Biocentrism As a Constituent Element of Modernism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONIST AR-R1 and THOUGH-R1

ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONIST AR-r1 AND THOUGH-r1 AN HONORS THESIS BY CHRISTY DILLARD THESIS ADVISOR DR. MICHAEL PRATER BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, IN DECEMBER 2001 GRADUATION DATE MAY 2002 :.>: .. ,., ABSTRACT This curriculum is designed for upper elementary school students (grades 5/6). Designed as four units, the curriculum explores several ways Abstract Expressionism took shape and form during the 1950's. By engaging themselves in the world of the Abstract Expressionist painters, students will better understand change in the world of art as weLL as in their own artistic and personal growth. Each unit is comprised of four lessons, one each in the content areas of History, Aesthetics, Criticism, and Production. In each lesson, students will apply critical thinking and problem solving skills in both cooperative and individual active learning tasks. A continuous reflective journal will assist students in the structuring and communication of their ideas into words. At the end of the unit, students create two self directed artworks and an artist's statement, reflecting their gathered understanding of this vital period of Art History. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost I would like to thank Dr. Michael Prater for his boundless energy, effort, and care. His assistance has played a very important role in both my success as an individual and my confidence in becoming a future art educator. Thank you to both Jason CateLLier and Heather Berryman for being my Art Education partners through the years. And last but not Least, thank you to Jonathon Moore for his constant patience and positive feedback. - LE OF CONTENTS Rationale Literature Review Paper Curriculum Overview Curriculum Goals Ongoing Journal Description Unit 1- Biomorphism and the Subconscious Unit 2- Spontaneity and the Subconscious Unit 3- Planned Abstraction Unit 4- Colorfield Painting Unit 5 (single lesson)- Pulling it All Together Artist Biographies Index of Illustrations Reference List RATIONALE Abstract Expressionism is one of the most vital movements in art history. -

Yves Tanguy and Surrealism Jonathan Stuhlman

Navigating a Constantly Shifting Terrain: Yves Tanguy and Surrealism Jonathan Stuhlman Charlotte, NC B.A. Bowdoin College, 1996 M.A. School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 1998 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art History and Architecture University of Virginia December, 2013 ______________________________ ______________________________ ______________________________ ______________________________ II © Copyright by Jonathan Stuhlman All Rights Reserved December 2013 III Abstract: Yves Tanguy (1900-1955) was one of the first visual artists to join the Surrealist movement and was considered one of its core members for the majority of his career. He was also a close friend and longtime favorite of the movement’s leader, André Breton. Yet since his death, there has been surprisingly little written about his work that either adds to our understanding of why he remained in favor for so long and how he was able to do so. The aura of impenetrability that his paintings project, along with his consistent silence about them and a paucity of primary documents, has done much to limit the ways in which scholars, critics, and the public have been able (or willing) to engage with his work. As a result, Tanguy has been shuffled to the edges of recent developments in the critical discourse about Surrealism. This dissertation argues against the narrow, limited ways in which Tanguy’s art has been discussed most frequently in the past. Such interpretations, even those penned for exhibition catalogues and monographs supporting his work, have tended to be broad, diffuse, and biographically- and chronologically-driven rather than engaged with the works of art themselves and a critical analysis of the context in which they were created. -

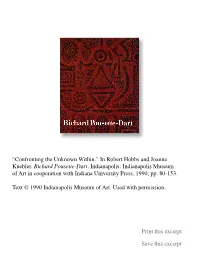

Richard Pousette-Dart

“Confronting the Unknown Within.” In Robert Hobbs and Joanne Kuebler. Richard Pousette-Dart. Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art in cooperation with Indiana University Press, 1990; pp. 80-153. Text © 1990 Indianapolis Museum of Art. Used with permission. Confronting the Richard Pousette-Dart's art testifies to the fecundity to enter a preformulative realm full of possibilities of the unconscious mind. A founding member of but without a predictable outcome. In 1937-38 Unknown Within the New York School that came into being in the he defined painting as "that which cannot be 1940s and was generally known as Abstract Expres preconceived,"• and in subsequent notes and sionism in the 1950s, Pousette-Dart has evolved a lectures he referred to the potential of chaos as a Robert Hobbs complex imagery of unicellular life, religious sym necessary route to creation. Early in his career he bols, and overlapping skeins of color to suggest the marveled that "out of the rich enmesh of chaos un dense interconnected web of forms and ideas that lie folds great order and beauty, suggesting utter beyond the threshold of consciousness. While he simplicity is this labyrinth of all possible truths."5 shares with his fellow Abstract Expressionists He repeatedly questioned the wisdom of bracketing an interest in human values and spiritual truths, aspects of life by imprisoning them in static artistic he goes far beyond most other painters of his forms. "The frames are all futile," he wrote, "to generation in emphasizing creation as a primal act close any life away from the inevitable change and of self-definition. -

Dualism and the Critical Languages of Portraiture Evripidis Altintzoglou

Dualism and the Critical Languages of Portraiture Evripidis Altintzoglou MA, BA (HONS) A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Wolverhampton for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy September 2010 This work or any part thereof has not previously been presented in any form to the University or to any other body whether for the purposes of assessment, publication or for any other purpose (unless otherwise indicated). Save for any express acknowledgements, references and/or bibliographies cited in the work, I confirm that the intellectual content of the work is the result of my own efforts and of no other person. The right of Evripidis Altintzoglou to be identified as author of the work is asserted in accordance with ss.77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. At this date copyright is owned by the author. Signature ………………………………………….. Date ………………………………………………… 1 Abstract This thesis analyzes the philosophical origins of dualism in Western culture in the Classical period in order to examine dualist modes of representation in the history of Western portraiture. Dualism – or the separation of soul and body – takes the form in portraiture of the representation of the head or head and shoulders at the expense of the body, and since its emergence in Classical Greece, has been the major influence on portraiture. In this respect the modern portrait’s commonplace attention to the face rests on the dualist notion that the soul, and therefore the individuality of the subject, rests in the head. Art historical literature on portraiture, however, fails to address the pictorial, cultural and theoretical complications arising from various forms of dualism and their different artistic methodologies, such as that of the physiognomy (the definition of personality through facial characteristics) in the 19th century. -

FRENCH MODERNS: Monet to Matisse, 1850–1950

FRENCH MODERNS: Monet to Matisse, 1850–1950 Claude Monet, Rising Tide at Pourville, Fernand Léger, Composition in Red 1882, Brooklyn Museum and Blue, 1930, Brooklyn Museum TEACHER’S STUDY GUIDE Winter–Spring 2019 Contents Program Information and Goals .......................................................................................................... 2 Background to the Exhibition French Moderns: Monet to Matisse .............................................. 3 Preparing Your Students: Nudes in Art .............................................................................................. 4 Artists’ Backgrounds .............................................................................................................................. 5 Pre- and Post-Visit Activities 1. About the Artists ......................................................................................................................... 8 a. Artist Information Sheet............................................................................................. 10 b. Modern European Art Movements Fact Sheet ....................................................... 11 c. Student Worksheet ...................................................................................................... 12 2. Seascapes .................................................................................................................................... 14 3. Landscapes ................................................................................................................................. -

Surrealist Prints from the Collection of the Museum of Modern Art

Surrealist prints from the collection of the Museum of Modern Art Date 1985 Publisher Fort Worth Art Museum Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1728 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art *- 4 Reading Room MoMA 1460 Surrealist Prints from the Collection of The Museum of Modem Art Surrealist Prints from the Collection of The Museum of Modem Art The Fort Worth Art Museum 1985 yioHA l^Co © 1985 The Board of Trustees, The Fort Worth Art Association. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 85-80727. First printing: 2,000 volumes. This catalogue was produced by the Editor's Office, The Fort Worth Art Museum. Printed by Anchor Press, Fort Worth. Set in Caslon by Fort Worth Linotyping Company, Inc. Cover papers are Vintage Velvet by Monarch Paper Company. Text papers are White Classic Text by Monarch Paper Company. Color separations made by Barron Litho Plate Co., Fort Worth. Designed by Vicki Whistler. Cover: Acrobatsin the Night Garden, 1948, by Joan Miro 3/4X8 Lithograph, printed in color, 21 16'/ in. (55.2 x 41.1 cm.) Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Fund. Frontispiece: Plate, 1936, by Pablo Picasso For La Barre d'appui by Paul Eluard. 7/i& Aquatint, 12 x 8'/a in. (31.6 x 21.7 cm.) Purchase Fund. "Surrealist Prints: Introduction" © 1985 Riva Castleman. Exhibition schedule: The Fort Worth Art Museum, -

Surrealism and Its Legacies in Latin America

BRITISH ACADEMY LECTURE Surrealism and its Legacies in Latin America DAWN ADÈS Fellow of the Academy SURREALISM IN LATIN AMERICA has a history peppered with lacunae, mis- understandings and bad faith, not least in the ways this history has been told; it has also had strong adherents and defenders and some of the movement’s greatest poets and artists, such as Roberto Matta from Chile, who made his career exclusively outside the continent, and César Moro, who has been described as ‘the only person who fully deserves the epithet surrealist in Latin America’.1 Surrealism has played an important but contentious role in the develop- ment of modern Latin American art. The history of the reception of surrealist ideas and practices in Latin America has often been distorted by cultural nationalism and also needs to be disentangled from Magic Realism. Surrealism was nonetheless a potent infl uence or chosen affi liation for many artists and its legacies can still be detected in the work of the con- temporary artists from Latin America who now dominate the international scene. Read at the Academy 27 May 2009. 1 Camilo Fernandez Cozman, ‘La concepción del surrealismo en los ensayos de Westphalen’, in César Moro y el surrealismo en América Latina, ed. Yolanda Westphalen (Lima, 2005), p. 44. See also Jason Wilson, ‘The sole surrealist poet: César Moro (1903–1956)’, in S. M. Hart and D. Wood (eds), Essays on Alfredo Bryce Echenique, Peruvian Literature and Culture (London: 2010), pp. 77–90. César Moro, the pseudonym for Alfredo Quispez Asin, was born in Peru, lived in Paris for eight years from 1925 to 1933, encountered the surrealists in 1928, chose to write in French and published his encantatory celebration of love, ‘Renommée d’amour’, in SASDLR in 1933. -

Roberto Matta's Comeback

Roberto Matta’s Comeback: Hermitage’s Fourth Dimension April 15, 2019 The exhibition “Roberto Matta and the Fourth Dimension” has opened at the General Staff building of the State Hermitage. It is dedicated to the artist that lived not so long ago and never joined any artistic trend. Our museum rediscovers this artist and exposes his connection with St. Petersburg. Photo by Dmitry Sokolov Matta was born in Chile in a family of Spanish and French origin. He later insisted that it happened exactly on November 11, 1911 – 11.11.11. His parents made him get a degree in architecture in Santiago; later he left for Paris, where he found a job at the architect bureau of famous Le Corbusier. The bureau had projects in various countries, including the USSR. While preparing the exhibition, curators Oksana Salamatina (New York) and Dmitry Ozerkov (State Hermitage) ploughed through Matta’s family archive and found a postcard with the Bronze Horseman, allegedly sent from Leningrad in 1936. However, he was not too interested to make a career as an architect. He approached Surrealists and met Salvador Dali, who would later call the Chilean painter the most profound artist of the 20th century. Dali recommended Andre Breton, the then leader of the Surrealist movement, to display Matta’s works at the Surrealist exhibition in 1938. But the Surrealist affair was short-lived too. There came one more connection with St. Petersburg. When in London, Matta learned the ideas of Pyotr Ouspensky, the Russian esoteric philosopher who left St. Petersburg after the Russian revolution. Ouspensky’s book “The Fourth Dimension” says that remote points of space and time can be in junction.