Design-Based Regulations for Manufactured Urban Infill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inclusionary Trail Planning Toolkit

Inclusionary Trail Planning Toolkit A guide to planning and programming equitable trail networks Funding for this report was provided by the Contents Foreword 1 Section 1: Introduction 2 Inclusionary Planning 2 Equitable Planning 3 Green Gentrification 4 Section 2: Case Studies of Inclusionary Trail Planning 8 Camden, New Jersey 8 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 11 Washington, DC 21 Examples of Successful Programming for Inclusive Trails 23 Section 3: Tools for Planning in Community 27 Community Organizing for Trail Planning 27 Forge Alliances and Building a Base 27 Establishing Buy-in 28 Leadership Development 29 Understanding the Community: Using Data 31 Understanding the Community: Community Mapping 32 Understanding the Community: Employing Social Justice Frameworks 32 Understanding the Community: Is My Community Prone to Gentrification? 33 Planning Events: Origins of Event 36 Planning Events: Outreach for Events 36 Planning Events: Event Logistics 37 Implementation of the Trail: Construction Phase 38 Implementation of the Trail: Celebrate the Opening 39 Implementation of the Trail: Program the Trail 39 Implementation of the Trail: Job Creation 40 Institutional Change 40 Appendix A: Resources for participatory planning events 43 Appendix B: Resources for Data Collection 46 Appendix C: Midwest Academy Racial Justice and Equity Framework 47 Appendix D: Race Forward, Racial Equity Impact Assessments 48 Appendix E: Addressing Gentrification in Communities 50 Appendix F: Training Resources 51 Appendix G: Summary of interviews 53 This report was prepared by Julia Raskin on behalf of the Pennsylvania Environmental Council. Special thanks to the Inclusive Planning Working Group for their expertise, guidance, and time: Shoshanna Akins, Eleanor Horne, Valeria Galarza, Rachel Griffith, and Daniel Paschall. -

East Athens Community Assessment

East Athens Community Assessment Final Report Community Partner East Athens Development Corporation Team Members Leslie Albrycht, Kelli Jo Armstrong, Megan Baer, Meghan Camp, Chelsea Gillus, Nina Goodwin, Emily Hui, Quentara Johnson, Julia Jones, Jennifer Korwan, Nyla Lieu, Lori Skinner, Anna Marie Smith, Kelsey Thompson, Megan Westbrook Instructor Rebecca Matthew, PhD Completed during the Fall of 2014 in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the course SOWK 7153. 12/9/2014 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 4 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Data Collection and Analysis.......................................................................................................... 6 Secondary Data Collection .......................................................................................................... 7 Primary Data Collection .............................................................................................................. 7 Data Analysis .............................................................................................................................. 8 Dissemination of Findings ......................................................................................................... -

Report from the Ad Hoc Committee on Baldwin Hall to the Franklin College Faculty Senate

Report from the Ad Hoc Committee on Baldwin Hall to the Franklin College Faculty Senate Submitted to the Senate for approval, April 17, 2019 Ad Hoc Committee Chair Christopher Pizzino, Associate Professor, Department of English Ad Hoc Committee Members Mary Bedell, Associate Professor, Department of Genetics J. Peter Brosius, Distinguished Research Professor, Department of Anthropology Kristin Kundert, Associate Professor, Department of Theater and Film Studies Michael Usher, Professor, Department of Mathematics “But the past never cooperates by staying in the past. Eventually it always reaches out to us and asks, What have you learned?” Valerie Babb, at public forum Conversation about Slavery at UGA and the Baldwin Site Burials, Richard Russell Special Collections Library, March 25, 2017 (Chronicle of Higher Education, June 23, 2017) 1 CONTENTS I. Introduction: Purpose and Charge of the Ad Hoc Committee 4 A. The discovery and handling of human remains at Baldwin Hall 4 B. Events leading to the formation of the ad hoc committee 7 C. The charge of the ad hoc committee 8 D. Guide to this report: scope, structure, purpose, and use 9 II. Major Faculty Concerns 9 A. Lack of input from archaeologists during the planning of the Baldwin expansion 10 B. Secrecy and lack of community consultation between receipt and announcement of DNA results 12 C. Concerns regarding reburial practice 15 D. Treatment of issues concerning research 18 E. Official responses to valid faculty criticism 23 F. Intimidation and policing of faculty teaching activities 24 G. Institutional culture and its effects on academic freedom and integrity 25 III. Committee Recommendations for Senate Consideration 27 A. -

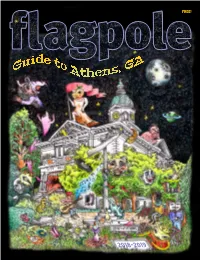

Georgia FOOD • DRINK • ARTS ENTERTAINMENT RECREATION LODGING MAPS

2017–2018 flagpole Guide to ATHENS Georgia FOOD • DRINK • ARTS ENTERTAINMENT RECREATION LODGING MAPS PO AG L L E F M A E G A Z I N SANDWICHES SALADS WRAPS K-BOWLS The Moose Deli�er�!& Cater� �o�. a�ar�-�innin� origina� Wings sandwiches BELGIAN FRIES 10 SIGNATURE SAUCES Sign up for our rewards TRY A KEBA program to earn free food, �pecialt� �res� Burgers OUTDOORSEATING salads and have discounts sent GYRO TODAY! straight to your phone! � SOMETHING EVERYone! 1860 Barnett Shoals Road AS long as everybody likes a good time. Athens • 706.850.7285 Locos is the ultimate place for great food, fun, beverages and catching 1850 Epps Bridge Parkway the game with friends, all in a family friendly environment. With dine Athens • 706.543.8210 in, pick up, delivery or catering, it’s easy to enjoy Locos any time! 1021 Jamestown Blvd. Stop by and see for yourself – Locos has something for everyone. Watkinsville (Drive thru) 706.310.7222 1985 Barnett Shoals Rd. Trivia Tuesdays! 2020 Timothy Rd. Athens, GA 30605 DRINK SPECIALS Athens, GA 30606 306 Exchange Blvd., Suite 200 706.208.0911 Giveaways and Prizes 706.549.7700 Bethlehem • 770.867.4655 dine-in • takeout • delivery • catering LOCOSGRILL.COM KebaGrill.com ƒ 2 201 7–201 8 flagpole Guide to ATHENS flagpole.com TAble OF Contents Athens at a Glance . .4 Stage and Screen . 22. Annual Events . .9 Books and Records . 25. Athens Favorites . 11. Athens Music . 26. Lodging . 12. Food Trucks and Farmers Markets . 29 Art Around Town . 14. Athens and UGA Map . .31 Get Active . -

A Path to Housing Justice in California Facing History, Uprooting Inequality: a Path to Housing Justice in California

Facing History, Uprooting Inequality: A Path to Housing Justice in California Facing History, Uprooting Inequality: A Path to Housing Justice in California Amee Chew with Chione Lucina Muñoz Flegal About This Report This report was produced by PolicyLink with funding from the Melville Charitable Trust. Acknowledgments We are deeply grateful to our community partners who served We thank Michelle Huang at PolicyLink and the USC Equity on the Advisory Committee of this report, for their expertise, Research Institute for data analysis; Heather Tamir at PolicyLink guidance, and insights: for editorial support; Jacob Goolkasian for layout and design; Guadalupe Garcia for logistical support; and Kakuna Kerina for • Alexandra Suh and José Roberto Hernández, Koreatown thorough copyedits. Immigrant Workers Alliance • Anya Lawler and Alexander Harnden, Western Center on We are grateful to the Melville Charitable Trust for supporting Law and Poverty this project. • Ashley Werner, Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability • Camilo Sol Zamora and Cat Kung, Causa Justa :: Just Cause • Christina Livingston, Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment • Cynthia Strathmann, Strategic Actions for a Just Economy • D’Artagnan Scorza and Jelani Hendrix, Uplift Inglewood and Social Justice Learning Institute ©2020 PolicyLink. All rights reserved. • Deborah Thrope and Mariel Block, National Housing Law Project Cover, lower left: In 1963, hundreds of NAACP-CORE members • Jennifer Martinez, PICO California and supporters march in Torrance for fair -

Chronic Urban Trauma and the Slow Violence of Housing Dispossession

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Urban Studies provided by Newcastle University E-Prints Chronic Urban Trauma and the Slow Violence of Housing Dispossession Journal: Urban Studies Manuscript ID CUS-302-18-03.R1 Manuscript Type: Article <b>Discipline: Please select a keyword from the following list Geography that best describes the discipline used in your paper.: World Region: Please select the region(s) that best reflect the focus of your paper. Names of individual countries, Western Europe cities & economic groupings should appear in the title where appropriate.: Major Topic: Please identify up to 5 topics that best identify Class, Community, Displacement/Gentrification, Housing, Inequality the subject of your article.: You may add up to 2 further relevant keywords of your Violence, Trauma choosing below:: http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/cus [email protected] Page 1 of 24 Urban Studies 1 2 3 Chronic Urban Trauma: the Slow Violence of Housing Dispossession 4 5 6 7 8 Abstract 9 This paper sets the idea of slow violence into dialogue with trauma, to understand the practice 10 11 and legitimization of the repeated damage done to certain places through state violence. Slow 12 13 violence (Nixon 2011) describes the ‘attritional lethality’ of many contemporary effects of 14 globalization. While originating in environmental humanities, it has clear relevance for urban 15 16 studies. After assessing accounts of the post-traumatic city, the paper draws insights from 17 feminist psychiatry and postcolonial analysis to develop the concept of chronic urban trauma, 18 19 as a psychological effect of violence involving an ongoing relational dynamic. -

Brooklyn Law Review

BROOKLYN LAW REVIEW Community Benefits Agreements: A Symptom, Not the Antidote, of Bilateral Land Use Regulation Alejandro E. Camacho Vol. 78 Winter 2013 No. 2 Production\Law Reviews\1238 Brooklyn Law School\516575 Brooklyn Law Review 78#2\Working Files\516575 cover.indd Community Benefits Agreements A SYMPTOM, NOT THE ANTIDOTE, OF BILATERAL LAND USE REGULATION∗ Alejandro E. Camacho† INTRODUCTION The Lorenzo is an upscale, Italian-themed apartment and retail complex near the University of Southern California.1 Primarily marketed to USC students and young professionals, the Lorenzo lures prospective tenants with its indoor basketball courts, stadium-seating movie theater, three-story fitness center, climbing wall, and on-site café.2 However, what visitors will not see in this $250 million apartment complex is that the on-site community medical clinic will operate rent-free for the next twenty years.3 Also missing from the list of amenities are the funds that the developer earmarked for job training, local construction workers, and nearby small businesses, as well as the low-income-housing community trust created during the land use negotiation process.4 These unseen features are part of the Community Benefits Agreement (CBA) negotiated between a South Los Angeles community coalition— United Neighbors in Defense Against Displacement ∗ © 2013 Alejandro E. Camacho. All Rights Reserved. † Professor of Law and Director, Center for Land, Environment, and Natural Resources, University of California, Irvine School of Law; Member Scholar, Center for Progressive Reform. I would like to thank Gregg Macey, David Reiss, Chris Serkin, and the Brooklyn Law Review for inviting me to be a part of the David G. -

Community Agenda for the Athens-Clarke County Comprehensive Plan

Community Agenda for the Athens-Clarke County Comprehensive Plan April 9, 2008 Table of Contents I. Community Agenda - Athens-Clarke County 1. Resolution ....................................................................................................1 2. Introduction .................................................................................................2 3. Community Vision Guiding Principles for Community Agenda ..........................................6 Community Character Areas ....................................................................24 Growth Concept / Character Areas Map.................................................32 Implementation: Future Development Map’s Implementation Strategies.........................................................................33 Implementation: Future Development Map..........................................44 Implementation: Zoning Compatibility Matrix.....................................45 4. Vision Statements, Issues and Opportunities & Policies.......................46 5. Short Term Work Plan................................................................................71 6. Appendix Report of Accomplishments ......................................................................82 Capital Budget and Improvement Plan...................................................105 Athens-Clarke County Community Agenda Page 1 of 249 Introduction Athens-Clarke County Community Agenda Page 2 of 249 Introduction The Comprehensive Plan for Athens-Clarke County and the City of Winterville, -

Is It Possible to Plan Displacement-Free Urban Renewal? a Comparative Analysis of the National Urban Renewal Program in Turkey

IS IT POSSIBLE TO PLAN DISPLACEMENT-FREE URBAN RENEWAL? A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE NATIONAL URBAN RENEWAL PROGRAM IN TURKEY BY DENIZ AY DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Regional Planning in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2016 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Geoffrey J. Hewings, Chair Professor Rob Olshansky, Director of Research Professor Asef Bayat Assistant Professor Andrew Greenlee ABSTRACT This is a study of development-induced displacement in the urban context. It explores the planning environment that shapes the ostensibly well-intentioned development projects that often displace existing residents from their established living spaces. This study frames development- induced displacement as a “paradox of public interest” because displacing some members of the public is often justified with a certain conception of public interest. Policies, programs and particular projects pursued under the name of development may distribute the costs and benefits of “development” unevenly, thus, development does not necessarily benefit everyone in the same way. There is one big research question that motivates this dissertation: Is it possible for urban redevelopment to occur in the existing residents’ terms that actually benefit them? If not, what are the obstacles to that occurring? This dissertation focuses on Turkey’s ongoing urban redevelopment program as an extreme case regarding the scope of the renewal policy and the scale of the redevelopment targets chased under a complex legislation. A comparative analysis is conducted to explore the urban renewal program implementation in three second-tier cities (Adana, Bursa, and Izmir). -

Athens-Clarke County, Georgia Design Guidelines for Historic Districts and Landmark Properties *

MANDATORY SUBMITTAL SECTION VI – PROPOSAL FORMS A: PROPOSAL FORM Proposal of (Hereinafter called "Developer"), organized and existing under the laws of the State of , doing business as *. In compliance with the RFP issued for this project, the Developer hereby proposes and agrees to perform and furnish all work for the requirement known as RFP #00001 HOTEL DEVELOPER in strict accordance with the Proposal Documents, within the time set forth therein, and at the price proposed above. By submission of this Proposal, the Developer certifies, and in the case of a joint Offer, each party thereto certifies as to its own organization that: 1. The Developer has examined and carefully studied the Proposal Documents and the Addenda, receipt of all of which is hereby acknowledged at Attachment I. 2. The Developer agrees that this proposal may not be revoked or withdrawn after the time set for the opening of proposals but shall remain open for acceptance for a period of sixty (60) days following such time. Company: Contact: Address: Phone: Fax Email: Authorized Representative/Title Authorized Representative Date (print or type) (Signature) MANDATORY SUBMITTAL SECTION VI – PROPOSAL FORMS B: MINORITY BUSINESS ENTERPRISE IDENTIFICATION FORM THE UNIFIED GOVERNMENT OF ATHENS -CLARKE COUNTY - MINORITY BUSINESS ENTERPRISE IDENTIFICATION FORM IS THIS BUSINESS 51% OWNED, OPERATED AND CONTROLLED ON A DAILY BASIS BY ONE OR MORE MINORITIES AS OUTLINED IN THE UNIFIED GOVERNMENT’S MINORITY BUSINESS ENTERPRISE POLICY? οYES ARE YOU CURRENTLY CERTIFIED WITH THE UNIFIED GOVERNMENT AS A MINORITY BUSINESS ENTERPRISE FIRM? οYES οNO The Unified Government of Athens-Clarke County adopted a Minority Business Enterprise Policy on November 1, 1994. -

Revised Bylaws Passed Annual Meeting on Friday

Vol. 13, No. 5 April 2016 TIMES REVISED BYLAWS PASSED The Bylaws Committee (Lee Albright, Betty Jean Craige, Katy Crapo, Pat McAlexander, Don Schneider, Barbara Timmons, and chair Bill Alworth) has worked since September on updating the content and the language of OLLI bylaws. Significant BYLAWS content changes include elimination of the office of Vice President, changing the terms of the secretary and treasurer to two years instead of one, classifying Learning in Retirement, Inc. committees as either Governance (responsible to the Board of Directors) or Doing Business as Operating (responsible to the Executive Director), and making sure the bylaws The Osher Lifelong Learning Institute do not conflict with the Memorandum of Agreement between OLLI@UGA and at The University of Georgia the UGA College of Education.The bylaws can now be amended by a three- River’s Crossing fourths majority vote of the Board of Directors at any regularly scheduled 850 College Station Road meeting if the changes have been posted one week prior to the meeting. Athens, GA 30602-4811 The Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at The University of Georgia is dedicated to meeting the intellectual, social and Chair Bill Alworth points out that the committee’s intent was to provide a cultural needs of mature adults through lifelong learning. structure for OLLI governance without rigidly spelling out all policies and procedures—much like the U.S. Constitution. For example, the bylaws specify that the Board meet monthly but do not specify a specific day or Adopted April 11, 2016 week. The OLLI Board voted to accept these new bylaws on April 11. -

Guide to Athens, GA Flagpole.Com TABLE of CONTENTS

FREE! A G s, en e to Ath id u G 2018–2019 Celebrating 30 Years in Athens Eastside Downtown Timothy Rd. 706-369-0085 706-354-6966 706-552-1237 CREATIVE FOOD WITH A SOUTHERN ACCENT Athens Favorite Beer Selection Lunch Dinner Weekend Brunch and Favorite Fries (voted on by Flagpole Readers) Happy Hour: M-F 3-6pm Open for Lunch & Dinner 7 days a week & RESERVE YOUR TABLE NOW AT: Sunday Brunch southkitchenbar.com 247 E. Washington St. Trappezepub.com (inside historic Georgian Building) 269 N. Hull St. 706-395-6125 706-543-8997 2 2018–2019 flagpole Guide to Athens, GA flagpole.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Athens at a Glance . 4 Stage and Screen . 22 Annual Events . 9 Books and Records . 25 Athens Favorites . 11 Athens Music . .. 26 Lodging . 12 Farmers Markets and Food Trucks . 29 Art Around Town . 14 Athens and UGA Map . .31 Get Active . 17 Athens-Clarke County Map . 32 Parks and Recreation . 18 Restaurant, Bar and Club Index . 35 Specially for Kids 20 Restaurant and Bar Listings 38 . NICOLE ADAMSON UGA Homecoming Parade 2018–2019 flagpole Guide to Athens, GA Advertising Director & Publisher Alicia Nickles Instagram @flagpolemagazine Editor & Publisher Pete McCommons Twitter @FlagpoleMag Production Director Larry Tenner Managing Editor Gabe Vodicka Flagpole, Inc. publishes the Flagpole Guide to Athens every August Advertising Sales Representatives Anita Aubrey, Jessica and distributes 45,000 copies throughout the year to over 300 Pritchard Mangum locations in Athens, the University of Georgia campus and the Advertising Designer Anna LeBer surrounding area. Please call the Flagpole office or email class@ Contributors Blake Aued, Hillary Brown, Stephanie Rivers, Jessica flagpole.com to arrange large-quantity deliveries of the Guide.