Teachers‟ Resource Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

All London Green Grid River Cray and Southern Marshes Area Framework

All River Cray and Southern Marshes London Area Framework Green Grid 5 Contents 1 Foreword and Introduction 2 All London Green Grid Vision and Methodology 3 ALGG Framework Plan 4 ALGG Area Frameworks 5 ALGG Governance 6 Area Strategy 8 Area Description 9 Strategic Context 10 Vision 12 Objectives 14 Opportunities 16 Project Identification 18 Project Update 20 Clusters 22 Projects Map 24 Rolling Projects List 28 Phase Two Early Delivery 30 Project Details 48 Forward Strategy 50 Gap Analysis 51 Recommendations 53 Appendices 54 Baseline Description 56 ALGG SPG Chapter 5 GGA05 Links 58 Group Membership Note: This area framework should be read in tandem with All London Green Grid SPG Chapter 5 for GGA05 which contains statements in respect of Area Description, Strategic Corridors, Links and Opportunities. The ALGG SPG document is guidance that is supplementary to London Plan policies. While it does not have the same formal development plan status as these policies, it has been formally adopted by the Mayor as supplementary guidance under his powers under the Greater London Authority Act 1999 (as amended). Adoption followed a period of public consultation, and a summary of the comments received and the responses of the Mayor to those comments is available on the Greater London Authority website. It will therefore be a material consideration in drawing up development plan documents and in taking planning decisions. The All London Green Grid SPG was developed in parallel with the area frameworks it can be found at the following link: http://www.london.gov.uk/publication/all-london- green-grid-spg . -

Bexley Growth Strategy

www.bexley.gov.uk Bexley Growth Strategy December 2017 Bexley Growth Strategy December 2017 Leader’s Foreword Following two years of detailed technical work and consultation, I am delighted to present the Bexley Growth Strategy that sets out how we plan to ensure our borough thrives and grows in a sustainable way. For centuries, Bexley riverside has been a place of enterprise and endeavour, from iron working and ship fitting to silk printing, quarrying and heavy engineering. People have come to live and work in the borough for generations, taking advantage of its riverside locations, bustling town and village centres and pleasant neighbourhoods as well as good links to London and Kent, major airports, the Channel rail tunnel and ports. Today Bexley remains a popular place to put down roots and for businesses to start and grow. We have a wealth of quality housing and employment land where large and small businesses alike are investing for the future. We also have a variety of historic buildings, neighbourhoods and open spaces that provide an important link to our proud heritage and are a rich resource. We have great schools and two world-class performing arts colleges plus exciting plans for a new Place and Making Institute in Thamesmead that will transform the skills training for everyone involved in literally building our future. History tells us that change is inevitable and we are ready to respond and adapt to meet new opportunities. London is facing unprecedented growth and Bexley needs to play its part in helping the capital continue to thrive. But we can only do that if we plan carefully and ensure we attract the right kind of quality investment supported by the funding of key infrastructure by central government, the Mayor of London and other public bodies. -

Lamorbey Planning Brief

LOCALDEVELOPMENTFRAMEWORK SUPPLEMENTARYPLANNINGDOCUMENT Lamorbey Planning Brief Adopted 8th September 2007 Listening to you, working for you www.bexley.gov.uk Lamorbey Planning Brief SPD Bexley Council LDF Foreword This Planning Brief is a Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) which has been prepared to supplement the policies and proposals of the adopted Bexley Unitary Development Plan (UDP) 2004 and The London Plan (2004), which together form the development plan for the area. It sets out detailed guidance on the potential development of the Lamorbey Swimming Pool site and surrounding area. The document has been prepared in line with the legislative requirements of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004 and associated regulations and guidance on Supplementary Planning Documents. A draft of this document was published for consultation purposes and responses were considered and taken into account in revising the Planning Brief before the final version of the document was adopted. This document is accompanied by a Sustainability Appraisal. Both documents can be viewed on the Council's website. Strategic Planning and Development Wyncham House, 207 Longlands Road Sidcup, Kent DA15 7JH Tel. 020 8308 7785 (or 7789) Bexley Council LDF Lamorbey Planning Brief SPD Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 The site and its context 4 Public car park 4 3 Opportunities and constraints 8 4 Acceptable uses 9 5 Affordable housing 10 6 Scale and density 11 7 Form of development 12 8 Access and parking 14 9 Sustainability 16 10 Other considerations 18 Trees and landscaping 18 Designing out crime 18 Refuse and recycling collection 18 Archaeology 18 Services and utilities 19 Demolition and construction 19 Bibliography 20 Lamorbey Planning Brief SPD Bexley Council LDF 3 Introduction 1 1.1 This Planning Brief has been produced to help to guide the redevelopment of the former Lamorbey swimming pool site and adjacent areas. -

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINC) Within the Borough

LONDON BOROUGH OF BEXLEY SITES OF IMPORTANCE FOR NATURE CONSERVATION REPORT DECEMBER 2016 Table of contents Bexley sites of importance for nature conservation PART I. Introduction ...................................................................................................... 5 Purpose and format of this document ................................................................................ 5 Bexley context ................................................................................................................... 5 What is biodiversity? ......................................................................................................... 6 Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINCs) ....................................................... 6 Strategic green wildlife corridors ....................................................................................... 8 Why has London Borough of Bexley adopted a new SINC assessment? ........................ 10 PART II. Site-by-site review ......................................................................................... 12 Sites of Metropolitan Importance for Nature Conservation ....................................... 13 M015 Lesnes Abbey Woods and Bostall Woods ........................................................... 13 M031 the River Thames and tidal tributaries ................................................................. 15 M041 Erith Marshes ...................................................................................................... 19 M105 -

Bexley Bird Report 2016

Bexley Bird Report 2016 Kingfisher –Crossness – Donna Zimmer Compiled by Ralph Todd June 2017 Bexley Bird Report 2016 Introduction This is, I believe, is the very first annual Bexley Bird Report, it replaces a half yearly report previously produced for the RSPB Bexley Group Newsletter/web-site and Bexley Wildlife web- site. I shall be interested in any feedback to try and measure how useful, informative or welcome it is. I suspect readers will be surprised to read that 153 different species turned up across the Borough during the 12 months of 2016. What is equally impressive is that the species reports are based on just over 13,000 individual records provided by nearly 80 different individuals. Whilst every endeavour has been made to authenticate the records they have not been subject to the rigorous analysis they would by the London Bird Club (LBC) as would normally be the case prior to publication in the annual London Bird Report (LBR). This report has also been produced in advance of the final data being available from LBC as this is not available until mid-summer the following year – it is inevitable therefore that some records might be missing. I am, however, confident no extra species would be added. The purpose of the report is four-fold:- To highlight the extraordinary range of species that reside, breed, pass through/over or make temporary stops in the Borough To hopefully stimulate a greater interest not only in the birds but also the places in which they are found. Bexley Borough has a wide range of open spaces covering a great variety of habitat types. -

Old Bexley and Sidcup Conservative Association

Rob Leitch Chairman Old Bexley and Sidcup Conservative Association Mr David Owen Review Officer (Bexley) The Local Government Boundary Commission for England 14th Floor Millbank Tower London SW1P 4QP [email protected] th 4 April 2016 Dear Mr Owen, Re: Response to the Draft Recommendations for the London Borough of Bexley Following the Local Government Boundary Commission's publication of draft boundaries for local elections in the London Borough of Bexley, I am writing in broad support of the recommendations that have been put forward. In general, the proposed boundaries improve the electoral equality of our local wards and respect the important community links that exist across so much of the Borough at present. However, I would like to draw attention to two concerns that I have which both fall within the geographical area of Old Bexley and Sidcup Conservative Association. These are: 1. That the Local Government Boundary Commission should ensure that all shops and flats on Blackfen Road and Westwood Lane are moved into Blackfen & Lamorbey Ward from the currently proposed Blendon & Penhill Ward. Explanation: Ensuring that the whole shopping area was united within one ward was put forward by the council in its submission, and the Labour Group of councillors’ proposal also proposed that the whole of the Blackfen shopping area would fall within the same ward. Changing the proposals to ensure that the shopping area becomes united would affect only a very small number of electors (approximately 50), but corrects an anomaly of the present boundaries that has caused confusion amongst a number of residents over the past few years. -

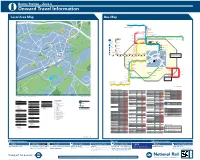

Bexley Station – Zone 6 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map N

Bexley Station – Zone 6 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map N R D 686 22 1 144 Eighty Oak 200 Footbridge R O C H E S T E R D R I V E E A S O C H E S T E R W T R O E A S T R A Y C H E S T E 20 201 R BASING DRIVE GRAVEL HILL CLOSE GRAVEL HILL CLOSE Hall Place Thamesmead W A D Thamesmead Belvedere U Y 122 A Boiler House /RZHU5RDG P 8 Town Centre T O 12 Ri O N BAYNHAM CLOSE ver West Street 40 S R h ut R Thamesmead O tle 229 Abbey Wood A HARTLANDS CLOSE D Crossway E S B12 O 50 U N T WILLOW CLOSE Hall Place H 15 Erith Town Centre R 1 River Shuttle Gardens y THAMESMEAD U ra 25 C D O r 20 e Erith Health Centre iv 1 A Blackckk PrPPrincence B R FA R M VA L E O ERITH Beths R Interchchahangangenge Grammar 1 FINSBURY WAY 3 229 School D Avenue Road L Parsonage Northumberland O 67 H A R 2 T F Manorway Heath Erith & District Hospital O R 9 W D Holiday Inn R O O TFORD 6KLQJOHZHOO5RDG &DUOWRQ5RDG N E A H D L A D 1 C L O V E 1 33 L O SE T A E 1 1 198 O A Carlton Road +DLO 5LGH L O V E L A N E U R S 52 T section 1 O 13 30 31 E N R S Barnehurst 104 ELMINGTO O 1 E R Bedonwell Road CRAYFORD D S U C A N C L 14 O H O OSE L O Old Road Greenhithe 37 R H C B E L L A Bexleyheath O R N S RIVERDALE ROAD K N T 1 Perry Street Crayford Shepherd’s Lane Dartford Waterstone Park 1 F O O T R D T Old Dartfordians Bus Garage e G E tl ALBERT ROAD R t O N R 15 u A I Association h 14 D S M W Mayplace Road Crayford Chastilian Road Horns Cross D L er A D Riv E A 35 PARKHURST ROAD E A M R O Y East Bull L E L Town Hall T L 2 Pickford Lane T T H E C L O S E O U N BEXLEYHEATH H U K S P T O 1 14 N 132 R O DARTFORD 29 A 98 Mayplace Road West Bluewater Shopping Centre 65 D 20 North Greenwich 48 1 N21 S O Foresters Crescent U E for The O2 492 T H E R I D G E T A N continues to 2 H L Bexleyheath 1 K 132 S C H 267 A Bank , Bexleyheath U T B 132 T L Bexley FC y E M 38 ra Broadway +LJKODQG5RDG E A C St. -

BEXLEY HEATH with WELLING and UPTON

DIRECTORY.] KENT. BEXLEY. 69 Jackson Arthur, beer rUr. 45 High st Reffel's Bexley Brewery Ltd. brewers Williams Joseph John, jobmaster kc. Jones In. King's Head P.H. 65 High st & wine& spirit merchants,Bourne rd 37 High street Judd George N. beer ret. Vicarage rd Relph William & Sons, auctioneers &0. Winch Richard Ford M.A.bolS' school, Keeble James Frederick, market gar- 30 High street Rugby house, Cold Blow dener, Vicarage road Roberts Edward Charles,jobmaster,64 Winser Joseph C.solicitor,Glenthorne, Kelsey Edward Bailey, butcher & far- North Gray road, Station approach Parkhurst road mer, 50 High street Sargent Alfred Henry, shopkeeper, Winter Elizabeth (Mrs.), fancy reposi. Kemp Emily (Miss), boot & shoe ma. Albert road tory & stationer, 6 High street 36 High street Savag-e Harold Francis, builder, 92 Wright Jas.plumbr. &c. 40 Hi~h st Kimpton Benj. watch ma. 12 High st North Cray road King .Tohn, smith, 73 High street & Shaw Wm. Duke, builder, Albert road HALFWAY S:r'REET. 10 Victoria road Shiers Decimus Thomas, newsagent, (Marked thus t recelv.e letterS thro' Knipe Thos. A. tailor, 82 High street 84 High street ~lItham. The remamder through Laimbeer Edwin, laundry, 7 High st Smith George Mence, grocer & oil &; Sldcup R.S.O) Laws Henry, Three Blackbirds P.H. color man, 28 High street PRIVATE RESIDENTS. Blendon Smith Henry, dairyman,Parkhurst I'd. Barnaby Jethro Julius, Jellapahar Lee William, boot mkr. Hartford rd & 16 High street Beamish Mrs. Halfway Street house Letham Thomas William, beer retIr. Smith Walt. Hy. builder, 70 High; st Clarke Major, Penhill 73 High street Stacey Thomas. -

Danson House

2014 2015 Danson House Danson House, Danson Park, Danson Road, Bexleyheath Kent, DA6 8HL www.danson.org.uk 01322 621233 01322 621246 Welcome to Danson House Danson House is a stunning Georgian villa, built for love and designed for celebration. Set in magnificent parkland overlooking the sparkling Danson lake it is the perfect location for your boutique wedding With three exquisite rooms all licensed for civil ceremonies and perfect for celebrations . The dining room: decorated in romantic gold's and pinks and the library: a splendid space, hosting the magnificent organ. These rooms are both licensed for up to 65 people and perfect for dining up to 50 people The Salon: smaller but equally as stunning. A octagonal room with sumptuous wall coverings and stylish decorations is licensed for a maximum of 45 . Danson House is available 7 days a week for civil ceremonies. Your two hour booking allows plenty of time for after ceremony drinks and photographs in this beautiful house Or choose an all inclusive package and stay on to enjoy your wedding breakfast in one of the stunning rooms . Our packages are available on Friday and Saturdays from 1st April—31st October and at anytime during the winter months offering great value . Available for a minimum of 30 people the all inclusive packages includes your ceremony time and every thing you need for your celebration meal afterwards, including canapés, reception drinks, 3 course meal, toast wine and table flowers. We also offer special seasonal deals with the addition of a recommended Photographer. Please ask for details of the current offer Ideally located just off the A2 and within minutes of the M25. -

Traffic Schedule No. 2 Stop Intersections

TRAFFIC SCHEDULE NO. 2 STOP INTERSECTIONS Reference Section 11-2072 THIS SCHEDULE CONTAINS PAGES 2-1 THROUGH 2-118 ORDINANCES ADOPTED THROUGH #277 (9/28/2021) Traffic Schedule 2, Page 1 TRAFFIC SCHEDULE NO. 2 STOP INTERSECTIONS (Reference Section 11-2072 [c]) Aaron Drive at Keith Drive. #128, 2/9/93 Abbington Way at Laurel Glen Drive (both north & south approaches). #274, 8/14/07 Abbott Hall Drive at Cashlin Drive. #274, 8/14/07 Aberdeen Drive at Rose Lane. #513, 12/13/94 ACC Boulevard at Brier Creek Parkway (both eastbound and westbound approaches. #170, 2/27/07 ACC Boulevard at Mt. Herman Road. #15, 6/5/01 Accabonac Point at Poyner Road. #700, 2/23/10 Acer Court at Haymarket Lane. #753, 4/9/91 Acorn Street at Quail Drive. #886, 12/10/91 Acorn Street at Watkins Street. #886, 12/10/91 Adaba Drive at Ashe Avenue. #128, 2/9/93 Adams Street at Filmore Street. * Addison Place at Glascock Street. #886, 12/10/91 Adler Pass at Clyden Cove (both SE & NW Corners). #506, 12/9/08 Adler Pass at Neiman Cove. #506, 12/9/08 Advantis Drive at Grandover Drive. #70 9/4/01 Advantis Drive at Pearl Road. #70, 9/4/01 Agecroft Road at Chesterfield Road. * Agent Court at Tryon Pines Drive. #354, 6/30/98 Agnes Street at Nazareth Street. #847, 9/24/91 Agnes Street at Price Street. #78, 10/27/92 Airline Drive at Sandia Drive. #208 7/12/88 Alafia Court at Filbin Creek Drive. #730, 2/15/00 Alafia Court at Haines Creek Lane. -

Provisional Checklist and Account of the Mammals of the London Borough of Bexley

PROVISIONAL CHECKLIST AND ACCOUNT OF THE MAMMALS OF THE LONDON BOROUGH OF BEXLEY Compiled by Chris Rose BSc (Hons), MSc. 4th edition. December 2016. Photo: Donna Zimmer INTRODUCTION WHY PROVISIONAL? Bexley’s mammal fauna would appear to be little studied, at least in any systematic way, and its distribution is incompletely known. It would therefore be premature to suggest that this paper contains a definitive list of species and an accurate representation of their actual abundance and geographical range in the Borough. It is hoped, instead, that by publishing and then occasionally updating a ‘provisional list’ which pulls together as much currently available information as can readily be found, it will stimulate others to help start filling in the gaps, even in a casual way, by submitting records of whatever wild mammals they see in our area. For this reason the status of species not thought to currently occur, or which are no longer found in Bexley, is also given. Mammals are less easy to study than some other groups of species, often being small, nocturnal and thus inconspicuous. Detecting equipment is needed for the proper study of Bats. Training in the live-trapping of small mammals is recommended before embarking on such a course of action, and because Shrews are protected in this regard, a special licence should be obtained first in case any are caught. Suitable traps need to be purchased. Dissection of Owl pellets and the identification of field signs such as Water Vole droppings can help fill in some of the gaps. Perhaps this document will be picked up by local students who may be looking for a project to do as part of their coursework, and who will be able to overcome these obstacles. -

Bexley Growth Strategy

www.bexley.gov.uk Bexley Growth Strategy December 2017 Bexley Growth Strategy December 2017 Leader’s Foreword Following two years of detailed technical work and consultation, I am delighted to present the Bexley Growth Strategy that sets out how we plan to ensure our borough thrives and grows in a sustainable way. For centuries, Bexley riverside has been a place of enterprise and endeavour, from iron working and ship fitting to silk printing, quarrying and heavy engineering. People have come to live and work in the borough for generations, taking advantage of its riverside locations, bustling town and village centres and pleasant neighbourhoods as well as good links to London and Kent, major airports, the Channel rail tunnel and ports. Today Bexley remains a popular place to put down roots and for businesses to start and grow. We have a wealth of quality housing and employment land where large and small businesses alike are investing for the future. We also have a variety of historic buildings, neighbourhoods and open spaces that provide an important link to our proud heritage and are a rich resource. We have great schools and two world-class performing arts colleges plus exciting plans for a new Place and Making Institute in Thamesmead that will transform the skills training for everyone involved in literally building our future. History tells us that change is inevitable and we are ready to respond and adapt to meet new opportunities. London is facing unprecedented growth and Bexley needs to play its part in helping the capital continue to thrive. But we can only do that if we plan carefully and ensure we attract the right kind of quality investment supported by the funding of key infrastructure by central government, the Mayor of London and other public bodies.