Track & Field News E Le Parole Dell'atletica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

— 2016 T&FN Men's U.S. Rankings —

50K WALK — 2016 T&FN Men’s U.S. Rankings — 1. John Nunn 2. Nick Christie 100 METERS 1500 METERS 110 HURDLES 3. Steve Washburn 1. Justin Gatlin 1. Matthew Centrowitz 1. Devon Allen 4. Mike Mannozzi 2. Trayvon Bromell 2. Ben Blankenship 2. David Oliver 5. Matthew Forgues 3. Marvin Bracy 3. Robby Andrews 3. Ronnie Ash 6. Ian Whatley 4. Mike Rodgers 4. Leo Manzano 4. Jeff Porter HIGH JUMP 5. Tyson Gay 5. Colby Alexander 5. Aries Merritt 1. Erik Kynard 6. Ameer Webb 6. Johnny Gregorek 6. Jarret Eaton 2. Kyle Landon 7. Christian Coleman 7. Kyle Merber 7. Jason Richardson 3. Deante Kemper 8. Jarrion Lawson 8. Clayton Murphy 8. Aleec Harris 4. Bradley Adkins 9. Dentarius Locke 9. Craig Engels 9. Spencer Adams 5. Trey McRae 10. Isiah Young 10. Izaic Yorks 10. Adarius Washington 6. Ricky Robertson 200 METERS STEEPLE 400 HURDLES 7. Dakarai Hightower 1. LaShawn Merritt 1. Evan Jager 1. Kerron Clement 8. Trey Culver 2. Justin Gatlin 2. Hillary Bor 2. Michael Tinsley 9. Bryan McBride 3. Ameer Webb 3. Donn Cabral 3. Byron Robinson 10. Randall Cunningham 4. Noah Lyles 4. Andy Bayer 4. Johnny Dutch POLE VAULT 5. Michael Norman 5. Mason Ferlic 5. Ricky Babineaux 1. Sam Kendricks 6. Tyson Gay 6. Cory Leslie 6. Jeshua Anderson 2. Cale Simmons 7. Sean McLean 7. Stanley Kebenei 7. Bershawn Jackson 3. Logan Cunningham 8. Kendal Williams 8. Donnie Cowart 8. Quincy Downing 4. Mark Hollis 9. Jarrion Lawson 9. Dan Huling 9. Eric Futch 5. Jake Blankenship 10. -

RESULTS 400 Metres Men - Final

Sopot (POL) World Indoor Championships 7-9 March 2014 RESULTS 400 Metres Men - Final RECORDS RESULT NAME COUNTRY AGE VENUE DATE World Indoor Record WIR 44.57 Kerron CLEMENT USA 20 Fayetteville, AR 12 Mar 2005 Championship Record CR 45.11 Nery BRENES CRC27 Istanbul 10 Mar 2012 World Leading WL 45.03 Deon LENDORE TTO 22 College Station, TX 1 Mar 2014 Area Indoor Record AIR National Indoor Record NIR Personal Best PB Season Best SB Final 8 March 2014 20:27 START TIME PLACE BIB NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH LANE RESULT REACTION Fn 1 156 Pavel MASLÁK CZE 21 Feb 91 5 45.24 NIR 0.179 2 112 Chris BROWN BAH 15 Oct 78 6 45.58 PB 0.244 3 390 Kyle CLEMONS USA 27 Aug 90 4 45.74 0.189 4 413 David VERBURG USA 14 May 91 1 46.21 0.218 5 370 Lalonde GORDON TTO 25 Nov 88 2 46.39 0.230 6 149 Nery BRENES CRC 25 Sep 85 3 47.32 0.158 ALL-TIME TOP LIST SEASON TOP LIST RESULT NAME VENUE DATE RESULT NAME VENUE DATE 44.57 Kerron CLEMENT (USA) Fayetteville, AR 12 Mar 05 45.03 Deon LENDORE (TTO) College Station, TX 1 Mar 14 44.63 Michael JOHNSON (USA) Atlanta, GA 4 Mar 95 45.17 Lalonde GORDON (TTO) Boston (BU), MA 8 Feb 14 44.80 Kirani JAMES (GRN) Fayetteville, AR 27 Feb 11 45.24 Pavel MASLÁK (CZE) Sopot 8 Mar 14 44.93 LaShawn MERRITT (USA) Fayetteville, AR 11 Feb 05 45.28 Arman HALL (USA) College Station, TX 1 Mar 14 45.02 Danny EVERETT (USA) Stuttgart 2 Feb 92 45.39 Vernon NORWOOD (USA) College Station, TX 1 Mar 14 45.03 Torrin LAWRENCE (USA) Fayetteville, AR 12 Feb 10 45.58 Chris BROWN (BAH) Sopot 8 Mar 14 45.03 Deon LENDORE (TTO) College Station, TX 1 Mar 14 45.60 Kyle CLEMONS (USA) Albuquerque 23 Feb 14 45.05 Thomas SCHÖNLEBE (GDR) Sindelfingen 5 Feb 88 45.62 David VERBURG (USA) Albuquerque 23 Feb 14 45.05 Alvin HARRISON (USA) Atlanta, GA 28 Feb 98 45.71 Nigel LEVINE (GBR) Birmingham (NIA), GBR 15 Feb 14 45.11 Nery BRENES (CRC) Istanbul 10 Mar 12 45.84 Kind BUTLER III (USA) Albuquerque 23 Feb 14 Timing and Measurement by SEIKO Data Processing by CANON AT-400-M-f--1--.RS1..v1 Issued at 20:33 on Saturday, 08 March 2014 Official IAAF Partners. -

IMPRESSIONEN IMPRESSIONS Bmw-Berlin-Marathon.Com

IMPRESSIONEN IMPRESSIONS bmw-berlin-marathon.com 2:01:39 DIE ZUKUNFT IST JETZT. DER BMW i3s. BMW i3s (94 Ah) mit reinem Elektroantrieb BMW eDrive: Stromverbrauch in kWh/100 km (kombiniert): 14,3; CO2-Emissionen in g/km (kombiniert): 0; Kraftstoffverbrauch in l/100 km (kombiniert): 0. Die offi ziellen Angaben zu Kraftstoffverbrauch, CO2-Emissionen und Stromverbrauch wurden nach dem vorgeschriebenen Messverfahren VO (EU) 715/2007 in der jeweils geltenden Fassung ermittelt. Bei Freude am Fahren diesem Fahrzeug können für die Bemessung von Steuern und anderen fahrzeugbezogenen Abgaben, die (auch) auf den CO2-Ausstoß abstellen, andere als die hier angegebenen Werte gelten. Abbildung zeigt Sonderausstattungen. 7617 BMW i3s Sportmarketing AZ 420x297 Ergebnisheft 20180916.indd Alle Seiten 18.07.18 15:37 DIE ZUKUNFT IST JETZT. DER BMW i3s. BMW i3s (94 Ah) mit reinem Elektroantrieb BMW eDrive: Stromverbrauch in kWh/100 km (kombiniert): 14,3; CO2-Emissionen in g/km (kombiniert): 0; Kraftstoffverbrauch in l/100 km (kombiniert): 0. Die offi ziellen Angaben zu Kraftstoffverbrauch, CO2-Emissionen und Stromverbrauch wurden nach dem vorgeschriebenen Messverfahren VO (EU) 715/2007 in der jeweils geltenden Fassung ermittelt. Bei Freude am Fahren diesem Fahrzeug können für die Bemessung von Steuern und anderen fahrzeugbezogenen Abgaben, die (auch) auf den CO2-Ausstoß abstellen, andere als die hier angegebenen Werte gelten. Abbildung zeigt Sonderausstattungen. 7617 BMW i3s Sportmarketing AZ 420x297 Ergebnisheft 20180916.indd Alle Seiten 18.07.18 15:37 AOK Nordost. Beim Sport dabei. Nutzen Sie Ihre individuellen Vorteile: Bis zu 385 Euro für Fitness, Sport und Vorsorge. Bis zu 150 Euro für eine sportmedizinische Untersuchung. -

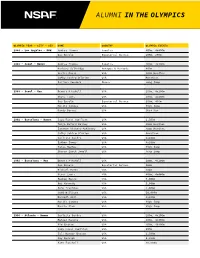

Alumni in the Olympics

ALUMNI IN THE OLYMPICS OLYMPIC YEAR - CITY - SEX NAME COUNTRY OLYMPIC EVENTS 1984 - Los Angeles - M&W Andrea Thomas Jamaica 400m, 4x400m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 100m, 200m 1988 - Seoul - Women Andrea Thomas Jamaica 400m, 4x400m Barbara Selkridge Antigua & Barbuda 400m Leslie Maxie USA 400m Hurdles Cathy Schiro O'Brien USA Marathon Juliana Yendork Ghana Long Jump 1988 - Seoul - Men Dennis Mitchell USA 100m, 4x100m Steve Lewis USA 400m, 4x400m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 200m, 400m Hollis Conway USA High Jump Randy Barnes USA Shot Put 1992 - Barcelona - Women Suzy Favor Hamilton USA 1,500m Tonja Buford Bailey USA 400m Hurdles Janeene Vickers-McKinney USA 400m Hurdles Cathy Schiro O'Brien USA Marathon Carlette Guidry USA 4x100m Esther Jones USA 4x100m Tanya Hughes USA High Jump Sharon Couch-Jewell USA Long Jump 1992 - Barcelona - Men Dennis Mitchell USA 100m, 4x100m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 100m Michael Bates USA 200m Steve Lewis USA 400m, 4x400m Reuben Reina USA 5,000m Bob Kennedy USA 5,000m John Trautman USA 5,000m Todd Williams USA 10,000m Darnell Hall USA 4x400m Hollis Conway USA High Jump Darrin Plab USA High Jump 1996 - Atlanta - Women Carlette Guidry USA 200m, 4x100m Maicel Malone USA 400m, 4x400m Kim Graham USA 400m, 4X400m Suzy Favor Hamilton USA 800m Juli Henner Benson USA 1,500m Amy Rudolph USA 5,000m Kate Fonshell USA 10,000m ALUMNI IN THE OLYMPICS OLYMPIC YEAR - CITY - SEX NAME COUNTRY OLYMPIC EVENTS Ann-Marie Letko USA Marathon Tonja Buford Bailey USA 400m Hurdles Janeen Vickers-McKinney USA 400m Hurdles Shana Williams -

Teen Sensation Athing Mu

• ALL THE BEST IN RUNNING, JUMPING & THROWING • www.trackandfieldnews.com MAY 2021 The U.S. Outdoor Season Explodes Athing Mu Sets Collegiate 800 Record American Records For DeAnna Price & Keturah Orji T&FN Interview: Shalane Flanagan Special Focus: U.S. Women’s 5000 Scene Hayward Field Finally Makes Its Debut NCAA Formchart Faves: Teen LSU Men, USC Women Sensation Athing Mu Track & Field News The Bible Of The Sport Since 1948 AA WorldWorld Founded by Bert & Cordner Nelson E. GARRY HILL — Editor JANET VITU — Publisher EDITORIAL STAFF Sieg Lindstrom ................. Managing Editor Jeff Hollobaugh ................. Associate Editor BUSINESS STAFF Ed Fox ............................ Publisher Emeritus Wallace Dere ........................Office Manager Teresa Tam ..................................Art Director WORLD RANKINGS COMPILERS Jonathan Berenbom, Richard Hymans, Dave Johnson, Nejat Kök SENIOR EDITORS Bob Bowman (Walking), Roy Conrad (Special AwaitsAwaits You.You. Projects), Bob Hersh (Eastern), Mike Kennedy (HS Girls), Glen McMicken (Lists), Walt Murphy T&FN has operated popular sports tours since 1952 and has (Relays), Jim Rorick (Stats), Jack Shepard (HS Boys) taken more than 22,000 fans to 60 countries on five continents. U.S. CORRESPONDENTS Join us for one (or more) of these great upcoming trips. John Auka, Bob Bettwy, Bret Bloomquist, Tom Casacky, Gene Cherry, Keith Conning, Cheryl Davis, Elliott Denman, Peter Diamond, Charles Fleishman, John Gillespie, Rich Gonzalez, Ed Gordon, Ben Hall, Sean Hartnett, Mike Hubbard, ■ 2022 The U.S. Nationals/World Champion- ■ World Track2023 & Field Championships, Dave Hunter, Tom Jennings, Roger Jennings, Tom ship Trials. Dates and site to be determined, Budapest, Hungary. The 19th edition of the Jordan, Kim Koffman, Don Kopriva, Dan Lilot, but probably Eugene in late June. -

2009 IAAF World Champs

Men Did not compete (29) AG Kruger Morningside Sheldon Sheldon Ashton Eaton Oregon Mountain View Bend Brad Walker Washington University Spokane Casey Malone Colorado State Arvada West Arvada Christian Cantwell Missouri Eldon Eldon Darvis Patton TCU Lake Highlands Dallas David Payne Cincinnati Wyoming Wyoming Derek Miles South Dakota Bella Vista Fair Oaks George Kitchens Clemson Glenn Hills Augusta Ian Waltz Washington State Post Falls Post Falls Jake Arnold Arizona Maria Carrillo Santa Rosa James Jenkins Arkansas State Mc Cluer North Florissant Joshua Mc Adams BYU Broadview Heights Broadview Heights Lionel Larry USC Dominquez Compton Michael Rodgers Oklahoma Baptist Berkeley St. Louis Mike Hazle Texas State Temple Temple Nick Symmonds Willamette Bishop Kelly Boise Shawn Crawford Clemson Indian Land Indian Land Brandon Roulhac Albany State (GA) Marianna Marianna Chris Hill Georgia Sulphur Sulphur Daniel Huling Miami (O) Geneva Geneva Dorian Ulrey Arkansas Riverdale Port Byron Jarred Rome Boise State Marysville-Pilchuck Marysville Jeremy Scott Arkansas Norfolk Norfolk Khadevis Robinson TCU Trimble Tech Fort Worth Monzavous Edwards Texas Tech Opelika Opelika Ryan Brown Washington Renton Renton Tim Nelson Wisconsin Liberty Christian Palo Cedro Tora Harris Princeton South Atlanta Atlanta Men Did compete (32) Tyson Gay Arkansas Lafayette Lexington Matt Tegenkamp Wisconsin Lees Summit Lees Summit Sean Furey Dartmouth Methuen Methuen Keith Moffatt Morehouse Menchville Newport News Kerron Clement Florida La Porte La Porte Jeremy Wariner Baylor -

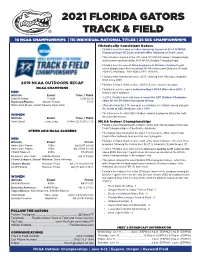

2021 Florida Gators Track & Field

2021 FLORIDA GATORS TRACK & FIELD 10 NCAA CHAMPIONSHIPS | 115 INDIVIDUAL NATIONAL TITLES | 28 SEC CHAMPIONSHIPS Historically Consistent Gators • Florida’s men have won or taken runner-up honors at 23 of 34 NCAA Championships (67.6 percent) with Mike Holloway as head coach. • That includes victories at the 2018 and 2019 NCAA Indoor Championships, and a runner-up finish at the 2018 NCAA Outdoor Championships. • Florida’s men are one of three programs in Division I history to post seven straight top-3 finishes at both NCAA Indoors and Outdoors (Florida, 2009-15; Arkansas, 1992-2000; UTEP, 1975-82). • Florida’s men finished second in 2019, claiming their 10th top-2 outdoors finish since 2009. 2019 NCAA OUTDOORS RECAP • Florida’s 10 top-2 finishes since 2009 is tied the most in that span. NCAA CHAMPIONS • Florida’s men have won a nation-leading 9 NCAA titles since 2010 - 5 MEN indoors and 4 outdoors Athlete Event Time / Mark Grant Holloway 110mH 12.98 [+0.8] • In 2018, Florida’s men and women swept the SEC Outdoor Champion- Raymond Ekevwo, 4x100m Relays 37.97 ships for the first time in program history. Hakim Sani Brown, Grant Holloway, Ryan Clark • Although it was the 11th sweep in meet history, the Gators’ sweep was just the fourth at SEC Outdoors since 1991. WOMEN • The titles were the sixth SEC Outdoor crowns in program history for both Athlete Event Time / Mark the men and women. Yanis David Long Jump 6.84m (22-5.25) [+1.5] NCAA Indoor Championships • Florida’s men finished fourth in March at the 2021 NCAA Indoor Track and Field Championships in Fayetteville, Arkansas. -

START LIST 400 Metres Men - Final

Sopot (POL) World Indoor Championships 7-9 March 2014 START LIST 400 Metres Men - Final RECORDS RESULT NAME COUNTRY AGE VENUE DATE World Indoor Record WIR 44.57 Kerron CLEMENT USA 20 Fayetteville, AR 12 Mar 2005 Championship Record CR 45.11 Nery BRENES CRC 27 Istanbul 10 Mar 2012 World Leading WL 45.03 Deon LENDORE TTO 22 College Station, TX 1 Mar 2014 o = Outdoor performance Final 8 March 2014 20:30 START TIME LANE BIB NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH PERSONAL BEST SEASON BEST 1 413 David VERBURG USA 14 May 91 45.62 45.62 2 370 Lalonde GORDON TTO 25 Nov 88 45.17 45.17 3 149 Nery BRENES CRC 25 Sep 85 45.11 46.25 4 390 Kyle CLEMONS USA 27 Aug 90 45.60 45.60 5 156 Pavel MASLÁK CZE 21 Feb 91 45.66 45.66 6 112 Chris BROWN BAH 15 Oct 78 45.78 45.84 ALL-TIME TOP LIST SEASON TOP LIST RESULT NAME VENUE DATE RESULT NAME VENUE DATE 44.57 Kerron CLEMENT (USA) Fayetteville, AR 12 Mar 05 45.03 Deon LENDORE (TTO) College Station, TX 1 Mar 14 44.63 Michael JOHNSON (USA) Atlanta, GA 4 Mar 95 45.17 Lalonde GORDON (TTO) Boston (BU), MA 8 Feb 14 44.80 Kirani JAMES (GRN) Fayetteville, AR 27 Feb 11 45.28 Arman HALL (USA) College Station, TX 1 Mar 14 44.93 LaShawn MERRITT (USA) Fayetteville, AR 11 Feb 05 45.39 Vernon NORWOOD (USA) College Station, TX 1 Mar 14 45.02 Danny EVERETT (USA) Stuttgart 2 Feb 92 45.60 Kyle CLEMONS (USA) Albuquerque 23 Feb 14 45.03 Torrin LAWRENCE (USA) Fayetteville, AR 12 Feb 10 45.62 David VERBURG (USA) Albuquerque 23 Feb 14 45.03 Deon LENDORE (TTO) College Station, TX 1 Mar 14 45.66 Pavel MASLÁK (CZE) Stockholm (Globe Arena) 6 Feb 14 45.05 Thomas SCHÖNLEBE (GDR) Sindelfingen 5 Feb 88 45.71 Nigel LEVINE (GBR) Birmingham (NIA), GBR 15 Feb 14 45.05 Alvin HARRISON (USA) Atlanta, GA 28 Feb 98 45.84 Kind BUTLER III (USA) Albuquerque 23 Feb 14 45.11 Nery BRENES (CRC) Istanbul 10 Mar 12 45.84 Chris BROWN (BAH) Sopot 7 Mar 14 Timing and Measurement by SEIKO Data Processing by CANON AT-400-M-f----.SL2..v1 Issued at 22:20 on Friday, 07 March 2014 Official IAAF Partners. -

This Is Your Invitation to Compete with the Best Athletes in the United States

This is your invitation to compete with the best Athletes in the United States 443rd Annual Great Southwest Track & Field ClassicClassic May 31, - June 1, 2-2018 UNM Track & Fieldld SSttadium, Allbuquerque,, NMNM wwwwww.greatsouthwestclassic.com.greatsouthwestclassic.com Former Great Southwest Track & Field Classic Athletes that have competed in the Olympics/NFL: Robert Griffin III-Quarterback, Jamaal Charles - Running Adrian Peterson - Running Jordon Roos, Offensive Washington Redskins Back, Kansas City Chiefs Back Minnesota Vikings Center-Seattle Seahawks Alexis Weeks Anicka Newell Ariana Washington Arman Hall Bianca Knight Boris Berian Bradley Adkins Brittany Borman Christian Taylor Courtney Okolo Devon Allen Emma Coburn Gil Roberts Inika McPherson Jarrin Solomon Jason Richardson Jennifer Madu Kerron Clement Keturah Orji Leonel Manzano Logan Cunningham Marquis Dendy Mason Finley Michelle Carter Ryan Bailey Shawn Barber Shelbi Vaughan Tiffany Lott-Hogan Trayvon Bromell William Clay PHOTO CREDITS: USTFA/USOC photos - Jill Greer; Robert Grifffiin III - Geoff Burke - USA TODAY Sports; Jamaal Charles - Peter G. Aiken/Getty Images ; Jennifer Madu - Evans Caglage/Dallas News; Anicka Newell, Shawn Barber - Canadian Olympic Team. 43rd Annual Great Southwest Track & Field Classic May 31, June 1, 2-2018 UNM Track & Field Stadium, Albuquerque, New Mexico A National Scholastic Athletics Foundation Select Meet Congratulations! You have been invited to the 43rd Annual Great Southwest Track & Field Classic, where you will compete with best athletes in the United States! Having been recognized as one of the top track and field athletes in the United States, it’s my pleasure to extend this invitation to you, to compete in the 43rd Annual Great Southwest Track & Field Classic at the University of New Mexico Track & Field Stadium, in Albuquerque, New Mexico. -

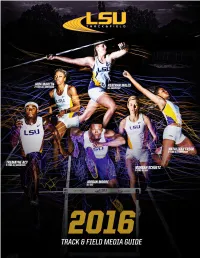

2016 Lsu Track & Field Media Guide

Outlook LSU 2016 LSU TRACK & FIELD MEDIA GUIDE Only One LSU 52 LSU Administration Review 53 Director of Athletics Records 4 Campus Life 110 2015 Men’s Indoor Performance List 146 Men’s All-Time Indoor Records 5 Why LSU? 111 2015 Women’s Indoor Performance List 147 Women’s All-Time Indoor Records 6 LSU Track & Field: An Era of Excellence Preview 112 2015 Men’s Outdoor Performance List 148 Men’s All-Time Outdoor Records 9 All-Time Results 54 2016 Men’s Season Preview 113 2015 Women’s Outdoor Performance List 149 Women’s All-Time Outdoor Records 10 Dominance on the Track 56 2016 Women’s Season Preview 114 2015 Cross Country Rosters 150 Men’s All-Time Relay Records 12 The Winning Streak 58 2016 Men’s Track & Field Roster 115 2015 Cross Country Results 151 Women’s All-Time Relay Records 13 History of the 4x100-Meter Relay 59 2016 Women’s Track & Field Roster 116 2015 Accolades 152 Men’s Indoor Record Book 14 The X-Man 153 Women’s Indoor Record Book 16 The Bowerman Award 154 Men’s Outdoor Record Book 18 Games of the XXX Olympiad Coaches History 155 Women’s Outdoor Record Book 60 Dennis Shaver, Head Coach 20 Games of the XXIX Olympiad 117 LSU Olympians 156 Multi-Event Record Book 63 Debbie Parris-Thymes, Assistant Coach 22 LSU Olympic Medalists 118 World-Class Tigers 157 Cross Country Record Book 64 Todd Lane, Assistant Coach 24 Wall of Champions 120 NCAA Champions 158 Tiger Letterwinners 65 Derek Yush, Assistant Coach 26 LSU Athletics Hall of Fame 125 SEC Champions 160 Lady Tiger Letterwinners 28 Track Stars on the Gridiron 66 Bennie Brazell, -

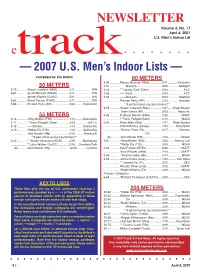

NEWSLETTER Volume 6, No

NEWSLETTER Volume 6, No. 17 April 4, 2007 U.S. Men’s Indoor List etrack — 2007 U.S. Men’s Indoor Lists — compiled by Jim Rorick 60 METERS 6.46 ............ Marcus Brunson (Nike) ............... 2/11 ............Karlsruhe 50 METERS 6.51 ............ ——Brunson ............................... 2/03 .............Stuttgart 5.79 ............ Shane Crawford (InHS) .............. 3/11 ..................... NIN 6.52 ............ ***Jacoby Ford (Clem) ................ 2/24 ...................ACC 5.81 ............ Justin Murdock (MdHS) .............. 3/11 ..................... NIN 6.53 ............ ——Ford ..................................... 2/24 ...................ACC .................... Jeremy Rankin (CoHS) .............. 3/11 ..................... NIN 6.54 ............ ——Brunson ............................... 2/03 .............Stuttgart 5.82 ............ Rynell Parson (TxHS) ................. 3/11 ..................... NIN .................... Preston Perry (API) .................... 2/10 .............Houston 5.83 ............ Preston Perry (API) .................... 2/04 ......... Saskatoon **6 performances by 3 performers** 6.55 ............ Shawn Crawford (Nike) .............. 1/27 ......Reeb Boston .................... -Demi Omole (Wi) ....................... 2/03 ............Meyo Inv 55 METERS 6.56 ............ DaBryan Blanton (Nike) .............. 2/25 ...............USATF 6.14 ............ -Greg Bolden (FlSt) .................... 1/13 .........Gainesville .................... **Travis Padgett (Clem) .............. 3/10 .................NCAA -

P 001 – F Front Inside & P001

186 DAEGU 2011 ★ PAST RESULTS/WORLD CHAMPS WOMENʼS 100m WOMEN 4, Diane Williams USA 11.07 0.240 5, Aneliya Nuneva BUL 11.09 0.169 100 Metres Helsinki 1983 6, Angela Bailey CAN 11.18 0.191 7, Pam Marshall USA 11.19 0.242 Final (Aug 8) (-0.5) Angella Issajenko CAN DQ (11.09) 0.203 1, Marlies Göhr GDR 10.97 The semi-finals indicated that the GDR were likely to repeat their 2, Marita Koch GDR 11.02 Helsinki success. Gladisch won the first race in a windy 10.82, while 3, Diane Williams USA 11.06 the other went to Drechsler in a legal championship record of 10.95. 4, Merlene Ottey JAM 11.19 The standard was fierce, with clockings of 11.07w and 11.15 insuffi- 5, Angela Bailey CAN 11.20 cient for a place in the final. Defending Champion Göhr was among the 6, Helinä Marjamaa FIN 11.24 non-qualifiers. 7, Angella Taylor CAN 11.30 Following the exploits of Ben Johnson in the men’s 100m final 20 Evelyn Ashford USA DNF minutes earlier, there were hopes of a record in the women’s race. One of the most eagerly awaited women’s clashes in Helsinki ended These were blighted by a change in direction of the wind. shockingly when Evelyn Ashford tore her right hamstring halfway Gladisch dominated the final from start to finish. At halfway she through the final. led with 6.07 from Nuneva (6.10), Ottey and Issajenko (both 6.12). At Both Marlies Göhr (10.81) and Ashford (10.79) had set world this point Drechsler – who was clearly last out of the blocks – was sixth records in 1983, so it was a surprise to see them drawn together in the (6.18), but she produced the best finish to claim the silver.