152909862.Pdf (1.613Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Electoral Data of Taliparamba Assembly Constituency

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/KR-008-0619 ISBN : 978-93-5313-602-4 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 128 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency -(Vidhan Sabha) at a Glance | Features of Assembly 1-2 as per Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency -(Vidhan Sabha) in 2 District | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary 3-9 Constituency -(Lok Sabha) | Town & Village-wise Winner Parties- 2019, 2016, 2014, 2011 and 2009 Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10-11 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Towns and Villages -

SFD Report Kannur India

SFD Report Kannur India Final Report This SFD Report was created through field-based research by Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) as part of the SFD Promotion Initiative Date of production: 29/11/2016 Last update: 29/11/2016 Kannur Executive Summary Produced by: CSE India SFD Report Kannur, India, 2017 Produced by: Suresh Kumar Rohilla, CSE Bhitush Luthra, CSE Anil Yadav, CSE Bhavik Gupta, CSE ©Copyright The tools and methods for SFD production were developed by the SFD Promotion Initiative and are available from: www.sfd.susana.org. All SFD materials are freely available following the open-source concept for capacity development and non-profit use, so long as proper acknowledgement of the source is made when used. Users should always give credit in citations to the original author, source and copyright holder. Last Update: 29/12/2016 I Kannur Executive Summary Produced by: CSE India 1. The graphic 2. Diagram information 3. General city information Desk or field based: Kannur, also known by its English name Cannanore, is a city in Kannur district, state of Comprehensive Kerala, India. It is the administrative headquarters Produced by: of the Kannur district and situated 518 km north of the state capital Thiruvananthapuram. Kannur is Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), New famous for its pristine beaches, Theyyam, (its Delhi native performing art), and its handloom industry. Status: Kannur Municipal Corporation (KMC) is the largest urban local body of the north Malabar region. This is a final SFD On 1st November 2015, the ‘Kannur Municipality’ Date of production: was combined with five adjacent gram panchayats (Pallikkunnu, Puzhathi, Elayavoor, Edakkad & 02/01/2017 Chelora) and became KMC. -

Janakeeya Hotel Updation 07.09.2020

LUNCH LUNCH LUNCH Home No. of Sl. Rural / No Of Parcel By Sponsored by District Name of the LSGD (CDS) Kitchen Name Kitchen Place Initiative Delivery units No. Urban Members Unit LSGI's (Sept 7th ) (Sept 7th ) (Sept 7th) Janakeeya 1 Alappuzha Ala JANATHA Near CSI church, Kodukulanji Rural 5 32 0 0 Hotel Coir Machine Manufacturing Janakeeya 2 Alappuzha Alappuzha North Ruchikoottu Janakiya Bhakshanasala Urban 4 194 0 15 Company Hotel Janakeeya 3 Alappuzha Alappuzha South Samrudhi janakeeya bhakshanashala Pazhaveedu Urban 5 137 220 0 Hotel Janakeeya 4 Alappuzha Ambalappuzha South Patheyam Amayida Rural 5 0 60 5 Hotel Janakeeya 5 Alappuzha Arattupuzha Hanna catering unit JMS hall,arattupuzha Rural 6 112 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 6 Alappuzha Arookutty Ruchi Kombanamuri Rural 5 63 12 10 Hotel Janakeeya 7 Alappuzha Bharanikavu Sasneham Janakeeya Hotel Koyickal chantha Rural 5 73 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 8 Alappuzha Budhanoor sampoorna mooshari parampil building Rural 5 10 0 0 Hotel chengannur market building Janakeeya 9 Alappuzha Chenganoor SRAMADANAM Urban 5 70 0 0 complex Hotel Chennam pallipuram Janakeeya 10 Alappuzha Chennam Pallippuram Friends Rural 3 0 55 0 panchayath Hotel Janakeeya 11 Alappuzha Cheppad Sreebhadra catering unit Choondupalaka junction Rural 3 63 0 0 Hotel Near GOLDEN PALACE Janakeeya 12 Alappuzha Cheriyanad DARSANA Rural 5 110 0 0 AUDITORIUM Hotel Janakeeya 13 Alappuzha Cherthala Municipality NULM canteen Cherthala Municipality Urban 5 90 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 14 Alappuzha Cherthala Municipality Santwanam Ward 10 Urban 5 212 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 15 Alappuzha Cherthala South Kashinandana Cherthala S Rural 10 18 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 16 Alappuzha Chingoli souhridam unit karthikappally l p school Rural 3 163 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 17 Alappuzha Chunakkara Vanitha Canteen Chunakkara Rural 3 0 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 18 Alappuzha Ezhupunna Neethipeedam Eramalloor Rural 8 0 0 4 Hotel Janakeeya 19 Alappuzha Harippad Swad A private Hotel's Kitchen Urban 4 0 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 20 Alappuzha Kainakary Sivakashi Near Panchayath Rural 5 0 0 0 Hotel 43 LUNCH LUNCH LUNCH Home No. -

The Continuing Decline of Hindus in Kerala

The continuing decline of Hindus in Kerala Kerala—like Assam, West Bengal, Purnia and Santhal Pargana region of Bihar and Jharkhand, parts of Western Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand, Mewat of Haryana and Rajasthan, and many of the States in the northeast—has seen a drastic change in its religious demography in the Census period, beginning from 1901. The share of Indian Religionists in Kerala, who are almost all Hindus, has declined from nearly 69 percent in 1901 to 55 percent in 2011, marking a loss of 14 percentage points in 11 decades. Unlike in the other regions mentioned above, in Kerala, both Christians and Muslims have considerable presence and both have gained in their share in this period. Of the loss of 14 percentage points suffered by the Indian Religionists, 9.6 percentage points have accrued to the Muslims and 4.3 to the Christians. Christians had in fact gained 7 percentage points between 1901 and 1961; after that they have lost about 3 percentage points, with the rapid rise in the share of Muslims in the recent decades. This large rise in share of Muslims has taken place even though they are not behind others in literacy, urbanisation or even prosperity. Notwithstanding the fact that they equal others in these parameters, and their absolute rate of growth is fairly low, the gap between their growth and that of others remains very wide. It is wider than, say, in Haryana, where growth rates are high and literacy levels are low. Kerala, thus, proves that imbalance in growth of different communities does not disappear with rising literacy and lowering growth rates, as is fondly believed by many. -

Twenty Years of Home-Based Palliative Care in Malappuram, Kerala, India: a Descriptive Study of Patients and Their Care-Givers

Twenty years of home-based palliative care in Malappuram, Kerala, India: a descriptive study of patients and their care-givers Authors Philip, RR; Philip, S; Tripathy, JP; Manima, A; Venables, E Citation Twenty years of home-based palliative care in Malappuram, Kerala, India: a descriptive study of patients and their care-givers. 2018, 17 (1):26 BMC Palliat Care DOI 10.1186/s12904-018-0278-4 Publisher BioMed Central Journal BMC Palliative Care Rights Archived with thanks to BMC Palliative Care Download date 03/10/2021 01:36:41 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10144/619144 Philip et al. BMC Palliative Care (2018) 17:26 DOI 10.1186/s12904-018-0278-4 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Twenty years of home-based palliative care in Malappuram, Kerala, India: a descriptive study of patients and their care-givers Rekha Rachel Philip1*, Sairu Philip1, Jaya Prasad Tripathy2, Abdulla Manima3 and Emilie Venables4,5 Abstract Background: The well lauded community-based palliative care programme of Kerala, India provides medical and social support, through home-based care, for patients with terminal illness and diseases requiring long-term support. There is, however, limited information on patient characteristics, caregivers and programme performance. This study was carried out to describe: i) the patients enrolled in the programme from 1996 to 2016 and their diagnosis, and ii) the care-giver characteristics and palliative care support from nurses and doctors in a cohort of patients registered during 2013–2015. Methods: A descriptive study was conducted in the oldest community-based palliative clinic in Kerala. Data were collected from annual patient registers from 1996 to 2016 and patient case records during the period 2013–2015. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kasaragod District from 14.02.2021To20.02.2021

Accused Persons arrested in Kasaragod district from 14.02.2021to20.02.2021 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 115/2021 U/s Roopa 4(2)(j) r/w Madhusooda Alinkeel, 20-02-2021 3(a) of Kerala NEELESWA Anil Kumar 42, Vikramkodu House, nan, Sub BAILED BY 1 Raman Perol Village, at 18:15 Epidemic RAM P V Male Kari, Cheruvathur Inspector of POLICE Nileshwaram Hrs Diseases (Kasaragod) Police, NLR Ordinance PS 2020 115/2021 U/s Roopa 4(2)(j) r/w Madhusooda Kunnummal House, Alinkeel, 20-02-2021 3(a) of Kerala NEELESWA 49, nan, Sub BAILED BY 2 Haneefa Muhammed Chayyoth, Kinanoor Perol Village, at 18:15 Epidemic RAM Male Inspector of POLICE Village Nileshwaram Hrs Diseases (Kasaragod) Police, NLR Ordinance PS 2020 56/2021 U/s 143, 147, 283,149 IPC & Kuthirummal 20-02-2021 4(2)(e) r/w 37, House, CHEEMENI BAILED BY 3 prajeesh.K Balan Cheemeni at 11:15 3(b) of Kerala Fayis Ali Male Cheemeni,Kizhakke (Kasaragod) POLICE Hrs Epidemic kkara, cheemeni Diseases Ordinance 2020 56/2021 U/s 143, 147, 283,149 IPC & 20-02-2021 4(2)(e) r/w 30, Paleri Veedu, CHEEMENI BAILED BY 4 Danoop.P. V Krishnan Cheemeni at 11:18 3(b) of Kerala Fayis Ali Male Cheemeni, (Kasaragod) POLICE Hrs Epidemic Diseases Ordinance 2020 56/2021 U/s 143, 147, 283,149 IPC & Nidumba, 20-02-2021 4(2)(e) r/w Prabhakaran. -

Sl.No. Name & Address of Permit Holder Taluk Village Survey No

LIST OF LATERITE BUILDING STONE QUARRIES HAVING MINERAL CONCESSION IN KASARAGOD DISTRICT AS ON 14/09/2018 Permitted Extent Name & address of Quarrying Permit No and date Sl.No. Taluk Village Survey No. Area(In validity permit holder of issue Hectares/Acre s/Ares) A.Krishnnan, S/O.Kelu 01/2017-18 /MM/LS/DOK 1 maniyani,Kundadukkam Hosdurg Panayal 477/1A7 0.24Acre /3897 /M/2017 Dated 19.11.18 ,Ravaneshwarm.P.O. 20.11.17 Abdul Hameed B A S/o 02/2017-18 /MM/LS/DOK 2 Akbar Ali Barikadu KASARGOD Bela 12/5 0.48acre /4040/M/2017 Dated 27.11.18 House Muttathodi 28.11.17 Abdulla Kunhi Madavoor 03/2017-18 /MM/LS/DOK 3 Manzil Badar Masjid KASARGOD Madhur 454/4 0.0971ha /3968/M/2017 Dated 27.11.18 neerchal Kudlu p o 28.11.17 B Abdul Khader ,S/o 04/2017-18 /MM/LS/DOK 4 Bappankutty , zulfa KASARGOD Neerchal 682/1A 0.24Acre /4064/M/2017 Dated 03.12.18 villa, p o Berka,chengala 04.12.17 Hameed H,S/O 05/2017-18 /MM/LS/DOK Hassainar,Pattaramoola 5 KASARGOD Bela 513/1A,513/1C 0.48acre /4066/M/2017 Dated 03.12.18 house,Eriyapady, 04.12.17 Alampadi p o K Narayanan, S/o 06/2017-18 /MM/LS/DOK 6 Kannan C ,Choorikod Hosdurg Panayal 29/2Apt 0.24Acre 02.01.19 /10/M/2018 Dated 03.01.18 house,kolathur p o Nasar P,S/O Moosa P, 07/2017-18 /MM/LS/DOK 7 Pallipuzha house, Bekal Hosdurg Periya 100/pt 0.24Acre 02.01.19 /12/M/2018 Dated 03.01.18 p o,kasargod LIST OF LATERITE BUILDING STONE QUARRIES HAVING MINERAL CONCESSION IN KASARAGOD DISTRICT AS ON 14/09/2018 Permitted Extent Name & address of Quarrying Permit No and date Sl.No. -

Requiring Body SIA Unit

SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT STUDY FINAL REPORT LAND ACQUISITION FOR THE CONSTRUCTION OF OIL DEPOT &APPROACH ROAD FOR HPCL/BPCL AT PAYYANUR VILLAGE IN KANNUR DISTRICT 15th JANUARY 2019 Requiring Body SIA Unit RAJAGIRI outREACH HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM Rajagiri College of Social Sciences CORPORATION LTD. Rajagiri P.O, Kalamassery SOUTHZONE Pin: 683104 Phone no: 0484-2550785, 2911332 www.rajagiri.edu 1 CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 Project and Public Purpose 1.2 Location 1.3 Size and Attributes of Land Acquisition 1.4 Alternatives Considered 1.5 Social Impacts 1.6. Mitigation Measures CHAPTER 2 DETAILED PROJECT DESCRIPTION 2.1. Background of the Project including Developers background 2.2. Rationale for the Project 2.3. Details of Project –Size, Location, Production Targets, Costs and Risks 2.4. Examination of Alternatives 2.5. Phases of the Project Construction 2.6.Core Design Features and Size and Type of Facilities 2.7. Need for Ancillary Infrastructural Facilities 2.8.Work force requirements 2.9. Details of Studies Conducted Earlier 2.10 Applicable Legislations and Policies CHAPTER 3 TEAM COMPOSITION, STUDY APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY 3.1 Details of the Study Team 3.2 Methodology and Tools Used 3.3 Sampling Methodology Used 3.4. Schedule of Consultations with Key Stakeholders 3.5. Limitation of the Study CHAPTER 4 LAND ASSESSMENT 4.1 Entire area of impact under the influence of the project 4.2 Total Land Requirement for the Project 4.3 Present use of any Public Utilized land in the Vicinity of the Project Area 2 4.4 Land Already Purchased, Alienated, Leased and Intended use for Each Plot of Land 4.5. -

Trends in Indian Historiography

HIS2B02 - TRENDS IN INDIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY SEMESTER II Core Course BA HISTORY CBCSSUG (2019) (2019 Admissions Onwards) School of Distance Education University of Calicut HIS2 B02 Trends in Indian Hstoriography University of Calicut School of Distance Education Study Material B.A.HISTORY II SEMESTER CBCSSUG (2019 Admissions Onwards) HIS2B02 TRENDS IN INDIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY Prepared by: Module I & II :Dr. Ancy. M. A Assistant Professor School of Distance Education University of Calicut. Module III & IV : Vivek. A. B Assistant Professor School of Distance Education University of Calicut. Scrutinized by : Dr.V V Haridas, Associate Professor, Dept. of History, University of Calicut. MODULE I Historical Consciousness in Pre-British India Jain and Bhuddhist tradition Condition of Hindu Society before Buddha Buddhism is centered upon the life and teachings of Gautama Buddha, where as Jainism is centered on the life and teachings of Mahavira. Both Buddhism and Jainism believe in the concept of karma as a binding force responsible for the suffering of beings upon earth. One of the common features of Bhuddhism and jainism is the organisation of monastic orders or communities of Monks. Buddhism is a polytheistic religion. Its main goal is to gain enlightenment. Jainism is also polytheistic religion and its goals are based on non-violence and liberation the soul. The Vedic idea of the divine power of speech was developed into the philosophical concept of hymn as the human expression of the etheric vibrations which permeate space and which were first knowable cause of creation itself. Jainism and Buddhism which were instrumental in bringing about lot of changes in the social life and culture of India. -

The Ascent of 'Kerala Model' of Public Health

THE ASCENT OF ‘KERALA MODEL’ OF PUBLIC HEALTH CC. Kartha Kerala Institute of Medical Sciences, Trivandrum, Kerala [email protected] Kerala, a state on the southwestern Coast of India is the best performer in the health sector in the country according to the health index of NITI Aayog, a policy think-tank of the Government of India. Their index, based on 23 indicators such as health outcomes, governance and information, and key inputs and processes, with each domain assigned a weight based on its importance. Clearly, this outcome is the result of investments and strategies of successive governments, in public health care over more than two centuries. The state of Kerala was formed on 1 November 1956, by merging Malayalam-speaking regions of the former states of Travancore-Cochin and Madras. The remarkable progress made by Kerala, particularly in the field of education, health and social transformation is not a phenomenon exclusively post 1956. Even during the pre-independence period, the Travancore, Cochin and Malabar provinces, which merged to give birth to Kerala, have contributed substantially to the overall development of the state. However, these positive changes were mostly confined to the erstwhile princely states of Travancore and Cochin, which covered most of modern day central and southern Kerala. The colonial policies, which isolated British Malabar from Travancore and Cochin, as well as several social and cultural factors adversely affected the general and health care infrastructure developments in the colonial Malabar region. Compared to Madras Presidency, Travancore seems to have paid greater attention to the health of its people. Providing charity to its people through medical relief was regarded as one of the main functions of the state. -

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

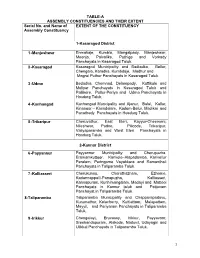

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

Details of Crushers in Kannur District As on the Date of Completion Of

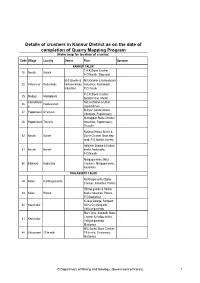

Details of crushers in Kannur District as on the date of completion of Quarry Mapping Program (Refer map for location of crusher) Code Village Locality Owner Firm Operator KANNUR TALUK T.A.K.Stone Crusher , 16 Narath Narath P.O.Narath, Step road M/S Granite & M/S Granite & Hollowbricks 20 Valiyannur Kadankode Holloaw bricks, Industries, Kadankode , industries P.O.Varam P.C.K.Stone Crusher, 25 Madayi Madaippara Balakrishnan, Madai Cherukkunn Natural Stone Crusher, 26 Pookavanam u Jayakrishnan Muliyan Constructions, 27 Pappinisseri Chunkam Chunkam, Pappinissery Muthappan Stone Crusher 28 Pappinisseri Thuruthi Industries, Pappinissery, Thuruthi National Hollow Bricks & 52 Narath Narath Stone Crusher, Near step road, P.O.Narath, Kannur Abhilash Granite & Hollow 53 Narath Narath bricks, Neduvathu, P.O.Narath Maligaparambu Metal 60 Edakkad Kadachira Crushers, Maligaparambu, Kadachira THALASSERY TALUK Karithurparambu Stone 38 Kolari Karithurparambu Crusher, Industries, Porora Hill top granite & Hollow 39 Kolari Porora bricks industries, Porora, P.O.Mattannur K.Jose George, Sampath 40 Keezhallur Stone Crushing unit, Velliyamparambu Mary Jose, Sampath Stone Crusher & Hollow bricks, 41 Keezhallur Velliyamparambu, Mattannur M/S Santhi Stone Crusher, 44 Chavesseri 19 th mile 19 th mile, Chavassery, Mattannur © Department of Mining and Geology, Government of Kerala. 1 Code Village Locality Owner Firm Operator M/S Conical Hollow bricks 45 Chavesseri Parambil industries, Chavassery, Mattannur Jaya Metals, 46 Keezhur Uliyil Choothuvepumpara K.P.Sathar, Blue Diamond Vellayamparamb 47 Keezhallur Granite Industries, u Velliyamparambu M/S Classic Stone Crusher 48 Keezhallur Vellay & Hollow Bricks Industries, Vellayamparambu C.Laxmanan, Uthara Stone 49 Koodali Vellaparambu Crusher, Vellaparambu Fivestar Stone Crusher & Hollow Bricks, 50 Keezhur Keezhurkunnu Keezhurkunnu, Keezhur P.O.