Illinoisclassica121987damen.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Girls, Girls, Girls the Prostitute in Roman New Comedy and the Pro

Xavier University Exhibit Honors Bachelor of Arts Undergraduate 2016-4 Girls, Girls, Girls The rP ostitute in Roman New Comedy and the Pro Caelio Nicholas R. Jannazo Xavier University, Cincinnati, OH Follow this and additional works at: http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/hab Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Ancient Philosophy Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, and the Other Classics Commons Recommended Citation Jannazo, Nicholas R., "Girls, Girls, Girls The rP ostitute in Roman New Comedy and the Pro Caelio" (2016). Honors Bachelor of Arts. Paper 16. http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/hab/16 This Capstone/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Bachelor of Arts by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Xavier University Girls, Girls, Girls The Prostitute in Roman New Comedy and the Pro Caelio Nick Jannazo CLAS 399-01H Dr. Hogue Jannazo 0 Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................2 Chapter 1: The meretrix in Plautus ..................................................................................................7 Chapter 2: The meretrix in Terence ...............................................................................................15 Chapter 3: Context of Pro Caelio -

Adulescensasvirgo a Note on Terence's Eunuch 908

ADULESCENSASVIRGO A NOTE ON TERENCE'S EUNUCH 908 Z M Packman (University of Natal, Pietermaritzburg) Terence's Eunuchus has been the object of intensive study in a number of recent publications, among them: Stavros A Frangoulidis, "Performance and improvisation in Terence's Eunuchus" (1994); Louise Pearson Smith, "Audience response to rape: Chaerea in Terence's Eunuchus" (1994); Katerina Philippides, "Terence's Eunuchus: Elements of the marriage ritual in the rape scene" (1995); and Cynthia S Dessen, "The figure of the eunuch in Terence's Eunuchus" (1995). The purpose of this note is to call attention to the extraordinary case of the application of a female character designation, virgo, to a male character, an adulescens, in this drama, and to the context in which this application occurs; and to suggest that this linguistic event is relevant to arguments advanced in several of these recent publications. The line in question is Eunuchus 908, and the story context, briefly, is this: A young man, Chaerea, has followed a young girl who caught his notice, and found that she's entered the household of a courtesan, Thais, to whom she'd been given as a gift by an admirer. Chaerea has gained admission to the same household by impersonating a eunuch, a gift from another admirer. His rape of the young girl inside the house is reported by him to a friend, and discovered by Thais and her maid Pythias, after his departure from her house. Chaerea meets Thais and Pythias in the street, still in eunuch's clothes for want of a place to change out of them, and reveals his true identity to them while they reveal to him the true identity of the girl he has attacked, now proven to be a marriageable young woman of citizenship status. -

Terence's Plays

chapter 2 Terence’s Plays: Commentary and Illustration from Manuscript to Print 2.1 Terence as an Educational Classic: Text and Commentary from Antiquity to Medieval and Renaissance Europe Publius Terentius Afer, or Terence, was the author of six plays which premiered in Rome between 166 and 160 bc— Andria, Heauton timorumenos, Eunuchus, Phormio, Hecyra, and Adelphoe. Some information on the circumstances of the production of each play can be obtained from the didascaliae,1 while the prologues reveal that they were produced in a vibrant and at times vitriolic literary environment. A biographical tradition concerning Terence only devel- oped much later; in the early second century ad Suetonius wrote a Life, which was subsequently supplemented and attached to the commentary of Aelius Donatus (for which see below), while in Late Antiquity it appears that another very brief Life, known as the Vita Ambrosiana, was composed, which provides a few facts independent of the Life found in Donatus.2 In these traditions, we are told that Terence came originally from Carthage in Northern Africa (hence his cognomen, Afer, or ‘the African’); that he was taken to Rome at a young age as a slave, and was adopted and freed there by a senator, Terentius Lucanus, from whom he took his name, and by whom he was educated; that he subsequently was befriended by some of the leading figures in Roman society associated with Scipio Africanus Aemilianus (185/ 4– 129 bc); and that he died young on a trip to Greece, where he had gone in order to purchase more comedies to translate. -

Rhetorical and Dramatic Performance in Donatus' Commentary On

chapter 10 From the Stage to the Court: Rhetorical and Dramatic Performance in Donatus’ Commentary on Terence Beatrice da Vela Aelius Donatus’ Commentary on Terence (4th cent. ad) is the most complete late antique exegesis of Terence’s plays, commenting on five of them (Andria, Eunuchus, Adelphoe, Hecyra, Phormio) in full.1 Scholars have often used this work to shed light on Terence’s words and lines which are not sufficiently clear, or to reconstruct extra-textual features (particularly concerning delivery and performance). Besides commenting on Terence’s language and explain- ing the meaning of obscure references in the text (in a way which is very similar to another great late-antique commentary, that of Servius on Vergil), Aelius Donatus is particularly interested in performative elements, especially the different uses of the voice and the gestures of different parts of the body (primarily hands and face).2 The grammarian is able to describe extra-textual features of Terence’s text in detail, showing awareness of and sensibility to the peculiarity of drama as a genre.3 What remains to be determined is the 1 From now on, texts from the Donatus’ Commentary on Terence will be indicated by the abbre- viation Don., followed by the abbreviation for the name of Terence’s play (e.g. Don. Ad. shall be interpreted as Donatus’ commentary on Terence’s Adelphoe). To avoid ambiguity, each time Terence’s text is quoted, the abbreviation of the play is preceded by the abbreviation of the author (e.g. Ter. Ad.). 2 An example of a note on delivery: Don. -

The Terentian Adaptation of the Heauton Timorumenos of Menander Lawrence Richardson, Jr

The Terentian Adaptation of the Heauton Timorumenos of Menander Lawrence Richardson, Jr ERENCE’S SECOND (or possibly third) comedy, the Heauton timorumenos, is the least studied of his plays.1 It is T the only one for which the commentary of Donatus does not survive, and the fragments of Menander’s play of the same name, of which it is presumed to be largely a translation, are too few and scrappy to give us any opportunity to examine how his version may have differed from Terence’s. Scholarly interest has focussed principally on the prologue and especially on the sixth line of this, which is corrupt and unmetrical in the codex Bembinus, our oldest and best manuscript, but is generally agreed to have originally described the play about to be pre- sented as duplex quae ex argumento facta est simplici. The question is: what is this doubling? The obvious answer would seem to be that it is the addition of plot elements taken from another Greek original, the contaminatio that Terence a few lines later admits is his common practice and defends by asserting that in this he is only following the example set by excellent poets: 1 An excellent bibliography for this play is provided by Eckard Lefèvre, Terenz’ und Menanders Heautontimorumenos (Munich 1994) 191–199. To this may be added the following: O. Knorr, “The Character of Bacchis in Terence’s Heautontimorumenos,” AJP 116 (1995) 221–235; J. C. B. Lowe, “The Intrigue of Terence’s Heauton timorumenos,” RhM 141 (1998) 163–171; B. Victor, “Ménandre, Térence et Eckard Lefèvre,” LEC 66 (1998) 53–60; B. -

EJC Cover Page

Early Journal Content on JSTOR, Free to Anyone in the World This article is one of nearly 500,000 scholarly works digitized and made freely available to everyone in the world by JSTOR. Known as the Early Journal Content, this set of works include research articles, news, letters, and other writings published in more than 200 of the oldest leading academic journals. The works date from the mid-seventeenth to the early twentieth centuries. We encourage people to read and share the Early Journal Content openly and to tell others that this resource exists. People may post this content online or redistribute in any way for non-commercial purposes. Read more about Early Journal Content at http://about.jstor.org/participate-jstor/individuals/early- journal-content. JSTOR is a digital library of academic journals, books, and primary source objects. JSTOR helps people discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content through a powerful research and teaching platform, and preserves this content for future generations. JSTOR is part of ITHAKA, a not-for-profit organization that also includes Ithaka S+R and Portico. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. VOLUMEXLI APRIL, 1915 NUMBER 2 STUDIES IN PHILOLOGY A QUARTERLY JOURNAL PUBLISHED UNDER THE DIRECTON OF THE PHILOLOGICALCLUB OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA THE CHARACTERSOF TERENCE By G. KENNETH G. HENRY, PH.D. (Assistant Professorof Latin in the University of North Carolina) CHAPEL HLL PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY THE CHARACTERS OF TERENCE The following paper embodies some of the chief results of an investigation of the characters that appear in the six plays of Terence. -

WOMEN, METAPOETRY, and COMIC RECEPTION in TERENCE a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell Univ

WOMEN, METAPOETRY, AND COMIC RECEPTION IN TERENCE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Goran Vidović February 2016 © 2016 Goran Vidović WOMEN, METAPOETRY, AND COMIC RECEPTION IN TERENCE Goran Vidović, Ph.D. Cornell University 2016 The focus of this study is self-reflexivity as a key to understanding Terence’s dramaturgy and the poetics professed in his prologues. Building upon recent scholarship, I approach Terence’s prologues not as biographical accounts but as fictional compositions with programmatic function. I explore the parallels between the prologues and the plots of his plays, interpreting the plots as metapoetic commentaries on playwriting as described in the prologues. Specifically, I argue that female characters in Terence’s Eunuchus (Chapters 2-5) and Self-Tormentor (6-7) are metaphors for the plays and vice versa. Pursuing the analogy of women and poetry is rewarding for several reasons. The position of women and control over them are of fundamental importance in Menander and Roman comedy. Woman as a metapoetic trope, abundantly attested in ancient literature, especially comedy, highlights the commodification of texts and articulates the poets’ anxiety of ownership and availability of their work. The same concern emerges from Terence’s prologues, mapping onto the themes of sexual exclusivity and anxiety about emotional reciprocity in the plays. Central to Terence’s program is self-positioning vis-à-vis other poets. I first consider a possibly unique case of the woman-as-play trope in Plautus’ (most likely) last play, the Casina, proposing that he playfully commodified his “swan’s song” by imagining its revival (Chapter 1). -

Character Development in Terence's Eunuchus Samantha Davis

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Foreign Languages & Literatures ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 6-9-2016 Mixing the Roman miles: Character Development in Terence's Eunuchus Samantha Davis Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/fll_etds Recommended Citation Davis, Samantha. "Mixing the Roman miles: Character Development in Terence's Eunuchus." (2016). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/fll_etds/31 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Foreign Languages & Literatures ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Candidate Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: , Chairperson by THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico iii Acknowledgements I would like to express the deepest appreciation to my committee chair Professor Osman Umurhan, through whose genius, dedication, and endurance this thesis was made possible. Thank you, particularly, for your unceasing support, ever-inspiring words, and relentless ability to find humor in just about any situation. You have inspired me to be a better scholar, teacher, and colleague. I would also like to extend the sincerest thanks to my excellent committee members, the very chic Professor Monica S. Cyrino and the brilliant Professor Lorenzo F. Garcia Jr., whose editorial thoroughness, helpful suggestions, and constructive criticisms were absolutely invaluable. In addition, a thank you to Professor Luke Gorton, whose remarkable knowledge of classical linguistics has encouraged me to think about language and syntax in a much more meaningful way. -

Menander's Sikyonioi

Gendered Differences in the Recognition Plot: Menander’s Sikyonioi SERENA S. WITZKE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign [email protected] Introduction Since its rediscovery in 1901, with additional fragments found and then published in the 1960s1, Sikyonioi has intrigued New Comedy scholars2. Despite frustrating lacunae, the plot of this double recognition comedy has been painstakingly pieced together: a young woman (kidnap- ped at an early age) finds her father, while a mercenary soldier also dis- covers his natal family and new role as an Athenian citizen; they marry3. This widely accepted reconstruction has prompted questions about the way Menander develops his recognition plot; the implications of gender in his identity plays; and the use of the surface-level recognition plot to symbolize internal character development. 1 — See Gomme and Sandbach (1973: 632) and Arnott (2000: 193-195) on discovery of the Sikyonioi manuscripts and Handley (2011) and Blanchard (2014) on the rediscovery of Menander in general. 2 — On title Sikyonioi vs. Sikionios, see Arnott (1997a: 1-3; 2000: 196-97), Gomme and Sandbach (1973: 632-33), and R. Kassel (1965). I follow Arnott in the use of Sikyonioi. 3 — Arnott (1997abc, 2000); Belardinelli (1994); Blanchard & Bataille (1965); Gomme & Sandbach (1973); Handley (1965); Kassel (1965); Lloyd-Jones (1966); Merkelbach (1966). EuGeStA - n°6 - 2016 42 SERENA S. WITZKE I argue here that the design of the plot of Sikyonioi reveals the gen- dering of anagnorisis through the play’s unique man-woman double recognition. Menander’s surface-level recognitions (the literal discovery of natal identity) are symbolic of the inner development of the recognized characters4, but I suggest that while the recognition plot allows men to discover natal identity and pushes them toward character development, the recognition of a woman puts an end to her dramatic journey imme- diately. -

Girls and Trauma in New Comedy

Girls and Trauma in New Comedy The plots, generic rules and stage humor of New Comedy both require and mask a good deal of personal trauma, much of it experienced by girls. Sources of trauma include, for citizen women, long-term displacement from family, fear of permanent separation and loss of citizenship, prospect of enforced concubinage to unpleasant soldiers, sexual enslavement, physical abuse, male threats and violence, and, finally, rape. Displaced daughters brought up in brothels fear sexual abuse and trafficking. Displacement from families occurs in infancy or early childhood and forces citizen girls into dangerous situations. Domestic violence is represented, as well. Although New Comedy focuses on citizen families, it stages many non-citizen women, chiefly slaves and meretrices, who also experience trauma. Ancillae regularly suffer torture and abuse, from a young age. The meretrices most at risk are typically about sixteen years old. On the page, these traumas are easy to miss, but in performance they would be unmistakable: the famous canticum of Ballio in Pseudolus threatens appalling tortures for his meretrices, who would be staged as terrified. The specter of sexual trafficking haunts the lives of enslaved meretrices: see, for example, the soldiers planning to take away Planesium of Curculio and Phoenicium of Pseudolus. Indeed, the propensity of soldiers toward physical violence is widely staged, from Menander’s Perikeiromene to Plautus’ Truculentus and Poenulus, to Terence’s Eunuchus, among others. Forcible physical removal is a further threat for meretrices both free and unfree, permanent and temporary (i.e., the pseudo-meretrix): Pyrgopolinices kidnaps Pasicompsa, much against her will, in Miles Gloriosus, and in Adelphoe Aeschines abducts a psaltria from her pimp, for his infatuated brother; because she does not seem to speak the local language (Marshall 2013), she is terrified and weeping, having no idea who he is or what is happening. -

Terence Masterproef

Word Order of Demonstrative Pronouns in Terence’s Comedies Kris Wayenberg Universiteit Gent, master taal- en letterkunde, twee talen: Latijn en Engels Masterproef academiejaar 2010-2011 Promotor: Wolfgang de Melo Table of contents: 1. General introduction.............................................................................................................. p. 3 2. Introduction to Roman comedy.............................................................................................. p. 4 2.1. Greek origins..................................................................................................................... p. 4 2.2. Language........................................................................................................................... p. 5 2.3. Metrical features................................................................................................................ p. 6 3. Introduction on Terence......................................................................................................... p. 6 3.1. Terence’s life..................................................................................................................... p. 6 3.2. Terence’s comedies........................................................................................................... p. 7 3.2.1. Andria ..................................................................................................................... p. 8 3.2.2. Hecyra .................................................................................................................... -

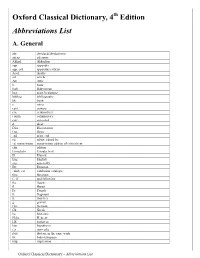

Abbreviations List A

Oxford Classical Dictionary, 4th Edition Abbreviations List A. General abr. abridged/abridgement adesp. adespota Akkad. Akkadian app. appendix app. crit. apparatus criticus Aeol. Aeolic art. article Att. Attic b. born Bab. Babylonian beg. at/nr. beginning bibliog. bibliography bk. book c. circa cent. century cm. centimetre/s comm. commentary corr. corrected d. died Diss. Dissertation Dor. Doric end at/nr. end ed. editor, edited by ed. maior/minor major/minor edition of critical text edn. edition Einzelschr. Einzelschrift El. Elamite Eng. English esp. especially Etr. Etruscan exhib. cat. exhibition catalogue fem. feminine f., ff. and following fig. figure fl. floruit Fr. French fr. fragment ft. foot/feet g. gram/s Ger. German Gk. Greek ha. hectare/s Hebr. Hebrew HS sesterces hyp. hypothesis i.a. inter alia ibid. ibidem, in the same work IE Indo-European imp. impression Oxford Classical Dictionary – Abbreviations List in. inch/es introd. introduction Ion. Ionic It. Italian kg. kilogram/s km. kilometre/s lb. pound/s l., ll. line, lines lit. literally lt. litre/s L. Linnaeus Lat. Latin m. metre/s masc. masculine mi. mile/s ml. millilitre/s mod. modern MS(S) manuscript(s) Mt. Mount n., nn. note, notes n.d. no date neut. neuter no. number ns new series NT New Testament OE Old English Ol. Olympiad ON Old Norse OP Old Persian orig. original (e.g. Ger./Fr. orig. [edn.]) OT Old Testament oz. ounce/s p.a. per annum PIE Proto-Indo-European pl. plate plur. plural pref. preface Proc. Proceedings prol. prologue ps.- pseudo- Pt. part ref. reference repr.