Sunderland Point

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lancaster-Cultural-Heritage-Strategy

Page 12 LANCASTER CULTURAL HERITAGE STRATEGY REPORT FOR LANCASTER CITY COUNCIL Page 13 BLUE SAIL LANCASTER CULTURAL HERITAGE STRATEGY MARCH 2011 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................3 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................7 2 THE CONTEXT ................................................................................10 3 RECENT VISIONING OF LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE 24 4 HOW LANCASTER COMPARES AS A HERITAGE CITY...............28 5 LANCASTER DISTRICT’S BUILT FABRIC .....................................32 6 LANCASTER DISTRICT’S CULTURAL HERITAGE ATTRACTIONS39 7 THE MANAGEMENT OF LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE 48 8 THE MARKETING OF LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE.....51 9 CONCLUSIONS: SWOT ANALYSIS................................................59 10 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES FOR LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE .......................................................................................65 11 INVESTMENT OPTIONS..................................................................67 12 OUR APPROACH TO ASSESSING ECONOMIC IMPACT ..............82 13 TEN YEAR INVESTMENT FRAMEWORK .......................................88 14 ACTION PLAN ...............................................................................107 APPENDICES .......................................................................................108 2 Page 14 BLUE SAIL LANCASTER CULTURAL HERITAGE STRATEGY MARCH 2011 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Lancaster is widely recognised -

The First 40 Years

A HISTORY OF LANCASTER CIVIC SOCIETY THE FIRST 40 YEARS 1967 – 2007 By Malcolm B Taylor 2009 Serialization – part 7 Territorial Boundaries This may seem a superfluous title for an eponymous society, so a few words of explanation are thought necessary. The Society’s sometime reluctance to expand its interests beyond the city boundary has not prevented a more elastic approach when the situation demands it. Indeed it is not true that the Society has never been prepared to look beyond the City boundary. As early as 1971 the committee expressed a wish that the Society might be a pivotal player in the formation of amenity bodies in the surrounding districts. It was resolved to ask Sir Frank Pearson to address the Society on the issue, although there is no record that he did so. When the Society was formed, and, even before that for its predecessor, there would have been no reason to doubt that the then City boundary would also be the Society’s boundary. It was to be an urban society with urban values about an urban environment. However, such an obvious logic cannot entirely define the part of the city which over the years has dominated the Society’s attentions. This, in simple terms might be described as the city’s historic centre – comprising largely the present Conservation Areas. But the boundaries of this area must be more fluid than a simple local government boundary or the Civic Amenities Act. We may perhaps start to come to terms with definitions by mentioning some buildings of great importance to Lancaster both visually and strategically which have largely escaped the Society’s attentions. -

Delegated Planning List PDF 268 KB

LIST OF DELEGATED PLANNING DECISIONS LANCASTER CITY COUNCIL APPLICATION NO DETAILS DECISION 16/01081/VCN Agricultural Building Adj Disused Railway, Station Road, Application Permitted Hornby Erection of 9 dwellings and associated access (pursuant to the variation of condition no. 2 on application 14/01030/FUL to amend the approved plans to allow for additional amenity space and change of a 2 bed property to a 3 bed property) for Mr Ian Beardsworth (Upper Lune Valley Ward) 17/00192/DIS The Vicarage, Abbeystead Lane, Dolphinholme Discharge of Application Permitted condition 3 on approved application 17/00773/FUL for Mr Lee Donner (Ellel Ward 2015 Ward) 17/00199/DIS Land Adjacent To Bank Barn, Crag Road, Warton Discharge of Application Permitted conditions 3, 5, 6 and 9 on approved application 17/00897/VCN for Mr & Mrs D Hawkins (Warton Ward 2015 Ward) 17/00974/FUL Poole House, Main Street, Arkholme Erection of a detached Application Refused dwelling with associated hardstanding, landscaping and access for Mr & Mrs J Qualtrough (Kellet Ward 2015 Ward) 17/01325/VCN 7B Dalesview Crescent, Heysham, Morecambe Erection of 2 Application Refused semi-detached houses (pursuant to the variation of condition 1 and removal of 4 on planning permission 16/00757/VCN in relation to the location of fence and gate enclosing the garden of plot 2) for Mr Christopher Ian Hemingway (Heysham South Ward 2015 Ward) 17/01396/ADV Lancaster And Morecambe College, Morecambe Road, Application Permitted Lancaster Advertisement application for the display of a three panel -

Lancaster City Council Multi-Agency Flooding Plan

MAFP PTII Lancaster V3.2 (Public) June 2020 Lancaster City Council Multi-Agency Flooding Plan Emergency Call Centre 24-hour telephone contact number 01524 67099 Galgate 221117 Date June 2020 Current Version Version 3.2 (Public) Review Date March 2021 Plan Prepared by Mark Bartlett Personal telephone numbers, addresses, personal contact details and sensitive locations have been removed from this public version of the flooding plan. MAFP PTII Lancaster V3.2 (Public version) June 2020 CONTENTS Information 2 Intention 3 Intention of the plan 3 Ownership and Circulation 4 Version control and record of revisions 5 Exercises and Plan activations 6 Method 7 Environment Agency Flood Warning System 7 Summary of local flood warning service 8 Surface and Groundwater flooding 9 Rapid Response Catchments 9 Command structure and emergency control rooms 10 Role of agencies 11 Other Operational response issues 12 Key installations, high risk premises and operational sites 13 Evacuation procedures (See also Appendix ‘F’) 15 Vulnerable people 15 Administration 16 Finance, Debrief and Recovery procedures Communications 16 Equipment and systems 16 Press and Media 17 Organisation structure and communication links 17 Appendix ‘A’ Cat 1 Responder and other Contact numbers 18 Appendix ‘B’ Pumping station and trash screen locations 19 Appendix ‘C’ Sands bags and other Flood Defence measures 22 Appendix ‘D’ Additional Council Resources for flooding events 24 Appendix ‘E’ Flooding alert/warning procedures - Checklists 25 Appendix ‘F’ Flood Warning areas 32 Lancaster -

Byelaw 26 - Fixed Engines - Prohibitions and Authorisations (England)

NWSFC BYELAW 26 - FIXED ENGINES - PROHIBITIONS AND AUTHORISATIONS (ENGLAND). Byelaw confirmed 10.03.11 This byelaw applies to that part of the District within a line drawn on the seaward side of the baselines 6 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea adjacent to the United Kingdom is measured. For the purposes of this paragraph "the baselines" means the baselines as they existed at 25th January, 1983 in accordance with the Territorial Waters Order in Council 1964 (1965 III p.6452A) as amended by the Territorial Waters (Amendment) Order in Council 1979 (1979 II p.2866). a) The placing and use of fixed engines for the taking of sea fish is prohibited in those parts of the District numbered 1 to11 as defined in paragraph (c) below during the period 1st May to 30th November following except for: i. Anchored flue nets placed or used in the parts of the District numbered 2 and 3 during the period 1st July to 30th November following with the written permission of the Authority and subject to conditions 1) to 4) below and the conditions set out at paragraph b) below; (1) No net to exceed 75m in length when measured along the headline. (2) The elapsed time period between shooting the net and hauling the net shall not exceed 30 minutes. (3) All nets shall be actively worked by possing or splashing during the fishing operation. (4) Only one such net shall be carried or used at any time. ii. Moored whitebait filter nets placed or used seaward of a line drawn from Bazil Point (Latitude 54o 00.25’ North, Longitude 02o 51.50’ West) to Fishnet Point (Latitude 54o 00.03’ North, Longitude 02o 51.00’ West) in the part of the District numbered 5 during the periods 1st May to 31st May following and 1st September and 30th November following with the written permission of the Authority and subject to the conditions set out at paragraph b) below; iii. -

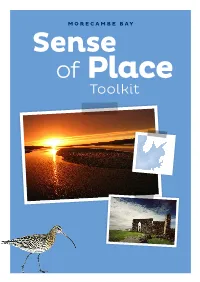

Morecambe Bay Sense of Place Toolkit

M o r e c a M b e b a y Sense of Place Toolkit Lune estuary sunset © Tony Riden St Patrick's Chapel © Alan Ferguson National Trust contents Page Introduction 3 What is Sense of Place? 3 Why is it Important? 3 © Susannah Bleakley This Sense of Place Toolkit 4 How can I Use Sense of Place? 5 What experiences do Visitors Want? 6 What Information do Visitors Need? 6 Susannah Bleakley Where and When can We Share Information? 7 Vibrant culture of arts and Festivals 30 Morecambe bay arts and architecture 30 Sense of Place Summary 9 Holiday Heritage 32 Morecambe bay Headlines 9 Holidays and Holy Days 33 Morecambe bay Map: From Walney to Wear 10 Local Food and Drink 34 Dramatic Natural Landscape Traditional recipes 36 and Views 12 Food experiences 37 captivating Views 13 Something Special 39 a changing Landscape 15 Space for exploration 40 Impressive and Dynamic Nature on your doorstep 41 Wildlife and Nature 16 Promote exploring on Foot 42 Nature rich Places 18 be cyclist Friendly 43 Spectacular species 20 Give the Driver a break 44 Nature for everyone 21 other Ways to explore 44 Fascinating Heritage on Water and Land 24 be a Part of the bay 45 Heritage around the bay 25 responsible Tourism Life on the Sands 26 in Morecambe bay 46 Life on the Land 28 acknowledgements 47 Introduction This Toolkit has been developed to help visitors discover the special character of Morecambe Bay. It aims to provide businesses around the Bay with a greater understanding of the different elements that make up the area’s special character, from its spectacular landscape and views, it’s geology, rich nature. -

Wildlife in North Lancashire 2015

Wildlife In North Lancashire 2015 34th Annual Newsletter of the North Lancashire Wildlife Group Price £2.50 North Lancashire Wildlife Group News from The Committee 2015 The Group is a local group of the Wildlife Trust for We must first of all apologise for the problems we have Lancashire, Manchester & N.Merseyside, primarily for had with our website this year which unfortunately was members living in the Lancaster City Council District and down for several months. It is now up and running immediately adjacent areas of Lancashire, South again, so we hope you will be able to access it easily Cumbria and North Yorkshire. and find information about our summer and winter programmes. Also, we do try to get our programmes of Meetings are open to all members of the Wildlife Trust. events onto the L.W.T. website ‘What`s On’ pages if If you are not already a member, come along to a few people also look there. meetings and, if you like what we do, join us. After many years, Brian Hugo has retired as the record- The Committee coordinates all the work of the Group er for Hoverflies and we would like to thank him for the and, in particular, arranges meetings, field outings, enthusiasm and expertise which he always brought to recording sessions, and the production of an annual the meetings. Michael Bloomfield has also retired as Newsletter. The Recorders receive and collate records Ladybird Recorder and is passing this role onto Rob to help conserve interesting sites, to monitor changing Zloch. Our thanks go to Mike for all his effort and time numbers and distribution of species and to contribute and we hope he will still join us on some of our field to national recording schemes. -

Lancaster City Council Multi-Agency Flooding Plan

Lancaster City Council PUBLIC Version Multi-Agency Flooding Plan Date 1st December 2015 Current Version Version 2.4 Review Date November 2016 Plan Prepared by Mark Bartlett/Adrian Morphet Telephone numbers and other personal contact details in this plan should be treated as confidential and not released to the public. A public version of this plan is on the City Council website and enquirers should be directed towards that document. Flooding plan PUBLIC Version 2.4 December 2015 CONTENTS Information 2 Intention 3 Intention of the plan 3 Ownership and Circulation 4 Version control and record of revisions 5 Exercises and Plan activations 6 Method 7 Environment Agency Flood Warning System 7 Summary of local flood warning service 8 Command structure and emergency control rooms 9 Role of agencies 10 Other Operational response issues 11 Surface and Groundwater flooding 13 Rapid Response Catchments 13 Key installations, high risk premises and operational sites 14 Evacuation procedures (See also Appendix ‘F’) 15 Vulnerable people 15 Administration 16 Finance, Debrief and Recovery procedures Communications 16 Lancaster City Council 16 Press and Media 17 Organisation structure and communication links 17 Appendix ‘A’ Cat 1 Responder and other Contact numbers 18 Appendix ‘B’ Pumping station and screen locations 20 Appendix ‘C’ Sands bags policy, suppliers and advice 23 Appendix ‘D’ Council Emergency Response Team 25 Appendix ‘E’ Flooding procedures - Checklists 26 Appendix ‘F’ Flood Warning areas 31 Lancaster District – detailed checklists SC2 Lancaster -

Heysham 2011 FINAL Front Cover

Cefas contract report C2848 Radiological Habits Survey: Heysham, 2011 2012 Environment Report RL 02/12 This page has been intentionally left blank Environment Report RL 02/12 Final report Radiological Habits Survey: Heysham, 2011 C.J. Garrod, F.J. Clyne, V.E. Ly and P. Rumney Peer reviewed by G.J. Hunt Approved for publication by W.C Camplin 2012 The work described in this report was carried out under contract to the Environment Agency, the Food Standards Agency and the Health and Safety Executive. Cefas contract C2848 FSA Project PAU 198 / Lot 7 / ERI006 This report should be cited as: Garrod, C.J., Clyne, F.J., Ly, V.E. and Rumney, P., 2012. Radiological Habits Survey: Heysham, 2011. RL 02/12. Cefas, Lowestoft A copy can be obtained by downloading from the Cefas website: www.cefas.defra.gov.uk © Crown copyright, 2012 2 Radiological Habits Survey: Heysham, 2011 CONTENTS SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................................. 7 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 11 1.1 Regulatory framework ........................................................................................................... 11 1.2 Radiological protection framework ........................................................................................ 12 2 THE SURVEY .............................................................................................................................. -

26.2 the Maritime Volunteer Year 26 Issue 2 June 2020.Cdr

The Maritime Volunteer The Journal of the Maritime Volunteer Service Year 26 Issue 2 June 2020 www.mvs.org.uk Registered Charity in England & Wales No. 1048454 and in Scotland SC 039269 Chairman’s Address We are about to take a small step towards normal operations. Council has approved a limited, cautious return to afloat activities, subject to strict conditions. This is primarily so that Units who have understandings with local river and port authorities can resume safety patrols if they have enough members who wish to do so. This is a welcome development. However enthusiasm must very much be tempered with reality. We still live in dangerous times. Covid-19 is still with us. It has killed one of our members. So we need to be extremely careful. IT IS NOT BUSINESS AS USUAL. Please remember that Council has ALLOWED some afloat operations to take place but it is definitely NOT REQUIRING Units, whether they have agreements with harbour masters or not, to resume safety patrols. Resumption of afloat activities may mainly be appropriate for younger, less-at-risk members. Council is NOT encouraging anybody who has doubts about getting involved in even restricted activities at this stage to take part. Members who are shielding must not get involved in any way until the arrangements concerning shielding are changed. Those over 70, or who for any reason may be considered vulnerable, should think carefully before putting themselves forward. The early indications are that only a limited number of Units will be running safety patrols in the next few weeks. -

The First 40 Years

A HISTORY OF LANCASTER CIVIC SOCIETY THE FIRST 40 YEARS 1967 – 2007 By Malcolm B Taylor 2009 Serialization – part 8 Design Awards As early as 1970, the committee proposed to set up Annual Awards. Presumably, these would be for buildings of civic merit, a direct ancestor of the present scheme, because the minutes record “commendations of praiseworthy new buildings”. However this intention resulted in awards for stone cleaning. Cash amounts were given for about nine streets. There were no further awards until 1981 when there was again a suggestion that the Society should organise awards for the best buildings. We had to wait until 1986 for action, when the Society, the Lancaster Guardian, Chamber of Commerce and the Town Hall joined in promoting a scheme for encouraging good civic design. It was described as “an experiment to promote good design in building”. At the time, Lancaster City was one of the “good design authorities”. Awards and commendations would be made for well designed buildings, usually, but not necessarily prominent in the public eye. Entries could be as small as domestic extensions. Awards would be made annually at an Awards ceremony in the town hall, the Awards certificates given by the Mayor to owners, designers and builders and published in the Lancaster Guardian. Any member of the public could nominate entries. The three bodies would be represented on the Awards panel, which would short list entries and make awards, to be known as Lancaster Design Awards. An external assessor, usually a respected local architect would lead in advising on choosing the successful entries. -

Five Year Housing Land Supply Position

2 Five year housing land supply position November 2020 1 Contents Page 1. Introduction 3 2. Background 3 3. Five-year housing land supply 6 4. Conclusion 10 Appendix 1 – Housing Land Supply Methodology 12 Appendix 2 – Five-year housing land supply trajectory 28 Appendix 3 – Schedule of Site Delivery 29 Appendix 4 – Small Site Commitment 59 June 2014 2 1. Introduction 1.1 This statement has been prepared, and should be read in conjunction, with the 2020 Housing Land Monitoring Report (HLMR). The statement describes the council’s five-year housing land supply position as of the 1st April 2020. The statement has been prepared in line with national planning policy and guidance and reports delivery against the now adopted housing requirement for the district, adopted by the Council on the 29th July 2020. 1.2 The statement has been prepared in line with the appended Lancaster District Housing Land Supply Methodology (appendix 1). This was prepared following discussions and engagement with representatives from the housing industry in April 2020. 1.3 The statement is supported by a detailed housing trajectory (appendix 2) setting out the sites where the council anticipates delivery and the expected rate of completions envisaged on each site. Further information on these sites is provided in a schedule of delivery (appendix 3). This provides a detailed breakdown of the supply and the evidence that has informed inclusion within the trajectory. 1.4 The delivery projections of sites is based on the evidence base collected and assessed by the Council which includes the conclusions of the council’s Strategic Housing and Employment Land Availability Assessment (SHELAA), the Local Plan evidence base, a review of planning applications and discussions with development management colleagues and importantly information provided from developers and agents on individual site delivery.