Pony Distress: Using ESPN's 30FOR30 Films to Teach Cartel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Football Coaching Records

FOOTBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) Coaching Records 5 Football Championship Subdivision (FCS) Coaching Records 15 Division II Coaching Records 26 Division III Coaching Records 37 Coaching Honors 50 OVERALL COACHING RECORDS *Active coach. ^Records adjusted by NCAA Committee on Coach (Alma Mater) Infractions. (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct. Note: Ties computed as half won and half lost. Includes bowl 25. Henry A. Kean (Fisk 1920) 23 165 33 9 .819 (Kentucky St. 1931-42, Tennessee St. and playoff games. 44-54) 26. *Joe Fincham (Ohio 1988) 21 191 43 0 .816 - (Wittenberg 1996-2016) WINNINGEST COACHES ALL TIME 27. Jock Sutherland (Pittsburgh 1918) 20 144 28 14 .812 (Lafayette 1919-23, Pittsburgh 24-38) By Percentage 28. *Mike Sirianni (Mount Union 1994) 14 128 30 0 .810 This list includes all coaches with at least 10 seasons at four- (Wash. & Jeff. 2003-16) year NCAA colleges regardless of division. 29. Ron Schipper (Hope 1952) 36 287 67 3 .808 (Central [IA] 1961-96) Coach (Alma Mater) 30. Bob Devaney (Alma 1939) 16 136 30 7 .806 (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct. (Wyoming 1957-61, Nebraska 62-72) 1. Larry Kehres (Mount Union 1971) 27 332 24 3 .929 31. Chuck Broyles (Pittsburg St. 1970) 20 198 47 2 .806 (Mount Union 1986-2012) (Pittsburg St. 1990-2009) 2. Knute Rockne (Notre Dame 1914) 13 105 12 5 .881 32. Biggie Munn (Minnesota 1932) 10 71 16 3 .806 (Notre Dame 1918-30) (Albright 1935-36, Syracuse 46, Michigan 3. -

Eastern Progress 1990-1991 Eastern Progress

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Eastern Progress 1990-1991 Eastern Progress 1-17-1991 Eastern Progress - 17 Jan 1991 Eastern Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: http://encompass.eku.edu/progress_1990-91 Recommended Citation Eastern Kentucky University, "Eastern Progress - 17 Jan 1991" (1991). Eastern Progress 1990-1991. Paper 16. http://encompass.eku.edu/progress_1990-91/16 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Eastern Progress at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Eastern Progress 1990-1991 by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Activities Weekend weather Moo-ving art All together now Pressing on Friday: Dry afternoon, night low near 20. New faculty art exhibit E Pluribus Unum Colonels push Saturday and Sunday: features ceramics kicks off Monday to 2-1 in OVC Clear and dry, high of and photographs Page B-2 Page B-4 Page B-6 40. Low near 20. THE EASTERN PROGRESS Vol. 69/No. 16 16 pages January 17,1991 Student publication ot Eastern Kentucky University, Richmond, Ky. 40475 © The Eastern Progress, 1991 Middle Eastern War Zone A moment of silence Syria- Persian Gult X Mediterranean Sea Source: Cable News Network Progress grmphic by TERRY SEBASTIAN Coalition forces launch offensive on Iraqi targets War won't affect university, Funderburk says By Mike Royer, Tom Marshall middle of hell." and Joe Castle Late last night CNN reported the mission Candlelight vigil unites was "a blowout" with no allied losses, ac- It happened. cording to reports from CNN quotinq a At 7 p.m. -

Marcus Dupree

Marcus Dupree When Marcus Dupree played football in Philadelphia, MS, his play united the racially divided city. Dupree was one the most highly recruited high school players in the history of American football, whose phenomenal athletic speed and agility were often compared to Jim Brown and Earl Campbell. He won almost every honor available in the nation. While Dupree was still in high school, a book was written about Dupree’s nationally publicized college recruitment titled, The Courting of Marcus Dupree. Dupree committed to the University of Oklahoma in 1982. Sports Illustrated featured Marcus on the cover in 1983 and his outstanding running plays were often the topic of nightly national news broadcasts. On January 1, 1983 Oklahoma played Arizona State in the Fiesta Bowl where Dupree was named the MVP. Although he only played half of the game and had four injuries, Dupree set and still holds the Fiesta Bowl rushing record of 239 yards. In 1984 the USFL’s New Orleans Breakers signed Dupree at age 19 and made him the highest paid player in football. In his first year with the Breakers, Marcus gained 684 yards on 145 carries with 9 touchdowns. Unfortunately, a severe knee injury forced Dupree to leave the game. Amazingly, after an unprecedented five and a half year hiatus from professional football Dupree’s passion and determination were the catalysts for him to earn a tryout with the Los Angeles Rams. In 1990, Dupree made the team and was named, “Comeback Player of the Year.” In spite of a respectable sophomore season with the Rams, Dupree was released. -

Democratic Dilemma the LBJ Biography, Part II Runoff

Death Penalty Politics Pg. 6 A JOURNAL OF FREE VOICES APRIL 6, 1990 • $1.50 ALAN POGUE Democratic Dilemma Ronnie Dugger Considers the Governor's Race The LBJ Biography, Part II Robert Sherrill on Caro's Means of Ascent Runoff Endorsements Ann Richards, Nikki Van Hightower, Hector Uribe, Et Al. Also: Bill Adler Reviews The Ambition and the Power ,, = -1=11141:1177.74-7,_ ILA EDITORIALS . ..•121111.........z, Itall iti Mill - raillb, THE TEXAS Equity Deferred 111P server ITHIN MOMENTS of adjournment A JOURNAL OF FREE VOICES W on the final Thursday of the third We will serve no group or party but will hew hard to special legislative session several members the truth as we find it and the right as we see it. We of the House Mexican American Caucus had are dedicated to the whole truth, to human values gathered in a. circle around the desk of San above all interests, to the rights of 'humankind as the foundation of democracy; we will rake orders from Antonio Rep. Greg Luna. They were joined none but our own conscience, and never will we over- by Houston Rep. Larry Evans, chair of the look or misrepresent the truth to serve the interests of Black Caucus. Education reform, for this the powerful or cater to the ignoble in the human spirit. session, was dead. But this group was still in Writers are responsible for their own work, but not for anything they have not themselves written, and in denial. "You have to do more than oppose publishing them we do not necessarily imply that we legislation," Austin Rep. -

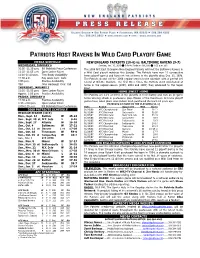

Patriots Host Ravens in Wild Card Playoff Game

PATRIOTS HOST RAVENS IN WILD CARD PLAYOFF GAME MEDIA SCHEDULE NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (10-6) vs. BALTIMORE RAVENS (9-7) WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 6 Sunday, Jan. 10, 2010 ¹ Gillette Stadium (68,756) ¹ 1:00 p.m. EDT 10:50 -11:10 a.m. Bill Belichick Press Conference The 2009 AFC East Champion New England Patriots will host the Baltimore Ravens in 11:10 -11:55 a.m. Open Locker Room a Wild Card playoff matchup this Sunday. The Patriots have won 11 consecutive 11:10-11:20 p.m. Tom Brady Availability home playoff games and have not lost at home in the playoffs since Dec. 31, 1978. 11:30 a.m. Ray Lewis Conf. Calls The Patriots closed out the 2009 regular-season home schedule with a perfect 8-0 1:05 p.m. Practice Availability record at Gillette Stadium. The first three times the Patriots went undefeated at TBA John Harbaugh Conf. Call home in the regular-season (2003, 2004 and 2007) they advanced to the Super THURSDAY, JANUARY 7 Bowl. 11:10 -11:55 p.m. Open Locker Room HOME SWEET HOME Approx. 1:00 p.m. Practice Availability The Patriots are 11-1 at home in the playoffs in their history and own an 11-game FRIDAY, JANUARY 8 home winning streak in postseason play. Eleven of the franchise’s 12 home playoff 11:30 a.m. Practice Availability games have taken place since Robert Kraft purchased the team 16 years ago. 1:15 -2:00 p.m. Open Locker Room PATRIOTS AT HOME IN THE PLAYOFFS (11-1) 2:00-2:15 p.m. -

The University of Texas System

The University ofTexasat Arlington The University of Texas Health Science Center at Dallas The Universi1y of Texas at Austin The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston The University of Texas at Dallas The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston The University of Texas at El Paso The University of Texas System Cancer Center The University of Texas of the Permian Basin The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio The University of Texas at San A monio The University of Texas Health Center at Tyler The University of Texas at Tyler The University of Texas Institute of Texan Cultures at San Antonio THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SYSTEM 601 COLORADO STREET AUSTIN, TEXAS 78701 Office of the Chancellor Janey Briscoe of Uvalde was appointed to a six-year term on The University of Texas System Board of Regents by Governor Bill Clements on January 9, 1981. She was elected Vice-Chairman of the U.T. Board of Regents on April 15, 1983. Mrs. Briscoe received both her B.S. and M.S. degrees in education from The University of Texas at Austin. She is a graduate of Austin High School, Austin, Texas. Mrs. Briscoe, wife of the former Governor Dolph Briscoe, took part in numerous public service activities during the six years she served as First Lady of Texas. She was chairman of The Generation Connection, which coordinated the efforts of human welfare and service agencies to increase public awareness of the needs of mature Texas citizens. She also founded and headed the First Lady 1 s Volunteer Program which helped coordinate the activities of volunteer groups across the State. -

Dale Hansen , Sports Anchor, WFAA 8

The Rotary Club THE HUB of Park Cities Volume 71, Number 25 www.parkcitiesrotary.org February 14, 2020 Serving to Make a Difference Since 1948 TODAY’S PROGRAM Program Chairs of the Day: Jeff Brady Dale Hansen, Sports Anchor, WFAA 8 Dale Hansen is the weeknight sports anchor during the 10 Hansen's other awards and honors include: p.m. newscast on WFAA, Channel 8 in Dallas Texas. He also • Dallas Peace and Justice Center's 2019 Inspiration Award hosts Dale Hansen's Sports Special on Sundays at 10:35 p.m.. • Hero of Hope Award from the Cathedral of Hope Church He's well known for his acclaimed "Unplugged" segments. • Peacemaker Award from the Turtle Creek Chorale Hansen began his career as a radio disc jockey and opera- • Children's Hero Award from TexProtects tions manager in Newton, Iowa. This was followed by a job as a • Distinguished Professional Achievement Award from the UNT sports reporter at KMTV in Omaha, Nebraska. Hansen's first job School of Journalism in Dallas was with KDFW-TV (Channel 4). He joined WFAA-TV in • Communicator of the Year by the National Speech and Debate 1983. Association In 1987, Hansen was honored with the George Foster Pea- • Recipient of over 20 Lone Star EMMY Awards body Award for Distinguished Journalism. That same year, he won • Sportscaster of the Year on two occasions by the Associated the duPont-Columbia Award for his contribution to the investiga- Press tion of SMU's football program. As a result of this investigation, • Texas Sportscaster of the Year on three occasions by the the NCAA prohibited SMU from fielding a football program in 1987. -

WHITE, CLEMENTS a Diitles WORTH of DIFFERENCE?

'TEXAS 13 SERVER October I 1982 A Journal of Free Voices 750 WHITE, CLEMENTS A DIItleS WORTH OF DIFFERENCE? Kevin Kreneck By Joe Holley By Paul Sweeney with the White campaign with the Clements campaign N AN OLD MOVIE poster on N THIS TYPICALLY wind- the wall just above the steam On The Inside blown, sun-drenched Panhandle trays of bubbly Swedish meat- morning, a small caravan of 0 shiny cars and vans waiting outside balls and bacon-wrapped chicken livers, Gene Autry smiled his perpetual ENDORSEMENTS Amarillo's Hilton Inn pulls into line be- singing-cowboy smile. At the other end hind a big, armadillo-crunching Scout of the cramped restaurant banquet room, See Page 2 carrying Gov. Bill Clements and his wife hemmed in by a noisy crowd of well Rita. Next in line in a Mercedes is Mad wishers, the candidate for governor, Eddie Chiles and his wife Fran, a Repub- lican national committee woman. Bring- sweating in the hot glare of television MAVERICK AND THE JEWS lights, smiled his "how are ya, good to ing up the rear is the press corps, riding in Margaret Spearman's station wagon. see ya" candidate's smile and held aloft a See Page 8 store-bought jug of water. On the short drive to West Texas State Gene Autry, of course, swapped the University in Canyon, Ms. Spearman, a smiling business for an even more lucra- Clements campaign volunteer and an tive line of work, but 42-year-old Mark 8th-grade history teacher, chats about (Continued on Page 12) (Continued on Page 15) •THE OBSERVER'S POSITION • HIS YEAR, in an exercise that is and it stands to reason that a straight- lieutenant governor, that the two top unusual in the 27-year history of ticket strategy this year enhances the Democratic nominees must be clearly T the Texas Observer, we urge our chances of these four candidates. -

Editorial: a Tale of Two Banks

1 Complimentary to churches ft/if* < / V // and community groups priority ©jijwrtumttj Jim* 2730 STEMMONS FRWY STE. 1202 TOWER WEST, DALLAS, TEXAS 75207 ©ov VOLUME 5, NO. 6 June, 1996 TPA Dallas Cowboys' star receiver Michael irvin joins a long list of other prominent African American sports stars flayed by the media. Are they unfair targets? Holiday with a Difference: Our annual Editorial: The reasons for and against bachelor of A tale of celebrating Juneteenth the year two banks vary within the community entry form From The Editor Chris Pryer ^ photo by Derrtck Walters Tike real issue . Just when it seemed that the bank statement of intent is called accountabil extol the virtues of our religious leaders The African American community ing community had gotten about as ity. Once you open your mouth, then and the on-going commitment to the continues to feel powerless, disenfran strange as possible, the paradox in styles everyone knows when you succeed or African American Museum; there has chised and second class when it comes to that exists between two of our larger fail Also, the size of the goal reflects a real been very little work done within the the educational performance of its chil financial institutions struck. While most level of thought and consideration of the lending arena by the bank. While the sup dren. Its inherent distrust of Whites of the banks still have a way to go before real need and capacity to handle this level port of the clergy and the museum are makes for the kind of polarization we are reaching perfection, there has been a of credit activity. -

Saturday Listings Sunday Listings

6 – THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 10, 2020 GAINESVILLE DAILY REGISTER SATURDAY LISTINGS SEPTEMBER 12 PRIME TIME S1 – DISH NETWORK S2 - DIRECTV 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM S1S2 Fox 4 News Saturday (N) MLB Baseball Houston Astros at Los Angeles Dodgers Site: Dodger Stadium -- Los Angeles, Calif. (L) Fox 4 News at 9:00 p.m. (N) Labor of Love (4) "10 Things Kristy 4 4 KDFW (4) Likes About You" NBC 5 News at Wingstop NHL Hockey Stanley Cup Playoffs (L) NBC5 News at Saturday Night Live (5) 6:00 p.m. Inside High 10:00 p.m. (N) 5 5 KXAS (5) Saturday (N) School Sports Jeopardy! Wheel Fortune FC Dallas Live MLS Soccer FC Dallas at Houston Dynamo Site: BBVA Compass NCIS: New Orleans "Powder Madam Secretary "So It Goes" (21) "Delicious (L) Stadium -- Houston, Texas (L) Keg" 21 21 KTXA (6) Destinations" Religious Programming Michael Kenneth W. The Green In Touch With Dr. Charles Perry Stone: Love Israel Israel: The (2) Youssef Hagin Room Stanley Manna-Fest With Baruch Prophetic 2 KDTN (7) Korman Connection College Football College Football Scoreboard (L) /NCAA Football Clemson at Wake Forest Site: BB&T Field -- College News 8 Entertainment Tonight (8) Scoreboard (L) Winston-Salem, N.C. (L) Football Update at Weekend 8 8 WFAA (8) Scoreboard (L) 10:00 p.m. (N) <++++ Titanic (1997, Drama) Leonardo DiCaprio, Victor Garber, Kate Winslet. Noticiero Noticias Somos cowboys (39) Telemundo 39 Telemundo Fin 39 39 KXTX (9) at 10pm (N) de semana (N) CBS 11 News at Paid Program CBS Saturday Encore Love Island: More to Love (N) 48 Hours (SP) (N) CBS 11 News Saturday at Cowboys (11) 6:00 p.m. -

Judging the Suspect-Protagonist in True Crime Documentaries

Wesleyan University The Honors College Did He Do It?: Judging the Suspect-Protagonist in True Crime Documentaries by Paul Partridge Class of 2018 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors from the College of Film and the Moving Image Middletown, Connecticut April, 2018 Table of Contents Acknowledgments…………………………………...……………………….iv Introduction ...…………………………………………………………………1 Review of the Literature…………………………………………………………..3 Questioning Genre………………………………………………………………...9 The Argument of the Suspect-protagonist...…………………………………......11 1. Rise of a Genre……………………………………………………….17 New Ways of Investigating the Past……………………………………..19 Connections to Literary Antecedents…………………..………………...27 Shocks, Twists, and Observation……………………………..………….30 The Genre Takes Off: A Successful Marriage with the Binge-Watch Structure.........................................................................34 2. A Thin Blue Through-Line: Observing the Suspect-Protagonist Since Morris……………………………….40 Conflicts Crafted in Editing……………………………………………...41 Reveal of Delayed Information…………………………………………..54 Depictions of the Past…………………………………………………….61 3. Seriality in True Crime Documentary: Finding Success and Cultural Relevancy in the Binge- Watching Era…………………………………………………………69 Applying Television Structure…………………………………………...70 (De)construction of Innocence Through Long-Form Storytelling……….81 4. The Keepers: What Does it Keep, What Does ii It Change?..............................................................................................95 -

2018-19 Missouri Valley Conference News Release Missouri Valley Conference MVC Contact 1818 Chouteau Ave

2018-19 Missouri Valley Conference News Release Missouri Valley Conference MVC Contact 1818 Chouteau Ave. ▪ St. Louis, MO 63103 Mike Kern ([email protected]) Phone: 314-444-4300 Fax: 314-444-4333 Associate Commissioner for Communications Website: www.mvc-sports.com Office: 314-444-4300 x 4326 Cell: 314-435-4779 October 2, 2018 ▪ For Immediate Release www.mvc-sports.com MISSOURI VALLEY UNVEILS 100-LIVE EVENT PACKAGE ON ESPN NETWORKS League Clears Contests on ESPN2, ESPNU and The Valley on ESPN during 2018-19 Academic Year ST. LOUIS -- Celebrating its 112th Non-conference games from the Classic. Each school will participate in season, the Missouri Valley Conference Mountain West-Missouri Valley Challenge three games with every contest being will have an exclusive 100-event package will also be shown, featuring 2018 NCAA delivered on an ESPN2, ESPNU or on ESPN networks during the 2018-19 Final Four participant Loyola playing host ESPN3. academic year, Commissioner Doug Elgin to 2018 NCAA Sweet Sixteen qualifier Missouri State will compete in the Hall announced today. Nevada on Tuesday, Nov. 27, at 7 p.m. of Fame Classic in Kansas City, Missouri, The Valley, which enters the fifth year Central on ESPNEWS. with both its game being shown on either of a 10-year agreement with ESPN, will On Saturday, Dec. 1, a day-night ESPN2 or ESPNU. clear 37 men’s basketball matchups twinbill occurs on The Valley on ESPN, as In terms of regular-season men’s on ESPN networks -- ESPN2, ESPNU, Illinois State entertains San Diego State basketball games, the league has three ESPNEWS, SEC Network and ESPN3, as at 2 p.m.