Research Into Recent Dynamics of the Press Sector in the UK and Globally

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art

DIVIDED ART GALLERY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA WORLDS 2018 ADELAIDE BIENNIAL OF AUSTRALIAN ART The cat sits under the dark sky in the night, watching the mysterious trees. There are spirits afoot. She watches, alert to the breeze and soft movements of leaves. And although she doesn’t think of spirits, she does feel them. In fact, she is at one with them: possessed. She is a wild thing after all – a hunter, a killer, a ferocious lover. Our ancestors lived under that same sky, but they surely dreamed different dreams from us. Who knows what they dreamed? A curator’s dream DIVIDED WORLDS ART 2018 GALLERY ADELAIDE OF BIENNIAL SOUTH OF AUSTRALIA AUSTRALIAN ERICA GREEN ART ARTISTS LISA ADAMS JULIE GOUGH VERNON AH KEE LOUISE HEARMAN ROY ANANDA TIMOTHY HORN DANIEL BOYD KEN SISTERS KRISTIAN BURFORD LINDY LEE MARIA FERNANDA CARDOSO KHAI LIEW BARBARA CLEVELAND ANGELICA MESITI KIRSTEN COELHO PATRICIA PICCININI SEAN CORDEIRO + CLAIRE HEALY PIP + POP TAMARA DEAN PATRICK POUND TIM EDWARDS KHALED SABSABI EMILY FLOYD NIKE SAVVAS HAYDEN FOWLER CHRISTIAN THOMPSON AMOS GEBHARDT JOHN R WALKER GHOSTPATROL DAVID BOOTH DOUGLAS WATKIN pp. 2–3, still: Angelica Mesiti, born Kristian Burford, born 1974, Waikerie, 1976, Sydney Mother Tongue, 2017, South Australia, Audition, Scene 1: two-channel HD colour video, surround In Love, 2013, fibreglass reinforced sound, 17 minutes; Courtesy the artist polyurethane resin, polyurethane and Anna Schwartz Gallery Melbourne foam, oil paint, Mirrorpane glass, Commissioned by Aarhus European Steelcase cubicles, aluminium, steel, Capital of Culture 2017 in association carpet, 261 x 193 x 252 cm; with the 2018 Adelaide Biennial Courtesy the artist photo: Bonnie Elliott photo: Eric Minh Swenson DIRECTOR'S 7 FOREWORD Contemporary art offers a barometer of the nation’s Tim Edwards (SA), Emily Floyd (Vic.), Hayden Fowler (NSW), interests, anxieties and preoccupations. -

The Resurgent Role of the Independent Mortgage Bank

ONE VOICE. ONE VISION. ONE RESOURCE. IMB FACT SHEET The Resurgent Role of the Independent Mortgage Bank Independent mortgage banks (IMBs) are non-depository institutions that typically focus exclusively on mortgage lending. Mortgage bankers have originated and serviced loans since the 1870s, and independent mortgage bankers have been an important component of the mortgage market for more than a century. According to Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data, there were 838 independent mortgage bankers in 2016, with these lenders operating across all 50 states. Independent mortgage bankers are a diverse market segment, and can range in production volume from $10 million to almost $100 billion annually. Companies can have fewer than 100 employees or several thousand. The increasing importance of the independent mortgage banker strengthens the industry through the market diversity, competition and innovation that these firms can foster. THE FACTS ABOUT IMBs tested. Additionally, other entities, such as FHA, also provide oversight, establish minimum financial standards • Mortgage Banking Is a Time-Tested Business Model. and require regular financial reporting. The independent mortgage banking model has existed for more than 100 years, and provides important market • Independent Mortgage Bankers Support Communities, diversification. Consumers and the American Economy. There are more than 800 IMBs active in the market today, the vast • IMBs Have Skin in the Game. Most independent mortgage majority of which are locally owned institutions serving banks are private companies that are owned by a their communities by bringing mortgage funds from Wall single or small number of owners who are personally Street to Main Street. responsible for and financially tied to the success of the company. -

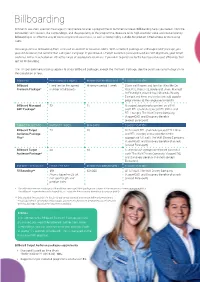

Billboarding Billboards Are Short Sponsor Messages (5 Sec) Before Or After a Programme Or Commercial Break

Billboarding Billboards are short sponsor messages (5 sec) before or after a programme or commercial break. Billboarding helps you benefit from the connection with viewers, the surroundings, and the popularity of the programme. Because of its high attention value and cost-efficiency, billboarding is an effective way of increasing brand awareness, as well as being highly suitable for product introductions or increasing sales. You can purchase billboarding from us based on content or based on GRPs. With a Content package or a Managed GRP package, you yourself decide on the content that suits your campaign. If you choose a Target Audience package based on GRP objectives, your target audience will be reached on an attractive range of appropriate channels. If you wish to purchase to the best-possible cost-efficiency, then opt for Fill boarding. The TV spot commercial policy applies to all our Billboard packages, except the Premium Package. See the purchase system diagram for the calculation of fees. CONTENT FEE/PRODUCT INDEX MINIMUM PERIOD/GRPS CLASSIFICATION Billboard Fixed fee for the agreed Minimum period 1 week Claim well-known and familiar titles like De Premium Package* number of billboards Klok, RTL Weer, RTL Boulevard, Jinek, Married At First Sight, Weet Ik Veel, Chantals Beauty Camper and films and series (we add popular programmes to the range every month) Billboard Managed 83 15 Managed according to content on all full GRP Package* audit RTL channels (except RTL Crime and RTL Lounge), The Walt Disney Company, ViacomCBS, and Discovery Benelux (except Eurosport). TARGET AUDIENCE PRODUCT INDEX MIN GRPS CLASSIFICATION Billboard Target 78 10 All full audit RTL channels (except RTL Crime Audience Package and RTL Lounge) and a selection of the Plus* appropriate full audit The Walt Disney Company, ViacomCBS, and Discovery Benelux channels (except Eurosport). -

COVID-19: Make It the Last Pandemic

COVID-19: Make it the Last Pandemic Disclaimer: The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city of area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Report Design: Michelle Hopgood, Toronto, Canada Icon Illustrator: Janet McLeod Wortel Maps: Taylor Blake COVID-19: Make it the Last Pandemic by The Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness & Response 2 of 86 Contents Preface 4 Abbreviations 6 1. Introduction 8 2. The devastating reality of the COVID-19 pandemic 10 3. The Panel’s call for immediate actions to stop the COVID-19 pandemic 12 4. What happened, what we’ve learned and what needs to change 15 4.1 Before the pandemic — the failure to take preparation seriously 15 4.2 A virus moving faster than the surveillance and alert system 21 4.2.1 The first reported cases 22 4.2.2 The declaration of a public health emergency of international concern 24 4.2.3 Two worlds at different speeds 26 4.3 Early responses lacked urgency and effectiveness 28 4.3.1 Successful countries were proactive, unsuccessful ones denied and delayed 31 4.3.2 The crisis in supplies 33 4.3.3 Lessons to be learnt from the early response 36 4.4 The failure to sustain the response in the face of the crisis 38 4.4.1 National health systems under enormous stress 38 4.4.2 Jobs at risk 38 4.4.3 Vaccine nationalism 41 5. -

Independent Panel Review of the Doing Business Report

Independent Panel Review of the Doing Business report June 2013 REPORT SIGNATORIES This report was compiled by the I ndependent Doing Business Report Review P anel, whose members append their signatures below. Trevor Manuel (Chairperson) Carlos Arruda Sergei Guriev Dr Jihad Azour Dr Huguette Labelle Jean -Pierre LANDAU Chong-en Bai Jean Pierre Landau Timothy Besley Arun Maira Dong-Sung Cho Hendrik Wolff 24 June 2013 Washington , D.C. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................... 1 The report’s role and reputation ........................................................................................... 3 Recommendations ................................................................................................................. 4 A. PURPOSE OF THE REVIEW .................................................................................................. 7 Review scope and timeline .................................................................................................... 7 Rationale of the Doing Business report ................................................................................. 7 The need for a review .......................................................................................................... 10 B. OVERVIEW OF THE DOING BUSINESS REPORT .................................................................... 13 Structure of the Doing Business report .............................................................................. -

Pressreader Newspaper Titles

PRESSREADER: UK & Irish newspaper titles www.edinburgh.gov.uk/pressreader NATIONAL NEWSPAPERS SCOTTISH NEWSPAPERS ENGLISH NEWSPAPERS inc… Daily Express (& Sunday Express) Airdrie & Coatbridge Advertiser Accrington Observer Daily Mail (& Mail on Sunday) Argyllshire Advertiser Aldershot News and Mail Daily Mirror (& Sunday Mirror) Ayrshire Post Birmingham Mail Daily Star (& Daily Star on Sunday) Blairgowrie Advertiser Bath Chronicles Daily Telegraph (& Sunday Telegraph) Campbelltown Courier Blackpool Gazette First News Dumfries & Galloway Standard Bristol Post iNewspaper East Kilbride News Crewe Chronicle Jewish Chronicle Edinburgh Evening News Evening Express Mann Jitt Weekly Galloway News Evening Telegraph Sunday Mail Hamilton Advertiser Evening Times Online Sunday People Paisley Daily Express Gloucestershire Echo Sunday Sun Perthshire Advertiser Halifax Courier The Guardian Rutherglen Reformer Huddersfield Daily Examiner The Independent (& Ind. on Sunday) Scotland on Sunday Kent Messenger Maidstone The Metro Scottish Daily Mail Kentish Express Ashford & District The Observer Scottish Daily Record Kentish Gazette Canterbury & Dist. IRISH & WELSH NEWSPAPERS inc.. Scottish Mail on Sunday Lancashire Evening Post London Bangor Mail Stirling Observer Liverpool Echo Belfast Telegraph Strathearn Herald Evening Standard Caernarfon Herald The Arran Banner Macclesfield Express Drogheda Independent The Courier & Advertiser (Angus & Mearns; Dundee; Northants Evening Telegraph Enniscorthy Guardian Perthshire; Fife editions) Ormskirk Advertiser Fingal -

Modern Newspaper Management and Press Laws

MODERN NEWSPAPER MANAGEMENT AND PRESS LAWS Syllabus Newspaper – Overview, Definitions, History, Gazettes and bulletins, Industrial Revolution Categories – Daily, Weekly and other, Geographical scope and distribution, Local or regional, National Subject matter – Technology: Print, Online, Formats Newspaper production process. News gathering - Pre press, Press: Lithographic stage, Impression stage, Post press Media & Press Laws Press, Law, Society & Democracy Constitutional Safeguards To Freedom Of Press Meaning Of Freedom Basis Of Democracy Role Of Journalism Role Of Journalism In Society The Power Of Press Press Commissions & Their Recommendations Press & Registration Of Books Act Press Council Working Journalist Act Law Of Libel & Defamation Official Secret Act Parliamentary Privileges Right To Information Copyright Act Social Responsibility Of Press & Freedom Of Expression MODERN NEWSPAPER MANAGEMENT AND PRESS LAWS Tutorial A newspaper is a periodical publication containing written information about current events. Newspapers can cover wide variety of fields such as politics, business, sport and art and often include materials such as opinion columns, weather forecasts, reviews of local services, obituaries, birth notices, crosswords, editorial cartoons, comic strips, and advice columns. Most newspapers are businesses, and they pay their expenses with a mixture of subscription revenue, newsstand sales, and advertising revenue. The journalism organizations that publish newspapers are themselves often metonymically called newspapers. Newspapers have traditionally been published in print (usually on cheap, low- grade paper called newsprint). However, today most newspapers are also published on websites as online newspapers, and some have even abandoned their print versions entirely. Newspapers developed in the 17th century, as information sheets for businessmen. By the early 19th century, many cities in Europe, as well as North and South America, published newspapers. -

Newspapers October 2009 Central Illinois Teaching with Primary Sources Newsletter

Newspapers October 2009 Central Illinois Teaching with Primary Sources Newsletter EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY EDWARDSVILLE CONTACTS We got the scoop: newspapers • Melissa Carr [email protected] Editor • Cindy Rich [email protected] • Amy Wilkinson [email protected] INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Topic Introduction 2 Connecting to Illinois 3 Learn More with 4 American Memory In the Classroom 6 Test Your Knowledge 7 Images Sources 9 www.eiu.edu/~eiutps/newsletter Page 2 Newspapers We got the scoop: Newspapers Welcome to the 24th issue of the Central Illinois of the Revolutionary War there were 37 independent Teaching with Primary Sources Newsletter a American newspapers. collaborative project of Teaching with Primary Sources In an attempt to deal with Great Britain's enormous Programs at Eastern Illinois University and Southern national debt, England passed the Stamp Act in 1765, Illinois University Edwardsville. Our goal is to bring you which taxed all paper documents. This tax included the topics that connect to the Illinois Learning Standards as American colonies since they were under British control. well as provide you with amazing items from the Library This was met with great resistance in the colonies. of Congress. The Industrial Revolution changed the newspaper Newspapers are mentioned specifically within ISBE industry. With the introduction of printing presses, materials for the following Illinois Learning Standards newspapers were able to print at a much faster pace and (found within goal, standard, benchmark or performance higher quantity. This meant that more pages could be descriptors) 1.A-Apply word analysis and vocabulary skills added to the newspapers so local news could be to comprehend selections. -

SA Public Sector Newsletter

ADVICE | TRANSACTIONS | DISPUTES 17 NOVEMBER 2020 ISSUE 37 PUBLIC SECTOR NEWSLETTER - SOUTH AUSTRALIA Welcome to Issue 37 of the SA Public Sector Newsletter. Cashless Centrelink payment cards “not worth the human cost” Crime Stoppers SA has received an $800,000 investment Cashless debit cards for welfare recipients are over four years from the Marshall Government, to help demeaning and create stress for recipients, senators improve the future safety of South Australians. The have been told as the Morrison Government looks ongoing funding will allow Crime Stoppers to expand its to widen the scheme. (06 November 2020) https:// operations across South Australia, including measures to indaily.com.au/news/2020/11/06/cashless-centrelink- stop rural criminal activity. payment-cards-not-worth-the-human-cost/ In other local news, the laws that will significantly reduce Clive Palmer has lost his WA border battle. What does it the discounts available to serious criminal offenders for mean for state and territory boundaries? early guilty pleas have now come into effect, with the previous available discount of up to 40% for an early guilty The High Court has knocked back billionaire miner Clive plea reduced to a maximum of 25%. Palmer’s challenge against Western Australia’s COVID-19 hard border closure. Chief Justice Susan Kiefel said the This issue of the Newsletter also provides the usual round- court had found the Act complied with the constitution up of practice notes, cases and legislation assistance. and the directions did not raise a constitutional -

Where Have All the Soldiers Gone?

Conflict Studies Research Centre Russi an Series 06/47 Defence Academy of the United Kingdom Where Have All the Soldiers Gone? Russia’s Military Plans Versus Demographic Reality Keir Giles Key Points * Russia intends to halve the term of conscription into the armed forces from two years to one in 2008, while retaining the overall size of the forces. * This implies doubling the number of conscripts drafted each year, but demographic change in Russia means there will not be enough healthy 18-year-olds to do this. * A number of grounds for deferral of conscription are to be abolished, but this will still not provide anything like enough conscripts. * Recruitment and retention on contract service appear insufficient to fill the gap. * The timing of the change-over to one-year conscription threatens major disruption and upheaval in the armed forces, at or around the time of the 2008 presidential election. BBC Monitoring Conflict Studies Research Centre www.monitor.bbc.co.uk www.defac.ac.uk/csrc Contents Not Enough Russians 1 Conscription Reform Deferrals Cut 4 Conscript Quality 5 Recruitment Centres 6 Manpower Planning Official Recognition 7 Official Statistics 7 Who is “Listed on the Military Register”? 10 Impact of Contract Service 11 Impact of Alternative Civilian Service 12 Impact of Cuts in Military Higher Education 12 Further Reform Conscript Age 13 Draft Rejects 14 Consequences Managing Transition 14 Implications for Training 15 Conclusion 16 06/47 Where Have All the Soldiers Gone? Russia’s Military Plans versus Demographic Reality Keir Giles Not Enough Russians Russia’s plans for maintaining the size of its armed forces largely by means of conscription, while at the same time halving the conscription term from two years to one, are at odds with the realities of demography. -

Media Contact List for Artists Contents

MEDIA CONTACT LIST FOR ARTISTS CONTENTS Welcome to the 2015 Adelaide Fringe media contacts list. 7 GOLDEN PUBLICITY TIPS 3 PRINT MEDIA 5 Here you will fi nd the information necessary to contact local, interstate and national media, of all PRINT MEDIA: STREET PRESS 9 types. This list has been compiled by the Adelaide NATIONAL PRINT MEDIA 11 Fringe publicity team in conjunction with many of our RADIO MEDIA 13 media partners. RADIO MEDIA: COMMUNITY 17 The booklet will cover print, broadcast and online media as well as local photographers. TELEVISION MEDIA 20 ONLINE MEDIA 21 Many of these media partners have offered generous discounts to Adelaide Fringe artists. PHOTOGRAPHERS 23 Please ensure that you identify yourself clearly as PUBLICISTS 23 an Adelaide Fringe artist if you purchase advertising ADELAIDE FRINGE MEDIA TEAM 24 space. Information listed in this guide is correct as at 20 November 2014. 2 GOLDEN PUBLICITY TIPS There are over 1000 events and exhibitions taking part in the 2015 Adelaide Fringe and while they all deserve media attention, it is essential that you know how to market your event effectively to journalists and make your show stand out. A vibrant pitch and easy-to-access information is the key to getting your share of the media love. Most time- poor journalists would prefer to receive an email containing a short pitch, press release, photo/s and video clip rather than a phone call – especially in the fi rst instance. Here are some tips from the Adelaide Fringe Publicity Team on how to sell your story to the media: 1) Ensure you upload a Media Kit to FERS (Step 3, File Upload) These appear on our web page that only journalists can see and the kits encourage them to fi nd out more about you and your show. -

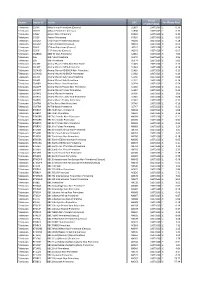

S1867 16071609 0

Period Domain Station ID Station UDC Per Minute Rate (YYMMYYMM) Television CSTHIT 4Music Non-Primetime (Census) S1867 16071609 £ 0.36 Television CSTHIT 4Music Primetime (Census) S1868 16071609 £ 0.72 Television C4SEV 4seven Non-Primetime F0029 16071608 £ 0.30 Television C4SEV 4seven Primetime F0030 16071608 £ 0.60 Television CS5USA 5 USA Non-Primetime (Census) H0010 16071608 £ 0.28 Television CS5USA 5 USA Primetime (Census) H0011 16071608 £ 0.56 Television CS5LIF 5* Non-Primetime (Census) H0012 16071608 £ 0.34 Television CS5LIF 5* Primetime (Census) H0013 16071608 £ 0.67 Television CSABNN ABN TV Non-Primetime S2013 16071608 £ 7.05 Television 106 alibi Non-Primetime S0373 16071608 £ 2.52 Television 106 alibi Primetime S0374 16071608 £ 5.03 Television CSEAPE Animal Planet EMEA Non-Primetime S1445 16071608 £ 0.10 Television CSEAPE Animal Planet EMEA Primetime S1444 16071608 £ 0.19 Television CSDAHD Animal Planet HD EMEA Non-Primetime S1483 16071608 £ 0.10 Television CSDAHD Animal Planet HD EMEA Primetime S1482 16071608 £ 0.19 Television CSEAPI Animal Planet Italy Non-Primetime S1530 16071608 £ 0.08 Television CSEAPI Animal Planet Italy Primetime S1531 16071608 £ 0.16 Television CSANPL Animal Planet Non-Primetime S0399 16071608 £ 0.54 Television CSDAPP Animal Planet Poland Non-Primetime S1556 16071608 £ 0.11 Television CSDAPP Animal Planet Poland Primetime S1557 16071608 £ 0.22 Television CSANPL Animal Planet Primetime S0400 16071608 £ 1.09 Television CSAPTU Animal Planet Turkey Non-Primetime S1946 16071608 £ 0.08 Television CSAPTU Animal