Cincinnati Reds'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The H3 Baseball Bunch

The H3 Baseball Bunch (the picture below is the original 1980 logo) The Baseball Bunch is an American educational children's television series that originally aired in broadcast syndication from August 23, 1980 through the fall of 1985. Produced by Major League Baseball Productions, the series was a 30- minute baseball-themed program airing on Saturday mornings, which featured a combination of comedy sketches and Major League guest-stars, intended to provide instructional tips to Little League aged children. Throughout its five season run, the Emmy Award winning series starred Johnny Bench, Tommy Lasorda and The Famous San Diego Chicken alongside a group of eight children (boys and girls ranging in age from 8–14) as "The Bunch". The Original Baseball Bunch In 2013… (circa 1980) We’re going to re-create the baseball bunch in Charlottesville, and we’ll call it the H3 (HEAD HEART HUSTLE) Baseball Bunch. The participants will be K-3rd graders from the area and they will be paired with 7th-8th grader mentor/”buddies” from our TP Elite Red travel baseball team. Our Version… Kindergarten-3rd Grade • Austin Winslow • Ben Showman Participants • Henry Ford • Tommy Williams • Noah Murray • Dylan Mitchell • Jack McMullan • Zeb Mitchell • Ben Winslow • Ty Enoch • Owen Burton • Lucas Osada • Cole Baglio • Andy Commins • Carter Boyd • Grey Kallen • Spicer Edmunds • Charlie Pausic • Tyler Williams • Dillon O'Connor • Max Moore • Shawn Feggans • Izzy Sanok • Kason Kuhn • Nathan Gragg Benefits to K-3rd Grade Participants • Have lots of fun in a safe environment -

WAYC Hoiberg

PAGE 12: SPORTS PRESS & DAKOTAN n SATURDAY, JUNE 6, 2015 PRESS&DAKOTAN Language Barriers Part Of The Enjoyment At Archery Tournaments BY JEREMY HOECK But you know what? Alyssa (and I don’t mean to speak for her) and I didn’t mind one bit. It was DAILY DOSE [email protected] something new for us, and I’m sure it was new for Paul and Merveille. If either Alyssa or I spoke fluent French, the interview could have produced much more, but even without it, the whole incident proved to Opinions “She speaks French, so can you translate it later?” us how unique the World Archery Youth Championships are for Yankton and its residents. That was the question posed at Press & Dakotan summer intern Alyssa Sobotka and I on Friday Over the years at all of these international archery tournaments, I’ve learned that for the most part, from the afternoon as we prepared to interview an archer and coach from Benin (a small African country). you can communicate clearly with someone, no matter what country they’re from. Only a couple times in P&D Sports A group of archers from 3-4 different countries were on the practice round, getting ready for next the last 8-9 years have I approached someone and realized there was no way we would be able to com- Staff on week’s World Archery Youth Championships. We saw the two people from Benin, and thought that would municate. It’s an understandable occurrence, given how many foreign archers our town has welcomed. -

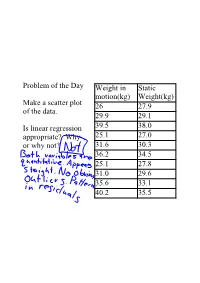

Problem of the Day Make a Scatter Plot of the Data. Is Linear Regression

Problem of the Day Weight in Static motion(kg) Weight(kg) Make a scatter plot 26 27.9 of the data. 29.9 29.1 Is linear regression 39.5 38.0 appropriate? Why 25.1 27.0 or why not? 31.6 30.3 36.2 34.5 25.1 27.8 31.0 29.6 35.6 33.1 40.2 35.5 Salary(in Problem of the Day Player Year millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 Is it appropriate to use George Foster 1982 2.0 linear regression Kirby Puckett 1990 3.0 to predict salary Jose Canseco 1991 4.7 from year? Roger Clemens 1996 5.3 Why or why not? Ken Griffey, Jr 1997 8.5 Albert Belle 1997 11.0 Pedro Martinez 1998 12.5 Mike Piazza 1999 12.5 Mo Vaughn 1999 13.3 Kevin Brown 1999 15.0 Carlos Delgado 2001 17.0 Alex Rodriguez 2001 22.0 Manny Ramirez 2004 22.5 Alex Rodriguez 2005 26.0 Chapter 10 ReExpressing Data: Get It Straight! Linear Regressioneasiest of methods, how can we make our data linear in appearance Can we reexpress data? Change functions or add a function? Can we think about data differently? What is the meaning of the yunits? Why do we need to reexpress? Methods to deal with data that we have learned 1. 2. Goal 1 making data symmetric Goal 2 make spreads more alike(centers are not necessarily alike), less spread out Goal 3(most used) make data appear more linear Goal 4(similar to Goal 3) make the data in a scatter plot more spread out Ladder of Powers(pg 227) Straightening is good, but limited multimodal data cannot be "straightened" multiple models is really the only way to deal with this data Things to Remember we want linear regression because it is easiest (curves are possible, but beyond the scope of our class) don't choose a model based on r or R2 don't go too far from the Ladder of Powers negative values or multimodal data are difficult to reexpress Salary(in Player Year Find an appropriate millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 linear model for the George Foster 1982 2.0 data. -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

Tommy Lasorda

University of Central Florida STARS On Sport and Society Public History 1-9-2021 Tommy LaSorda Richard C. Crepeau University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the Other History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/onsportandsociety University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Public History at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in On Sport and Society by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Crepeau, Richard C., "Tommy LaSorda" (2021). On Sport and Society. 858. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/onsportandsociety/858 SPORT AND SOCIETY FOR H-ARETE – TOMMY LASORDA JANUARY 09, 2021 It was announced today that longtime Dodger manager and even longer fixture and face of the Dodgers has died. In July of 1997 he was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. At that time, I wrote this piece which I send now without alteration. Richard Crepeau SPORT AND SOCIETY FOR ARETE JULY 30, 1997 In a week in which I could choose to talk of Ben Hogan or Don Shula, I find myself compelled towards one of the best-known men in baseball over the past twenty years, Tommy LaSorda, who will be inducted into the manager's wing at Cooperstown on Sunday. Nellie Fox, Phil Niekro, and Willie Wells will also be honored. The fourteenth manager and the fifteenth Dodger honored, this man, who has been considered one of baseball's great ambassadors over the past twenty years, is an overwhelming fan's choice for a spot at Cooperstown. -

Mlb in the Community

LEGENDS IN THE MLB COMMUNITY 2018 A Office of the Commissioner MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL ROBERT D. MANFRED, JR. Commissioner of Baseball Dear Friends and Colleagues: Baseball is fortunate to occupy a special place in our culture, which presents invaluable opportunities to all of us. Major League Baseball’s 2018 Community Affairs Report demonstrates the breadth of our game’s efforts to make a difference for our fans and communities. The 30 Major League Clubs work tirelessly to entertain and to build teams worthy of fan support. Yet their missions go much deeper. Each Club aims to be a model corporate citizen that gives back to its community. Additionally, Major League Baseball is honored to support the important work of core partners such as Boys & Girls Clubs of America, the Jackie Robinson Foundation and Stand Up To Cancer. We are proud to use our platform to lift spirits, to create legacies and to show young people that the magic of our great game is not limited to the field of play. As you will see in the pages that follow, MLB and its Clubs will always strive to make the most of the exceptional moments that we collectively share. Sincerely, Robert D. Manfred, Jr. Commissioner 245 Park Avenue, 31st Floor, New York, NY 10167 (212) 931-7800 LEGENDS Jackie Robinson Day Major League Baseball commemorated the 70th anniversary of the legendary Hall of Famer breaking baseball’s color barrier in 1947 with all players and on-field personnel again wearing Number 42. All home Clubs hosted pregame ceremonies and all games featured Jackie Robinson Day jeweled bases and “70th anniversary of the lineup cards. -

MEDIA INFORMATION Astros.Com

Minute Maid Park 2016 HOUSTON ASTROS 501 Crawford St Houston, TX 77002 713.259.8900 MEDIA INFORMATION astros.com Houston Astros 2016 season review ABOUT THE 2016 RECORD in the standings: The Astros finished 84-78 year of the whiff: The Astros pitching staff set Overall Record: .............................84-78 this season and in 3rd place in the AL West trailing a club record for strikeouts in a season with 1,396, Home Record: ..............................43-38 the Rangers (95-67) and Mariners (86-76)...Houston besting their 2004 campaign (1,282)...the Astros --with Roof Open: .............................6-6 went into the final weekend of the season still alive ranked 2nd in the AL in strikeouts, while the bullpen --with Roof Closed: .......................37-32 in the playoff chase, eventually finishing 5.0 games led the AL with 617, also a club record. --with Roof Open/Closed: .................0-0 back of the 2nd AL Wild Card...this marked the Astros Road Record: ...............................41-40 2nd consecutive winning season, their 1st time to throw that leather: The Astros finished the Series Record (prior to current series): ..23-25-4 Sweeps: ..........................................10-4 post back-to-back winning years since the 2001-06 season leading the AL in fielding percentage with When Scoring 4 or More Runs: ....68-24 seasons. a .987 clip (77 errors in 6,081 total chances)...this When Scoring 3 or Fewer Runs: ..16-54 marked the 2nd-best fielding percentage for the club Shutouts: ..........................................8-8 tale of two seasons: The Astros went 67-50 in a single season, trailing only the 2008 Astros (.989). -

Innovative Lessons from the Miracle Mets of 1969: Part 3 of 3 March 17, 2020 | Written By: Len Ferman

Published in General Innovative Lessons from the Miracle Mets of 1969: Part 3 of 3 March 17, 2020 | Written by: Len Ferman This is the final post in a 3 part series. Read the first two parts: Part 1 | Part 2 How the Worst Team in Baseball History Innovated to Win the World Series 50 Years Ago The New York Mets of 1969 The New York Mets baseball club of 1969 has come to be known as simply the Miracle Mets. The story of that club is perhaps the closest that major league baseball, or for that matter all of professional sports, has ever come to producing a true to life fairy tale. From Worst to First The Mets first season in 1962 was a record setting campaign in futility. The Mets lost 120 of their 160 games. No major league baseball team before or since has come close to losing that many games. And the losing didn’t stop there. From 1962 – 1968 the Mets lost an average of 105 games per year as they finished in last or second to last place every year. Then, in a stunning reversal of fortune, in that miracle year of 1969, when men first landed on the moon, the Mets won 100 games and won the World Series. The Players Credit Their Manager The players on the 1969 Mets all gave the credit for the amazing turnaround to their manager Gil Hodges. “We were managed by an infallible genius[i]”, said Tom Seaver, the club’s young star pitcher. And leading batter on the team, Clean Jones said, “If we had been managed by anybody else, we wouldn’t have won. -

Detroit Tigers Clips Thursday, May 29, 2014

Detroit Tigers Clips Thursday, May 29, 2014 Detroit Free Press Oakland 3, Detroit 1: Tigers closer Joe Nathan unable to finish off Anibal Sanchez's gem (Windsor) Detroit Tigers' Austin Jackson experiencing 'a little bit of a funk' at plate (Windsor) Oakland 3, Detroit 1: Why the Tigers lost Wednesday (Windsor) Miguel Cabrera: The real Yankees Killer? (Staff) Shawn Windsor: Detroit Tigers' skid described as 'weird' and 'seven days from hell' (Windsor) The Detroit News Athletics foil Anibal Sanchez's gem with walk-off victory against Tigers (Gage) Tigers weigh shortstop options Eugenio Suarez, Hernan Perez (Henning) Tigers pitcher Max Scherzer 'more frustrated' with latest outing (Gage) Rookie Nick Castellanos' newfound patience pays off for Tigers (Gage) MLive.com Detroit Tigers need for speed: Ron LeFlore sees similarities 40 years apart (Wallner) Analysis: Joe Nathan, Nick Castellanos contribute to walk-off loss, interesting postgame session (Iott) Detroit Tigers' Rajai Davis day to day after leaving game with left shoulder bruise (Iott) Athletics 3, Tigers 1: Josh Donaldson hits walk-off home run off Joe Nathan (Iott) Brad Ausmus sees no key reason Austin Jackson has struggled: 'He's just in a little bit of a funk' (Iott) Inside the minors: Eugenio Suarez off to hot start in Triple-A; Robbie Ray struggles in return to Toledo (Schmehl) MLB.com Tigers topped late after Anibal's terrific outing (Eymer) Knebel settling in after quick trip up to Majors (Eymer) Tigers, A's both win replay challenges (Eymer) A's aim to hold on to series advantage -

AUCTION ITEMS FSCNY 18 Annual Conference & Exposition May 11

AUCTION ITEMS FSCNY 18th Annual Conference & Exposition May 11, 2010 These items will be available for auction at the Scholarship booth at FSCNY's Conference & Exposition on May 11th. There will be more baseball items added as we get closer to the conference. All proceeds will go to the FSCNY Scholarship Program. Payment can be made by either a check or credit card. Your continued support is greatly appreciated. Sandy Herman Chairman, Scholarship Committee Baseball Robinson Cano Autographed Baseball Bat - Autographed baseball bat of Yankees Robinson Cano. Bucky Dent and Mike Torrez Autographed Framed Photo - A photo of Bucky Dent's homerun over the green monster in 1978, autographed by Bucky Dent and Mike Torrez. Derek Jeter SI Cover/WS Celebration Collage with Plaque - Original 8x10 photo of SI cover with Derek Jeter Sportsman of the year next to original 8x10 photo of Derek Jeter during locker room celebration after World Series win. Derek Jeter Autographed Baseball - Baseball autographed photo of Yankees Derek Jeter. Derek Jeter Autographed 16x20 Framed Photo - Sepia autographed photo of Yankees Derek Jeter tapping the DiMaggio Quote sign that says I want to Thank the Good Lord for Making me a Yankee. It is also signed by the artist. Derek Jeter 20x24 Photo with Dirt from the Stadium (Sliding into 3rd) - Photo of Derek Jeter sliding dirt from the stadium affixed to the photo. Derek Jeter Framed Photo/Ticket/Scorecard Collage (Record Breaking Hit) - This is a photo of Derek Jeter as he set the all time Yankee hit record with framed with a replica of the ticket and scorecard from the game Jerry Koosman, Ed Charles and Jerry Grote Autographed 8x10 Framed Photo - Autographed photo of Jerry Grote, Ed Charles, and Jerry Koosman at the moment the Mets won the 1969 World Series. -

Progressive Team Home Run Leaders of the Washington Nationals, Houston Astros, Los Angeles Angels and New York Yankees

Academic Forum 30 2012-13 Progressive Team Home Run Leaders of the Washington Nationals, Houston Astros, Los Angeles Angels and New York Yankees Fred Worth, Ph.D. Professor of Mathematics Abstract - In this paper, we will look at which players have been the career home run leaders for the Washington Nationals, Houston Astros, Los Angeles Angels and New York Yankees since the beginning of the organizations. Introduction Seven years ago, I published the progressive team home run leaders for the New York Mets and Chicago White Sox. I did similar research on additional teams and decided to publish four of those this year. I find this topic interesting for a variety of reasons. First, I simply enjoy baseball history. Of the four major sports (baseball, football, basketball and cricket), none has had its history so consistently studied, analyzed and mythologized as baseball. Secondly, I find it amusing to come across names of players that are either a vague memory or players I had never heard of before. The Nationals The Montreal Expos, along with the San Diego Padres, Kansas City Royals and Seattle Pilots debuted in 1969, the year that the major leagues introduced division play. The Pilots lasted a single year before becoming the Milwaukee Brewers. The Royals had a good deal of success, but then George Brett retired. Not much has gone well at Kauffman Stadium since. The Padres have been little noticed except for their horrid brown and mustard uniforms. They make up for it a little with their military tribute camouflage uniforms but otherwise carry on with little notice from anyone outside southern California. -

Record Baylor

C8 SPORTS & SCOREBOARD SUNDAY, APRIL 4, 2021 | KILLEEN DAILY HERALD Baseball fans, meanwhile, appeared di- fans who just want to enjoy the game and vided on pulling the game from Georgia. support their team,” she said. “We need BRIEFS MLB Patrick Smith, a lifelong Braves fan in to take politics out of sports.” FROM PAGE C7 Ellisville, Mississippi, said he thinks the But Dick Pagano, a baseball fan in Elk Yordan Álvarez hits 3-run homer league made the right decision and noted Grove Village, Illinois, said he will not as Astros beat A’s again fi l ed a lawsuit over the measure, which that not taking a stand would have polar- watch or attend any games this year. adds greater legislative control over how ized some supporters. “They shot themselves in the foot,” OAKLAND, Calif. — Yordan Álvarez elections are run and includes strict “When governments restrict access said Pagano, who added he will be disap- hit a three-run homer and Houston identifi cation requirements for voting to the ballot box, someone has to step in pointed to miss the planned Hank Aaron kept thriving through all the boos, absentee by mail. to encourage these entities to roll back celebration during the All-Star Game, slugging its way to a third straight Critics say the law will disproportion- those measures,” he said. because he once saw him play in the 1957 win in a 9-1 victory over the Oakland ately affect communities of color. Lorre Sweetman, in Kahului, Hawaii, World Series. Aaron, who played for the Athletics on Saturday.