Glow-Voicesofdissent-2007.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A 'Common-Sense Revolution'? the Transformation of the Melbourne City

A ‘COMMON-SENSE REVOLUTION’? THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE MELBOURNE CITY COUNCIL, 1992−9 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April, 2015 Angela G. Munro Faculty of Business, Government and Law Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis University of Canberra ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis is the culmination of almost fifty years’ interest professionally and as a citizen in local government. Like many Australians, I suspect, I had barely noticed it until I lived in England where I realised what unique attributes it offered, despite the different constitutional arrangements of which it was part. The research question of how the disempowerment and de-democratisation of the Melbourne City Council from 1992−9 was possible was a question with which I had wrestled, in practice, as a citizen during those years. My academic interest was piqued by the Mayor of Stockholm to whom I spoke on November 18, 1993, the day on which the Melbourne City Council was sacked. ‘That couldn’t happen here’, he said. I have found the project a herculean labour, since I recognised the need to go back to 1842 to track the institutional genealogy of the City Council’s development in the pre- history period to 1992 rather than a forensic examination of the seven year study period. I have been exceptionally fortunate to have been supervised by John Halligan, Professor of Public Administration at University of Canberra. An international authority in the field, Professor Halligan has published extensively on Australian systems of government including the capital cities and the Melbourne City Council in particular. -

Letter from Melbourne Is a Monthly Public Affairs Bulletin, a Simple Précis, Distilling and Interpreting Mother Nature

SavingLETTER you time. A monthly newsletter distilling FROM public policy and government decisionsMELBOURNE which affect business opportunities in Australia and beyond. Saving you time. A monthly newsletter distilling public policy and government decisions which affect business opportunities in Australia and beyond. p11-14: Special Melbourne Opera insert Issue 161 Our New Year Edition 16 December 2010 to 13 January 2011 INSIDE Auditing the state’s affairs Auditor (VAGO) also busy Child care and mental health focus Human rights changes Labor leader no socialist. Myki musings. Decision imminent. Comrie leads Victorian floods Federal health challenge/changes And other big (regional) rail inquiry HealthSmart also in the news challenge Baillieu team appointments New water minister busy Windsor still in the news 16 DECEMBER 2010 to 13 JANUARY 2011 14 Collins Street EDITORIAL Melbourne, 3000 Victoria, Australia Our government warming up. P 03 9654 1300 Even some supporters of the Baillieu government have commented that it is getting off to a slow F 03 9654 1165 start. The fact is that all ministers need a chief of staff and specialist and other advisers in order to [email protected] properly interface with the civil service, as they apply their new policies and different administration www.letterfromcanberra.com.au emphases. These folk have to come from somewhere and the better they are, the longer it can take for them to leave their current employment wherever that might be and settle down into a government office in Melbourne. Editor Alistair Urquhart Some stakeholders in various industries are becoming frustrated, finding it difficult to get the Associate Editor Gabriel Phipps Subscription Manager Camilla Orr-Thomson interaction they need with a relevant minister. -

THE FAMOUS FACES WHO HELPED INSPIRE a GREAT KNIGHT for the Past 25 Years, GRANT Mcarthur Keating and Malcolm Hewitt Screaming “C’Mon”

06 NEWS THURSDAY, OCTOBER 8, 2015 HERALDSUN.COM.AU ALWAYS MAKING HEADLINES Melbourne legends, stars mark our milestone IT was aptly a headline- NUI TE KOHA, outed him and then-girlfriend a great move and it’s just gone grabbing event celebrating the JACKIE EPSTEIN Holly before they had gone on from strength to strength. I’m 25-year milestone of a news AND LUKE DENNEHY a second date. really honoured to be part of powerhouse. “We hadn’t had that chat,” this celebration ... It’s such a big About 350 prominent Mel- Television legend Newton Hughes said. part of Melbourne.” burnians gathered to honour said: “Melbourne is a great city Holly, a journalist, started Celebrity guests were in a the Herald Sun at a star-stud- but it’s made even better by working at the Herald Sun as a cheeky mood when photogra- ded party at The Emerson in institutions like the Herald Sun. “beautiful 22 year old,” he said. phers tried to get a shot of the South Yarra last night. “I can’t imagine Melbourne “For 10 years, not one editor assembled throng. Powerbrokers, including without it. hit on her. What is going on “(Jeff) Kennett will break Eddie McGuire, Michael Gud- “I’m a Melbourne boy, born there?” Hughes said. the camera,” John Elliott bel- inski, Jeanne Pratt, Robert and bred, and the Herald Sun is He said media mogul Ru- lowed. Doyle and Jeff Kennett, joined one of the important traditions pert Murdoch insisted Colling- Kennett retorted: “The legends, like Ian “Molly” Mel- of living here.” wood”s 1990 premiership win camera will break itself. -

1 Heat Treatment This Is a List of Greenhouse Gas Emitting

Heat treatment This is a list of greenhouse gas emitting companies and peak industry bodies and the firms they employ to lobby government. It is based on data from the federal and state lobbying registers.* Client Industry Lobby Company AGL Energy Oil and Gas Enhance Corporate Lobbyists registered with Enhance Lobbyist Background Limited Pty Ltd Corporate Pty Ltd* James (Jim) Peter Elder Former Labor Deputy Premier and Minister for State Development and Trade (Queensland) Kirsten Wishart - Michael Todd Former adviser to Queensland Premier Peter Beattie Mike Smith Policy adviser to the Queensland Minister for Natural Resources, Mines and Energy, LHMU industrial officer, state secretary to the NT Labor party. Nicholas James Park Former staffer to Federal Coalition MPs and Senators in the portfolios of: Energy and Resources, Land and Property Development, IT and Telecommunications, Gaming and Tourism. Samuel Sydney Doumany Former Queensland Liberal Attorney General and Minister for Justice Terence John Kempnich Former political adviser in the Queensland Labor and ACT Governments AGL Energy Oil and Gas Government Relations Lobbyists registered with Government Lobbyist Background Limited Australia advisory Pty Relations Australia advisory Pty Ltd* Ltd Damian Francis O’Connor Former assistant General Secretary within the NSW Australian Labor Party Elizabeth Waterland Ian Armstrong - Jacqueline Pace - * All lobbyists registered with individual firms do not necessarily work for all of that firm’s clients. Lobby lists are updated regularly. This -

Vic Libs Reeling Over Secret Baillieu Tape PUBLISHED: 24 JUN 2014 12:38:00 | UPDATED: 25 JUN 2014 05:58:53

Vic Libs reeling over secret Baillieu tape PUBLISHED: 24 JUN 2014 12:38:00 | UPDATED: 25 JUN 2014 05:58:53 LUCILLE KEEN AND MATHEW DUNCKLEY An embarrassing leaked recording of former Victorian premier Ted Baillieu criticising other Liberal MPs to journalists has inflamed tensions in the party. In the recording of a conversation with an Age journalist Mr Baillieu slammed the factional divides which led to the selection of Tim Smith to contest the blue-ribbon seat of Kew at the next election. Mr Baillieu supported front bencher Mary Wooldridge in her unsuccessful tilt for the seat. Mr Baillieu also criticises MPs Michael Gidley and Murray Thompson and the conservative faction that overturned Denis Napthine as opposition leader in 2002 to be replaced by Robert Doyle. “The technique with Michael Gidley was the technique with Tim Smith,” Mr Baillieu said. He also criticised balance-of-power MP Geoff Shaw. Mr Shaw quit the parliamentary Liberal Party, citing a lack of faith in the leadership, contributing to Mr Baillieu’s resignation hours later. “Shaw has been sponsored into his position by a bunch of people from the very first day led by Bernie Finn and some crazy mates in the parliamentary team and a very senior member of the organisation who is very close to [federal MP] Kevin Andrews,” he said. Mr Shaw said Mr Baillieu can hold his own opinions but the “sad thing is he didn’t allow” his backbenchers any opinions while he was premier. He said claims about his backers were false and he was in a safe Liberal seat, “he takes for granted”. -

Questions Without Notice Transport Accident Commission

QUESTIONS WITHOUT NOTICE Wednesday, 12 August 1992 ASSEMBLY 59 Wednesday, 12 August 1992 The SPEAKER - Order! The honourable member for Malvern is out of order, as he is well aware. I am quite prepared to take action against him if necessary. The SPEAKER (Hon. Ken Coghill) took the chair at Ms KIRNER - We have determined that there 10.34 a.m. and read the prayer. should be an ongoing dividend that ends up in people's incomes, that reduces business costs and provides community services. We believe this has a QUESTIONS WITHOUT NOTICE greater community benefit than a one-off reduction in premiums. This dividend is equivalent to 20 000 jobs, and when you are making decisions about TRANSPORT ACCIDENT Budgets in recession times, jobs and investment in COMMISSION people have to be the highest priority. The government, the TAC and the Victoria Police Mr KENNElT (Leader of the Opposition) - I refer the Premier to her statement in March this year have worked very hard to ensure that the TAC has when she was responding to the coalition's decision become more viable and has surplus assets because of the decline in the accident rate. That position is to transfer the interest liability for the Pyramid bail-out to the Transport Accident Commission not shared by the opposition which, as the Minister (T AC), which she then described as an inappropriate for Transport said the other day, would extend the licence to kill by raising the speed limit. way of using TAC funds, and ask: given her remarks, how does she now justify the highway robbery that her government intends to impose on Honourable members interjecting. -

In the Public Interest

In the Public Interest 150 years of the Victorian Auditor-General’s Office Peter Yule Copyright Victorian Auditor-General’s Office First published 2002 This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without prior written permission. ISBN 0 7311 5984 5 Front endpaper: Audit Office staff, 1907. Back endpaper: Audit Office staff, 2001. iii Foreword he year 2001 assumed much significance for the Victorian Auditor-General’s Office as Tit marked the 150th anniversary of the appointment in July 1851 of the first Victorian Auditor-General, Charles Hotson Ebden. In commemoration of this major occasion, we decided to commission a history of the 150 years of the Office and appointed Dr Peter Yule, to carry out this task. The product of the work of Peter Yule is a highly informative account of the Office over the 150 year period. Peter has skilfully analysed the personalities and key events that have characterised the functioning of the Office and indeed much of the Victorian public sector over the years. His book will be fascinating reading to anyone interested in the development of public accountability in this State and of the forces of change that have progressively impacted on the powers and responsibilities of Auditors-General. Peter Yule was ably assisted by Geoff Burrows (Associate Professor in Accounting, University of Melbourne) who, together with Graham Hamilton (former Deputy Auditor- General), provided quality external advice during the course of the project. -

From Charles La Trobe to Charles Gavan Duffy: Selectors, Squatters and Aborigines 3

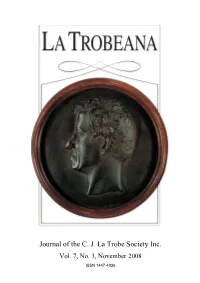

Journal of the C. J. La Trobe Society Inc. Vol. 7, No. 3, November 2008 ISSN 1447-4026 La Trobeana is kindly sponsored by Mr Peter Lovell LOVELL CHEN ARCHITECTS & HERITAGE CONSULTANTS LOVELL CHEN PTY LTD, 35 LITTLE BOURKE STREET, MELBOURNE 3000, AUSTRALIA Tel +61 (0)3 9667 0800 FAX +61 (0)3 9662 1037 ABN 20 005 803 494 La Trobeana Journal of the C J La Trobe Society Inc. Vol. 7, No. 3, November 2008 ISSN 1447-4026 For contributions contact: The Honorary Editor Dr Fay Woodhouse [email protected] Phone: 0427 042753 For subscription enquiries contact: The Honorary Secretary The La Trobe Society PO Box 65 Port Melbourne, Vic 3207 Phone: 9646 2112 FRONT COVER Thomas Woolner, 1825 – 1892, sculptor Charles Joseph La Trobe 1853, diam. 24.0cm. Bronze portrait medallion showing the left profile of Charles Joseph La Trobe. Signature and date incised in bronze I.I.: T. Woolner. Sc. 1853:/M La Trobe, Charles Joseph, 1801 – 1875. Accessioned 1894 La Trobe Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria. CONTENTS A Word from the President 1 Call for Assistance – Editorial Committee 1 Forthcoming Events 2 Christmas Cocktails 2 Government House Open Day 2 La Trobe’s Birthday 2009 2 A Word from the Treasurer 2 From Charles La Trobe to Charles Gavan Duffy: selectors, squatters and Aborigines 3 The Walmsley House at Royal Park: La Trobe’s “Other” Cottage 12 Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria 19 A Word from the President It is hard to believe that the year is nearly at an A highlight of the year was the inaugural La end. -

Neoliberalism Mark Lowes Proofs 2004

NEOLIBERAL POWER POLITICS AND THE CONTROVERSIAL SITING OF THE AUSTRALIAN GRAND PRIX MOTORSPORT EVENT IN AN URBAN PARK Mark LOWES Ottawa University Introduction This paper presents a case study of the Victorian State Government’s pursuit of a Formula One Grand Prix motorsport franchise and its controversial sitting in Melbourne’s Albert Park. In documenting the secret negotiations involved in securing the franchise and the subsequent process of transforming the park to accommodate the event, this c6ase study provides valuable insight into the state government’s autocratic approach to governance, public policy and, more specifi- cally, urban planning and development throughout the 1990s. During the 1990s Australian state governments adopted, in differing degrees, neoliberal urban development policies. As in other countries, these policies have quite dramatically increased social and economic inequalities and frequently pro- duced what Amin calls “fractured local economies, disempowered regions and fragmented local cultures” (1994:27). Nowhere is this more clear than the expe- rience of the State of Victoria under the Liberal government of Jeff Kennett, from 1992 to 1999. For several years following its electoral victory in 1992, the Kennett govern- ment proved to be the most active, controversial and ideological administration in twentieth-century Victoria. In its energetic implementation of an ideologically Loisir et société / Society and Leisure Volume 27, numéro 1, printemps 2004, p. 69-88 • © Presses de l’Université du Québec © 2004 – Presses de l’Université du Québec Édifice Le Delta I, 2875, boul. Laurier, bureau 450, Sainte-Foy, Québec G1V 2M2 • Tél. : (418) 657-4399 – www.puq.ca Tiré de : Loisir et société / Society and Leisure, vol. -

On the Couch with Robert Maclellan, 27 January 2015

On the Couch with Robert Maclellan, 27 January 2015 Grant Meyer MPIA CPP Photo: Robert Maclellan, January 2015 Planning News co-editor, Grant Meyer, recently caught up with former Kennett Government Planning Minister, Robert Maclellan, to reflect on his time in office. He speaks candidly on topics including: starting in the job, his relationship with the public service, local government, the planning profession, Docklands, Jeff Kennett, the former Kew asylum site and his legacy. For a man born on the 8th of March 1934, he is still exceptionally sharp and in good physical condition. He confides that he has recently had surgery to remove cataracts from his eyes and has subsequently experienced much improved sight. A review of parliamentary records reveals a 32 year career as a Liberal MP in the Victorian Parliament that included a stint as Leader of the Opposition (1982- 1985), a number of ministry positions, and for the purposes of this article, the Minister for Planning in the Kennett Government between 1992 and 1999. Planning News, 2015 1 Of note, in 2005 he was awarded the Member of the Order of Australia (AM) "for service to the Victorian Parliament, particularly in the areas of planning and transport, and to the community." Now living alone, he describes how his wife, Beverley, passed away in 2008 following a battle with bowel cancer. They had been married for 45 years. He has a good network of family and friends and gets out two evenings per week to play bridge locally. He’s not overly fond of the game but enjoys the social interaction with local men and women. -

The Banning of E.A.H. Laurie at Melbourne Teachers' College, 1944

THE BANNING OF E.A.H. LAURIE AT MELBOURNE TEACHERS' COLLEGE, 1944. 05 Rochelle White DEPARTMENT OF HUMANITIES Fourth Year Honours Thesis Faculty of Arts, Victoria University. December, 1997 FTS THESIS 323.4430994 WHI 30001004875359 White, Rochelle The banning of E.A.H. Laurie at Melbourne Teachers' College, 1944 TABLE OF CONTENTS Synopsis i Disclaimer ii Acknowledgments iii Chapter 1: Introduction 1-3 Chapter 2: Background 4-14 Chapters: Events 15-23 Chapter 4: Was the ban warranted? 24-29 Chapters: Conclusion 30-31 Bibliography Appendix: Constitution Alteration (War Aims and Reconstruction ) Bill - 1942 SYNOPSIS This thesis examines the banning of a communist speaker. Lieutenant E.A.H. Laurie, at Melbourne Teachers' College in July, 1944 and argues that the decision to ban Laurie was unwarranted and politically motivated. The banning, which was enforced by the Minister for Public Instruction, Thomas Tuke Hollway, appears to have been based on Hollway's firm anti-communist views and political opportunism. A. J. Law, Principal of the Teachers' College, was also responsible for banning Laurie. However, Law's decision to ban Laurie was probably directed by Hollway and supported by J. Seitz, Director of Education. Students at the neighbouring Melbourne University protested to defend the rights of Teachers' College students for freedom of speech. The University Labor Club and even the University Conservative Club argued that Hollway should have allowed Laurie to debate the "Yes" case for the forthcoming 1944 Powers Referendum. The "Fourteen Powers Referendum" sought the transfer of certain powers from the States to the Commonwealth for a period of five years after the war, to aid post-war reconstruction. -

Samuel Griffith Society Proceedings Vol 2

Proceedings of the Second Conference of The Samuel Griffith Society Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Two The Windsor Hotel, Melbourne; 30 July - 1 August 1993 Copyright 1993 by The Samuel Griffith Society. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Foreword (P4) John Stone Foreword Dinner Address (P5) The Hon. Jeff Kennett, MLA; Premier of Victoria The Crown and the States Introductory Remarks (P14) John Stone Introductory Chapter One (P15) Dr Frank Knopfelmacher The Crown in a Culturally Diverse Australia Chapter Two (P18) John Hirst The Republic and our British Heritage Chapter Three (P23) Jack Waterford Australia's Aborigines and Australian Civilization: Cultural Relativism in the 21st Century Chapter Four (P34) The Hon. Bill Hassell Mabo and Federalism: The Prospect of an Indigenous People's Treaty Chapter Five (P47) The Hon. Peter Connolly, CBE, QC Should Courts Determine Social Policy? Chapter Six (P58) S E K Hulme, AM, QC The High Court in Mabo Chapter Seven (P79) Professor Wolfgang Kasper Making Federalism Flourish Chapter Eight (P84) The Rt. Hon. Sir Harry Gibbs, GCMG, AC, KBE The Threat to Federalism Chapter Nine (P88) Dr Colin Howard Australia's Diminishing Sovereignty Chapter Ten (P94) The Hon. Peter Durack, QC What is to be Done? Chapter Eleven (P99) John Paul The 1944 Referendum Appendix I (P113) Contributors Appendix II (P116) The Society's Statement of Purposes Published 1993 by The Samuel Griffith Society P O Box 178, East Melbourne Victoria 3002 Printed by: McPherson's Printing Pty Ltd 5 Dunlop Rd, Mulgrave, Vic 3170 National Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data: Proceedings of The Samuel Griffith Society Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Two ISBN 0 646 15439 7 Foreword John Stone Copyright 1993 by The Samuel Griffith Society.