The Art of Piano Transcription As Critical Commentary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Homily 2Nd Sunday of Advent

Homily Bar 5: 1-9 Ps 126: 1-2, 2-3, 4-5, 6 2nd Sunday of Advent – C Phil 1: 4-6, 8-11 Rev. Peter G. Jankowski Lk 3: 1-6 December 8-9, 2018 The story I am about to share with you is entitled, The Cellist of Sarajevo and was written by Paul Sullivan for a periodical called Hope Magazine. This is the story… As a pianist, I was invited to perform with cellist Eugene Friesen at the International Cello Festival in Manchester, England. Every two years a group of the world’s greatest cellists and others devoted to that unassuming instrument – bow makers, collectors, historians – gather for a week of workshops, master classes, seminars, recitals and parties. Each evening the six hundred or so participants assemble for a concert. The opening-night performance at the Royal Northern College of Music consisted of works for unaccompanied cello. There on the stage in the magnificent concert hall was a solitary chair. No piano, no music stand, no conductor’s podium. This was to be cello music in its purest, most intense form. The atmosphere was supercharged with anticipation and concentration. The world-famous cellist Yo-Yo Ma was one of the performers that April night in 1994, and there was a moving story behind the musical composition he would play: On May 27, 1992, in Sarajevo, one of the few bakeries that still had a supply of flour was making and distributing bread to the starving, war-shattered people. At 4:00 p.m. a long line stretched into the street. -

Pastiche for Piano on Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji Op 6 Sheet Music

Pastiche For Piano On Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji Op 6 Sheet Music Download pastiche for piano on kaikhosru shapurji sorabji op 6 sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 4 pages partial preview of pastiche for piano on kaikhosru shapurji sorabji op 6 sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 2619 times and last read at 2021-09-28 10:12:03. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of pastiche for piano on kaikhosru shapurji sorabji op 6 you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Piano Method, Piano Solo Ensemble: Mixed Level: Advanced [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Opus Calidoscopium In Memory Of Sorabji Op 2 Opus Calidoscopium In Memory Of Sorabji Op 2 sheet music has been read 3180 times. Opus calidoscopium in memory of sorabji op 2 arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 4 preview and last read at 2021-09-26 19:02:59. [ Read More ] Pastiche 2017 Pastiche 2017 sheet music has been read 2663 times. Pastiche 2017 arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 02:51:33. [ Read More ] Virtuoso Etude No 4 In Memory Of Sorabji Nocturne Op 1 Virtuoso Etude No 4 In Memory Of Sorabji Nocturne Op 1 sheet music has been read 2729 times. Virtuoso etude no 4 in memory of sorabji nocturne op 1 arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 4 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 05:00:02. -

Toward a Lexicon for the Style Hongrois Jonathan D

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC School of Music Faculty Publications School of Music Spring 1991 Toward a Lexicon for the Style hongrois Jonathan D. Bellman Follow this and additional works at: https://digscholarship.unco.edu/musicfacpub Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Bellman, Jonathan D., "Toward a Lexicon for the Style hongrois" (1991). School of Music Faculty Publications. 2. https://digscholarship.unco.edu/musicfacpub/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Music at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Toward a Lexicon for the Style hongrois Author(s): Jonathan Bellman Source: The Journal of Musicology, Vol. 9, No. 2 (Spring, 1991), pp. 214-237 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/763553 . Accessed: 17/01/2015 20:21 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Musicology. -

A Scientific Characterization of Trumpet Mouthpiece Forces in the Context of Pedagogical Brass Literature

A SCIENTIFIC CHARACTERIZATION OF TRUMPET MOUTHPIECE FORCES IN THE CONTEXT OF PEDAGOGICAL BRASS LITERATURE James Ford III, B.M., M.M., M.M.E. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2007 APPROVED: Kris Chesky, Committee Chair Gene Cho, Minor Professor Leonard Candelaria, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Ford III, James, A Scientific Characterization of Trumpet Mouthpiece Forces in the Context of Pedagogical Brass Literature. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), December 2007, 61 pp., 7 tables, 2 graphs, references, 52 titles. Embouchure dysfunctions, including those from acute injury to the obicularis oris muscle, represent potential and serious occupational health problems for trumpeters. Forces generated between the mouthpiece and lips, generally a result of how a trumpeter plays, are believed to be the origin for such problems. In response to insights gained from new technologies that are currently being used to measure mouthpiece forces, belief systems and teaching methodologies may need to change in order to resolve possible conflicting terminology, pedagogical instructions, and performance advice. As a basis for such change, the purpose of this study was to investigate, develop and propose an operational definition of mouthpiece forces applicable to trumpet pedagogy. The methodology for this study included an analysis of writings by selected brass pedagogues regarding mouthpiece force. Finding were extracted, compared, and contrasted with scientifically derived mouthpiece force concepts developed from scientific studies including one done at the UNT Texas Center for Music & Medicine. -

Interpreting Tempo and Rubato in Chopin's Music

Interpreting tempo and rubato in Chopin’s music: A matter of tradition or individual style? Li-San Ting A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of the Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences June 2013 ABSTRACT The main goal of this thesis is to gain a greater understanding of Chopin performance and interpretation, particularly in relation to tempo and rubato. This thesis is a comparative study between pianists who are associated with the Chopin tradition, primarily the Polish pianists of the early twentieth century, along with French pianists who are connected to Chopin via pedagogical lineage, and several modern pianists playing on period instruments. Through a detailed analysis of tempo and rubato in selected recordings, this thesis will explore the notions of tradition and individuality in Chopin playing, based on principles of pianism and pedagogy that emerge in Chopin’s writings, his composition, and his students’ accounts. Many pianists and teachers assume that a tradition in playing Chopin exists but the basis for this notion is often not made clear. Certain pianists are considered part of the Chopin tradition because of their indirect pedagogical connection to Chopin. I will investigate claims about tradition in Chopin playing in relation to tempo and rubato and highlight similarities and differences in the playing of pianists of the same or different nationality, pedagogical line or era. I will reveal how the literature on Chopin’s principles regarding tempo and rubato relates to any common or unique traits found in selected recordings. -

8.111327 Bk Cortot EU 13/7/08 22:47 Page 4

8.111327 bk Cortot EU 13/7/08 22:47 Page 4 GREAT PIANISTS • ALFRED CORTOT Fryderyk CHOPIN (1810 - 1849) Waldszenen, Op. 82 CHOPIN: Piano Sonata No. 2, Op. 35 Piano Sonata No. 2 in B flat minor, Op. 35 * No. 7. Vogel als Prophet 2:36 “Funeral March” 17:36 Recorded 19th April 1948 1 I. Grave - Doppio movimento 5:25 in EMI Abbey Road Studio No. 3 SCHUMANN: Kinderszenen Op. 15 2 II. Scherzo 4:50 First issued on HMV ALP 1197 3 III. Marche funèbre: Lento 5:42 Matrix no.: 0EA 12922 4 IV. Finale: Presto 1:39 Carnaval, Op. 9 Recorded 7th-8th May 1953 Carnaval, Op. 9 25:29 in EMI Abbey Road Studio No. 3 ( No. 1. Préambule 2:36 RED CORT First issued on RCA Victor LHMV 18 ) No. 2. Pierrot 1:08 LF OT ¡ No. 3. Arlequin 0:43 A Robert SCHUMANN (1810 - 1856) ™ No. 4. Valse noble 1:19 Kinderszenen, Op. 15 17:15 £ 5 No. 5. Eusebius 1:30 No. 1. Von fremden Ländern und Menschen 1:39 ¢ No. 6. Florestan 0:53 (About foreign lands and peoples) – 6 No. 7. Coquette 1:01 No. 2. Curiose Geschichte 0:58 § No. 8. Réplique 0:26 (A curious story) ¶ 7 Sphinx 1-3 0:23 No. 3. Hasche-Mann 0:34 • No. 9. Papillons 0:43 (Catch me if you can) ª 8 No. 10. A.S.C.H. - S.C.H.A. No. 4. Bittendes Kind 0:51 (Lettres dansantes) 0:38 (Pleading child) º 9 No. 11. Chiarina 0:49 No. -

Notes on the Music

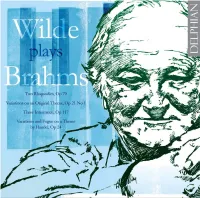

Notes on the music What are Brahms? This amusing gaffe may be But whatever your view you will surely see them, familiar but it ironically suggests a plurality and, in the words of the poet William Ritter, as ‘like in the case of the piano music, a panorama of the lustre of golden parks in autumn and the infinite richness and range. At the age of twenty austere black and white of winter walks’: a fitting Brahms introduced himself to Robert and Clara conclusion to an autobiographical journey of Schumann playing his piano sonatas and leaving exultant and reflective glory. them awed and enchanted by the sheer size and grandeur of his talent. For them he was But enough of generality. David Wilde’s richly already ‘fully armed’ and for Clara, in particular, a comprehensive programme opens with a young eagle had spread the wings of his genius. dramatic curtain-raiser – the two Rhapsodies The sonatas are, indeed, heroic utterances, Op 79, a notable return to Brahms’ Sturm und remembering Beethoven yet leaping into new Drang Romanticism. Here the terse opening realms of expression and an altogether novel of the B minor Rhapsody and its pleading, Romantic rhetoric. Such youthful outpouring was, Schumannesque second subject give us Brahms’ however, short-lived; Brahms turned gratefully old rhetorical sense of contrast, with an additional to variation form, finding the genre congenial to surprise in the form of a final dark-hued reworking his ever-growing mastery and imagination. of the central molto dolce expressivo’s chiming, bell-like counterpoints. The G minor Rhapsody is Throughout his life there would be temporary dominated by a powerful, arching melody and a returns to his early boldness, a memory no sombre triplet figure deployed with great ingenuity. -

Rachmaninoff's Early Piano Works and the Traces of Chopin's Influence

Rachmaninoff’s Early Piano works and the Traces of Chopin’s Influence: The Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 & The Moments Musicaux, Op.16 A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Division of Keyboard Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music by Sanghie Lee P.D., Indiana University, 2011 B.M., M.M., Yonsei University, Korea, 2007 Committee Chair: Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract This document examines two of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s early piano works, Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 (1892) and Moments Musicaux, Opus 16 (1896), as they relate to the piano works of Frédéric Chopin. The five short pieces that comprise Morceaux de Fantaisie and the six Moments Musicaux are reminiscent of many of Chopin’s piano works; even as the sets broadly build on his character genres such as the nocturne, barcarolle, etude, prelude, waltz, and berceuse, they also frequently are modeled on or reference specific Chopin pieces. This document identifies how Rachmaninoff’s sets specifically and generally show the influence of Chopin’s style and works, while exploring how Rachmaninoff used Chopin’s models to create and present his unique compositional identity. Through this investigation, performers can better understand Chopin’s influence on Rachmaninoff’s piano works, and therefore improve their interpretations of his music. ii Copyright © 2018 by Sanghie Lee All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements I cannot express my heartfelt gratitude enough to my dear teacher James Tocco, who gave me devoted guidance and inspirational teaching for years. -

An Attempt to Define Ignacy Jan Paderewski's Performing Style

An Attempt to Define Ignacy Jan Paderewski’s Performing Style by Prof. Lidia Kozubek Prof. Lidia Kozubek, concert pianist and one of Poland’s most prominent piano educators, is well known to music lovers in nearly all European countries as well as in Africa, both Americas, Asia, Australia and New Zealand. Besides concertizing and recording music, Prof. Kozubek is a faculty member of the Warsaw Academy of Music. She has also taught a number of piano students in other countries (such as Japan, Norway, Taiwan and Philippines just to mention a few) as a visiting professor or lecturer. For her artistic and educational achievement Prof. Kozubek received highly regarded national distinctions from Polish government, including the Chevalier Cross “Polonia Restituta.” An inquiry as to who was Paderewski seems to be a good starting point for a discussion of the pianist’s performing style. Paderewski was without doubt a personality of his times. Even among the greatest contemporary musicians, Paderewski remains a phenomenon. He had extraordinary combination of virtues, a multitude of talents and, above all, personal charm, unusual honesty and decency. All of these qualities allowed him to be highly successful in a variety of fields. Paderewski was simply an exceptional human figure. The legend surrounding his pianism is justified not only by his musical genius, but also by the richness of his character, which certainly had an impact on his performing style. As a composer, Paderewski was not always appreciated, but he definitely had a solid theoretical background and developed a strong individual style in which the “Polish tone” is easily found. -

A/L CHOPIN's MAZURKA

17, ~A/l CHOPIN'S MAZURKA: A LECTURE RECITAL, TOGETHER WITH THREE RECITALS OF SELECTED WORKS OF J. S. BACH--F. BUSONI, D. SCARLATTI, W. A. MOZART, L. V. BEETHOVEN, F. SCHUBERT, F. CHOPIN, M. RAVEL AND K. SZYMANOWSKI DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial. Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By Jan Bogdan Drath Denton, Texas August, 1969 (Z Jan Bogdan Drath 1970 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION . I PERFORMANCE PROGRAMS First Recital . , , . ., * * 4 Second Recital. 8 Solo and Chamber Music Recital. 11 Lecture-Recital: "Chopin's Mazurka" . 14 List of Illustrations Text of the Lecture Bibliography TAPED RECORDINGS OF PERFORMANCES . Enclosed iii INTRODUCTION This dissertation consists of four programs: one lec- ture-recital, two recitals for piano solo, and one (the Schubert program) in combination with other instruments. The repertoire of the complete series of concerts was chosen with the intention of demonstrating the ability of the per- former to project music of various types and composed in different periods. The first program featured two complete sets of Concert Etudes, showing how a nineteenth-century composer (Chopin) and a twentieth-century composer (Szymanowski) solved the problem of assimilating typical pianistic patterns of their respective eras in short musical forms, These selections are preceded on the program by a group of compositions, consis- ting of a. a Chaconne for violin solo by J. S. Bach, an eighteenth-century composer, as. transcribed for piano by a twentieth-century composer, who recreated this piece, using all the possibilities of modern piano technique, b. -

Whose Chopin? Politics and Patriotism in a Song to Remember (1945)

Whose Chopin? Politics and Patriotism in A Song to Remember (1945) John C. Tibbetts Columbia Pictures launched with characteristic puffery its early 1945 release, A Song to Remember, a dramatized biography of nineteenth-century composer Frederic Chopin. "A Song to Remember is destined to rank with the greatest attractions since motion pictures began," boasted a publicity statement, "—seven years of never-ending effort to bring you a glorious new landmark in motion picture achievement."1 Variety subsequently enthused, "This dramatization of the life and times of Frederic Chopin, the Polish musician-patriot, is the most exciting presentation of an artist yet achieved on the screen."2 These accolades proved to be misleading, however. Viewers expecting a "life" of Chopin encountered a very different kind of film. Instead of an historical chronicle of Chopin's life, times, and music, A Song to Remember, to the dismay of several critics, reconstituted the story as a wartime resistance drama targeted more to World War II popular audiences at home and abroad than to enthusiasts of nineteenth-century music history.3 As such, the film belongs to a group of Hollywood wartime propaganda pictures mandated in 1942-1945 by the Office of War Information (OWI) and its Bureau of Motion Pictures (BMP)—and subject, like all films of the time, to the censorial constraints of the Production Code Administration (PCA)—to stress ideology and affirmation in the cause of democracy and to depict the global conflict as a "people's war." No longer was it satisfactory for Hollywood to interpret the war on the rudimentary level of a 0026-3079/2005/4601-115$2.50/0 American Studies, 46:1 (Spring 2005): 115-142 115 116 JohnC.Tibbetts Figure 1: Merle Oberon's "George Sand" made love to Cornel Wilde's "Frederic Chopin" in the 1945 Columbia release, A Song to Remember(couvtQsy Photofest). -

Balys DVARIONAS (1904-1972) Complete Works for Violin and Piano Sonata-Ballade • Pezzo Elegiaco • Three Pieces

Balys DVARIONAS (1904-1972) Complete Works for Violin and Piano Sonata-Ballade • Pezzo elegiaco • Three Pieces Justina Auškelytė, Violin • Cesare Pezzi, Piano Balys Dvarionas (1904-1972) Complete Works for Violin and Piano Balys Dvarionas was one of the most prominent figures in Igor Stravinsky and Sergey Prokofiev, among others. The pianist, and his son, the violinist. There can be little doubt Sonata was meant to be a one-movement composition the field of Lithuanian (and indeed Baltic) musical culture. last time Dvarionas appeared on stage was on May 12, as to why Dvarionas’ instrumental chamber works are with the main theme reprised in the recapitulation. During A polymath, he excelled as a pianist, conductor, 1972 at the Lithuanian National Philharmonic in Vilnius, said to possess an especially personal quality. In the creative process each musical idea inspired the next, composer and pedagogue. Dvarionas was born in the where together with the Lithuanian Chamber Orchestra composing music for his children, the composer and so the work can be viewed as one constantly evolving Latvian harbour city of Liepaja. His father was a Roman he played Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in D major, inadvertently developed a particularly original chamber beautiful episodic sequence. A colleague of the composer Catholic church organist, and as a result the young K.107 and conducted Schubert’s Mass No. 2 in G major music idiom, where the interplay between parts relies on once described the work in the following terms: “…when Dvarionas received his first music lessons at home. He D.167. an uninhibited bond between performers.