO in Wenatchee at 509-665-3508.