Soft Innovation Towards a More Complete Picture of Innovative Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Video Game Trader Magazine & Price Guide

Winter 2009/2010 Issue #14 4 Trading Thoughts 20 Hidden Gems Blue‘s Journey (Neo Geo) Video Game Flashback Dragon‘s Lair (NES) Hidden Gems 8 NES Archives p. 20 19 Page Turners Wrecking Crew Vintage Games 9 Retro Reviews 40 Made in Japan Coin-Op.TV Volume 2 (DVD) Twinkle Star Sprites Alf (Sega Master System) VectrexMad! AutoFire Dongle (Vectrex) 41 Video Game Programming ROM Hacking Part 2 11Homebrew Reviews Ultimate Frogger Championship (NES) 42 Six Feet Under Phantasm (Atari 2600) Accessories Mad Bodies (Atari Jaguar) 44 Just 4 Qix Qix 46 Press Start Comic Michael Thomasson’s Just 4 Qix 5 Bubsy: What Could Possibly Go Wrong? p. 44 6 Spike: Alive and Well in the land of Vectors 14 Special Book Preview: Classic Home Video Games (1985-1988) 43 Token Appreciation Altered Beast 22 Prices for popular consoles from the Atari 2600 Six Feet Under to Sony PlayStation. Now includes 3DO & Complete p. 42 Game Lists! Advertise with Video Game Trader! Multiple run discounts of up to 25% apply THIS ISSUES CONTRIBUTORS: when you run your ad for consecutive Dustin Gulley Brett Weiss Ad Deadlines are 12 Noon Eastern months. Email for full details or visit our ad- Jim Combs Pat “Coldguy” December 1, 2009 (for Issue #15 Spring vertising page on videogametrader.com. Kevin H Gerard Buchko 2010) Agents J & K Dick Ward February 1, 2009(for Issue #16 Summer Video Game Trader can help create your ad- Michael Thomasson John Hancock 2010) vertisement. Email us with your requirements for a price quote. P. Ian Nicholson Peter G NEW!! Low, Full Color, Advertising Rates! -

Newagearcade.Com 5000 in One Arcade Game List!

Newagearcade.com 5,000 In One arcade game list! 1. AAE|Armor Attack 2. AAE|Asteroids Deluxe 3. AAE|Asteroids 4. AAE|Barrier 5. AAE|Boxing Bugs 6. AAE|Black Widow 7. AAE|Battle Zone 8. AAE|Demon 9. AAE|Eliminator 10. AAE|Gravitar 11. AAE|Lunar Lander 12. AAE|Lunar Battle 13. AAE|Meteorites 14. AAE|Major Havoc 15. AAE|Omega Race 16. AAE|Quantum 17. AAE|Red Baron 18. AAE|Ripoff 19. AAE|Solar Quest 20. AAE|Space Duel 21. AAE|Space Wars 22. AAE|Space Fury 23. AAE|Speed Freak 24. AAE|Star Castle 25. AAE|Star Hawk 26. AAE|Star Trek 27. AAE|Star Wars 28. AAE|Sundance 29. AAE|Tac/Scan 30. AAE|Tailgunner 31. AAE|Tempest 32. AAE|Warrior 33. AAE|Vector Breakout 34. AAE|Vortex 35. AAE|War of the Worlds 36. AAE|Zektor 37. Classic Arcades|'88 Games 38. Classic Arcades|1 on 1 Government (Japan) 39. Classic Arcades|10-Yard Fight (World, set 1) 40. Classic Arcades|1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 41. Classic Arcades|18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 42. Classic Arcades|1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Classic Arcades|1942 (Revision B) 44. Classic Arcades|1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 45. Classic Arcades|1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 46. Classic Arcades|1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 47. Classic Arcades|1945k III 48. Classic Arcades|19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 49. Classic Arcades|2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 50. Classic Arcades|2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 51. -

Full Games List Pandora DX 3000 in 1

www.myarcade.com.au Ph 0412227168 Full Games List Pandora DX 3000 in 1 1. 10-YARD FIGHT – (1/2P) – (1464) 38. ACTION 52 – (1/2P) – (2414) 2. 16 ZHANG MA JIANG – (1/2P) – 39. ACTION FIGHTER – (1/2P) – (1093) (2391) 40. ACTION HOLLYWOOOD – (1/2P) – 3. 1941 : COUNTER ATTACK – (1/2P) – (362) (860) 41. ADDAMS FAMILY VALUES – (1/2P) – 4. 1942 – (1/2P) – (861) (2431) 5. 1942 – AIR BATTLE – (1/2P) – (1140) 42. ADVENTUROUS BOY-MAO XIAN 6. 1943 : THE BATTLE OF MIDWAY – XIAO ZI – (1/2P) – (2266) (1/2P) – (862) 43. AERO FIGHTERS – (1/2P) – (927) 7. 1943 KAI : MIDWAY KAISEN – (1/2P) 44. AERO FIGHTERS 2 – (1/2P) – (810) – (863) 45. AERO FIGHTERS 3 – (1/2P) – (811) 8. 1943: THE BATTLE OF MIDWAY – 46. AERO FIGHTERS 3 BOSS – (1/2P) – (1/2P) – (1141) (812) 9. 1944 : THE LOOP MASTER – (1/2P) 47. AERO FIGHTERS- UNLIMITED LIFE – (780) – (1/2P) – (2685) 10. 1945KIII – (1/2P) – (856) 48. AERO THE ACRO-BAT – (1/2P) – 11. 19XX : THE WAR AGAINST DESTINY (2222) – (1/2P) – (864) 49. AERO THE ACRO-BAT 2 – (1/2P) – 12. 2 ON 2 OPEN ICE CHALLENGE – (2624) (1/2P) – (1415) 50. AERO THE ACRO-BAT 2 (USA) – 13. 2020 SUPER BASEBALL – (1/2P) – (1/2P) – (2221) (1215) 51. AFTER BURNER II – (1/2P) – (1142) 14. 3 COUNT BOUT – (1/2P) – (1312) 52. AGENT SUPER BOND – (1/2P) – 15. 4 EN RAYA – (1/2P) – (1612) (2022) 16. 4 FUN IN 1 – (1/2P) – (965) 53. AGGRESSORS OF DARK KOMBAT – 17. 46 OKUNEN MONOGATARI – (1/2P) (1/2P) – (106) – (2711) 54. -

Download 80 PLUS 4983 Horizontal Game List

4 player + 4983 Horizontal 10-Yard Fight (Japan) advmame 2P 10-Yard Fight (USA, Europe) nintendo 1941 - Counter Attack (Japan) supergrafx 1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) mame172 2P sim 1942 (Japan, USA) nintendo 1942 (set 1) advmame 2P alt 1943 Kai (Japan) pcengine 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) mame172 2P sim 1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) mame172 2P sim 1943 - The Battle of Midway (USA) nintendo 1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) mame172 2P sim 1945k III advmame 2P sim 19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) mame172 2P sim 2010 - The Graphic Action Game (USA, Europe) colecovision 2020 Super Baseball (set 1) fba 2P sim 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) mame078 4P sim 36 Great Holes Starring Fred Couples (JU) (32X) [!] sega32x 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex (NGM-043)(NGH-043) fba 2P sim 3D Crazy Coaster vectrex 3D Mine Storm vectrex 3D Narrow Escape vectrex 3-D WorldRunner (USA) nintendo 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) [!] megadrive 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) supernintendo 4-D Warriors advmame 2P alt 4 Fun in 1 advmame 2P alt 4 Player Bowling Alley advmame 4P alt 600 advmame 2P alt 64th. Street - A Detective Story (World) advmame 2P sim 688 Attack Sub (UE) [!] megadrive 720 Degrees (rev 4) advmame 2P alt 720 Degrees (USA) nintendo 7th Saga supernintendo 800 Fathoms mame172 2P alt '88 Games mame172 4P alt / 2P sim 8 Eyes (USA) nintendo '99: The Last War advmame 2P alt AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (E) [!] supernintendo AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (UE) [!] megadrive Abadox - The Deadly Inner War (USA) nintendo A.B. -

3 Ninjas Kick Back 688 Attack Sub 6-Pak Aaahh!!! Real

3 NINJAS KICK BACK 688 ATTACK SUB 6-PAK AAAHH!!! REAL MONSTERS ACTION 52 ADDAMS FAMILY VALUES THE ADDAMS FAMILY ADVANCED BUSTERHAWK GLEYLANCER ADVANCED DAISENRYAKU - DEUTSCH DENGEKI SAKUSEN THE ADVENTURES OF BATMAN & ROBIN THE ADVENTURES OF MIGHTY MAX THE ADVENTURES OF ROCKY AND BULLWINKLE AND FRIENDS AERO THE ACRO-BAT AERO THE ACRO-BAT 2 AEROBIZ AEROBIZ SUPERSONIC AFTER BURNER II AIR BUSTER AIR DIVER ALADDIN ALADDIN II ALEX KIDD IN THE ENCHANTED CASTLE ALIEN 3 ALIEN SOLDIER ALIEN STORM ALISIA DRAGOON ALTERED BEAST AMERICAN GLADIATORS ANDRE AGASSI TENNIS ANIMANIACS THE AQUATIC GAMES STARRING JAMES POND AND THE AQUABATS ARCADE CLASSICS ARCH RIVALS - THE ARCADE GAME ARCUS ODYSSEY ARIEL THE LITTLE MERMAID ARNOLD PALMER TOURNAMENT GOLF ARROW FLASH ART ALIVE ART OF FIGHTING ASTERIX AND THE GREAT RESCUE ASTERIX AND THE POWER OF THE GODS ATOMIC ROBO-KID ATOMIC RUNNER ATP TOUR CHAMPIONSHIP TENNIS AUSTRALIAN RUGBY LEAGUE AWESOME POSSUM... ...KICKS DR. MACHINO'S BUTT AYRTON SENNA'S SUPER MONACO GP II B.O.B. BABY BOOM (PROTO) BABY'S DAY OUT (PROTO) BACK TO THE FUTURE PART III BALL JACKS BALLZ 3D - FIGHTING AT ITS BALLZIEST ~ BALLZ 3D - THE BATTLE OF THE BALLZ BARBIE SUPER MODEL BARBIE VACATION ADVENTURE (PROTO) BARE KNUCKLE - IKARI NO TETSUKEN ~ STREETS OF RAGE BARE KNUCKLE III BARKLEY SHUT UP AND JAM 2 BARKLEY SHUT UP AND JAM! BARNEY'S HIDE & SEEK GAME BARVER BATTLE SAGA - TAI KONG ZHAN SHI BASS MASTERS CLASSIC - PRO EDITION BASS MASTERS CLASSIC BATMAN - REVENGE OF THE JOKER BATMAN - THE VIDEO GAME BATMAN FOREVER BATMAN RETURNS BATTLE GOLFER YUI -

Full Arcade List OVER 2700 ARCADE CLASSICS 1

Full Arcade List OVER 2700 ARCADE CLASSICS 1. 005 54. Air Inferno 111. Arm Wrestling 2. 1 on 1 Government 55. Air Rescue 112. Armed Formation 3. 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles 56. Airwolf 113. Armed Police Batrider Rally 57. Ajax 114. Armor Attack 4. 10-Yard Fight 58. Aladdin 115. Armored Car 5. 18 Holes Pro Golf 59. Alcon/SlaP Fight 116. Armored Warriors 6. 1941: Counter Attack 60. Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars 117. Art of Fighting / Ryuuko no 7. 1942 61. Ali Baba and 40 Thieves Ken 8. 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen 62. Alien Arena 118. Art of Fighting 2 / Ryuuko no 9. 1943: The Battle of Midway 63. Alien Challenge Ken 2 10. 1944: The LooP Master 64. Alien Crush 119. Art of Fighting 3 - The Path of 11. 1945k III 65. Alien Invaders the Warrior / Art of Fighting - 12. 19XX: The War Against Destiny 66. Alien Sector Ryuuko no Ken Gaiden 13. 2 On 2 OPen Ice Challenge 67. Alien Storm 120. Ashura Blaster 14. 2020 SuPer Baseball 68. Alien Syndrome 121. ASO - Armored Scrum Object 15. 280-ZZZAP 69. Alien vs. Predator 122. Assault 16. 3 Count Bout / Fire SuPlex 70. Alien3: The Gun 123. Asterix 17. 30 Test 71. Aliens 124. Asteroids 18. 3-D Bowling 72. All American Football 125. Asteroids Deluxe 19. 4 En Raya 73. Alley Master 126. Astra SuPerStars 20. 4 Fun in 1 74. Alligator Hunt 127. Astro Blaster 21. 4-D Warriors 75. AlPha Fighter / Head On 128. Astro Chase 22. 64th. Street - A Detective Story 76. -

GAME NAME 1941 1942 1943 1944 102 Dalmatians 3D 1941J Set1

GAME NAME 1941 1942 1943 1944 102 Dalmatians 3D 1941j set1 1941j set2 1942h 1943b 1943Kai 1944j 19XX 19xxj 2020 Super Baseball 3 Count Bout 3 Count Bout 3 Ninjas Kick Back 3stooges 3x3 Eyes-Juuma Houkan 4 Fun in 1 4 Fun in 1 40love 4-D Warriors 4-D Warriors 4-nin Shougi 64Th Street 64Th Street 6-Pak 76 in 1 88games 8ballac 90 Tank 96ZenkokuKoukouSoccerSenshuken Aaahh! Real Monsters AAAHH!!! Real Monsters Aburner2 Ace wo Nerae Acrobat Mission Acrobat Mission Acrobat Mission Act-Fancer Actfancrj Actfancrj Action 52 Action bass 3D Action Fighter Action Fighter Action Pachio ActRaiser ActRaiser 2 Addams Family Addams Family(USA) Adventures of Batman-Robin Adventures of TomSawyer Adventures of Yogi Bear Adventurous Boy-MaoXianXiaoZi Aero Blasters Aero Fighters Aero Fighters (USA) Aero Fighters 2 Aero Fighters 3 Aero the Acro-Bat Aero the Acro-Bat (USA) Aero the Acro-Bat 2 Aero the Acro-Bat 2 (USA) Aerobiz (USA) Aerobiz Supersonic (USA) After Burner II Aguri Suzuki F1 SuperDriving Air Attack Air Buster Air Buster: Trouble Specialty Raid Unit Air Cavalry Air Gallet Air galletj set1 Air galletj set2 Airbustrj Airbustrj Airduel Airwolf Ajax Akumajou Dracula Akumajou Dracula XX Albert Odyssey Albert Odyssey 2 ALCAHEST Alex Kidd Alex Kidd Alex Kidd in the Enchanted Castle Alfred Chicken Ali Baba and 40 Thieves Alice no Paint Adventure Alien 3 Alien Soldier Alien Storm Alien Storm 2 Alien Storm 2 Alien Syndrome Alien Syndrome Alien vs Predator Alien Vs. Predator Alien Vs. Predator (3P) Alienchac Aliens Aliens Aliens Aliens vs Predator (Japan) Alisia -

Esports from Wild West to Mainstream

26 June 2018 | 4:01AM EDT eSports From Wild West to Mainstream eSports are moving into the mainstream. The immense popularity of survival-based Christopher D. Merwin, CFA +1(212)357-9336 | games like Fortnite, growing prize pools for eSports tournaments, the rise of [email protected] Goldman Sachs & Co. LLC live-streaming, and improving infrastructure for pro leagues have all paved the way Masaru Sugiyama for eSports to reach nearly 300mn viewers by 2022, on par with NFL viewership +81(3)6437-4691 | [email protected] today. For game publishers, we believe eSports will not only help to increase Goldman Sachs Japan Co., Ltd. audience reach and engagement, but also drive direct revenue through established Piyush Mubayi +852-2978-1677 | [email protected] leagues. We see further tailwinds to the broader eSports ecosystem—including Goldman Sachs (Asia) L.L.C. online video platforms, hardware manufacturers (core and peripheral), and chip Toshiya Hari +1(646)446-1759 | [email protected] makers—opportunities we outline in this report. Goldman Sachs & Co. LLC Heath P. Terry, CFA +1(212)357-1849 | [email protected] Goldman Sachs & Co. LLC Alexander Duval +44(20)7552-2995 | [email protected] Goldman Sachs International Heather Bellini, CFA +1(212)357-7710 | [email protected] Goldman Sachs & Co. LLC Drew Borst +1(212)902-7906 | [email protected] Goldman Sachs & Co. LLC Lisa Yang +44(20)7552-3713 | [email protected] Goldman Sachs International Donald Lu, Ph.D. For the exclusive use of [email protected] +86(10)6627-3123 | [email protected] Beijing Gao Hua Securities Company Limited Garrett Clark +1(212)357-4481 | [email protected] Goldman Sachs & Co. -

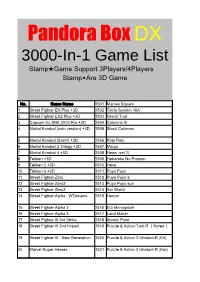

Pandora Box DX 3000-In-1 Games List

Pandora Box DX 3000-In-1 Game List Stamp★Game Support 3Players/4Players Stamp▲Are 3D Game No. Game Name 1501 Maniac Square 1 Street Fighter EX Plus ▲3D 1502 Tetris-System 16A 2 Street Fighter EX2 Plus ▲3D 1503 Grand Tour 3 Capcom Vs.SNK 2000 Pro ▲3D 1504 Columns III 4 Mortal Kombat (coin version) ▲3D 1505 Stack Columns 5 Mortal Kombat 2(set1) ▲3D 1506 Poto Poto 6 Mortal Kombat 3 Trilogy ▲3D 1507 Mouja 7 Mortal Kombat 4 ▲3D 1508 News (set 1) 8 Tekken ▲3D 1509 Hebereke No Popoon 9 Tekken 2 ▲3D 1510 Hexa 10 Tekken 3 ▲3D 1511 Puyo Puyo 11 Street Fighter Zero 1512 Puyo Puyo 2 12 Street Fighter Zero2 1513 Puyo Puyo sun 13 Street Fighter Zero3 1514 Xor World 14 Street Fighter Alpha : W'Dreams 1515 Hexion 15 Street Fighter Alpha 2 1516 Eto Monogatari 16 Street Fighter Alpha 3 1517 Land Maker 17 Street Fighter III 3rd Strike 1518 Atomic Point 18 Street Fighter III 2nd Impact 1519 Puzzle & Action:Tant-R (Korea) 19 Street Fighter III : New Generation 1520 Puzzle & Action 2 Ichidant-R (En) 20 Marvel Super Heroes 1521 Puzzle & Action 2 Ichidant-R (Kor) 21 Marvel Super Heroes Vs. St Fighter 1522 The Newzealand Story 22 Marvel Vs. Capcom : Super Heroes 1523 Puzzle Bobble 23 X-Men : Children oF the Atom 1524 Puzzle Bobble 2 24 X-Men Vs. Street Fighter 1525 Puzzle Bobble 3 25 Hyper Street Fighter II : AE 1526 Puzzle Bobble 4 26 Super Street Fighter II : New C 1527 Bust-A-Move Again 27 Super Street Fighter II Turbo 1528 Puzzle De Pon! 28 Super Street Fighter II X : GMC 1529 Dolmen 29 Street Fighter II : The World Warrior 1530 Magical Drop II 30 Street -

Nintendo Game Boy

Nintendo Game Boy Last Updated on September 26, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 4 in 1: #1 Sachen 4-in-1 Fun Pak Interplay Productions 4-in-1 Funpak: Volume II Interplay Productions Addams Family, The Ocean Addams Family, The: Pugsley's Scavenger Hunt Ocean Adventure Island II: Aliens in Paradise, Hudson's Hudson Soft Adventure Island II: Aliens in Paradise, Hudson's: Electro Brain Rerelease Electro Brain Adventure Island, Hudson's Hudson Soft Adventure Island, Hudson's: Electro Brain Rerelease Electro Brain Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle and Friends, The THQ Adventures of Star Saver, The Taito Aerostar VIC Tokai Aerostar: Sunsoft Rerelease Sunsoft Aladdin, Disney's Virgin Interactive Aladdin, Disney's: THQ Rerelease THQ Alfred Chicken Mindscape Alien vs Predator: The Last of His Clan Activision Alien³ LJN All-Star Baseball '99 Acclaim Alleyway Nintendo Altered Space Sony Imagesoft Amazing Penguin Natsume Amazing Spider-Man 3, The: Invasion of the Spider-Slayers LJN Amazing Spider-Man, The LJN Amazing Tater Atlus Animaniacs Konami Arcade Classic #1: Asteroids & Missile Command Nintendo Arcade Classic #2: Centipede & Millipede Nintendo Arcade Classic No. 3: Galaga & Galaxian Nintendo Arcade Classic No. 4: Defender / Joust Nintendo Asteroids Accolade Atomic Punk Hudson Soft Attack of the Killer Tomatoes THQ Avenging Spirit Jaleco Balloon Kid Nintendo Barbie Game Girl Hi-Tech Express Bart Simpson's Escape From Camp Deadly Acclaim Baseball Nintendo Bases Loaded Jaleco Batman Sunsoft Batman Forever Acclaim Batman: Return of the -

5794 Games.Numbers

Table 1 Nintendo Super Nintendo Sega Genesis/ Master System Entertainment Sega 32X (33 Sega SG-1000 (68 Entertainment TurboGrafx-16/PC MAME Arcade (2959 Games) Mega Drive (782 (281 Games) System/NES (791 Games) Games) System/SNES (786 Engine (94 Games) Games) Games) Games) After Burner Ace of Aces 3 Ninjas Kick Back 10-Yard Fight (USA, Complete ~ After 2020 Super 005 1942 1942 Bank Panic (Japan) Aero Blasters (USA) (Europe) (USA) Europe) Burner (Japan, Baseball (USA) USA) Action Fighter Amazing Spider- Black Onyx, The 3 Ninjas Kick Back 1000 Miglia: Great 10-Yard Fight (USA, Europe) 6-Pak (USA) 1942 (Japan, USA) Man, The - Web of Air Zonk (USA) 1 on 1 Government (Japan) (USA) 1000 Miles Rally (World, set 1) (v1.2) Fire (USA) 1941: Counter 1943 Kai: Midway Addams Family, 688 Attack Sub 1943 - The Battle of 7th Saga, The 18 Holes Pro Golf BC Racers (USA) Bomb Jack (Japan) Alien Crush (USA) Attack Kaisen The (Europe) (USA, Europe) Midway (USA) (USA) 90 Minutes - 1943: The Battle of 1944: The Loop 3 Ninjas Kick Back 3-D WorldRunner Borderline (Japan, 1943mii Aerial Assault (USA) Blackthorne (USA) European Prime Ballistix (USA) Midway Master (USA) (USA) Europe) Goal (Europe) 19XX: The War Brutal Unleashed - 2 On 2 Open Ice A.S.P. - Air Strike 1945k III Against Destiny After Burner (World) 6-Pak (USA) 720 Degrees (USA) Above the Claw Castle, The (Japan) Battle Royale (USA) Challenge Patrol (USA) (USA 951207) (USA) Chaotix ~ 688 Attack Sub Chack'n Pop Aaahh!!! Real Blazing Lazers 3 Count Bout / Fire 39 in 1 MAME Air Rescue (Europe) 8 Eyes (USA) Knuckles' Chaotix 2020 Super Baseball (USA, Europe) (Japan) Monsters (USA) (USA) Suplex bootleg (Japan, USA) Abadox - The Cyber Brawl ~ AAAHH!!! Real Champion Baseball ABC Monday Night 3ds 4 En Raya 4 Fun in 1 Aladdin (Europe) Deadly Inner War Cosmic Carnage Bloody Wolf (USA) Monsters (USA) (Japan) Football (USA) (USA) (Japan, USA) 64th. -

List of Game Boy Games

List of Game Boy Games 1) 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 26) America Oudan Ultra Quiz Part 4 Choume Obake Panic!! 27) Amida 2) 4-in-1 Fun Pak 28) Animal Breeder 3) 4-in-1 Fun Pak Volume II 29) Animal Breeder 2 4) A-mazing Tater 30) Animaniacs 5) Aa Harimanada 31) Arcade Classic No. 1: Asteroids & Missile 6) Adventure Island Command 7) Adventure Island II: Aliens in Paradise 32) Arcade Classic No. 2: Centipede & Millipede 8) Adventures of Lolo 33) Arcade Classic No. 3: Galaga & Galaxian 9) Aerostar 34) Arcade Classic No. 4: Defender & Joust 10) After Burst 35) Aretha 11) Agro Soar 36) Aretha II 12) Akazukin Chacha 37) Asterix 13) Akumajou Dracula: Shikkoku Taru Zensoukyoku: Dark Night Prelude 38) Asterix & Obelix 14) Akumajou Special: Boku Dracula-kun 39) Asteroids 15) Aladdin 40) Astro Rabby 16) Alfred Chicken 41) Atomic Punk 17) Alien 3 42) Attack of the Killer Tomatoes 18) Alien Olympics 43) Avenging Spirit 19) Alien vs Predator: The Last of His Clan 44) B.C. Kid 20) All-Star Baseball 99 45) B.C. Kid 2 21) Alleyway 46) Baby T-Rex 22) Altered Space: A 3-D Alien Adventure 47) Balloon Kid 23) Amazing Penguin 48) Bamse 24) America Oudan Ultra Quiz 49) Banishing Racer 25) America Oudan Ultra Quiz Part 2 50) Barbie: Game Girl 51) Bart Simpson's Escape from Camp Deadly 79) Bionic Battler 52) Baseball 80) Bionic Commando 53) Baseball Kids 81) Bishoujo Senshi Sailor Moon 54) Bases Loaded 82) Black Bass: Lure Fishing 55) Batman Forever 83) Blades of Steel 56) Batman: Return of the Joker 84) Blaster Master Boy 57) Batman: The Animated Series 85) Blaster Master Jr.