Child Protection Evidence Systematic Review on Visceral Injuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surgical Case Conference

Surgical Case Conference HENRY R. GOVEKAR, M.D. PGY-2 UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO HOSPITAL Objectives Introduce Patient Hospital Course Management of Injuries Decisions to make Outcome History and Physical 50y/o M who was transferred to Denver Health on post injury day #3. Patient involved in motorcycle collision in Vail; admit to local hospital. Patient riding with female companion, tight turn, laid down the bike on road, companion landing on top of patient. Companion suffered minor injuries including abrasions and knee pain History and Physical Our patient – c/o Right shoulder pain, left flank pain PMH: GERD; peptic ulcer PSH: hx of surgery for intractable ulcerative disease – distal gastrectomy with Billroth I, ? Of revision to Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy Meds: prilosec Social: denies tobacco; quit ETOH 13 years ago after MVC; denies IVDA NKDA History and Physical Exam per OSH: a&ox3, minor distress HR 110’s, BP 130/70’s, on NRB mask with sats 98% Multiple abrasions on scalp, arms , knees c/o right arm pain, left sided flank pain No other obvious injuries After fluid resuscitation – HD stable Sent to CT for abd/pelvis Post 10th rib fx Grade 3 splenic laceration Spleen Injury Scale Grade I Injury Grade IV injury http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/373694-media Grade V injury http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/373694-media What should our plan be? Management of Splenic Injuries Stable vs. Unstable Unstable – OR Stable – abd CT scan CT scan Other significant injury – OR Documented splenic injury Grade I, -

Chest Trauma in Children

Chest Trauma In Children Donovan Dwyer MBBCh, DCH, DipPEC, FACEM Emergency Physician St George and Sydney Children’s Hospitals Director of Trauma, Sydney Children’s Hospital Disclaimer • This cannot be comprehensive • Trying to give trauma clinicians a perspective on paediatric differences • Trying to give emergency paediatric clinicians a perspective on trauma challenges • The format will focus on take home salient points related to ED dx and management • I may gloss over slides with more detail and references to keep to time • As most chest mortality is in the 12-15 yr age group, where paediatric evidence is low, I have looked to adult evidence OVERVIEW • Size of the problem • Common injuries – pitfalls and tips • Less common injuries – where recognition and time is critical • Blunt vs penetrating • The Chest in Traumatic Cardiac Arrest Size of the problem • Overall paediatric trauma in Australasia is low volume • Parents take injured children to nearest hospital for primary care • Prehospital services will divert to nearest facility with critically injured children Chest Injury • RV of Victorian State Trauma Registry in 2001–2007 = 204 cases • < 1/week • Blunt trauma - 96% • motor vehicle collisions (75%) • pedestrian (26%) • vehicle occupants (33%) Size of the problem • Common injuries – combined 50% of the time • lung contusion (66%) • haemo/pneumothorax (32%) • rib fracture (23%). • Associated multiple organ injury 90% • head (62%) • abdominal (50%) • Management conservative/supportive > 80% • Surgical • 11 cases (7%) treated surgically • 30% invasive • 18 cases(11%) had insertion of intercostal catheters (ICC). • Epidemiology of major paediatric chest trauma, Sumudu P Samarasekera ET AL, Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health (2009) International • 85 % Blunt –MVA – 45% • Ped vs car – 20% • Falls – 10% • NAI – 7% • Penetrating 15% • Mortality • Cooper A. -

Helping Young Children Who Have Experienced Trauma: Policies and Strategies for Early Care and Education

Helping Young Children Who Have Experienced Trauma: Policies and Strategies for Early Care and Education April 2017 Authors Acknowledgments Jessica Dym Bartlett, MSW, PhD We are grateful to our reviewers, Elizabeth Jordan, Senior Research Scientist Jason Lang, Robyn Lipkowitz, David Murphey, Child Welfare/Early Childhood Development Cindy Oser, and Kathryn Tout. We also thank Child Trends the Alliance for Early Success for its support of this work. Sheila Smith, PhD Director, Early Childhood National Center for Children in Poverty Mailman School of Public Health Columbia University Elizabeth Bringewatt, MSW, PhD Research Scientist Child Welfare Child Trends Copyright Child Trends 2017 | Publication # 2017-19 Helping Young Children Who Have Experienced Trauma: Policies and Strategies for Early Care and Education Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................1 Introduction ..........................................................................3 What is Early Childhood Trauma? ................................. 4 The Impacts of Early Childhood Trauma ......................5 Meeting the Needs of Young Children Who Have Experienced Trauma ...........................................................7 Putting It Together: Trauma-Informed Care for Young Children .....................................................................8 Promising Strategies for Meeting the Needs of Young Children Exposed to Trauma ..............................9 Recommendations ........................................................... -

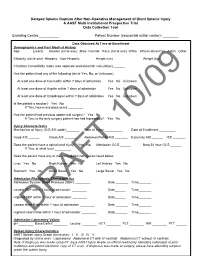

Delayed Splenic Rupture After Non-Operative Management of Blunt Splenic Injury a AAST Multi-Institutional Prospective Trial Data Collection Tool

Delayed Splenic Rupture After Non-Operative Management of Blunt Splenic Injury A AAST Multi-Institutional Prospective Trial Data Collection Tool Enrolling Center:__________ Patient Number (sequential within center): ________ Data Obtained At Time of Enrollment Demographics and Past Medical History Age: ______ (years) Gender (circle one): Male Female Race (circle one): White African-American Asian Other Ethnicity (circle one): Hispanic Non-Hispanic Height (cm) _______ Weight (kg) ______ Charlson Comorbidity Index (see separate worksheet for calculation) ______ Has the patient had any of the following (circle Yes, No, or Unknown): At least one dose of Coumadin within 7 days of admission Yes No Unknown At least one dose of Aspirin within 7 days of admission Yes No Unknown At least one dose of Clopidrogrel within 7 days of admission Yes No Unknown Is the patient a smoker? Yes No If Yes, how many pack-years ________ Has the patient had previous abdominal surgery? Yes No If Yes, is the only surgery patient has had laproscopic? Yes No Injury Characteristics Mechanism of Injury (ICD-9 E-code):_______ Date of Injury __________ Date of Enrollment _________ Head AIS ______ Chest AIS _______ Abdomen/Pelvis AIS _______ Extremity AIS ______ ISS _______ Does the patient have a spinal cord injury? Yes No Admission GCS ______ Best 24 hour GCS ______ If Yes, at what level _________ Does the patient have any of the intra-abdominal injuries listed below: Liver Yes No Right Kidney Yes No Left Kidney Yes No Stomach Yes No Small Bowel Yes No Large Bowel Yes -

DCMC Emergency Department Radiology Case of the Month

“DOCENDO DECIMUS” VOL 6 NO 2 February 2019 DCMC Emergency Department Radiology Case of the Month These cases have been removed of identifying information. These cases are intended for peer review and educational purposes only. Welcome to the DCMC Emergency Department Radiology Case of the Month! In conjunction with our Pediatric Radiology specialists from ARA, we hope you enjoy these monthly radiological highlights from the case files of the Emergency Department at DCMC. These cases are meant to highlight important chief complaints, cases, and radiology findings that we all encounter every day. PEM Fellowship Conference Schedule: February 2019 If you enjoy these reviews, we invite you to check out Pediatric Emergency Medicine Fellowship 6th - 9:00 First Year Fellow Presentations Radiology rounds, which are offered quarterly 13th - 8:00 Children w/ Special Healthcare Needs………….Dr Ruttan 9:00 Simulation: Neuro/Complex Medical Needs..Sim Faculty and are held with the outstanding support of the 20th - 9:00 Environmental Emergencies………Drs Remick & Munns Pediatric Radiology specialists at Austin Radiologic 10:00 Toxicology…………………………Drs Earp & Slubowski 11:00 Grand Rounds……………………………………….…..TBA Association. 12:00 ED Staff Meeting 27th - 9:00 M&M…………………………………..Drs Berg & Sivisankar If you have and questions or feedback regarding 10:00 Board Review: Trauma…………………………..Dr Singh 12:00 ECG Series…………………………………………….Dr Yee the Case of the Month, feel free to email Robert Vezzetti, MD at [email protected]. This Month: Let’s fall in love with learning from a very interesting patient. His story, though, is pretty amazing. Thanks to PEM Simulations are held at the Seton CEC. -

Basics of Pediatric Trauma Critical Care Management

Basics of Pediatric Trauma Critical Care Management Chapter 39 BASICS OF PEDIATRIC TRAUMA CRITICAL CARE MANAGEMENT † CHRISTOPHER M. WATSON, MD, MPH,* AND DOWNING LU, MPHL, MD, MPH INTRODUCTION RECEIVING THE PEDIATRIC CRITICAL CARE PATIENT PULMONARY SUPPORT AND MECHANICAL VENTILATION IN PEDIATRIC TRAUMA PATIENTS PEDIATRIC HEMODYNAMIC PRINCIPLES IN TRAUMA POSTOPERATIVE FLUID MANAGEMENT AND NUTRITION PEDIATRIC PAIN AND SEDATION MANAGEMENT HEAD AND SPINAL CORD TRAUMA IN CHILDREN FEVER AND INFECTION HEMATOLOGIC ISSUES PEDIATRIC BURN CARE PEDIATRIC TRANSPORT PRINCIPLES SUMMARY Attachment 1. COMMON Pediatric EMERGENCY Resuscitation DOSING ATTACHMENT 2. PEDIATRIC DOSING FOR SELECTED CATEGORIES OF COMMONLY USED MEDICATIONS *Lieutenant Commander, Medical Corps, US Navy; Pediatric Intensivist, Department of Pediatrics, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, 8901 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, Maryland 20889 †Lieutenant Colonel, Medical Corps, US Army; Chief of Pediatric Critical Care, Department of Pediatrics, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, 8901 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, Maryland 20889 401 Combat Anesthesia: The First 24 Hours INTRODUCTION Children represent a particularly vulnerable seg- permanently injured.2 Review of recent military con- ment of the population and have increasingly become flicts suggests that in Operations Enduring Freedom more affected by armed conflict during the last cen- and Iraqi Freedom, more than 6,000 children pre- tury. As modern warfare technologies advance and sented to combat support hospitals by -

ACR Appropriateness Criteria: Head Trauma-Child

Revised 2019 American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Head Trauma-Child Variant 1: Child. Minor acute blunt head trauma. Very low risk for clinically important brain injury per PECARN criteria. Excluding suspected abusive head trauma. Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level Arteriography cerebral Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢☢ CT head with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ CT head without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢☢ CT head without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ CTA head with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢☢ MRA head without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O MRA head without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O MRI head without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O MRI head without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O Radiography skull Usually Not Appropriate ☢ Variant 2: Child. Minor acute blunt head trauma. Intermediate risk for clinically important brain injury per PECARN criteria. Excluding suspected abusive head trauma. Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level CT head without IV contrast May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢ Arteriography cerebral Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢☢ CT head with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ CT head without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢☢ CTA head with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢☢ MRA head without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O MRA head without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O MRI head without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O MRI head without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O Radiography skull Usually Not Appropriate ☢ ACR Appropriateness Criteria® 1 Head Trauma-Child Variant 3: Child. Minor acute blunt head trauma. High risk for clinically important brain injury per PECARN criteria. -

Spleen Trauma

Guideline for Management of Spleen Trauma Minor injury HDS Ward Observation Grade I - II STICU Observation Hemodynamically Contrast- Moderate Stable enhanced CTS Injury +/- local HDS exploration in SW Grade III-V Contrast extravasation Angioembolization (A/E) Pseudoaneurysm Spleen Injury Ongoing bleeding HDS DeteriorationGrade I - II Unstable Unsuccessful or rebleeding Hemodynamically Splenectomy Repeat eFAST Positive Laparotomy eFAST Unstable Unstable CBC, ABG, Lactate POC INR Stable Type and Cross Splenic salvage or splenectomy Negative Positive Consider DPA Negative Evaluate for other causes of instability Guideline for Management of Spleen Trauma -NOM in splenic injuries is contraindicated in the setting of unresponsive hemodynamic instability or other indicates for laparotomy (peritonitis, hollow organ injuries, bowel evisceration, impalement) -AG/AE may be considered the first-line intervention in patients with hemodynamic stability and arterial blush on CT scan irrespective from injury grade - Age above 55 years old, high ISS, and moderate to severe splenic injuries are prognostic factors for NOM failure. -Age above 55 years old alone, large hemoperitoneum alone, hypotension before resuscitation, GCS < 12 and low-hematocrit level at the admission, associated abdominal injuries, blush at CT scan, anticoagulation drugs, HIV disease, drug addiction, cirrhosis, and need for blood transfusions should be taken into account, but they are not absolute contraindications for NOM but are at higher risk of failure and STICU observation is -

Management of Adult Blunt Splenic Trauma

Review Article The Journal of TRAUMA Injury, Infection, and Critical Care Western Trauma Association (WTA) Critical Decisions in Trauma: Management of Adult Blunt Splenic Trauma Frederick A. Moore, MD, James W. Davis, MD, Ernest E. Moore, Jr., MD, Christine S. Cocanour, MD, Michael A. West, MD, and Robert C. McIntyre, Jr., MD 09/30/2020 on BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3Ypodx1mzGi19a2VIGqBjfv9YfiJtaGCC1/kUAcqLCxGtGta0WPrKjA== by http://journals.lww.com/jtrauma from Downloaded J Trauma. 2008;65:1007–1011. Downloaded his is a position article from members of the Western geons were focused on perfecting operative splenic salvage from 1–3 http://journals.lww.com/jtrauma Trauma Association (WTA). Because there are no pro- techniques, the pediatric surgeons provided convincing Tspective randomized trials, the algorithm (Fig. 1) is evidence that the best way to salvage the spleen was not to based on the expert opinion of WTA members and published operate.4–6 Adult trauma surgeons were slow to adopt non- observational studies. We recognize that variability in deci- operative management (NOM) because early reports of its sion making will continue. We hope this management algo- use in adults documented a 30% to 70% failure rate of which by rithm will encourage institutions to develop local protocols two-thirds underwent total splenectomy.7–10 There was also a BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3Ypodx1mzGi19a2VIGqBjfv9YfiJtaGCC1/kUAcqLCxGtGta0WPrKjA== based on the resources that are available and local expert concern about missing serious concomitant intra-abdominal consensus opinion to apply the safest, most reliable manage- injuries.11–13 However, with increasing experience with NOM, ment strategies for their patients. What works at one institu- recognition that negative laparotomies caused significant tion may not work at another. -

Delayed Complications of Nonoperative Management of Blunt Adult Splenic Trauma

PAPER Delayed Complications of Nonoperative Management of Blunt Adult Splenic Trauma Christine S. Cocanour, MD; Frederick A. Moore, MD; Drue N. Ware, MD; Robert G. Marvin, MD; J. Michael Clark, BS; James H. Duke, MD Objective: To determine the incidence and type of de- Results: Patients managed nonoperatively had a sig- layed complications from nonoperative management of nificantly lower Injury Severity Score (P<.05) than adult splenic injury. patients treated operatively. Length of stay was signifi- cantly decreased in both the number of intensive care Design: Retrospective medical record review. unit days as well as total length of stay (P<.05). The number of units of blood transfused was also signifi- Setting: University teaching hospital, level I trauma center. cantly decreased in patients managed nonoperatively (P<.05). Seven patients (8%) managed nonoperatively Patients: Two hundred eighty patients were admitted developed delayed complications requiring interven- to the adult trauma service with blunt splenic injury dur- tion. Five patients had overt bleeding that occurred at ing a 4-year period. Men constituted 66% of the popu- 4 days (3 patients), 6 days (1 patient), and 8 days (1 lation. The mean (±SEM) age was 32.2±1.0 years and the patient) after injury. Three patients underwent sple- mean (±SEM) Injury Severity Score was 22.8±0.9. Fifty- nectomy, 1 had a splenic artery pseudoaneurysm nine patients (21%) died of multiple injuries within 48 embolization, and 1 had 2 areas of bleeding emboliza- hours and were eliminated from the study. One hun- tion. Two patients developed splenic abscesses at dred thirty-four patients (48%) were treated operatively approximately 1 month after injury; both were treated within the first 48 hours after injury and 87 patients (31%) by splenectomy. -

Head Injury Pediatric After-Hours Version - Standard - 2015

Head Injury Pediatric After-Hours Version - Standard - 2015 DEFINITION Injuries to the head including scalp, skull and brain trauma INITIAL ASSESSMENT QUESTIONS 1. MECHANISM: "How did the injury happen?" For falls, ask: "What height did he fall from?" and "What surface did he fall against?" (Suspect child abuse if the history is inconsistent with the child's age or the type of injury.) 2. WHEN: "When did the injury happen?" (Minutes or hours ago) 3. NEUROLOGICAL SYMPTOMS: "Was there any loss of consciousness?" "Are there any other neurological symptoms?" 4. MENTAL STATUS: "Does your child know who he is, who you are, and where he is? What is he doing right now?" 5. LOCATION: "What part of the head was hit?" 6. SCALP APPEARANCE: "What does the scalp look like? Are there any lumps?" If so, ask: "Where are they? Is there any bleeding now?" If so, ask: "Is it difficult to stop?" 7. SIZE: For any cuts, bruises, or lumps, ask: "How large is it?" (Inches or centimeters) 8. PAIN: "Is there any pain?" If so, ask: "How bad is it?" 9. TETANUS: For any breaks in the skin, ask: "When was the last tetanus booster?" - Author's note: IAQ's are intended for training purposes and not meant to be required on every call. TRIAGE ASSESSMENT QUESTIONS Call EMS 911 Now [1] Major bleeding (actively dripping or spurting) AND [2] can't be stopped FIRST AID: apply direct pressure to the entire wound with a clean cloth CA: 50, 10 [1] Large blood loss AND [2] fainted or too weak to stand R/O: impending shock FIRST AID: have child lie down with feet elevated CA: 50, -

Firearm-Related Musculoskeletal Injuries in Children and Adolescents

Review Article Firearm-related Musculoskeletal Injuries in Children and Adolescents Abstract Cordelia W. Carter, MD Firearm injuries are a major cause of morbidity and mortality among Melinda S. Sharkey, MD children and adolescents in the United States and take financial and emotional tolls on the affected children, their families, and society as a Felicity Fishman, MD whole. Musculoskeletal injuries resulting from firearms are common and may involve bones, joints, and neurovascular structures and other soft tissues. Child-specific factors that must be considered in the setting of gunshot injuries include physeal arrest and lead toxicity. Understanding the ballistics associated with various types of weaponry is useful for guiding orthopaedic surgical treatment. Various strategies for preventing these injuries range from educational programs to the enactment of legislation focused on regulating guns and gun ownership. Several prominent medical societies whose members routinely care for children and adolescents with firearm- related injuries, including the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Pediatric Surgical Association, have issued policy statements aimed at mitigating gun-related injuries and deaths in children. Healthcare providers for young patients with firearm-related musculoskeletal injuries must appreciate the full scope of this important public health issue. From the Department of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, Yale School of ecently, firearm-related injuries school campus or grounds, as Medicine, New Haven, CT. Dr. Carter in children and adolescents have documented by the press and con- or an immediate family member R serves as a board member, owner, been featured prominently in the firmed through further inquiries with officer, or committee member of the media.