For Review Only Journal: Popular Narrative Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

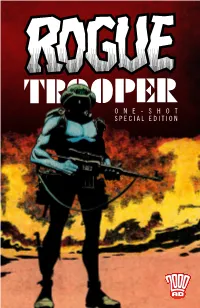

One-Shot Special Edition Script Gerry Finley-Day Guy Adams Art Dave Gibbons Darren Douglas Lee Carter Letters Simon Bowland Dave Gibbons

ONE-SHOT SPECIAL EDITION SCRIPT GERRY FINLEY-DAY GUY ADAMS ART DAVE GIBBONS DARREN DOUGLAS LEE CARTER LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND DAVE GIBBONS REBELLION Creative Director and CEO Junior Graphic Novels Editor JASON KINGSLEY OLIVER BALL Chief Technical Officer Graphic Design CHRIS KINGSLEY SAM GRETTON, OZ OSBORNE & MAZ SMITH Head of Books & Comics Reprographics BEN SMITH JOSEPH MORGAN 2000 AD Editor in Chief PR & Marketing MATT SMITH MICHAEL MOLCHER Graphic Novels Editor Publishing Assistant KEITH RICHARDSON OWEN JOHNSON Rogue Trooper Published by Rebellion, Riverside House, Osney Mead, Oxford OX2 0ES. All contents © 1981, 2014, 2015, 2018 Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. All rights reserved. Rogue Trooper is a trademark of Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. Reproduction, storage in a retrieval system or transmission in any form or by any means in whole or part without prior permission of Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. is strictly forbidden. No similarity between any of the fictional names, characters, persons and/or institutions herein with those of any living or dead persons or institutions is intended (except for satirical purposes) and any such similarity is purely coincidental. ROGUE TROOPER SCRIPT GERRY FINLEY-DAY ART DAVE GIBBONS LETTERS DAVE GIBBONS ROGUE TROOPER DREGS OF WAR SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART DARREN DOUGLAS LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND ROGUE TROOPER THE FEAST SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART LEE CARTER LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND ROGUE TROOPER THE DEATH OF A DEMON SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART DARREN DOUGLAS LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND THE END ROGUE TROOPER GRAPHIC NOVELS FROM 2000 AD ROGUE TROOPER ROGUE -

Twisted Trails of the Wold West by Matthew Baugh © 2006

Twisted Trails of the Wold West By Matthew Baugh © 2006 The Old West was an interesting place, and even more so in the Wold- Newton Universe. Until fairly recently only a few of the heroes and villains who inhabited the early western United States had been confirmed through crossover stories as existing in the WNU. Several comic book miniseries have done a lot to change this, and though there are some problems fitting each into the tapestry of the WNU, it has been worth the effort. Marvel Comics’ miniseries, Rawhide Kid: Slap Leather was a humorous storyline, parodying the Kid’s established image and lampooning westerns in general. It is best known for ‘outing’ the Kid as a homosexual. While that assertion remains an open issue with fans, it isn’t what causes the problems with incorporating the story into the WNU. What is of more concern are the blatant anachronisms and impossibilities the story offers. We can accept it, but only with the caveat that some of the details have been distorted for comic effect. When the Rawhide Kid is established as a character in the Wold-Newton Universe he provides links to a number of other western characters, both from the Marvel Universe and from classic western novels and movies. It draws in the Marvel Comics series’ Blaze of Glory, Apache Skies, and Sunset Riders as wall as DC Comics’ The Kents. As with most Marvel and DC characters there is the problem with bringing in the mammoth superhero continuities of the Marvel and DC universes, though this is not insurmountable. -

Graphic Novel Titles

Comics & Libraries : A No-Fear Graphic Novel Reader's Advisory Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives February 2017 Beginning Readers Series Toon Books Phonics Comics My First Graphic Novel School Age Titles • Babymouse – Jennifer & Matthew Holm • Squish – Jennifer & Matthew Holm School Age Titles – TV • Disney Fairies • Adventure Time • My Little Pony • Power Rangers • Winx Club • Pokemon • Avatar, the Last Airbender • Ben 10 School Age Titles Smile Giants Beware Bone : Out from Boneville Big Nate Out Loud Amulet The Babysitters Club Bird Boy Aw Yeah Comics Phoebe and Her Unicorn A Wrinkle in Time School Age – Non-Fiction Jay-Z, Hip Hop Icon Thunder Rolling Down the Mountain The Donner Party The Secret Lives of Plants Bud : the 1st Dog to Cross the United States Zombies and Forces and Motion School Age – Science Titles Graphic Library series Science Comics Popular Adaptations The Lightning Thief – Rick Riordan The Red Pyramid – Rick Riordan The Recruit – Robert Muchamore The Nature of Wonder – Frank Beddor The Graveyard Book – Neil Gaiman Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children – Ransom Riggs House of Night – P.C. Cast Vampire Academy – Richelle Mead Legend – Marie Lu Uglies – Scott Westerfeld Graphic Biographies Maus / Art Spiegelman Anne Frank : the Anne Frank House Authorized Graphic Biography Johnny Cash : I See a Darkness Peanut – Ayun Halliday and Paul Hope Persepolis / Marjane Satrapi Tomboy / Liz Prince My Friend Dahmer / Derf Backderf Yummy : The Last Days of a Southside Shorty -

Growing up with Vertigo: British Writers, Dc, and the Maturation of American Comic Books

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by ScholarWorks @ UVM GROWING UP WITH VERTIGO: BRITISH WRITERS, DC, AND THE MATURATION OF AMERICAN COMIC BOOKS A Thesis Presented by Derek A. Salisbury to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in History May, 2013 Accepted by the Faculty of the Graduate College, The University of Vermont, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, specializing in History. Thesis Examination Committee: ______________________________________ Advisor Abigail McGowan, Ph.D ______________________________________ Melanie Gustafson, Ph.D ______________________________________ Chairperson Elizabeth Fenton, Ph.D ______________________________________ Dean, Graduate College Domenico Grasso, Ph.D March 22, 2013 Abstract At just under thirty years the serious academic study of American comic books is relatively young. Over the course of three decades most historians familiar with the medium have recognized that American comics, since becoming a mass-cultural product in 1939, have matured beyond their humble beginnings as a monthly publication for children. However, historians are not yet in agreement as to when the medium became mature. This thesis proposes that the medium’s maturity was cemented between 1985 and 2000, a much later point in time than existing texts postulate. The project involves the analysis of how an American mass medium, in this case the comic book, matured in the last two decades of the twentieth century. The goal is to show the interconnected relationships and factors that facilitated the maturation of the American sequential art, specifically a focus on a group of British writers working at DC Comics and Vertigo, an alternative imprint under the financial control of DC. -

Mason 2015 02Thesis.Pdf (1.969Mb)

‘Page 1, Panel 1…” Creating an Australian Comic Book Series Author Mason, Paul James Published 2015 Thesis Type Thesis (Professional Doctorate) School Queensland College of Art DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/3741 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367413 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au ‘Page 1, Panel 1…” Creating an Australian Comic Book Series Paul James Mason s2585694 Bachelor of Arts/Fine Art Major Bachelor of Animation with First Class Honours Queensland College of Art Arts, Education and Law Group Griffith University Submitted in fulfillment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Visual Arts (DVA) June 2014 Abstract: What methods do writers and illustrators use to visually approach the comic book page in an American Superhero form that can be adapted to create a professional and engaging Australian hero comic? The purpose of this research is to adapt the approaches used by prominent and influential writers and artists in the American superhero/action comic-book field to create an engaging Australian hero comic book. Further, the aim of this thesis is to bridge the gap between the lack of academic writing on the professional practice of the Australian comic industry. In order to achieve this, I explored and learned the methods these prominent and professional US writers and artists use. Compared to the American industry, the creating of comic books in Australia has rarely been documented, particularly in a formal capacity or from a contemporary perspective. The process I used was to navigate through the research and studio practice from the perspective of a solo artist with an interest to learn, and to develop into an artist with a firmer understanding of not only the medium being engaged, but the context in which the medium is being created. -

British Writers, DC, and the Maturation of American Comic Books Derek Salisbury University of Vermont

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2013 Growing up with Vertigo: British Writers, DC, and the Maturation of American Comic Books Derek Salisbury University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Recommended Citation Salisbury, Derek, "Growing up with Vertigo: British Writers, DC, and the Maturation of American Comic Books" (2013). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 209. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/209 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GROWING UP WITH VERTIGO: BRITISH WRITERS, DC, AND THE MATURATION OF AMERICAN COMIC BOOKS A Thesis Presented by Derek A. Salisbury to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in History May, 2013 Accepted by the Faculty of the Graduate College, The University of Vermont, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, specializing in History. Thesis Examination Committee: ______________________________________ Advisor Abigail McGowan, Ph.D ______________________________________ Melanie Gustafson, Ph.D ______________________________________ Chairperson Elizabeth Fenton, Ph.D ______________________________________ Dean, Graduate College Domenico Grasso, Ph.D March 22, 2013 Abstract At just under thirty years the serious academic study of American comic books is relatively young. Over the course of three decades most historians familiar with the medium have recognized that American comics, since becoming a mass-cultural product in 1939, have matured beyond their humble beginnings as a monthly publication for children. -

The 2000 AD Script Book Kindle

THE 2000 AD SCRIPT BOOK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Pat Mills, John Wagner, Peter Milligan, Al Ewing, Rob Williams, Dan Abnett, Emma Beeby, Gordon Rennie, Ian Edginton, Alan Grant | 192 pages | 03 Nov 2016 | Rebellion | 9781781084670 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom The 2000 AD Script Book PDF Book And there's a bunch of other properties out with film companies. He was supported by bio-chips of the personalities of three dead comrades, which, slotted into his equipment, could talk to him. Would it be safe to say that you have contributed more material to " AD" than any other writer? Retrieved 10 May All that was seen of Nemesis was the outside of his vehicle, the Blitzspear. However, the fanzine's genesis was plagued by bad luck, not least of all Dick's health worsening. It's gone down very well with readers. There were also gimmicks, like the "sex issue", sold in a clear plastic wrapper, The Spacegirls , a series attempting to cash in on the popularity of the Spice Girls , B. His real task? The last issue titled AD and Tornado was prog , dated 13 September Films Hardware Judge Dredd Dredd. Tweet Clean. Paradoxically, I owe my "Requiem's" success to them. In addition, there are interviews with leading writers and artists, and each issue includes a bonus page graphic novel every month, featuring material from the AD archive! Cover of the first issue of AD , 26 February I kept it going until various story threads were resolved, which took longer than I anticipated. Featuring original script drafts and the final published artwork for comparison, this is a must have for fans of AD and those interested in the writing process. -

Asfacts Feb16.Pub

ASFACTS 2016 FEBRUARY “S PACE ODDITY ” V ALENTINE ISSUE ♥ ♥ ♥ ♥ ♥ ♥ ♥ ♥ ♥ ♥ ♥ ♥ ♥ ♥ ♥ ♥ ♥ ♥ are free of charge. These panels are sure to provide a wide ENMU WILLIAMSON LECTURESHIP range of topics and free-wheeling discussion and debate between panelists and audience. SCHEDULED FOR FRIDAY , A PRIL 8 On Saturday, April 9, a Writers Workshop for aspir- ing young writers is planned 10:00 am-Noon at the Por- The 40th annual Jack Williamson Lectureship will be tales Public Library with Connie Willis and Steven held Friday, April 8, at Eastern New Mexico University in Gould. Interested participants can contact the Portales Portales, NM. Special guests are Albuquerque’s Victor Library, 218 S Avenue B, in Portales, at (575) 356-3940. Milán and Mistress of Ceremonies Connie Willis (of For more information, contact Caldwell by phone or Colorado). Friday events include Milan’s reading, a email her at [email protected]. luncheon and various panel discussions. A campus tradition since 1977, the Lectureship annu- ND ally draws well-known authors to visit the ENMU campus EXPANSE GETS 2 SEASON and discuss the interactions of science and the humanities. Williamson, long-time SF author and professor of Syfy has given a second season to The Expanse and is English passed away in 2006. Williamson’s novella, “The increasing the episode order from 10 to 13 for the futuris- Ultimate Earth,” won a 2001 Hugo Award, and his last tic mystery’s sophomore turn, Variety.com posted at the novel, The Stonehenge Gate , was released in 2005. end of December. Milán is the author of more than 60 novels, including The Alcon Television Group series gained traction last year’s The Dinosaur Lords and this year’s sequel, The from an online debut last November that brought in 4.5 million viewers before its official premiere on December Dinosaur Knights (to be released in July). -

Punisher Max: Frank Free

FREE PUNISHER MAX: FRANK PDF Jason Aaron,Steve Dillon | 112 pages | 31 Dec 2016 | Marvel Comics | 9780785152095 | English | New York, United States PunisherMAX, Vol. 3: Frank by Jason Aaron Born in and grew up in BrooklynFrank was a serious boy who enjoyed poetry. At the age of ten he witnessed one of the events that would form his future as the Punisher. The youngest son of a local crime boss named Albert RosaVincent Rosa made a habit of raping the local young school girls knowing that his father's power over the people around him would ensure his safety. It wasn't until a school friend of Frank's, Lauren Buvoli was given the same treatment and committed suicide, that Frank took his father's gun Punisher Max: Frank set out to deal with Punisher Max: Frank. However, after tracking Vincent down he witnessed his brutal murder at the hands of Lauren's older brother, U. Marine Private Sal Buvoli whose dead body Castle would later see in the first week of his military service. At some point in his young life Castle's father Mario taught him how to shoot him a gun which he showed Punisher Max: Frank innate skill with from his very first shot. Frank later spent four years of his life in the Vietnam War. His first tour began in when he enlisted in the marine corps after the birth of his first child so that his wife and daughter could afford to live in a home and not the apartment they had been living in in a dangerous part of Brooklynshortly before he enlisted his father died. -

Moore Layout Original

Bibliography Within your dictionary, next to word “prolific” you’ll created with their respective co-creators/artists) printing of this issue was pulped by DC hierarchy find a photo of Alan Moore – who since his profes - because of a Marvel Co. feminine hygiene product ad. AMERICA’S BEST COMICS 64 PAGE GIANT – Tom sional writing debut in the late Seventies has written A few copies were saved from the company’s shred - Strong “Skull & Bones” – Art: H. Ramos & John hundreds of stories for a wide range of publications, der and are now costly collectibles) Totleben / “Jack B. Quick’s Amazing World of both in the United States and the UK, from child fare Science Part 1” – Art: Kevin Nowlan / Top Ten: THE LEAGUE OF EXTRAORDINARY GENTLEMEN like Star Wars to more adult publications such as “Deadfellas” – Art: Zander Cannon / “The FIRST (Volume One) #6 – “6: The Day of Be With Us” & Knave . We’ve organized the entries by publishers and First American” – Art: Sergio Aragonés / “The “Chapter 6: Allan and the Sundered Veil’s The listed every relevant work (comics, prose, articles, League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen Game” – Art: Awakening” – Art: Kevin O’Neill – 1999 artwork, reviews, etc...) written by the author accord - Kevin O’Neill / Splash Brannigan: “Specters from ingly. You’ll also see that I’ve made an emphasis on THE LEAGUE OF EXTRAORDINARY GENTLEMEN Projectors” – Art: Kyle Baker / Cobweb: “He Tied mentioning the title of all his penned stories because VOLUME 1 – Art: Kevin O’Neill – 2000 (Note: Me To a Buzzsaw (And It Felt Like a Kiss)” – Art: it is a pet peeve of mine when folks only remember Hardcover and softcover feature compilation of the Dame Darcy / “Jack B. -

FRANK CASTLE Was a Decorated Marine, an Upstanding Citizen, and a Family Man. Then His Family Was Taken from Him When They Were

FRANK CASTLE was a decorated Marine, an upstanding citizen, and a family man. Then his family was taken from him when they were accidentally killed in a brutal mob hit. From that day, he became a force of cold, calculated retribution and vigilantism. Frank Castle died with his family. Now, there is only… What should have been a typical drug warehouse raid for the Punisher went sideways when the drug, EMC-- which gives its users enhanced strength, reflexes, and insensitivity to pain--enabled the criminals to fight back. The Punisher neutralized everyone in the warehouse except Olaf, a disgruntled member of Condor (mercenary outfit turned drug cartel) and old Marine buddy of Frank’s. Olaf escaped Frank, but left a guide to Condor’s drug operation for the Punisher to follow. Good for Frank, bad for D.E.A. Agent Ortiz’s case against Condor, as you can’t prosecute corpses. And there will be corpses aplenty, as Condor’s hatchet man, Face, now has Punisher in his sights. WRITER ARTIST COLOR ARTIST BECKY CLOONAN STEVE DILLON FRANK MARTIN LETTERER COVER ARTISTS VARIANT COVER ARTIST VC’S CORY PETIT DECLAN SHALVEY AND VANESA DEL REY JORDIE BELLAIRE ASSISTANT EDITOR EDITOR KATHLEEN WISNESKI JAKE THOMAS EDITOR IN CHIEF CHIEF CREATIVE OFFICER PUBLISHER EXECUTIVE PRODUCER AXEL ALONSO JOE QUESADA DAN BUCKLEY ALAN FINE THE PUNISHER No. 2, August 2016. Published Monthly by MARVEL WORLDWIDE, INC., a subsidiary of MARVEL ENTERTAINMENT, LLC. OFFICE OF PUBLICATION: 135 West 50th Street, New York, NY 10020. BULK MAIL POSTAGE PAID AT NEW YORK, NY AND AT ADDITIONAL MAILING OFFICES. -

Marvel January – April 2021

MARVEL Aero Vol. 2 The Mystery of Madame Huang Zhou Liefen, Keng Summary THE MADAME OF MYSTERY AND MENACE! LEI LING finally faces MADAME HUANG! But who is Huang, and will her experience and power stop AERO in her tracks? And will Aero be able to crack the mystery of the crystal jade towers and creatures infiltrating Shanghai before they take over the city? COLLECTING: AERO (2019) 7-12 Marvel 9781302919450 Pub Date: 1/5/21 On Sale Date: 1/5/21 $17.99 USD/$22.99 CAD Paperback 136 Pages Carton Qty: 40 Ages 13 And Up, Grades 8 to 17 Comics & Graphic Novels / Superheroes CGN004080 Captain America: Sam Wilson - The Complete Collection Vol. 2 Nick Spencer, Daniel Acuña, Angel Unzueta, Paul Re... Summary Sam Wilson takes flight as the soaring Sentinel of Liberty - Captain America! Handed the shield by Steve Rogers himself, the former Falcon is joined by new partner Nomad to tackle threats including the fearsome Scarecrow, Batroc and Baron Zemo's newly ascendant Hydra! But stepping into Steve's boots isn't easy -and Sam soon finds himself on the outs with both his old friend and S.H.I.E.L.D.! Plus, the Sons of the Serpent, Doctor Malus -and the all-new Falcon! And a team-up with Spider-Man and the Inhumans! The headline- making Sam Wilson is a Captain America for today! COLLECTING: CAPTAIN AMERICA (2012) 25, ALL-NEW CAPTAIN AMERICA: FEAR HIM (2015) 1-4, ALL-NEW CAPTAIN AMERICA (2014) 1-6, AMAZING SPIDERMAN SPECIAL (2015) 1, INHUMAN SPECIAL (2015) 1, Marvel ALL-NEW CAPTAIN AMERICA SPECIAL (2015) 1, CAPTAIN AMERICA: SAM WILSON (2015) 1-6 9781302922979 Pub Date: 1/5/21 On Sale Date: 1/5/21 $39.99 USD/$49.99 CAD Paperback 504 Pages Carton Qty: 40 Ages 13 And Up, Grades 8 to 17 Comics & Graphic Novels / Superheroes CGN004080 Marvel January to April 2021 - Page 1 MARVEL Guardians of the Galaxy by Donny Cates Donny Cates, Al Ewing, Tini Howard, Zac Thompson, ..