Of 21 Before the US COPYRIGHT OFFICE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

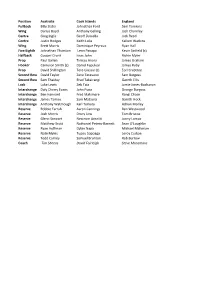

Position Australia Cook Islands England Fullback Billy Slater

Position Australia Cook Islands England Fullback Billy Slater Johnathan Ford Sam Tomkins Wing Darius Boyd Anthony Gelling Josh Charnley Centre Greg Inglis Geoff Daniella Jack Reed Centre Justin Hodges Keith Lulia Kallum Watkins Wing Brett Morris Dominique Peyroux Ryan Hall Five Eighth Johnathan Thurston Leon Panapa Kevin Sinfield (c) Halfback Cooper Cronk Issac John Richie Myler Prop Paul Gallen Tinirau Arona James Graham Hooker Cameron Smith (c) Daniel Fepuleai James Roby Prop David Shillington Tere Glassie (c) Eorl Crabtree Second Row David Taylor Zane Tetevano Sam Burgess Second Row Sam Thaiday Brad Takairangi Gareth Ellis Lock Luke Lewis Zeb Taia Jamie Jones-Buchanan Interchange Daly Cherry Evans John Puna George Burgess Interchange Ben Hannant Fred Makimare Rangi Chase Interchange James Tamou Sam Mataora Gareth Hock Interchange Anthony Watmough Karl Temata Adrian Morley Reserve Robbie Farrah Aaron Cannings Ben Westwood Reserve Josh Morris Drury Low Tom Briscoe Reserve Glenn Stewart Neccrom Areaiiti Jonny Lomax Reserve Matthew Scott Nathaniel Peteru-Barnett Sean O'Loughlin Reserve Ryan Hoffman Dylan Napa Michael Mcllorum Reserve Nate Myles Tupou Sopoaga Leroy Cudjoe Reserve Todd Carney Samuel Brunton Rob Burrow Coach Tim Sheens David Fairleigh Steve Mcnamara Fiji France Ireland Italy Jarryd Hayne Tony Gigot Greg McNally James Tedesco Lote Tuqiri Cyril Stacul John O’Donnell Anthony Minichello (c) Daryl Millard Clement Soubeyras Stuart Littler Dom Brunetta Wes Naiqama (c) Mathias Pala Joshua Toole Christophe Calegari Sisa Waqa Vincent -

Rush Three of Them Decided to - Geddy Recieved a Phone Reform Rush but Without Call from Alex

history portraits J , • • • discography •M!.. ..45 I geddylee J bliss,s nth.slzers. vDcals neil pearl: percussion • alex liFesDn guitars. synt.hesizers plcs: Relay Photos Ltd (8); Mark Weiss (2); Tom Farrington (1): Georg Chin (1) called Gary Lee, generally the rhythm 'n' blues known as 'Geddy' be combo Ogilvie, who cause of his Polish/Jewish shortly afterwards also roots, and a bassist rarely changed their me to seen playing anything JUdd, splitting up in Sep other than a Yardbirds bass tember of the sa'l1le year. line. John and Alex, w. 0 were In September of the same in Hadrian, contacted year The Projection had Geddy again, and the renamed themselves Rush three of them decided to - Geddy recieved a phone reform Rush but without call from Alex. who was in Lindy Young, who had deep trouble. Jeff Jones started his niversity was nowhere to be found, course by then. In Autumn although a gig was 1969 the first Led Zeppelin planned for that evening. LP was released, and it hit Because the band badly Alex, Geddy an(i John like needed the money, Geddy a hammer. Rush shut them helped them out, not just selves away in their rehe providing his amp, but also arsal rooms, tUfned up the jumping in at short notice amp and discovered the to play bass and sing. He fascination of heavy was familiar with the Rush metaL. set alreadY, as they only The following months played well-known cover were going toJprove tough versions, and with his high for the three fYoung musi voice reminiscent of Ro cians who were either still bert Plant, he comple at school or at work. -

TO: NZRL Staff, Districts and Affiliates and Board FROM: Cushla Dawson

TO: NZRL Staff, Districts and Affiliates and Board FROM: Cushla Dawson DATE: 28 October 2008 RE: Media Summary Wednesday 29 October to Monday 03 November 2008 Slater takes place among the greats: AUSTRALIA 52 ENGLAND 4. Billy Slater last night elevated himself into the pantheon of great Australian fullbacks with a blistering attacking performance that left his coach and Kangaroos legend Ricky Stuart grasping for adjectives. Along with Storm teammate and fellow three-try hero Greg Inglis, Slater turned on a once-in-a-season performance to shred England to pieces and leave any challenge to Australia's superiority in tatters. It also came just six days after the birth of his first child, a baby girl named Tyla Rose. Kiwis angry at grapple tackle: The Kiwis are fuming a dangerous grapple tackle on wing Sam Perrett went unpunished in last night's World Cup rugby league match but say they won't take the issue further. Wing Sam Perrett was left lying motionless after the second tackle of the match at Skilled Park, thanks to giant Papua New Guinea prop Makali Aizue. Replays clearly showed Aizue, the Kumuls' cult hero who plays for English club Hull KR, wrapping his arm around Perrett's neck and twisting it. Kiwis flog Kumuls: New Zealand 48 Papua New Guinea NG 6. A possible hamstring injury to Kiwis dynamo Benji Marshall threatened to overshadow his side's big win over Papua New Guinea at Skilled Park last night. Arguably the last superstar left in Stephen Kearney's squad, in the absence of show-stoppers like Roy Asotasi, Frank Pritchard and Sonny Bill Williams, Marshall is widely considered the Kiwis' great white hope. -

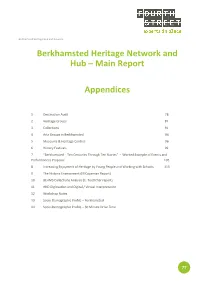

Berkhamsted Heritage Network and Hub – Main Report Appendices

Berkhamsted Heritage Hub and Network Berkhamsted Heritage Network and Hub – Main Report Appendices 1 Destination Audit 78 2 Heritage Groups 87 3 Collections 91 4 Arts Groups in Berkhamsted 94 5 Museums & Heritage Centres 96 6 History Festivals 99 7 “Berkhamsted - Ten Centuries Through Ten Stories” - Worked Example of Events and Performances Proposal 105 8 Increasing Enjoyment of Heritage by Young People and Working with Schools 113 9 The Historic Environment (M Copeman Report) 10 BLHMS Collections Analysis (E. Toettcher report) 11 HKD Digitisation and Digital / Virtual Interpretation 12 Workshop Notes 13 Socio-Demographic Profile – Berkhamsted 14 Socio-Demographic Profile – 30 Minute Drive Time 77 Berkhamsted Heritage Hub and Network 1 Destination Audit 1.1 Access The A4251 runs through the centre of Berkhamsted. It connects to the A41, which runs adjacent to the town. The A41 connects in the east to the M1 and M25. Figure 48: Distance & Drive Time to large towns & cities Name Distance (mi.) Drive Time (mins) Tring 6.7 13 Hemel Hempstead 7.4 15 Watford 12.6 25 Aylesbury 13.8 22 Leighton Buzzard 14.3 31 High Wycombe 15.2 35 Luton 18.2 32 Source: RAC Route Planner There are currently 1,030 parking places around the town. Most are charged. Almost half are at the station, most of which are likely to be used by commuters on weekdays but available for events at weekends. A new multi-storey will open in 2019 to alleviate parking pressures. This is central to the town, next to Waitrose, easy to find, and so it will a good place to locate heritage information. -

New England Patriots Vs . New Orleans Saints

NEW EN GLA N D PATRIOTS VS . NEW ORLEA N S SAI N TS # NAME ................ POS Thursday, August 12, 2010 • 7:30 p.m. • Gillette Stadium # NAME ................ POS 3 Stephen Gostkowski .........K 4 Sean Canfield ................. QB 7 Zac Robinson ................ QB 5 Garrett Hartley...................K 8 Brian Hoyer .................. QB PATRIOTS OFFENSE PATRIOTS DEFENSE 6 Thomas Morstead ..............P 10 Darnell Jenkins ............WR 9 Drew Brees .................... QB 11 Julian Edelman ..............WR LE: 94 Ty Warren 91 Myron Pryor 96 Jermaine Cunningham WR: 83 Wes Welker 19 Brandon Tate 88 Sam Aiken 10 Chase Daniel .................. QB 90 Darryl Richard 12 Tom Brady .................... QB 18 Matthew Slater 17 Taylor Price 15 Rod Owens 11 Patrick Ramsey ............... QB NT: 75 Vince Wilfork 97 Ron Brace 74 Kyle Love 14 Zoltan Mesko ...................P LT: 72 Matt Light 76 Sebastian Vollmer 66 George Bussey 12 Marques Colston ............ WR 15 Rod Owens ...................WR 13 Rod Harper .................... WR RE: 99 Mike Wright 68 Gerard Warren 92 Damione Lewis 17 Taylor Price ...................WR LG: 70 Logan Mankins* 63 Dan Connolly 71 Eric Ghiaciuc 14 Andy Tanner .................. WR 18 Matthew Slater ..............WR 71 Brandon Deaderick 66 Kade Weston OLB: 95 Tully Banta-Cain 58 Pierre Woods 93 Marques Murrell 15 Courtney Roby ............... WR 19 Brandon Tate ................WR C: 67 Dan Koppen 63 Dan Connolly 69 Ryan Wendell 16 Lance Moore .................. WR 21 Fred Taylor ....................RB ILB: 51 Jerod Mayo 52 Eric Alexander 44 Tyrone McKenzie 17 Robert Meachem ............ WR RG: 61 Stephen Neal 60 Rich Ohrnberger 62 Ted Larsen 22 Terrence Wheatley .........CB 18 Larry Beavers ................ WR 65 Darnell Stapleton 23 Leigh Bodden .................CB ILB: 59 Gary Guyton 55 Brandon Spikes 48 Thomas Williams 19 Devery Henderson ........ -

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration REGISTER

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration REGISTER A Daily Summary of Motor Carrier Applications and of Decisions and Notices Issued by the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration DECISIONS AND NOTICES RELEASED January 24, 2020 -- 10:30 AM NOTICE Please note the timeframe required to revoke a motor carrier's operating authority for failing to have sufficient levels of insurance on file is a 33 day process. The process will only allow a carrier to hold operating authority without insurance reflected on our Licensing and Insurance database for up to three (3) days. Revocation decisions will be tied to our enforcement program which will focus on the operations of uninsured carriers. This process will further ensure that the public is adequately protected in case of a motor carrier crash. Accordingly, we are adopting the following procedure for revocation of authority; 1) The first notice will go out three (3) days after FMCSA receives notification from the insurance company that the carrier's policy will be cancelled in 30 days. This notification informs the carrier that it must provide evidence that it is in full compliance with FMCSA's insurance regulations within 30 days. 2) If the carrier has not complied with FMCSA's insurance requirements after 30 days, a final decision revoking the operating authority will be issued. NAME CHANGES NUMBER TITLE DECIDED FF-857 PACIFIC REMOVAL SERVICES, INC. - N HOLLYWOOD, CA 01/21/2020 MC-101312 ARAV TRUCKING INC - MADERA, CA 01/21/2020 MC-1025938 ON THE SPECTRUM TRANSPORT LLC - CORPUS CHRISTI, TX 01/21/2020 MC-1028027 MARISH ON TIME TRANSPORT LLC - ROWLETT, TX 01/21/2020 MC-1047584 B-E-C TRUCKING, LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY - CROSBY, TX 01/21/2020 MC-1047775 LEN JOHNSTONE TRANSPORT LLC - ASH FORK, AZ 01/21/2020 MC-1048978 CARTER TRANSPORTATION LLC - NEWNAN, GA 01/21/2020 MC-1058463 ATA AUTO TRANSPORT, LLC - ST AUGUSTINE, FL 01/21/2020 MC-1064977 TALBOTT'S TRANSPORT INC - DURHAM, NC 01/21/2020 MC-1064977 TALBOTT'S TRANSPORT, INC. -

Skills Tour at PIHC Highlights Rural Healthcare

ShellbrookShellbrook ChronicleChronicle The voice of the Parkland for over 107 years VOL. 107 NO. 39 PMR #40007604 Shellbrook, Saskatchewan Thursday, September 26, 2019 www.shellbrookchronicle.com Skills Tour at PIHC highlights rural healthcare In the afternoon, students taking part in the Rural Skills Tour stopped by the car show and book launch being hosted by Parkland Integrated Health Centre’s long-term care residents. Community engagement was a key piece of showing students what rural healthcare has to offer. Students hoping for careers in health- cruit ones – out to rural areas to take during a traumatic code, assist with local recreation and housing, and also care got a taste of all that rural health- the stigma and scariness out of rural crutch walking, practice spirometry (a learned about the benefits of living in a care has to offer on Sept. 21, when staff healthcare, and show what all the ben- test that measures how well a patient’s small town. and volunteers at Parkland Integrated efits are and what life in rural Saskatch- lungs are working), and sharpen their Up next, they went on tour of town, Healthcare Centre (PIHC) opened up ewan actually looks like, living and suturing skills on a banana. and were tasked with filling in a Bingo the facility for a Rural Skills Tour. working,” explained Lynne Farthing, a “Once we had the volunteers in place, card of information about the commu- Hosted in conjunction with Sask- registered nurse at PIHC. and a schedule set up, then it was mat- nity of Shellbrook by stopping in at lo- Docs, the busy day saw 39 post-second- Starting bright and early in the morn- ter of making sure we had all the sup- cal businesses, or chatting with people ary students, and, for the first time ever, ing, the visiting students were eased plies organized for everybody, and on the street. -

Indianapolis Marathon - Half-Marathon - Results Onlineraceresults.Com

Indianapolis Marathon - Half-Marathon - results OnlineRaceResults.com PLACE NAME DIV DIV PL 5MI PACE TIME ----- ---------------------- ------- --------- ----------- ------- ----------- 1 Paul Howarth M 30-34 1/183 26:54 5:26 1:11:05 2 Bryan Phillips M 20-24 1/87 27:40 5:37 1:13:26 3 Jason Gantt M 30-34 2/183 27:31 5:38 1:13:40 4 Andrew Jacobi M 20-24 2/87 28:45 5:49 1:16:03 5 Jayson Meyer M 25-29 1/150 29:12 5:54 1:17:15 6 Parker Jones M 20-24 3/87 30:01 6:05 1:19:38 7 Jonathan Damiano M 20-24 4/87 30:36 6:06 1:19:54 8 Dan Schramm M 45-49 1/164 30:37 6:08 1:20:21 9 Brad Sugarman M 35-39 1/143 30:23 6:11 1:20:53 10 Kevin Monroe M 35-39 2/143 30:32 6:11 1:20:57 11 Jared Anderson M 35-39 3/143 30:54 6:12 1:21:12 12 Alex McPherson M 45-49 2/164 31:02 6:13 1:21:18 13 Donald Barnard M 30-34 3/183 31:08 6:15 1:21:50 14 Daniel Snyder M 20-24 5/87 30:43 6:17 1:22:15 15 Robert Isaacs M 45-49 3/164 31:51 6:17 1:22:16 16 Michael Lautzenheiser M 30-34 4/183 31:19 6:18 1:22:21 17 Isaac Willett M 30-34 5/183 31:41 6:20 1:22:50 18 Andy Ray M 30-34 6/183 31:11 6:20 1:22:52 19 Emily Cochard F 20-24 1/204 32:34 6:26 1:24:08 20 Jacob Englander M 25-29 2/150 31:57 6:27 1:24:21 21 Steven Fetz M 25-29 3/150 32:04 6:27 1:24:21 22 Anne Clinton F 25-29 1/284 31:56 6:28 1:24:36 23 Saad Haq M 35-39 4/143 31:56 6:28 1:24:42 24 Daniel Haynes M 25-29 4/150 32:27 6:29 1:24:44 25 Jay Hawkey M 20-24 6/87 32:55 6:31 1:25:14 26 Patrick Cassidy M 45-49 4/164 31:58 6:31 1:25:18 27 Robert Sommer M 20-24 7/87 31:53 6:32 1:25:27 28 Nikki Domico F 25-29 2/284 32:02 6:33 1:25:41 29 Maxwell Rehlander M 1-19 1/27 32:50 6:33 1:25:45 30 Tim Wiseman M 40-44 1/153 33:11 6:36 1:26:17 31 W. -

PLAYERS in the PROS (Veteran Players That Are on NFL Rosters, As of June 22, 2020)

PLAYERS IN THE PROS (Veteran players that are on NFL rosters, as of June 22, 2020) Chase Litton QB Free Agent Ty Long P Los Angeles Chargers Albert McClellan LB Free Agent Garrett Marino DT Dallas Cowboys C.J. Reavis DB Atlanta Falcons J.J. Nelson WR Free Agent Darryl Roberts CB Detroit Lions Anthony Rush DT Philadelphia Eagles Justin Rohrwasser K New England Patriots Nick Vogel K Baltimore Ravens Lee Smith TE Buffalo Bills Joe Webb QB Free Agent Kaare Vedvik P Buffalo Bills Darious Williams CB Los Angeles Rams MIDDLE TENNESSEE UTEP Chandler Brewer G Los Angeles Rams Will Hernandez OG New York Giants Kevin Byard S Tennessee Titans Aaron Jones RB Green Bay Packers CHARLOTTE Darius Harris LB Kansas City Chiefs Cedrick Lang OT Indianapolis Colts Cameron Clark OL New York Jets Richie James, Jr. WR San Francisco 49ers Nik Needham CB Miami Dolphins Nate Davis OL Tennessee Titans Jovante Moffatt S Cleveland Browns Roy Robertson-Harris DE Chicago Bears Alex Highsmith LB Pittsburgh Steelers Tyshun Render DE Miami Dolphins Kahani Smith S Denver Broncos Benny LeMay RB Cleveland Browns Charvarius Ward CB Dallas Cowboys Eric Tomlinson TE New York Giants Larry Ogunjobi DL Cleveland Browns Nick Usher LB Las Vegas Raiders NORTH TEXAS FIU Nate Brooks CB Miami Dolphins UTSA Ike Brown CB Buffalo Bills Jalen Guyton WR Los Angeles Chargers Eric Banks DL Los Angeles Rams Johnathan Cyprien S Free Agent Kemon Hall CB Minnesota Vikings Marcus Davenport DE New Orleans Saints T.Y. Hilton WR Indianapolis Colts LaDarius Hamilton DE Dallas Cowboys Josh Dunlop G Los Angeles Chargers Anthony Jones RB Seattle Seahawks Jamize Olawale FB Dallas Cowboys David Morgan TE Free Agent Dieugot Joseph OL Free Agent Craig Robertson LB New Orleans Saints Brian Price DT Jacksonville Jaguars Napoleon Maxwell RB Chicago Bears Jeff Wilson, Jr. -

Certain Early Ancestors

CERTAIN EARLY ANCESTORS GENEALOGIES OF THE BUTTERFIELDS OF CHELMSFORD, MASS., OF THE PARKERS OF WOBURN AND CHELMSFORD, MASS., OF THE HOHNS OF ONTARIO, CANADA, OF THE JOHNSONS OF ROXBURY, MASS., AND OF THE HEATHS OF HAVERHILL, MASS. Compiled from records of the First Church of Christ in Frances town, N. H., '1791.(deposited at the State Library, Concord, N. H.), and from framed old family registers, and Bibles, and from the history · of Old Families of Amesbury and Salisbury, Mass., and from town histories of Roxbury, Mass., Ryegate, Vt., Lyndeboro and Francestown, N. H., and from histories of Buf, falo and Erie Co., N. Y., Macomb Co., and Ionia and Montcalm Cos., Mich., and Houston Co., Minn., and from published gene, alogies, gravestone records and censuses, and from personal recoJ, lections of Nellie B. Buffum, Emma C. Perry, Lilly Ellis and Jessie Culver, extended and substantiated by inspection of offi, cial documents of births, marriages, deaths, deeds, probate rec, ords, pension papers and war records in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Vermont, New York, Michigan and Ontario. Compiled by Cora Elizabeth Hahn Smith I 9 4 3 Copyright 1944 Cora Elizabeth Hahn Smith Lithoprinted in U.S.A. EDWARDS BROTHERS, INC. ANN .-4,RROR, MIC~ICAN 1944 FOREWORD This book of early New England and Ontario fam ilies records, in the case of the Butterfields of Chelms ford, Mass., primarily, the descendants of William Butterfield (family #4),beginning with the record of his birth and including his marriage to Rebecca Parker as given in New England Historical and Genealogical Register of January 1890, page 37, and continuing with the historical account of the man as given in History of Francestown, New Hampshire,by Cochrane, published 1895, and including data obtained through corresponding with various de3~endants of his children who had records of their family descent. -

Wmc Investigation: 10-Year Analysis of Gender & Oscar

WMC INVESTIGATION: 10-YEAR ANALYSIS OF GENDER & OSCAR NOMINATIONS womensmediacenter.com @womensmediacntr WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER ABOUT THE WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER In 2005, Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan, and Gloria Steinem founded the Women’s Media Center (WMC), a progressive, nonpartisan, nonproft organization endeav- oring to raise the visibility, viability, and decision-making power of women and girls in media and thereby ensuring that their stories get told and their voices are heard. To reach those necessary goals, we strategically use an array of interconnected channels and platforms to transform not only the media landscape but also a cul- ture in which women’s and girls’ voices, stories, experiences, and images are nei- ther suffciently amplifed nor placed on par with the voices, stories, experiences, and images of men and boys. Our strategic tools include monitoring the media; commissioning and conducting research; and undertaking other special initiatives to spotlight gender and racial bias in news coverage, entertainment flm and television, social media, and other key sectors. Our publications include the book “Unspinning the Spin: The Women’s Media Center Guide to Fair and Accurate Language”; “The Women’s Media Center’s Media Guide to Gender Neutral Coverage of Women Candidates + Politicians”; “The Women’s Media Center Media Guide to Covering Reproductive Issues”; “WMC Media Watch: The Gender Gap in Coverage of Reproductive Issues”; “Writing Rape: How U.S. Media Cover Campus Rape and Sexual Assault”; “WMC Investigation: 10-Year Review of Gender & Emmy Nominations”; and the Women’s Media Center’s annual WMC Status of Women in the U.S. -

BEST PICTURE Director Actor in a Leading Role ACTRESS in A

Up–to–the–minute Oscar news and wrap-up on vulture.com 2011 OSCAR POOL BALLOT BEST PICTURE FOreiGN LANGuaGE FilM DOcuMENtarY Feature Black Swan Biutiful Exit Through the Gift Shop Banksy and Jaimie D’Cruz The Fighter Mexico | Directed by Alejandro González Iñárritu Gasland Josh Fox and Trish Adlesic Inception Dogtooth (Kynodontas) Inside Job Charles Ferguson and Audrey Marrs Greece | Directed by Giorgos Lanthimos The Kids Are All Right Restrepo Tim Hetherington and Sebastian Junger In a Better World (Hævnen) The King’s Speech Waste Land Lucy Walker and Angus Aynsley Denmark | Directed by Susanne Bier 127 Hours Incendies DOcuMENtarY SHOrt SUBJect The Social Network Canada | Directed by Denis Villeneuve Killing in the Name Nominees to be determined Toy Story 3 Outside the Law (Hors-la-loi) Poster Girl Nominees to be determined True Grit Algeria | Directed by Rachid Bouchareb Strangers No More Karen Goodman and Kirk Simon Winter’s Bone OriGINal SCOre Sun Come Up Jennifer Redfearn and Tim Metzger DirectOR How to Train Your Dragon John Powell The Warriors of Qiugang Ruby Yang and Darren Aronofsky Black Swan Inception Hans Zimmer Thomas Lennon David O. Russell The Fighter The King’s Speech Alexandre Desplat ANIMated SHOrt FilM Tom Hooper The King’s Speech 127 Hours A.R. Rahman Day & Night Teddy Newton David Fincher The Social Network The Social Network Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross The Gruffalo Jakob Schuh and Max Lang Joel Coen and Ethan Coen True Grit OriGINal SONG Let’s Pollute Geefwee Boedoe ActOR IN A LeadiNG ROle Country Strong “Coming Home” The Lost Thing Shaun Tan and Andrew Ruhemann Javier Bardem Biutiful Music and Lyric by Tom Douglas, Troy Verges, Madagascar, carnet de voyage (Madagascar, a and Hillary Lindsey Journey Diary) Bastien Dubois Jeff Bridges True Grit Tangled “I See the Light” Jesse Eisenberg The Social Network Music by Alan Menken, Lyric by Glenn Slater LIVE ActiON SHOrt FilM Colin Firth The King’s Speech 127 Hours “If I Rise” The Confession Tanel Toom James Franco 127 Hours Music by A.R.