Theatre Archive Project: Interview with Richard Digby

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

J Ohn F. a Ndrews

J OHN F . A NDREWS OBE JOHN F. ANDREWS is an editor, educator, and cultural leader with wide experience as a writer, lecturer, consultant, and event producer. From 1974 to 1984 he enjoyed a decade as Director of Academic Programs at the FOLGER SHAKESPEARE LIBRARY. In that capacity he redesigned and augmented the scope and appeal of SHAKESPEARE QUARTERLY, supervised the Library’s book-publishing operation, and orchestrated a period of dynamic growth in the FOLGER INSTITUTE, a center for advanced studies in the Renaissance whose outreach he extended and whose consortium grew under his guidance from five co-sponsoring universities to twenty-two, with Duke, Georgetown, Johns Hopkins, North Carolina, North Carolina State, Penn, Penn State, Princeton, Rutgers, Virginia, and Yale among the additions. During his time at the Folger, Mr. Andrews also raised more than four million dollars in grant funds and helped organize and promote the library’s multifaceted eight- city touring exhibition, SHAKESPEARE: THE GLOBE AND THE WORLD, which opened in San Francisco in October 1979 and proceeded to popular engagements in Kansas City, Pittsburgh, Dallas, Atlanta, New York, Los Angeles, and Washington. Between 1979 and 1985 Mr. Andrews chaired America’s National Advisory Panel for THE SHAKESPEARE PLAYS, the BBC/TIME-LIFE TELEVISION canon. He then became one of the creative principals for THE SHAKESPEARE HOUR, a fifteen-week, five-play PBS recasting of the original series, with brief documentary segments in each installment to illuminate key themes; these one-hour programs aired in the spring of 1986 with Walter Matthau as host and Morgan Bank and NEH as primary sponsors. -

Text Pages Layout MCBEAN.Indd

Introduction The great photographer Angus McBean has stage performers of this era an enduring power been celebrated over the past fifty years chiefly that carried far beyond the confines of their for his romantic portraiture and playful use of playhouses. surrealism. There is some reason. He iconised Certainly, in a single session with a Yankee Vivien Leigh fully three years before she became Cleopatra in 1945, he transformed the image of Scarlett O’Hara and his most breathtaking image Stratford overnight, conjuring from the Prospero’s was adapted for her first appearance in Gone cell of his small Covent Garden studio the dazzle with the Wind. He lit the touchpaper for Audrey of the West End into the West Midlands. (It is Hepburn’s career when he picked her out of a significant that the then Shakespeare Memorial chorus line and half-buried her in a fake desert Theatre began transferring its productions to advertise sun-lotion. Moreover he so pleased to London shortly afterwards.) In succeeding The Beatles when they came to his studio that seasons, acknowledged since as the Stratford he went on to immortalise them on their first stage’s ‘renaissance’, his black-and-white magic LP cover as four mop-top gods smiling down continued to endow this rebirth with a glamour from a glass Olympus that was actually just a that was crucial in its further rise to not just stairwell in Soho. national but international pre-eminence. However, McBean (the name is pronounced Even as his photographs were created, to rhyme with thane) also revolutionised British McBean’s Shakespeare became ubiquitous. -

Savoring the Classical Tradition in Drama

SAVORING THE CLASSICAL TRADITION IN DRAMA MEMORABLE PRESENTATIONS BY THE SHAKESPEARE GUILD I N P R O U D COLLABORATION WIT H THE NATIONAL ARTS CLUB THE PLAYERS, NEW YORK CITY THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING UNION JIM DALE ♦ Friday, January 24 In the 1950s and ’60s JIM DALE was known primarily as a singer and songwriter, with such hits as Oscar nominee “Georgy Girl” to his credit. Meanwhile he was earning plaudits as a film and television comic, with eleven Carry On features that made him a NATIONAL ARTS CLUB household name in Britain. Next came stage roles like 15 Gramercy Park South Autolycus and Bottom with Laurence Olivier’s National Manhattan Theatre Company, and Fagin in Cameron Mackintosh’s PROGRAM AT 6:00 P.M. Oliver. In 1980 he collected a Tony Award for his title Admission Free, But role in Barnum. Since then he has been nominated for Reservations Requested Tony, Drama Desk, and other honors for his work in such plays as Candide, Comedians, Joe Egg, Me and My Girl, and Scapino. As if those accolades were not enough, he also holds two Grammy Awards and ten Audie Awards as the “voice” of Harry Potter. We look forward to a memorable evening with one of the most versatile performers in entertainment history. RON ROSENBAUM ♦ Monday, March 23 Most widely known for Explaining Hitler, a 1998 best-seller that has been translated into ten languages, RON ROSENBAUM is also the author of The Secret Parts of Fortune, Those Who Forget the Past, and How the End Begins: The Road to a Nuclear World War III. -

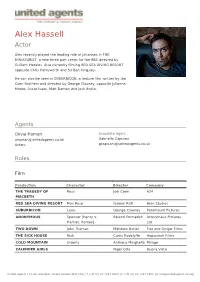

Alex Hassell Actor

Alex Hassell Actor Alex recently played the leading role of Johannes in THE MINIATURIST, a new three part series for the BBC directed by Guillem Morales. Also currently filming RED SEA DIVING RESORT opposite Chris Hemsworth and Sir Ben Kingsley. He can also be seen in SUBURBICON, a feature film written by the Coen Brothers and directed by George Clooney, opposite Julianne Moore, Oscar Isaac, Matt Damon and Josh Brolin. Agents Olivia Homan Associate Agent [email protected] Gabriella Capisani Actors [email protected] Roles Film Production Character Director Company THE TRAGEDY OF Ross Joel Coen A24 MACBETH RED SEA DIVING RESORT Max Rose Gideon Raff Bron Studios SUBURBICON Louis George Clooney Paramount Pictures ANONYMOUS Spencer [Henry V, Roland Emmerich Anonymous Pictures Hamlet, Romeo] Ltd TWO DOWN John Thomas Matthew Butler Fizz and Ginger Films THE SICK HOUSE Nick Curtis Radclyffe Hopscotch Films COLD MOUNTAIN Orderly Anthony Minghella Mirage CALENDER GIRLS Nigel Cole Buena Vista United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Television Production Character Director Company COWBOY BEPOP Vicious Alex Garcia Lopez Netflix THE MINATURIST Johannes Guillem Morales BBC SILENT WITNESS Simon Nick Renton BBC WAY TO GO Phillip Catherine Morshead BBC BIG THUNDER Abel White Rob Bowman ABC LIFE OF CRIME Gary Nash Jim Loach Loc Film Productions HUSTLE Viscount Manley John McKay BBC A COP IN PARIS Piet Nykvist Charlotte Sieling Atlantique Productions -

The Secret Scripture

Presents THE SECRET SCRIPTURE Directed by JIM SHERIDAN/ In cinemas 7 December 2017 Starring ROONEY MARA, VANESSA REDGRAVE, JACK REYNOR, THEO JAMES and ERIC BANA PUBLICITY REQUESTS: Transmission Films / Amy Burgess / +61 2 8333 9000 / [email protected] IMAGES High res images and poster available to download via the DOWNLOAD MEDIA tab at: http://www.transmissionfilms.com.au/films/the-secret-scripture Distributed in Australia by Transmission Films Ingenious Senior Film Fund Voltage Pictures and Ferndale Films present with the participation of Bord Scannán na hÉireann/ the Irish Film Board A Noel Pearson production A Jim Sheridan film Rooney Mara Vanessa Redgrave Jack Reynor Theo James and Eric Bana THE SECRET SCRIPTURE Six-time Academy Award© nominee and acclaimed writer-director Jim Sheridan returns to Irish themes and settings with The Secret Scripture, a feature film based on Sebastian Barry’s Man Booker Prize-winning novel and featuring a stellar international cast featuring Rooney Mara, Vanessa Redgrave, Jack Reynor, Theo James and Eric Bana. Centering on the reminiscences of Rose McNulty, a woman who has spent over fifty years in state institutions, The Secret Scripture is a deeply moving story of love lost and redeemed, against the backdrop of an emerging Irish state in which female sexuality and independence unsettles the colluding patriarchies of church and nationalist politics. Demonstrating Sheridan’s trademark skill with actors, his profound sense of story, and depth of feeling for Irish social history, The Secret Scripture marks a return to personal themes for the writer-director as well as a reunion with producer Noel Pearson, almost a quarter of a century after their breakout success with My Left Foot. -

FILMS and THEIR STARS 1. CK: OW Citizen Kane: Orson Welles 2

FILMS AND THEIR STARS 1. CK: OW Citizen Kane: Orson Welles 2. TGTBATU: CE The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: Clint Eastwood 3. RFTS: KM Reach for the Sky: Kenneth More 4. FG; TH Forest Gump: Tom Hanks 5. TGE: SM/CB The Great Escape: Steve McQueen and Charles Bronson ( OK. I got it wrong!) 6. TS: PN/RR The Sting: Paul Newman and Robert Redford 7. GWTW: VL Gone with the Wind: Vivien Leigh 8. MOTOE: PU Murder on the Orient Express; Peter Ustinov (but it wasn’t it was Albert Finney! DOTN would be correct) 9. D: TH/HS/KB Dunkirk: Tom Hardy, Harry Styles, Kenneth Branagh 10. HN: GC High Noon: Gary Cooper 11. TS: JN The Shining: Jack Nicholson 12. G: BK Gandhi: Ben Kingsley 13. A: NK/HJ Australia: Nicole Kidman, Hugh Jackman 14. OGP: HF On Golden Pond: Henry Fonda 15. TDD: LM/CB/TS The Dirty Dozen: Lee Marvin, Charles Bronson, Telly Savalas 16. A: MC Alfie: Michael Caine 17. TDH: RDN The Deer Hunter: Robert De Niro 18. GWCTD: ST/SP Guess who’s coming to Dinner: Spencer Tracy, Sidney Poitier 19. TKS: CF The King’s Speech: Colin Firth 20. LOA: POT/OS Lawrence of Arabia: Peter O’Toole, Omar Shariff 21. C: ET/RB Cleopatra: Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton 22. MC: JV/DH Midnight Cowboy: Jon Voight, Dustin Hoffman 23. P: AP/JL Psycho: Anthony Perkins, Janet Leigh 24. TG: JW True Grit: John Wayne 25. TEHL: DS The Eagle has landed: Donald Sutherland. 26. SLIH: MM Some like it Hot: Marilyn Monroe 27. -

Voice Training and the Royal National Theatre Rena Cook

Spring 1999 165 Voice Training and the Royal National Theatre Rena Cook I stepped off the double-decker bus at Waterloo Station with my map in hand, walked several blocks and found the Old Vic quite easily. But the Royal National Theatre Studio, where the orientation was to take place, was nowhere in sight. "Next to the Old Vic," I had been told. With address and directions in my pocket, I surveyed the area as my internal compass spun out of control. After a brief moment of panic, I went to the box office and asked for help. "Out this door, two steps to your left and through the iron gate." I had traveled to London to participate in a course entitled "International Voice Intensive" with Patsy Rodenburg. As I walked up the steps of the studio on that chilly Sunday afternoon, with jet lag hanging heavily on my limbs, I had little idea that in my two weeks study I was about to experience a Zeitgeist of contemporary London theatre, training and practice. The focus was, of course, the voice work under the tutelage of master teacher Patsy Rodenburg, who currently heads the voice departments at the Royal National Theatre and Guildhall School of Music and Drama. In addition, the course participants were exposed to and interacted with some of the finest artists working in Western theatre today, including Trevor Nunn, Richard Eyre, and Judi Dench. Following each exhaustive day of study, workshop, and discussion, we attended theatre, viewing five of the six productions currently in repertory at the National. -

June 2016 President: Vice President: Simon Russell Beale CBE Nickolas Grace

No. 495 - June 2016 President: Vice President: Simon Russell Beale CBE Nickolas Grace Nothing like a Dame (make that two!) The VW’s Shakespeare party this year marked Shakespeare’s 452nd birthday as well as the 400th anniversary of his death. The party was a great success and while London, Stratford and many major cultural institutions went, in my view, a bit over-bard (sorry!), the VW’s party was graced by the presence of two Dames - Joan Plowright and Eileen Atkins, two star Shakespeare performers very much associated with the Old Vic. The party was held in the Old Vic rehearsal room where so many greats – from Ninette de Valois to Laurence Olivier – would have rehearsed. Our wonderful Vice-President, Nickolas Grace, introduced our star guests by talking about their associations with the Old Vic; he pointed out that we had two of the best St Joans ever in the room where they would have rehearsed: Eileen Atkins played St Joan for the Prospect Company at the Old Vic in 1977-8; Joan Plowright played the role for the National Theatre at the Old Vic in 1963. Nickolas also read out a letter from Ronald Pickup who had been invited to the party but was away in France. Ronald Pickup said that he often thought about how lucky he was to have six years at the National Theatre, then at Old Vic, at the beginning of his career (1966-72) and it had a huge impact on him. Dame Joan Plowright Dame Joan Plowright then regaled us with some of her memories of the Old Vic, starting with the story of how when she joined the Old Vic school in 1949 part of her ‘training’ was moving chairs in and out of the very room we were in. -

Thursday Friday

aw — a iic r inice ueorgc ^ in/eii,i v i uvjc.3 — depiemoer X4in, iyy«* The Prince George ★ ★ ★ ★ ...... ......E x c e lle n t M k e > ^ 3 < s ★ ★ ............. ..................Fair ★ ★ ★ ......... ★ ............... Norris. A master of the martial arts AFTERNOON the clutches of a cruel boarding school Harrison, Kay Kendall. The wife of a embarks on a revenge-motivated mistress to search for her soldier titled Englishman must introduce her search for the killers of his adopted 12:00 father. American-raised stepdaughter to son. (22) * *'■> “Spooner” (1989, Comedy- 1:3 0 London society. 8 :3 0 Drama) Robert Urich, Jane QD [12] (:35) “Betrayed by Love" 9 :0 0 (221 (:35) * * x “Eyes in the Night" Kaczmarek. An escaped counterfeiter (1994, Drama) Mare Winningham, © QD [12] **i4 “White Sands" (1942, Mystery) Edward Arnold, Ann finds life quite difficult when he tries to Steven Weber. The sibling of an FBI (1992, Suspense) Willem Dafoe, Harding. When an actor is found mur pass himself off as a high-school informant believes that her sister was Mickey Rourke. A New Mexico sherif dered. a sightless sleuth uncovers an teacher. A (CC) murdered by the married agent with f's unorthodox murder investigation espionage plot in the course of his 5:0 0 whom she had an affair. leads to the center of an international investigation. S3 (:05) * * * s “No Time for arms conspiracy. A (CC) 9 :0 0 Sergeants" (1958, Comedy) Andy 53 (:05) * * “Little Darlings" (1980, [24) (:05) * * s “The Taking of Griffith, Nick Adams. A Georgia farm FRIDAY Comedy) Tatum O’Neal, Kristy Pelham One, Two, Three" (1974, boy inducted into the service sets the McNichol. -

Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press 2021

Jan 21 #1 Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press Sherlockians (and Holmesians) did not gather in New York to celebrate the Great Detective’s 167th birthday this year, but the somewhat shorter long weekend offered plenty of events, thanks to Zoom and other modern technol- ogy. Detailed reports will be available soon at the web-site of The Baker Street Irregulars <www.bakerstreetirregulars.com>, but here are few brief paragraphs to tide you over: The BSI’s Distinguished Speaker on Thursday was Andrew Lycett, the author of two fine books about Conan Doyle; his topic was “Conan Doyle’s Questing World” (and close to 400 people were able to attend the virtual lecture); the event also included the announcement by Steve Rothman, editor of the Baker Street Journal, of the winner of the Morley-Montgomery Award for the best article the BSJ last year: Jessica Schilling (for her “Just His Type: An Analysis of the Découpé Warning in The Hound of the Baskervilles”). Irregulars and guests gathered on Friday for the BSI’s annual dinner, with Andrew Joffe offering the traditional first toast to Nina Singleton as The Woman, and the program continued with the usual toasts, rituals, and pap- ers; this year the toast to Mrs. Hudson was delivered by the lady herself, splendidly impersonated by Denny Dobry from his recreation of the sitting- room at 221B Baker Street. Mike Kean (the “Wiggins” of the BSI) presented the Birthday Honours (Irregular Shillings and Investitures) to Dan Andri- acco (St. Saviour’s Near King’s Cross), Deborah Clark (Mrs. Cecil Forres- ter), Carla Coupe (London Bridge), Ann Margaret Lewis (The Polyphonic Mo- tets of Lassus), Steve Mason (The Fortescue Scholarship), Ashley Polasek (Singlestick), Svend Ranild (A “Copenhagen” Label), Ray Riethmeier (Mor- rison, Morrison, and Dodd), Alan Rettig (The Red Lamp), and Tracy Revels (A Black Sequin-Covered Dinner-Dress). -

Foxcatcher Directed by Bennett Miller

Sony Pictures Classics Presents An Annapurna Pictures Production Foxcatcher Directed by Bennett Miller Cannes Film Festival 2014 Telluride Film Festival 2014 Toronto International Film Festival 2014 New York Film Festival 2014 Winner - Best Director, Cannes Film Festival 2014 134 mins | Rated R | Opens 11/14/14 (NY/LA) East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor 42West Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Scott Feinstein Max Buschman Carmelo Pirrone 220 West 42nd Street Blair Bender Maya Anand 12th floor 6100 Wilshire Blvd., 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10036 Ste. 170 New York, NY 10022 212-277-7555 Los Angeles, CA 90048 212-833-8833 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8844 fax 323-634-7030 fax FOXCATCHER The Cast John du Pont STEVE CARELL Mark Schultz CHANNING TATUM Dave Schultz MARK RUFFALO Jean du Pont VANESSA REDGRAVE Nancy Schultz SIENNA MILLER Jack ANTHONY MICHAEL HALL Henry Beck GUY BOYD Documentary Filmmaker DAVE “DOC” BENNETT The Filmmakers Director BENNETT MILLER Written by E. MAX FRYE DAN FUTTERMAN Producers MEGAN ELLISON BENNETT MILLER JON KILIK ANTHONY BREGMAN Executive Producers CHELSEA BARNARD RON SCHMIDT MARK BAKSHI MICHAEL COLEMAN TOM HELLER JOHN P. GUIRA Co-Producer SCOTT ROBERTSON Director of Photography GREIG FRASER Production Designer JESS GONCHOR Editor STUART LEVY CONOR O’NEILL JAY CASSIDY Costume Designer KASIA MAIMONE WALICKA Music ROB SIMONSEN Additional Music WEST DYLAN THORDSON Valley Forge Theme MYCHAEL DANNA Casting Director JEANNE McCARTHY Makeup Designer BILL CORSO Hair Department Head KATHRINE GORDON Wrestling Coordinator JOHN GUIRA Wrestling Choreographer JESSE JANTZEN 2 FOXCATCHER Synopsis Based on true events, FOXCATCHER tells the dark and fascinating story of the unlikely and ultimately tragic relationship between an eccentric multi-millionaire and two champion wrestlers.