Global Anglicansummer 2020 Established in 1879 As the Churchman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Five Points of Calvinism

• TULIP The Five Points of Calvinism instructor’s guide Bethlehem College & Seminary 720 13th Avenue South Minneapolis, MN 55415 612.455.3420 [email protected] | bcsmn.edu Copyright © 2007, 2012, 2017 by Bethlehem College & Seminary All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, modified, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Scripture taken from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version. Copyright © 2007 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. • TULIP The Five Points of Calvinism instructor’s guide Table of Contents Instructor’s Introduction Course Syllabus 1 Introduction from John Piper 3 Lesson 1 Introduction to the Doctrines of Grace 5 Lesson 2 Total Depravity 27 Lesson 3 Irresistible Grace 57 Lesson 4 Limited Atonement 85 Lesson 5 Unconditional Election 115 Lesson 6 Perseverance of the Saints 141 Appendices Appendix A Historical Information 173 Appendix B Testimonies from Church History 175 Appendix C Ten Effects of Believing in the Five Points of Calvinism 183 Instructor’s Introduction It is our hope and prayer that God would be pleased to use this curriculum for his glory. Thus, the intention of this curriculum is to spread a passion for the supremacy of God in all things for the joy of all peoples through Jesus Christ. This curriculum is guided by the vision and values of Bethlehem College & Seminary which are more fully explained at bcsmn.edu. At the Bethlehem College & Semianry website, you will find the God-centered philosophy that undergirds and motivates everything we do. -

The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus by Philip Schaff About ANF01

ANF01. The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus by Philip Schaff About ANF01. The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus by Philip Schaff Title: ANF01. The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus URL: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf01.html Author(s): Schaff, Philip (1819-1893) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: The Ante-Nicene Christian library is meant to comprise translations into English of all the extant works of the Fathers down to the date of the first General Council held at Nice in A.D. 325. The sole provisional exception is that of the more bulky writings of Origen. It is intended at present only to embrace in the scheme the Contra Celsum and the De Principiis of that voluminous author; but the whole of his works will be included should the undertaking prove successful. Publication History: Text edited by Rev. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson and first published in Edinburgh, 1867. Additional introductionary material and notes provided for the American edition by A. Cleveland Coxe 1886. Print Basis: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, reprint 2001 Source: Logos Research Systems, Inc. Rights: Public Domain Date Created: 2002-10 Status: Proof reading, ThML markup and subject index for Version 3.0 by Timothy Lanfear General Comments: Hebrew and Greek were checked against page scans of the 1995 Hendrickson reprint by SLK; errors in the hard copy have not been corrected in this digitized text. Contributor(s): Timothy Lanfear (Markup) CCEL Subjects: All; Early Church; Classic; Proofed; LC Call no: BR60 LC Subjects: Christianity Early Christian Literature. -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Edinburgh Research Explorer 'Dating the Death of Jesus' Citation for published version: Bond, H 2013, ''Dating the Death of Jesus': Memory and the Religious Imagination', New Testament Studies, vol. 59, no. 04, pp. 461-475. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0028688513000131 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1017/S0028688513000131 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: New Testament Studies Publisher Rights Statement: © Helen Bond, 2013. Bond, H. (2013). 'Dating the Death of Jesus': Memory and the Religious Imagination. New Testament Studies, 59(04), 461-475doi: 10.1017/S0028688513000131 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 Dating the Death of Jesus: Memory and the Religious Imagination Helen K. Bond School of Divinity, University of Edinburgh, Mound Place, Edinburgh, EH1 2LX [email protected] After discussing the scholarly preference for dating Jesus’ crucifixion to 7th April 30 CE, this article argues that the precise date can no longer be recovered. All we can claim with any degree of historical certainty is that Jesus died some time around Passover (perhaps a week or so before the feast) between 29 and 34 CE. -

Currents in Reformed Theology Vol

UNION WITH CHRIST Currents in Reformed Theology Vol. 4, No. 1 / April 2018 4, No. Vol. Westminster International Theological Reformed Seminary Evangelical Philadelphia Seminary uniocc.com Vol. 4, No. 1 / April 2018 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF REFORMED THEOLOGY AND LIFE Editorial Board Members Africa Flip Buys, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa Henk Stoker, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa Philip Tachin, National Open University of Nigeria, Lagos, Nigeria Cephas Tushima, ECWA Theological Seminary, Jos, Nigeria Asia In-Sub Ahn, Chong Shin University and Seminary, Seoul, Korea UNION WITH CHRIST Wilson W. Chow, China Graduate School of Theology, Hong Kong Matthew Ebenezer, Presbyterian Theological Seminary, Dehra Dun, India Editorial Committee and Staff Benyamin F. Intan, International Reformed Evangelical Seminary, Jakarta, Indonesia Editor in Chief: Paul Wells Kevin Woongsan Kang, Chongshin Theological Seminary, Seoul, Korea Senior Editors: Peter A. Lillback and Benyamin F. Intan In Whan Kim, Daeshin University, Gyeongsan, Gyeongbuk, Korea Managing Editor: Bernard Aubert Billy Kristanto, International Reformed Evangelical Seminary, Jakarta, Indonesia Book Review Editor: Brandon D. Crowe Jong Yun Lee, Academia Christiana of Korea, Seoul, Korea Subscription Manager: Audy Santoso Sang Gyoo Lee, Kosin University, Busan, Korea Assistant: Lauren Beining Deok Kyo Oh, Ulaanbaatar University, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia Copy Editor: Henry Whitney Moses Wong, China Reformed Theological Seminary, Taipei, Taiwan Typesetter: Janice Van Eck Australia Mission Statement Allan M. Harman, Presbyterian Theological College, Victoria, Australia Peter Hastie, Presbyterian Theological College, Victoria, Australia Unio cum Christo celebrates and encourages the visible union believers possess Mark D. Thompson, Moore Theological College, Newtown, Australia in Christ when they confess the faith of the one holy catholic and apostolic church, the body of Christ. -

175 YEARS by David Phillips

Article reprinted from Cross†Way Issue Winter 2011 No. 119 (C)opyright Church Society; material may be used for non-profit purposes provided that the source is acknowledged and the text is not altered. 175 YEARS By David Phillips We have let it go by without really mentioning but the year just passed marked the 175th anniversary of the founding of the first of Church Society’s forebears, the Protestant Association. This article, to be continued in the next issue is based on a recent talk looking at the history, work and issues facing Church Society. Church Association We begin not at the beginning, but with Church Association founded in 1865. It was established to uphold the protestant and reformed faith of the Church of England, and to oppose the introduction of ritualistic practices and the doctrines that lay behind them. Those practices included such things as stone altars, medieval mass vestments, adoration of the bread and wine at communion and so on. The Association saw itself as firmly part of the evangelical party of the Church of England and prominent within it were J C Ryle and the 7th Earl of Shaftesbury. The rise of ritualism and liberalism saw evangelicals feeling under pressure and they responded in different ways. Some left but remained Anglican in outlook. The Free Church of England was established for this reason, as was Lightbowne Evangelical Church in Manchester for which Church Society are still the Trustees. Others became non-conformists. The issues today may be different but people are responding in similar ways in England with a number of ex-Anglicans now ‘on the edge’. -

The Benefice Network Sunday Services

261-Benfice Mag 10.qxp_text page 23/03/2020 09:17 Page 2 Sunday Services St George, Fordington, Dorchester, DT1 1LB St Simon & St Jude, Winterborne Monkton, DT2 9PT Every Sun 8am Holy Communion (said) 1st Sun 11.15am Holy Communion 1st, 3rd, 4th, St Martin, Winterborne St Martin, DT2 9JR and 5th Sun 9.45am Holy Communion (sung) 2nd Sun 9.45am All Age Communion (sung) 2nd Sun 8am Holy Communion (BCP) 1st, 3rd, and 4th Sun 11am Holy Communion St Mary the Virgin, Dorchester, DT1 2HL Every Sun 8am Holy Eucharist (said) St Mary, Winterbourne Abbas, DT2 9LP Every Sun 9.45am Holy Eucharist (sung) 1st, 3rd Sun 10am Holy Communion 5th Sun 9.45am Eucharist for Healing 1st Sun 6pm Taize Service St Michael, Winterbourne Steepleton, DT2 9LG 2nd Sun 11am Holy Communion St Peter, Dorchester, DT1 1XA Every Sun 9am Holy Communion (BCP) St Thomas a Beckett, Compton Valence, DT2 9ER Every Sun 10.30am Sung Eucharist 2nd Sun 9.30am Holy Communion St Andrew, West Stafford, DT2 8AB 1st Sun 11.15am Said Holy Communion 2nd and 4th Sun 11.15am Sung Holy Communion For mid-week services and more information 3rd Sun As we 11.15amgoplaced to press Said on Mattins various– Services activities have been most cancelled of which andabouthave restrictions worshipbeen cancelledsee church have pages. been 5th Sun No Service The Benefice Network Office Secretary St Andrew June Jenkins 250719 St Mary [email protected] Verger Cynthia Fry 573076 Organist Benefice Website Organist Geoff Greenhough 267723 Flowers Jill Shepherd 264222 www.dorchesteranglican.info - Flowers -

Forms of Address for Clergy the Correct Forms of Address for All Orders of the Anglican Ministry Are As Follows

Forms of Address for Clergy The correct forms of address for all Orders of the Anglican Ministry are as follows: Archbishops In the Canadian Anglican Church there are 4 Ecclesiastical Provinces each headed by an Archbishop. All Archbishops are Metropolitans of an Ecclesiastical Province, but Archbishops of their own Diocese. Use "Metropolitan of Ontario" if your business concerns the Ecclesiastical Province, or "Archbishop of [Diocese]" if your business concerns the Diocese. The Primate of the Anglican Church of Canada is also an Archbishop. The Primate is addressed as The Most Reverend Linda Nicholls, Primate, Anglican Church of Canada. 1. Verbal: "Your Grace" or "Archbishop Germond" 2. Letter: Your Grace or Dear Archbishop Germond 3. Envelope: The Most Reverend Anne Germond, Metropolitan of Ontario Archbishop of Algoma Bishops 1. Verbal: "Bishop Asbil" 2. Letter: Dear Bishop Asbil 3. Envelope: The Right Reverend Andrew J. Asbil Bishop of Toronto In the Diocese of Toronto there are Area Bishops (four other than the Diocesan); envelopes should be addressed: The Rt. Rev. Riscylla Shaw [for example] Area Bishop of Trent Durham [Area] in the Diocese of Toronto Deans In each Diocese in the Anglican Church of Canada there is one Cathedral and one Dean. 1. Verbal: "Dean Vail" or “Mr. Dean” 2. Letter: Dear Dean Vail or Dear Mr. Dean 3. Envelope: The Very Reverend Stephen Vail, Dean of Toronto In the Diocese of Toronto the Dean is also the Rector of the Cathedral. Envelope: The Very Reverend Stephen Vail, Dean and Rector St. James Cathedral Archdeacons Canons 1. Verbal: "Archdeacon Smith" 1. Verbal: "Canon Smith" 2. -

Mark Wroe Named Next Bishop of Berwick

INSIDE: November 2020 Page 3 Fighting child poverty Page 4 Poms poms everywhere! Page 5 A service for our pets! Page 6 Councils support our churches Page 7&8 2020 Ordinations Page 9 Bishop Mark welcomed to Chester Mark Wroe named next Bishop of Berwick HE Venerable Mark Wroe, first Bishop of Berwick since 1572 across our region concerned for mility and courage.” currently Archdeacon of when he was appointed in 2016. The Venerable Mark Wroe said: loved ones and livelihoods, yet the Northumberland, is the “It’s an extraordinary privilege to Church has such deep hope and Mark will be ordained and con- next Suffragan Bishop of Mark’s appointment was an- be called to be the next Bishop of joy in Jesus Christ to offer. I look secrated a bishop by the Archbish- BerwickT in the Diocese of Newcas- nounced at Berwick Town Hall by Berwick and to serve God along- forward to working with all those op of York, Stephen Cottrell in a tle. the Bishop of Newcastle, the Right side Bishop Christine in Newcas- in our communities, who seek to service early next year. Reverend Christine Hardman, fol- tle Diocese. I’m very aware that work together for a more compas- He succeeds the Right Reverend lowing confirmation of approval these are challenging and disori- sionate society, and to sharing our ■ For more, go to page 3 or visit Mark Tanner who had been the from the Queen. entating times, with many people hope and faith in Christ with hu- https://bit.ly/3dR0d4i SEE OUR ORDINATIONS PICTURE SPECIAL ON PAGES 7 AND 8 2 generous engaged open Bishop’s Diary November This is not a full list of the Bishop’s engagements but includes the items TOWARDS A we think might be of particular interest to you. -

A Celebration of Ministry with the Enthronement of the Rt Revd Mark Tanner As the 41St Bishop of Chester

A Celebration of Ministry with the Enthronement of The Rt Revd Mark Tanner as the 41st Bishop of Chester Saturday 26th June at 2.00pm 1 Welcome from Tim Stratford, Dean of Chester A very warm welcome to Chester Cathedral on this significant day in the life of the Church of God and Diocese of Chester. It seems to have taken a long time coming. There has been a long process of discernment and selection which led up to the announcement that Bishop Mark Tanner, then Bishop of Berwick, was to be the forty-first and next Bishop of Chester. This included consultations in communities across the diocese and meetings of the Crown Nominations Commission in which the diocese was represented. Following an announcement made by 10 Downing Street, the College of Canons of this Cathedral met and unanimously elected him. Bishop Mark was confirmed as the Bishop of Chester during online proceedings presided over by the Archbishop of York on Wednesday 15th July last year. At the time we were still in the midst of the first coronavirus lockdown. Archbishop Stephen’s own confirmation had only been completed the week before, and he was still unable to move to York from Chelmsford Diocese. During these proceedings Archbishop Stephen laid a charge on Bishop Mark which is included in these pages. Bishop Mark picked up the reins here in Chester following an innovative “Crozier Service” on 20th September that was created to mark the beginning of his ministry in these unusual times. He was unable formally to occupy the Bishop’s Seat, known as the Cathedra, in the Cathedral Quire until paying homage to Her Majesty the Queen. -

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2021

PORVOO PRAYER DIARY 2021 The Porvoo Declaration commits the churches which have signed it ‘to share a common life’ and ‘to pray for and with one another’. An important way of doing this is to pray through the year for the Porvoo churches and their Dioceses. The Prayer Diary is a list of Porvoo Communion Dioceses or churches covering each Sunday of the year, mindful of the many calls upon compilers of intercessions, and the environmental and production costs of printing a more elaborate list. Those using the calendar are invited to choose one day each week on which they will pray for the Porvoo churches. It is hoped that individuals and parishes, cathedrals and religious orders will make use of the Calendar in their own cycle of prayer week by week. In addition to the churches which have approved the Porvoo Declaration, we continue to pray for churches with observer status. Observers attend all the meetings held under the Agreement. The Calendar may be freely copied or emailed for wider circulation. The Prayer Diary is updated once a year. For corrections and updates, please contact Ecumenical Officer, Maria Bergstrand, Ms., Stockholm Diocese, Church of Sweden, E-mail: [email protected] JANUARY 3/1 Church of England: Diocese of London, Bishop Sarah Mullally, Bishop Graham Tomlin, Bishop Pete Broadbent, Bishop Rob Wickham, Bishop Jonathan Baker, Bishop Ric Thorpe, Bishop Joanne Grenfell. Church of Norway: Diocese of Nidaros/ New see and Trondheim, Presiding Bishop Olav Fykse Tveit, Bishop Herborg Oline Finnset 10/1 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Oulu, Bishop Jukka Keskitalo Church of Norway: Diocese of Sør-Hålogaland (Bodø), Bishop Ann-Helen Fjeldstad Jusnes Church of England: Diocese of Coventry, Bishop Christopher Cocksworth, Bishop John Stroyan. -

“Beyond the Character of the Times”: Anglican Revivalists in Eighteenth-Century Virginia

“Beyond the Character of the Times”: Anglican Revivalists in Eighteenth-Century Virginia By Frances Watson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Liberty University 2021 Table of Contents Introduction 2 Chapter One: Beyond Evangelical – Anglican Revivalists 14 Chapter Two: Beyond Tolerant – Spreading Evangelicalism 34 Chapter Three: Beyond Patriotic – Proponents of Liberty 55 Conclusion 69 Bibliography 77 ~ 1 ~ Introduction While preaching Devereux Jarratt’s funeral service, Francis Asbury described him thus: “He was a faithful and successful preacher. He had witnessed four or five periodical revivals of religion in his parish. When he began his labours, there was no other, that he knew of, evangelical minister in all the province!”1 However, at the time of his death, Jarratt would be one of a growing number of Evangelical Anglican ministers in the province of Virginia. Although Anglicanism remained the established church for the first twenty three years of Jarratt’s ministry, the Great Awakening forcefully brought the message of Evangelicalism to the colonies. As the American Revolution neared, new ideas about political and religious freedom arose, and Evangelical dissenters continued to grow in numbers. Into this scene stepped Jarratt, his friend Archibald McRobert, and his student Charles Clay. These three men would distinguish themselves from other Anglican clergymen by emulating the characteristics of the Great Awakening in their ministries, showing tolerance in their relationships with other religious groups, and providing support for American freedoms. Devereux Jarratt, Archibald McRobert, and Charles Clay all lived and mainly ministered to communities in the Piedmont area. -

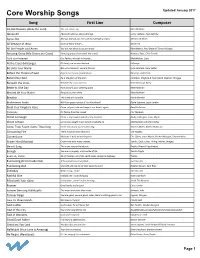

Core Worship Songs Updated January 2017 Song First Line Composer

Core Worship Songs Updated January 2017 Song First Line Composer 10,000 Reasons (Bless the Lord) The sun comes up, Matt Redman Above All Above all nations, above all kings Lenny LeBlanc, Paul Baloche Agnus Dei Alleluia, alleluia, for the Lord God Almighty reigns Michael W Smith All because of Jesus Giver of every breath… Steve Fee All the People said Amen You are not alone if you are lonely Matt Maher, Paul Moak & Trevor Morgan Amazing Grace (My Chains are Gone) Amazing grace, how sweet the sound Newton, Rees, Chris Tomlin As it is in heaven Our Father, who art in heaven… Matt Maher, Cash At the Cross (Hillsongs) Oh Lord, you've searched me Hillsongs Be Unto Your Name We are a moment, you are forever Lynn DeShazo, Gary Sadler Before the Throne of God Before the throne of God above Bancroft, Vicki Cook Behold Our God He is the glory of the stars Jonathan, Meghan & Ryan Baird, Stephen Altrogge Beneath the Cross Beneath the cross of Jesus Keith & Kristyn Getty Better Is One Day How lovely is your dwelling place Matt Redman Blessed Be Your Name Blessed be your name Matt Redman Breathe This is the air I breathe Marie Barnett Brokenness Aside Will Your grace run out if I let You down? David Leonard, Leslie Jordan Build Your Kingdom Here Come set your rule and reign in our hearts again Rend Collective Cannons It's falling from the clouds Phil Wyckam Christ is Enough Christ is my reward and all of my devotion Reuben Morgan, Jonas Myrin Christ is Risen Let no one caught in sin remain insidethe lie Matt Maher and Mia Fieldes Come Thou Fount, Come