Urban Redevelopment: from Urban Squalor to Global City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Clinics in Downtown Core Open on Friday 24 Jan 2020

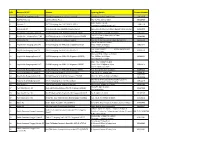

LIST OF CLINICS IN DOWNTOWN CORE OPEN ON FRIDAY 24 JAN 2020 POSTAL S/N NAME OF CLINIC BLOCK STREET NAME LEVEL UNIT BUILDING TEL OPENING HOURS CODE 1 ACUMED MEDICAL GROUP 16 COLLYER QUAY 02 03 INCOME AT RAFFLES 049318 65327766 8.30AM-12.30PM 2 AQUILA MEDICAL 160 ROBINSON ROAD 05 01 SINGAPORE BUSINESS FEDERATION CENTER 068914 69572826 11.00AM- 8.00PM 3 AYE METTA CLINIC PTE. LTD. 111 NORTH BRIDGE ROAD 04 36A PENINSULA PLAZA 179098 63370504 2.30PM-7.00PM 4 CAPITAL MEDICAL CENTRE 111 NORTH BRIDGE ROAD 05 18 PENINSULA PLAZA 179098 63335144 4.00PM-6.30PM 5 CITYHEALTH CLINIC & SURGERY 152 BEACH ROAD 03 08 GATEWAY EAST 189721 62995398 8.30AM-12.00PM 6 CITYMED HEALTH ASSOCIATES PTE LTD 19 KEPPEL RD 01 01 JIT POH BUILDING 089058 62262636 9.00AM-12.30PM 7 CLIFFORD DISPENSARY PTE LTD 77 ROBINSON ROAD 06 02 ROBINSON 77 068896 65350371 9.00AM-1.00PM 8 DA CLINIC @ ANSON 10 ANSON ROAD 01 12 INTERNATIONAL PLAZA 079903 65918668 9.00AM-12.00PM 9 DRS SINGH & PARTNERS, RAFFLES CITY MEDICAL CENTRE 252 NORTH BRIDGE RD 02 16 RAFFLES CITY SHOPPING CENTRE 179103 63388883 9.00AM-12.30PM 10 DRS THOMPSON & THOMSON RADLINK MEDICARE 24 RAFFLES PLACE 02 08 CLIFFORD CENTRE 048621 65325376 8.30AM-12.30PM 11 DRS. BAIN + PARTNERS 1 RAFFLES QUAY 09 03 ONE RAFFLES QUAY - NORTH TOWER 048583 65325522 9.00AM-11.00AM 12 DTAP @ DUO MEDICAL CLINIC 7 FRASER STREET B3 17/18 DUO GALLERIA 189356 69261678 9.00AM-3.00PM 13 DTAP @ RAFFLES PLACE 20 CECIL STREET 02 01 PLUS 049705 69261678 8.00AM-3.00PM 14 FULLERTON HEALTH @ OFC 10 COLLYER QUAY 03 08/09 OCEAN FINANCIAL CENTRE 049315 63333636 -

Statistics Singapore Newsletter, September 2011

The Elderly in Singapore By Miss Wong Yuet Mei and Mr Teo Zhiwei Income, Expenditure and Population Statistics Division Singapore Department of Statistics Introduction Basic profiles such as: • age With better nutrition, advancement • sex in medical science and an increased • type of dwelling awareness of the importance of a • geographical distribution healthy lifestyle, the life expectancy of were compiled using administrative the Singapore resident population has records from multiple sources. improved over the years. Detailed profiles such as: On average, a new-born resident could • marital status expect to live to age 82 years in 2010. • education The life expectancy at birth was lower at • language most frequently spoken 75 years in 1990. at home • living arrangement For the average elderly person in • mobility status Singapore, life expectancy at age 65 • main source of financial support years rose from 16 years in 1990 to 20 years in 2010. Compared to 1990, there were obtained from the Census 2010 are more elderly persons aged 65 years sample enumeration of households staying and over today. in residential housing, and thus excluded those living in institutions such as old This article provides a statistical profile age or nursing homes. The resident of the elderly resident population aged population comprises Singapore citizens 65 years and over in Singapore. and permanent residents. Copyright © Singapore Department of Statistics. All rights reserved. Statistics Singapore Newsletter September 2011 Size of Elderly Resident Geographical Distribution Population Of the 352,600 elderly residents in 2011, Of the 3.79 million Singapore residents 56 per cent were concentrated in ten as at end-June 2011, 352,600 residents planning areas1. -

From Colonial Segregation to Postcolonial ‘Integration’ – Constructing Ethnic Difference Through Singapore’S Little India and the Singapore ‘Indian’

FROM COLONIAL SEGREGATION TO POSTCOLONIAL ‘INTEGRATION’ – CONSTRUCTING ETHNIC DIFFERENCE THROUGH SINGAPORE’S LITTLE INDIA AND THE SINGAPORE ‘INDIAN’ ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy IN THE UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY BY SUBRAMANIAM AIYER UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY 2006 ---------- Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 3 Thesis Argument 3 Research Methodology and Fieldwork Experiences 6 Theoretical Perspectives 16 Social Production of Space and Social Construction of Space 16 Hegemony 18 Thesis Structure 30 PART I - SEGREGATION, ‘RACE’ AND THE COLONIAL CITY Chapter 1 COLONIAL ORIGINS TO NATION STATE – A PREVIEW 34 1.1 Singapore – The Colonial City 34 1.1.1 History and Politics 34 1.1.2 Society 38 1.1.3 Urban Political Economy 39 1.2 Singapore – The Nation State 44 1.3 Conclusion 47 2 INDIAN MIGRATION 49 2.1 Indian migration to the British colonies, including Southeast Asia 49 2.2 Indian Migration to Singapore 51 2.3 Gathering Grounds of Early Indian Migrants in Singapore 59 2.4 The Ethnic Signification of Little India 63 2.5 Conclusion 65 3 THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE COLONIAL NARRATIVE IN SINGAPORE – AN IDEOLOGY OF RACIAL ZONING AND SEGREGATION 67 3.1 The Construction of the Colonial Narrative in Singapore 67 3.2 Racial Zoning and Segregation 71 3.3 Street Naming 79 3.4 Urban built forms 84 3.5 Conclusion 85 PART II - ‘INTEGRATION’, ‘RACE’ AND ETHNICITY IN THE NATION STATE Chapter -

Past, Present and Future: Conserving the Nation’S Built Heritage 410062 789811 9

Past, Present and Future: Conserving the Nation’s Built Heritage Today, Singapore stands out for its unique urban landscape: historic districts, buildings and refurbished shophouses blend seamlessly with modern buildings and majestic skyscrapers. STUDIES URBAN SYSTEMS This startling transformation was no accident, but the combined efforts of many dedicated individuals from the public and private sectors in the conservation-restoration of our built heritage. Past, Present and Future: Conserving the Nation’s Built Heritage brings to life Singapore’s urban governance and planning story. In this Urban Systems Study, readers will learn how conservation of Singapore’s unique built environment evolved to become an integral part of urban planning. It also examines how the public sector guided conservation efforts, so that building conservation could evolve in step with pragmatism and market considerations Heritage Built the Nation’s Present and Future: Conserving Past, to ensure its sustainability through the years. Past, Present “ Singapore’s distinctive buildings reflect the development of a nation that has come of age. This publication is timely, as we mark and Future: 30 years since we gazetted the first historic districts and buildings. A larger audience needs to learn more of the background story Conserving of how the public and private sectors have creatively worked together to make building conservation viable and how these efforts have ensured that Singapore’s historic districts remain the Nation’s vibrant, relevant and authentic for locals and tourists alike, thus leaving a lasting legacy for future generations.” Built Heritage Mrs Koh-Lim Wen Gin, Former Chief Planner and Deputy CEO of URA. -

Singapore-Office-Q2-2020-7406.Pdf

Overall occupancy levels are expected to come under increasing“ pressure for the rest “ of the year and could decline by 5% or more in 2020. CALVIN YEO, HEAD, CORPORATE REAL ESTATE Singapore Research Office Q2 2020 MARKET SNAPSHOT MILLION SQFT 5.15 knightfrank.com.sg/research EXPECTED ISLAND-WIDE THE ECONOMIC FALLOUT FROM NEW SUPPLY (Q2 2020-2023) (5.2% VACANCY) THE PANDEMIC WEIGHED DOWN CBD94.8% OCCUPANCY ON DEMAND AND RENTS PSF PM OVERALLS$10.61 PRIME OFFICE RENTS Rents and Occupancy Prime Grade office rents in the Raffles Exhibit 1: Selected Upcoming Office Supply in the Central Business Place/Marina Bay precinct dropped District PROJECT STREET PLANNING TOTAL OFFICE DEVELOPER for the second consecutive quarter in NAME NAME AREA SPACE GFA (SQ FT) Q2 2020, declining by a further 4.1% Robinson Afro-Asia I-Mark Robinson Road Downtown Core 180,400 Development quarter-on-quarter (q-o-q) to S$10.61 Pte Ltd per square foot per month (psf pm) as Total Key 180,400 Supply 2020 landlords lowered their expectations to CL Office Trustee maintain occupancy and try to secure CapitaSpring Market Street Downtown Core 754,550 Pte Ltd / Glory SR Trustee Pte Ltd new tenants amid clouded economic Hub Synergy (S) Hub Synergy Point Anson Road Downtown Core 154,350 prospects for the rest of the year, but Pte Ltd occupancy rates remained relatively CapitaLand Commercial 21 Collyer Quay Collyer Quay Downtown Core 200,000 stable decreasing by a marginal 0.2% Management Pte Ltd q-o-q in the precinct due to ongoing Total Key 1,108,900 lease commitments. -

S/N Name of RC/CC Address Opening Details Contact Number

S/N Name of RC/CC Address Opening Details Contact Number 1 Acacia RC @ Sengkang South Blk 698C Hougang St 52, #01-29, S533698 Monday to Friday, 2pm to 4pm 63857948 2 ACE The Place CC 120 Woodlands Ave 1 Mon to Thu, 9am to 10pm 68913430 Mon, Thurs, Fri & Sat, 3 Aljunied CC Blk 110 Hougang Ave 1 #01-1048 S530110 62885578 2.00pm to 10.00pm (except PH) 4 Anchorvale CC 59 Anchorvale Road S544965, Reading Corner Open daily, 9.30am to 9.30pm (Except Public Holiday) 64894959 5 Ang Mo Kio - Hougang Zone 1 RC Blk 601 Hougang Ave1 #01-101 Singapore 530601 Tue, Thu and Fri, 1.00 pm to 5.30pm 62855065 Tue to Fri, 1pm to 6pm, 8pm to 10pm 6 Ang Mo Kio – Hougang Zone 7 RC Blk 976 Hougang Street 91 #01-252 Singapore 530976 63644064 Sat, 1pm to 6pm 7 Ang Mo Kio CC 795 Ang Mo Kio Ave 1 Singapore 569976 Monday to Sunday, 9am to 10pm (Except PH) 64566536 Tue & Thu, 1pm to 9.30pm 8 Ang Mo Kio- Hougang Zone 2 RC Blk 623 Hougang Ave 8 #01-242 Singapore 530623 Wed, 7.30pm to 9.30pm 63824344 Fri & Sat, 9am to 5.30pm Tue : 11pm to 6pm Friday, 11pm to 5pm 9 Ang Mo Kio-Hougang Zone 3 RC Blk 643 Hougang Ave 8 #01-285 (S)530643 86849568 Sat 9am to 5pm Mon and Wed, 1.00pm to 5.00pm 10 Ang Mo Kio-Hougang Zone 4 RC Blk 658 Hougang Ave 8 #01-435 Singapore (530658) Thu, 10.30am to 1.00pm 83549021 Sat, 9.00am to 12.00pm Mon – Tue 8.30am to 6pm 11 Ang Mo Kio-Hougang Zone 5 RC Blk 669 Hougang Ave 8 #01-737 Singapore 530669 Wed – Thur 12.30pm to 10pm 63851475 Sun-11.30am to 8.30pm 12 Ang Mo Kio-Hougang Zone 6 RC Blk 951 Hougang Ave 9 #01-504 Singapore 530951 Tue, Wed & Thu, -

Ri (A) & Registered Inspectors

REGISTER OF REGISTERED INSPECTORS (ARCHITECTURAL) – RI (A) & REGISTERED INSPECTORS (MECHANICAL & ELECTRICAL) – RI (M&E) EMAIL DISCIPLINE S/NO NAME RI NO ADDRESS/CONTACT TEL FAX (A/M&E) 3 Harbour Front Place #03-01 96327179 1. ABDUL JALIL KADIR MYDIN A 411 Harbour Front Tower Two [email protected] Singapore 099254 299A Compassvale Street #13-136 98785274 2. ANG ENG CHUAN, ROY M&E 386 [email protected] Singapore 541299 M/S AEDAS Pte Ltd 11 North Buona Vista Drive #12-07 3. ANG KONG SIONG TONY A 138 96172833 67346233 [email protected] The Metropolis Tower 2 Singapore 138589 116A Jalan Pari Burong 98192112 4. AW SOON SENG JAMES M&E 174 [email protected] Singapore 488759 64456248 M/S K L Au & Associates 33 Ubi Ave 1 #06-46 5. AU KOW LIONG M&E 110 97380020 67427366 [email protected] Vertex Singapore 408868 410H Pasir Panjang Road 6. BOEY WENG CHEONG NICOLASIAN M&E 339 90618230 [email protected] Singapore 117613 C/O VIVATA Pte Ltd 33 Ubi Avenue 3 #05-38/39 7. BENGER DARREN PETER A 353 64532212 64531121 [email protected] Vertex Building Tower A Singapore 408868 M/S Chan Han Chong Consulting Engineers 32 Ang Mo Kio Industrial Park 2 #03-14 97336335 8. CHAN HAN CHONG M&E 175 64817588 [email protected] Sing Industrial Complex 64820282 Singapore 569510 3791 Jalan Bukit Merah #05-12 62722250 9. CHAN KAR WAI A 211 E-Centre @ Redhill 62705833 [email protected] 97610448 Singapore 159471 403 Sin Min Avenue #10-301 10. -

Master Developer Projects in Singapore: Lessons from Suntec City and Marina Bay Financial Centre

IN THIS EDITION Singapore occasionally sells large chunks of government land to master developers for achieving important national planning and development objectives. This article examines the use of this approach for landmark developments such as Suntec City and the Marina Bay Financial Centre, and what lessons they offer for future master development projects. The site of Suntec City was sold in 1988 to a master developer to build a 339,000 sqm GFA integrated international exhibition and convention centre with the prime objective of positioning Singapore as an international exhibition and convention hub. Source: Erwin Soo CC BY-SA 2.0 https://flic.kr/p/fMWVLT Master Developer Projects in Singapore: Lessons from Suntec City and Marina Bay Financial Centre INTRODUCTION be offered, allowing the GLS programme built by master developers, such as Suntec to achieve greater diversity in terms of City and the Marina Bay Financial Centre Under the Government Land Sales (GLS) location and design. (MBFC), which seek to achieve certain Programme1 administered by the Urban planning and developmental objectives. Redevelopment Authority (URA), state Historically, individual land parcels for The 11.7 ha Suntec City site was sold land is sold to private developers for “white” site developments – which can in 1988 to a master developer to build a development. When planning sites for sale, be used to build any mix of residential, 339,000 sqm GFA integrated international URA and the Housing & Development commercial or hotel properties – have been exhibition and convention centre with the Board (HDB), the two main GLS sale kept below 160,000 sqm Gross Floor prime objective of positioning Singapore as agents, tend to plan around certain parcel Area (GFA). -

HOUSING ANG MO KIO Bidadari TECK GHEE

CASHEW SERANGOON NORTH N TAVISTOCK HOUGANG TAMPINES NORTH HOUSING ANG MO KIO Bidadari TECK GHEE A N G HILLVIEW BRIGHT HILL M E O V K A R I O G DEFU D N B I R G I A M S N SIN D H V I L A E M KOVAN L N BUKIT GOMBAK I N U HONGKAH H N I E T S S TENGAH PLANTATION H T 1 G I 2 R 2 Kampong Bugis B TAMPINES EAST TAMPINES B I S H A N UPPER THOMSONU S P T P TENGAH PARK 1 4 N T I P H M I O M M E BISHAN LORONG CHUAN S P D O SERANGOON N A B N - I N L I A S BUKIT BATOK S L O P A J 2 1 H J R T A N S A R N MARYMOUNT N D A N L H R I S S B A T A O B E D H Holland Plain N I S H S A X N S I T R D E E A T B BUKIT BATOK WEST N P I 1 1 A R K R B E U R TAMPINES WEST K S BARTLEY B I R A D D E L L B T S R O A D A O O R A D W T R L E Y A C BEAUTY WORLD CHINESE GARDEN E Y R I V D D D H A Y O A R E H I O N O A T K R R Y TOH GUAN O L A R U L P W A BRADDELL O P R O S A N U E O E N V WOODLEIGH P E R U P O S S A G A N O T L E - 6 I O D E N T J 1 O R A H O U CALDECOTT G O A R G A R N G N T D N A T P N P I R R E A E O R E B A I D O P D X S TAI SENG D R U Y I KING ALBERT PARK N E R A E O A O E R U B R O R KAKI BUKIT U N E L N BEDOK NORTH K H I R P T O N D O P T A I M D L S A U D H L R A A D I A O O JURONG EAST A TOA PAYOH R N D NA K O R O S R L E R POTONG PASIR H J T D P C P A A U I SIXTH AVENUE A M TANAH MERAH N N Dakota Crescent N T O - I 2 I N R E E S E V UBI E A D I L MATTAR B M C U M E A MOUNT PLEASANT E A L U R N B A D D JURONG TOWN HALL P R C N D E X L Y E E N E A A S D W T S S V I E R MACPHERSON J A O R A TAN KAH KEE Y R A Y L H S W A E O S T E S L A P R N X M X -

Official Opening Ceremony for the Jetty/Tower and Suspension Footbridge

; l Sent by : MITA Duty Officer To: cc: (bee: James KOH/MTI/SINGOV) Subject: (Embargoed) Speech by Mr Koo Tsai Kee, 4 Aug 98, 7.00pm Singapore Government PRESS RELEASE Media Division, Ministry of Information and the Arts, #36-00 PSA Building, 460 Alexandra Road, Singapore 119963 . Tel: 3757794/5 --------- EMBARGO INSTRUCTIONS The attached press release/speech is EMBARGOED UNTIL AFTER DELIVERY. Please check against delivery. For assistance call 3757795 SPRinter 3.0, Singapore's Press Releases on the Internet, is located at: http://www.gov.sg/sprinter/ ----------------------------------------------------------- --------- Embargoed Until After Delivery Check Against Delivery SPEECH BY MR KOO TSAI KEE, PARLIAMENTARY SECRETARY FOR NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT, AT THE OFFICIAL OPENING CEREMONY FOR THE JETTY/ TOWER AND SUSPENSION FOOTBRIDGE AT TANJONG RHU ON TUES, 4 AUG 98 AT 7.00 PM AT TANJONG RHU PLACE Good evening, ladies and gentlemen: 1 As we look forward to celebrate 33 years of nationhood in a few days' time, this evening's ceremony is indeed a timely reminder of just 2 how far Singapore has come since independence. This very area we are gathered on was once the site of an old shipyard amid the polluted Geylang River, reminiscent of pre-independence Singapore. 2 But through the combined effort of several government ministries and agencies, working in partnership with the private sector, this same spot is very different today. Indeed, it is a far cry from what it was only six years ago. The shoreline has been reclaimed, the water is cleaner and the stretch of riverside beautifully landscaped. The whole Tanjong Rhu area has been transformed into a quality waterfront residential enclave through the dedicated planning and co-ordination of various government departments. -

List of Approved Hhsc Events As at Mar 16, 2020

LIST OF APPROVED HHSC EVENTS AS AT MAR 16, 2020 License No L/HH/000018/2020 Nature Of Charity auction Event Name Of SingYouth Hub Collection Feb 1, 2020 to Jun 30, 2020 Company/ Period Business/Organis (From - To) ation Name Of - SINGYOUTH HUB Mode(s) Of PayNow for charity auction Beneficiary/ Fund Raising & scan to donate Beneficiaries Approved Wisdom Wall at United Square and auction at the event area (Feb 1, 2020 Location(s) for - Jun 30, 2020) Collection License No L/HH/000478/2019 Nature Of Charity auction Event Name Of Animal Concerns Research Collection Dec 18, 2019 to May 29, Company/ and Education Society Period 2020 Business/Organis (From - To) ation Name Of - ANIMAL CONCERNS Mode(s) Of Placement of donation Beneficiary/ RESEARCH AND EDUCATION Fund Raising boxes Beneficiaries SOCIETY Sale of merchandise Sale of tickets Approved One Farrer Hotel (May 15, 2020 - May 15, 2020) Location(s) for Online ticket sales (Dec 18, 2019 - May 29, 2020) Collection License No L/HH/000023/2020 Nature Of Fun fair Event Name Of BW Monastery Collection Jan 31, 2020 to May 3, 2020 Company/ Period Business/Organis (From - To) ation Name Of - BW MONASTERY Mode(s) Of Placement of donation Beneficiary/ Fund Raising boxes Beneficiaries Sale of merchandise Sale of coupons Approved BW Monastery (Jan 31, 2020 - May 3, 2020) Location(s) for BW Monastery (Geylang Classrooms) (Jan 31, 2020 - May 3, 2020) Collection License No L/HH/000052/2020 Nature Of Tapestry -Festival of Sacred Event Music Name Of THE ESPLANADE CO LTD Collection Apr 16, 2020 to Apr 20, 2020 Company/ Period Business/Organis (From - To) ation Name Of - THE ESPLANADE CO LTD Mode(s) Of Placement of donation Beneficiary/ Fund Raising boxes Beneficiaries Approved The Esplanade - Theatres on the Bay (Apr 16, 2020 - Apr 20, 2020) Location(s) for Collection License No L/HH/000051/2020 Nature Of Donation Drive Event Name Of ENZYME WIZARD ASIA PTE. -

Marina Reservoir for Water Activities

Rules and Regulations for the Use and Storage of Equipment at Kallang Water Sports Centre Marina Reservoir for Water Activities By storing boats and/or equipment at Marina Reservoir and/or the use of Marina Reservoir for water activities, all users do hereby agree to abide by the following rules and regulations in this document. Henceforth, stated as the terms and conditions of this document. 1. BACKGROUND (Terms and Conditions) 1.1 This document states the rules and regulations for all operational procedures mandatory and to be complied with by all organisations/individuals while using the reservoir and/or its facilities as well as the pecuniary charges applicable. 1.2 PUB recognises and approves the Singapore Canoe Federation and its affiliates for the use of the reservoir for canoeing and their various forms of kayaking activities. 1.3 The use of the reservoir is governed by the Public Utilities Board (Reservoir, Catchment Areas and Waterway) Regulations 2006 as well as regulations mandated by the National Parks Board (NParks) for requirements or any statutory provisions, rules, regulations, directives or any guidelines which may be issued from time to time by PUB or any other relevant authority to access the reservoir while carrying out canoeing/kayaking activities. 2 RATIONALE 2.1 The terms and conditions stipulates the use of Marina Reservoir for all water activities and hereby facilitates the safeguard for usage of water provisions as well as the efficient administration pertinent to facility and storage for all Kallang Water Sports Centre users. 2.2 It serves to encourage users to be responsible and civic-minded when using the reservoir for water / land activities.