Riverkeeper Is a Non-Profit Organization That Works to Protect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Journal

THE CITY RECORD. OFFICIAL JOURNAL. Vol.. YYVII. NEW YORK, FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 8, 1899. NUMBER 8,009. CITY OF NEW YORK—FINANCE DEPARTMENT, COMPTROLLER'S OFFICE, SL August 19, 1899. Hon. WILLIAM DALTON, Commissioner of Water Supply DEAR SIR—In order that I may have before me all the information possible in regard to the proposed contract with the Ramapo Water Company, I respectfully request you to transmit all the data upon which "as based your report presented to the Board of Public Improvements at its last meeting on Wednesday the 16th instant. I also request to be advised of the plans made by your department for utilizing the water delivered by the Ramapo Water Company to. The City of New York—i.e., the size and location of the storage reservoirs, aqueducts, pipe lines, principal distributing mains, and other accessories necessary for the distribution of such water, together with your estimates of cost thereof. III view of the short time allotted to me by the Board of Public Improvements for an examina- tion of this immensely important subject, I respectfully request that you furnish this information at your earliest possible convenience. Very truly yours, BIRD S. COLER, Comptroller. DEPARTMENT OF WATER SUPPLY, NEW YORK, August 2I, 1899. BOARD OF PUBLIC IMPROVEMENTS. Hon. BIRD S. COLER, Comptroller. DEAR SIR—Your favor of the 19th instant, addressed to the Commissioner, requesting all the '.xta upon which the Commissioner's report regarding the Ramapo Water Company was based, is The Board of Public Improvements of The City of New York met at the office of the Board, received. -

Report Measures the State of Parks in Brooklyn

P a g e | 1 Table of Contents Introduction Page 2 Methodology Page 2 Park Breakdown Page 5 Multiple/No Community District Jurisdictions Page 5 Brooklyn Community District 1 Page 6 Brooklyn Community District 2 Page 12 Brooklyn Community District 3 Page 18 Brooklyn Community District 4 Page 23 Brooklyn Community District 5 Page 26 Brooklyn Community District 6 Page 30 Brooklyn Community District 7 Page 34 Brooklyn Community District 8 Page 36 Brooklyn Community District 9 Page 38 Brooklyn Community District 10 Page 39 Brooklyn Community District 11 Page 42 Brooklyn Community District 12 Page 43 Brooklyn Community District 13 Page 45 Brooklyn Community District 14 Page 49 Brooklyn Community District 15 Page 50 Brooklyn Community District 16 Page 53 Brooklyn Community District 17 Page 57 Brooklyn Community District 18 Page 59 Assessment Outcomes Page 62 Summary Recommendations Page 63 Appendix 1: Survey Questions Page 64 P a g e | 2 Introduction There are 877 parks in Brooklyn, of varying sizes and amenities. This report measures the state of parks in Brooklyn. There are many different kinds of parks — active, passive, and pocket — and this report focuses on active parks that have a mix of amenities and uses. It is important for Brooklynites to have a pleasant park in their neighborhood to enjoy open space, meet their neighbors, play, and relax. While park equity is integral to creating One Brooklyn — a place where all residents can enjoy outdoor recreation and relaxation — fulfilling the vision of community parks first depends on measuring our current state of parks. This report will be used as a tool to guide my parks capital allocations and recommendations to the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation (NYC Parks), as well as to identify recommendations to improve advocacy for parks at the community and grassroots level in order to improve neighborhoods across the borough. -

2006 - 2007 Report Front Cover: Children Enjoying a Summer Day at Sachkerah Woods Playground in Van Cortlandt Park, Bronx

City of New York Parks & Recreation 2006 - 2007 Report Front cover: Children enjoying a summer day at Sachkerah Woods Playground in Van Cortlandt Park, Bronx. Back cover: A sunflower grows along the High Line in Manhattan. City of New York Parks & Recreation 1 Daffodils Named by Mayor Bloomberg as the offi cial fl ower of New York City s the steward of 14 percent of New York City’s land, the Department of Parks & Recreation builds and maintains clean, safe and accessible parks, and programs them with recreational, cultural and educational Aactivities for people of all ages. Through its work, Parks & Recreation enriches the lives of New Yorkers with per- sonal, health and economic benefi ts. We promote physical and emotional well- being, providing venues for fi tness, peaceful respite and making new friends. Our recreation programs and facilities help combat the growing rates of obesity, dia- betes and high blood pressure. The trees under our care reduce air pollutants, creating more breathable air for all New Yorkers. Parks also help communities by boosting property values, increasing tourism and generating revenue. This Biennial Report covers the major initiatives we pursued in 2006 and 2007 and, thanks to Mayor Bloomberg’s visionary PlaNYC, it provides a glimpse of an even greener future. 2 Dear Friends, Great cities deserve great parks and as New York City continues its role as one of the capitals of the world, we are pleased to report that its parks are growing and thriving. We are in the largest period of park expansion since the 1930s. Across the city, we are building at an unprecedented scale by transforming spaces that were former landfi lls, vacant buildings and abandoned lots into vibrant destinations for active recreation. -

Sub-Group Ii—Thematic Arrangement

U.S. SHEET MUSIC COLLECTION SUB-GROUP II—THEMATIC ARRANGEMENT Consists of vocal and instrumental sheet music organized by designated special subjects. The materials have been organized variously within each series: in certain series, the music is arranged according to the related individual, corporate group, or topic (e.g., Personal Names, Corporate, and Places). The series of local imprints has been arranged alphabetically by composer surname. A full list of designated subjects follows: ______________________________________________________________________________ Patriotic Leading national songs . BOX 458 Other patriotic music, 1826-1899 . BOX 459 Other patriotic music, 1900– . BOX 460 National Government Presidents . BOX 461 Other national figures . BOX 462 Revolutionary War; War of 1812 . BOX 463 Mexican War . BOX 464 Civil War . BOXES 465-468 Spanish-American War . BOX 469 World War I . BOXES 470-473 World War II . BOXES 474-475 Personal Names . BOXES 476-482 Corporate Colleges and universities; College fraternities and sororities . BOX 483 Commercial entities . BOX 484 1 Firemen; Fraternal orders; Women’s groups; Militia groups . BOX 485 Musical groups; Other clubs . BOX 486 Places . BOXES 487-493 Events . BOX 494 Local Imprints Buffalo and Western New York imprints . BOXES 495-497 Other New York state and Pennsylvania imprints . BOX 498 Rochester imprints . BOXES 499-511 ______________________________________________________________________________ 2 U.S. Sheet Music Collection Ruth T. Watanabe Special Collections, Sibley Music Library Sub-Group II PATRIOTIC SERIES Leading National Songs Box 458 Ascher, Gustave, arr. America: My Country Tis of Thee. For voice and piano. In National Songs. New York: S. T. Gordon, 1861. Carey, Henry, arr. America: The United States National Anthem. -

Detailed Report. New Construction Work Paid for out of Corporate Stock

PART 11. DETAILED REPORT. NEW CONSTRUCTION WORK PAID FOR OUT OF CORPORATE STOCK. Shore Road. The contract for the completion of the sea wall along the Shore Road, between Latting Place and Bay Ridge Avenue, and between 92d Street and Fort Hamilton Avenue, which was begun in 1914, was practically completed during 1915. The work consisted of constructing 6,624 linear feet of granite ashlar and concrete sea wall, furnishing and placing 46,000 tons of rip-rap and 350,000 cubic yards of earth fill. The contract for the furnishing and deposit- ing of 250,000 cubic yards of earth fill along the Shore Road, between 94th Street and Fort Hamilton Avenue, was begun during June, 1915. The work of filling in has been more than 50 per cent. completed this year. Dreamland Park. The contract for the construction of seven timber groynes along the beach front of Dreamland Park was completed during May, 1915. The cost of the work was $11,688.60. The purpose has been to stop the washing away of the beach. Records show that since 1874 more than 30 acres of public beach at Coney Island has been lost in this way. At one point, near the foot of the Ocean Boulevard, the Shore line has receded 1,100 feet. Since these groynes have been completed they have protected the beach from erosion and have also reclaimed considerable beach lands. In the spring they will be built up further and more land reclaimed. The contract for the removal of the old timber steamboat pier in front of Dreamland Park was begun during May, 1915. -

NYS OSP Appendix F

e-Appendix F – ASSESSMENT OF PUBLIC COMMENT e-Appendix F ASSESSMENT OF PUBLIC COMMENT ON THE 2014 DRAFT PLAN In 2013, DEC and OPRHP began the process of updating the 2009 Plan, asking the Regional Advisory Committees for recommendations. These suggestions and other public comments received since the publication of the 2009 Plan were evaluated, along with changes in the law, regulations and the Agencies' programs, to prepare a revised Plan. The Draft Plan was made available for public comment beginning on September 17, 2014 and ending on December 17, 2014. A statewide set of public hearings and workshops on the documents served to answer questions and receive comments. Public comments were received via the public hearings, mail, E-mail and through DEC's website established for the Open Space Conservation Plan (www.dec.ny.gov/lands/98720.html). A total of 462 people and organizations commented on the Draft Plan. A list of the commenters is included in e-Appendix G. The State open space conservation plan outlines a series of policy and program recommendations to enhance efforts that are on-going in New York State to advance Open space conservation at the state and local level with the many partners that are involved in this effort. Open space conservation provides multiple benefits: it helps sustain economically important sectors including agriculture, forestry, outdoor recreation and tourism; provides habitat for wildlife; protects water and air quality, ecosystems and endangered species; provides the basis for outdoor recreational activities, improves surrounding property values and community attractiveness, and in this era of rapid climate change, helps improve resilience to communities and private land owners. -

The Urban Audubon

The newsletter of New York City Audubon Win t erWin 2014-2015ter 2014 / /Volume Volume XXXV XXXV N No.o. 4 4 THE URBAN AUDUBON Audubon’sAudubon’s ClimateClimate ChangeChange ReportReport AA CallCall toto CitizenCitizen ScientistsScientists Winter 2014-2015 1 61246_NYC_Audubon_UA_Winter_Corr.indd 1 11/12/14 6:13 AM NYC AUDUBON MISSION & VISION Mission: NYC Audubon is a grassroots Bird’s-Eye View Kathryn Heintz community that works for the protection of wild birds and habitat in the five boroughs, improving the quality of life for all New Yorkers. idway through an otherwise quiet summer, the board of directors of New York Vision: NYC Audubon envisions a City Audubon invited me to become its next executive director. I am honored. day when birds and people in the MAs this dedicated and accomplished organization embarks upon its 35th year, five boroughs enjoy a healthy, livable I am thrilled to join its wonderful staff, to meet its devoted members, and to help craft its habitat. promising future. THE URBAN AUDUBON In just a few weeks, I have seen places I thought I knew: Jamaica Bay, Orchard Beach, Editors Lauren Klingsberg & Greenpoint, the coastline in Staten Island, and even a garage roof in the Battery. But now Marcia T. Fowle that I am looking at them with a bird’s-eye view, I am filled with wonder. Dr. Susan Elbin Managing Editor Tod Winston Newsletter Committee Lucienne Bloch, took me to the Battery to keep an eye out for night-migrating birds during the annual Ned Boyajian, Suzanne Charlé, Diane Tribute in Light memorial. -

Brooklyn-Queens Greenway Guide

TABLE OF CONTENTS The Brooklyn-Queens Greenway Guide INTRODUCTION . .2 1 CONEY ISLAND . .3 2 OCEAN PARKWAY . .11 3 PROSPECT PARK . .16 4 EASTERN PARKWAY . .22 5 HIGHLAND PARK/RIDGEWOOD RESERVOIR . .29 6 FOREST PARK . .36 7 FLUSHING MEADOWS CORONA PARK . .42 8 KISSENA-CUNNINGHAM CORRIDOR . .54 9 ALLEY POND PARK TO FORT TOTTEN . .61 CONCLUSION . .70 GREENWAY SIGNAGE . .71 BIKE SHOPS . .73 2 The Brooklyn-Queens Greenway System ntroduction New York City Department of Parks & Recreation (Parks) works closely with The Brooklyn-Queens the Departments of Transportation Greenway (BQG) is a 40- and City Planning on the planning mile, continuous pedestrian and implementation of the City’s and cyclist route from Greenway Network. Parks has juris- Coney Island in Brooklyn to diction and maintains over 100 miles Fort Totten, on the Long of greenways for commuting and Island Sound, in Queens. recreational use, and continues to I plan, design, and construct additional The Brooklyn-Queens Greenway pro- greenway segments in each borough, vides an active and engaging way of utilizing City capital funds and a exploring these two lively and diverse number of federal transportation boroughs. The BQG presents the grants. cyclist or pedestrian with a wide range of amenities, cultural offerings, In 1987, the Neighborhood Open and urban experiences—linking 13 Space Coalition spearheaded the parks, two botanical gardens, the New concept of the Brooklyn-Queens York Aquarium, the Brooklyn Greenway, building on the work of Museum, the New York Hall of Frederick Law Olmsted, Calvert Vaux, Science, two environmental education and Robert Moses in their creations of centers, four lakes, and numerous the great parkways and parks of ethnic and historic neighborhoods. -

FDNY Medal Day 2019

FDNY Medal Day 2019 Honoring Members of the Fire Department — June 5, 2019— MEDAL DAY 2019 Publication of this 2019 edition of the FDNY Medal Day Book Daniel A. Nigro was made possible by several grants. The FDNY gratefully Fire Commissioner acknowledges the generosity of the following contributors: John Sudnik Chief of Department The FDNY Honorary Fire Officers Association Laura R. Kavanagh Jack Lerch, President First Deputy Commissioner Francis X. Gribbon Deputy Commissioner Dorothy Marks Office of Public Information Honorary Fire Commissioner The FDNY Foundation Stephen L. Ruzow, Chairman Jean O’Shea, Executive Director MEDAL DAY STAFF PUBLICATIONS DIRECTOR Joseph D. Malvasio EDITOR Janet Kimmerly GRAPHICS/PRODUCTION Thomas Ittycheria WRITERS Lieutenant John Amsterdam Lieutenant John C. Berna Deputy Assistant Chief Christopher Boyle Captain Patrick Burns Lieutenant Anthony Caterino EMT Nathan Chang Lieutenant Michael Ciampo Captain Michael Doda Assistant Chief Fire Marshal Michael B. Durkin Proudly Serving Since 1865 Firefighter Jacob Dutton Captain Christopher Flatley Lieutenant James Gerber Lieutenant Nick Graziano Firefighter Stephen Interdonati Chief Fire Marshal Thomas G. Kane Lieutenant Ralph L. Longo Battalion Chief Stephen Marsar EMS Division Chief Paul Miano Firefighter Thomas Morrison Battalion Chief Sean Newman Battalion Chief Anthony Pascocello Lieutenant Stephen Rhine EMT Patricia Scaduto Photo Credits Lieutenant Sean Schneider EMS Lieutenant Linda A. Scott Cover Firefighter William Staudt Bronx Box 77-3072, 1547 Commonwealth Avenue/East Tremont Avenue, January 2, 2018. Lieutenant Jon Templeton Photo by FF Michael Gomez, Squad 288. Firefighter Francis Valerio EMT Michael Walsh Firefighter Daniel W. Gordon, Ladder 47, operated at this incident and is receiving the Company EMS Lieutenant Brandy Washington Officers Association Medal. -

November 13, 2019 Board Members Present Vincent Arcuri, Jr; Antonetta Binanti; Robert Cermeli; Walter E

Minutes of Community Board 5 Public Meeting November 13, 2019 Board Members Present Vincent Arcuri, Jr; Antonetta Binanti; Robert Cermeli; Walter E. Clayton, Jr.; Patricia Crowley; Jerome Drake; Steven Fiedler; Richard Huber; Paul A. Kerzner; Maryann Lattanzio; Edward Lettau; John Maier; Patricia Maltezos; Edgar Mantel; Katherine Masi; Eileen Moloney; Margaret O’Kane; Michael O’Kane; Donald Passantino; Michael Porcelli; Kenneth Rehberger; Theodore Renz; Kelvin Rodriguez; Luis Rodriguez; Connie Santos; Dennis Stephan; Megan Tadio; Gyanal Thapa; Barbara Toscano; Michaeline Von Drathen; Crystal Wolfe; Maryanna Zero; Board Members Absent Brian Dooley; Dmytro Fedkowskyj; Patricia Grayson; Mohan Gyawali-Chhetri; Fred T. Haller; Fred Hoefferle; Mike Liendo; Lee S. Rottenberg; Walter H. Sanchez; Carmen Santana; Catherine Sumsky; Patrick J. Trinchese; Nan Zhang Elected Officials NYS Senator Joseph P. Addabbo, 15th SD and Staff Sarah Spellman NYC Council Member Robert Holden, 30th CD and Staff Charles Vavruska Joseph Nocerino - Queens Borough President Melinda Katz Julio Salazar – U. S. Representative Nydia Velazquez, 7th C.D. Cristian Romero – U. S. Representative Grace Meng, 6th C.D. Kevin Wisniewski – NYS Assemblyman Andrew Hevesi, 28th AD Lesi Hreb - NYS Assemblyman Brian Barnwell, 30th AD Alison Cummings – NYS Assemblywoman Catherine Nolan, 37th AD Christine Stoll – NYS Assemblyman Michael Miller, 38th AD Fatima Elmansy – NYC Council Member Antonio Reynoso, 34th CD Staff Present Gary Giordano, District Manager, CB5 Queens Catherine O’Leary, Community Associate - CB5Q Staff GUESTS Sayaka Kobayashi Prestia, NY Regional Office of US Census Bureau Denise Esposito, CERT Training Coordinator, NYC Office of Emergency Management Theresa Whittlesey, Manager of Community Relations –Forest Hills-L.I.J. Hospital P.O. -

Brooklyn Night Bus

BBrrookkllyynn BBuuss Night Night M Mapap 1:00 AM to 5:00 AM Q 23 St ae E Northern Blvd nq 46 100 Queensboro Plaza CHELSEA 12 28 St 33 St Q n7 23 St Q 66 f MADISON AV Court Sq 39 E Queens Plaza HIGH LINE W 14 ST 23 St 46 7 23 St 65 St EIGHTH AV E E 37 AV 12 28 St HUNTERS 39 AV FEDERAL 36 AV ELEVATED 62 Q Jackson Hts Downtown Brooklyn Court Sq 7 Q Downtown Brooklyn BUILDING LIC / Queens Plaza New Jersey PARK ae L 8 Av 18 St POINT 32 Roosevelt Av 14 St nq G 70 X Q70 SBS E 38 AV 23 St E 34 St / 21 St G Court Sq Q to LaGuardia SBS CADMAN PLAZA WEST 14 St 28 LEXINGTON AV THOMSO 46 ST Midtown 60 Q Q F ED KOCH 12 f Vernon Blvd - WOODSIDE TILLARY ST 14 St SUNNYSIDE 35 ST ROTUNDA East River Ferry Jackson Av N AV LIRR 53 70 Q 46 JACKSON AV YARD 39 ST 6 Av L Hunters Point South / 7 WOODSIDE SBS SBS GALLERY 26 62 66 23 St 42 ST QUEENSBORO BRIDGE UNION Long Island City 52 41 23 ST ST 7 33 St- 7 74 St- SQUARE LIRR Q 7 7 PIERREPONT ST Q BROADWAY E 23 ST WATERSIDE Rawson St 7 Bway East River Ferry HUNTERSPOINT AV 32 69 St Q LONG PARK LIRR 30 PL 100 PLAZA 7 7 40 St 7 52 St 61 St - 38 26 LONG Lowery St Woodside 32 ISLAND ISLAND Hunters SUNNYSIDE 7 Q IRVING PL 3 AV McGUINNESS BLVD Point Av 58 ST BROOKLYN 14 St- 11 ST Q CHRISTOPHER ST SEVENTH AV nql CITY 46 St QUEENS BLVD Q 60 Q 21 ST CITY Union Sq 30 ST HISTORICAL FAMILY QUEENS PLAZA S PETER 39 Bliss St 63 ST 1 2 AV 25 102 ROOSEVELT 101 21 St VAN DAM SOCIETY NY STATE JOHNSON ST F CRESCENT ST Christopher St 12 l 3 Av COOPER Q MONTAGUE ST COURT Queensbridge Sheridan Sq 48 AV 44 AV SUPREME 25 ISLAND VILLAGE -

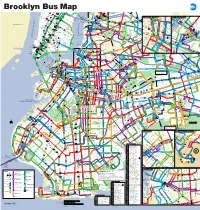

Brooklyn Bus Map

Brooklyn Bus Map To E 5757 StSt 7 7 Q M R C E BM Queensboro N W Northern Blvd Q Q 100 Plaza 23 St 23 St R W 5 5 AV 1 28 St 6 E 34 ST 103 69 Q WEST ST 66 33 St Court Sq 7 7 Q 37 AV Q18 to 444 DR 9 M CHELSEA F M 4 D 3 E E M Queens Astoria R Plaza Q104 to BROADWAY 23 St QUEENS MIDTOWN7 Court Sq - Q 65 St HIGH LINE W 14 S 23 ST 23 St R 7 46 AV 39 AV Astoria 18 M R 37 AV 1 X 6 Q FEDERAL 36 ELEVATED T 32 62 Q Jackson Hts Downtown Brooklyn LIC / Queens Plaza AV 47 AV D Q Downtown Brooklyn BUILDING 67 LIC / Queens Plaza 27 1 T Q PARK 18 St MADISON28 AVSt 32 ST Roosevelt Av 14 St A C E TUNNEL G Court Sq 58 ST 70 R W 67 212 ST 102 E ST 44 Q70 SBS L 8 Av X 28 S Q 6 S E F 38 T 4 TILLARY ST E 34 St / HUNTERSHUNTER BLV21 StSt G SKILLMAN AV SBS 103 AV 28 23 St VERNON to LaGuardia BACABAC F 14 St LEXINGTON AV T THOMSO 0 48 T O 6 Q Q M R ED KOCH Midtown 9 ST Q CADMAN PLAZA F M VernonVe Blvdlvd - 5 ST T 37 S WOODSIDE 1 2 3 14 St 3 LIRRRR 53 70 POINT JaJ cksonckson AvAv SUNNYSIDE S 104 ROTUNDA Q East River Ferry N AV 40 ST Q 2 ST EIGHTH AV 6 JACKSONAV QUEENS BLVD 43 AV NRY S 40 AV Q 3 23 St 4 WOODSIDEOD E TILLARY ST L 7 7 LIRR YARD SBS SBS 32 GALLERY 26 H N 66 23 Hunters Point South / 46 St T AV HE 52 41 QUEENSBORO 9 UNION E 23 ST M 7 L R 6 BROADWAY BRIDGEB U 6 Av HUNTERSPOINT AV 7 33 St- Bliss St E 7 Q32 E Long Island City A 7 7 69 St to 7 PIERREPONT ST W Q SQUARE Rawson St WOOD 69 ST 62 57 D WATERSIDE 49 AV T ROOSEV 61 St - Jackson G Q Q T 74 St- LONG East River Ferry T LIRR 100 PARK S ST 7 T Woodside Bway PARK AV S S 7 40 St S Heights 103 1 38 26 PLAZA