Someone Like You by Sarah Dessen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Sarah Dessen Is Synonmyous with Contemporary YA Fiction.” —Entertainment Weekly

SARAH DESSEN “Sarah Dessen is synonmyous with contemporary YA fiction.” —Entertainment Weekly ABOUT THE BOOK: Peyton, Sydney’s charismatic older brother, has always been the star of the family, receiving the lion’s share of their parents’ attention and—lately— concern. When Peyton’s increasingly reckless behavior culminates in an accident, a drunk driving conviction, and a jail sentence, Sydney is cast adrift, searching for her place in the family and the world. When everyone else is so worried about Peyton, is she the only one concerned about the victim of the accident? Enter the Chathams, a warm, chaotic family who run a pizza parlor, play bluegrass on weekends, and pitch in to care for their mother, who has multiple sclerosis. Here Sydney experiences unquestioning acceptance. And here she meets Mac, gentle, watchful, and protective, who makes Sydney feel seen, really seen, for the first time. The uber-popular Sarah Dessen explores her signature COMING MAY 2015 themes of family, self-discovery, and change in her twelfth novel, sure to delight her legions of fans. PRAISE FOR SAINT ANYTHING H “Once again, Dessen demonstrates her tremendous skill in evoking powerful emotions through careful, quiet prose, while delivering a satis- fying romance.” —Publisher’s Weekly, starred review “A rich emotional landscape . A many-layered story told with a light touch.” —Kirkus ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Sarah Dessen grew up in Chapel Hill, North Carolina and attended UNC- Chapel Hill, graduating with highest honors in Creative Writing. She is the author of several novels, including Someone Like You and Just Listen. A motion picture based on her first two books, entitled How to Deal, was released in 2003. -

This Lullaby by Sarah Dessen CHAPTER ONE the Name of The

This Lullaby by Sarah Dessen CHAPTER ONE The name of the song is “This Lullaby.” At this point, I’ve probably heard it, oh, about a million times. Approximately. All my life I’ve been told about how my father wrote it the day I was born. He was on the road somewhere in Texas, already split from my mom. The story goes that he got word of my birth, sat down with his guitar, and just came up with it, right there in a room at a Motel 6. An hour of his time, just a few chords, two verses and a chorus. He’d been writing music all his life, but in the end it would be the only song he was known for. Even in death, my father was a one-hit wonder. Or two, I guess, if you count me. Now, the song was playing overhead as I sat in a plastic chair at the car dealership, in the first week of June. It was warm, everything was blooming, and summer was practically here. Which meant, of course, that it was time for my mother to get married again. This was her fourth time, fifth if you include my father. I chose not to. But they were, in her eyes, married—if being united in the middle of the desert by someone they’d met at a rest stop only moments before counts as married. It does to my mother. But then, she takes on husbands the way other people change their hair color: out of boredom, listlessness, or just feeling that this next one will fix everything, once and for all. -

Clearview Regional High School District Summer Assignment Coversheet 2017

Clearview Regional High School District Summer Assignment Coversheet 2017 Course English III- Advanced and Honors Teacher(s) Ms. Satterfield, Mr. Porter, & Ms. Barry Due Date Monday, September 11, 2017 Grade Category/Weight for Q1 Collected and counts as a Daily Assignment on 9/11. After opportunity for class discussion or questions, counts as a Minor Assessment/Quiz Grade on 9/15 New Jersey Student Learning ● Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support Standards covered analysis of what the text says. ● Determine two or more themes or central ideas of a text and analyze their development over the course of the text, including how they work together and build on one another. ● By the end of grade 11, read and comprehend literature, including stories, dramas, and poems, in the grades 11-CCR text complexity band proficiently, with scaffolding as needed at the high end of the range. Description of Assignment 1) Students are to read a book of their choice and analyze the text for the following literary approaches: Gender Studies, Biographical, Historical, Psychoanalytical, Marxist, Formalist, Reader Response 2) Complete graphic organizer at the end of this document 3) Choose the responses from two boxes in the organizer and develop your ideas into a paragraph that analyzes the novel as a whole. Explain why your points are significant to the text and society as a whole. Purpose of Assignment Analyze literature through various critical perspectives Specific Expectations Thoroughly and independently complete graphic organizer with comments that demonstrate analysis. Then develop ideas into a well constructed paragraph to analyze the novel as a whole. -

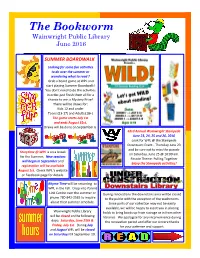

The Bookworm Wainwright Public Library June 2016

The Bookworm Wainwright Public Library June 2016 SUMMER BOARDWALK Looking for some fun activities to do over the summer or wondering what to read ? Grab a board game at WPL and start playing Summer Boardwalk! You don’t need to do the activities in order-just finish them all for a chance to win a Mystery Prize! There will be draws for: Kids 12 and under Teens (13-17) and Adults (18+) The game starts July 1st and ends August 31st. Draws will be done on September 6. 63rd Annual Wainwright Stampede June 23, 24, 25 and 26, 2016 Look for WPL @ the Stampede Downtown Event - Thursday June 23 and be sure not to miss the parade Storytime @ WPLis on a break on Saturday, June 25 @ 10:00 am. for the Summer. New sessions Parade Theme: Pulling Together will begin in September and Enjoy the Stampede activities! registration will be available August 1st. Check WPL’s website or Facebook page for details. Rhyme Time will be returning to WPL in the Fall. Drop into Parent Link Centre over the summer or During renovations the downstairs area will be closed phone 780-842-2585 to inquire to the public with the exception of the washrooms. about their summer schedule. Since parts of our collection may not be easily available, we will be happy to assist you in placing Wainwright Public Library holds to bring books up from storage or in from other will be closed on the following libraries. We apologize for any inconvenience during days: Saturday, June 25th & the renovation period and offer our sincere thanks Friday, July 1st. -

The Sarah Dessen Book Club Kit

THE SARAH DESSEN BOOK CLUB KIT SPEND YOUR SUMMER WITH SARAH Dear Book Club Coordinator: Here at Penguin Young Readers Group we are calling Summer 2013 The Summer of Sarah. The beloved bestseller Sarah Dessen will be publishing her 11th book this summer, which takes place in one of her fans’ favorite settings, the fi ctional beach town of Colby. Dessen’s latest novel, The Moon and More, will be hitting the shelves this June, and she will be touring in schools and bookstores all across the country to connect with her fans new and old. In anticipation of a local visit, or in lieu of meeting the author in person, we have assembled your Summer of Sarah book club kit to welcome readers in your community into your local book club meetings all summer long. With Penguin's Summer of Sarah book club kit, you can hold discussions about specifi c Dessen titles or more thematic sessions on a variety of topics, such as relationships, moving away, loss and letting go, and change (which everyone can relate to). Since the summer is time for teens to let go of the worries and stress of the school “ year, this book club kit also includes fun quizzes, a recipe from Sarah's favorite summer treats, and playlists handpicked by Sarah herself. Tailor your book club in whatever format best fi ts your participants, and have a fun-fi lled summer… with Sarah! 1 stick margarine Tips for your event: 1.5 graham cracker crumbs 1 small bag chocolate chips 14 oz. -

NPR's Your Favorites: 100 Best-Ever Teen Novels

NPR’s Your Favorites: 100 Best-Ever Teen Novels Popularity Title Read it 1 Harry Potter Series by J. K. Rowling The adventures of Harry Potter, the Boy Who Lived, and his wand-wielding friends at the Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. Harry, Ron and Hermione must master their craft and battle the machinations of the evil wizard Voldemort and his Death Eaters. 2 The Hunger Games Series by Suzanne Collins In the ruins of a future North America, a young girl is picked to leave her impoverished district and travel to the decadent Capitol for a battle to the death in the savage Hunger Games. But for Katniss Everdeen, winning the Games only puts her deeper in danger as the strict social order of Panem begins to unravel. 3 To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee This Pulitzer Prize-winning novel from author Harper Lee explores racial tensions in the fictional "tired old town" of Maycomb, Ala., through the eyes of 6- year-old Scout Finch. As her lawyer father, Atticus, defends a black man accused of rape, Scout and her friends learn about the unjust treatment of African-Americans — and their mysterious neighbor, Boo Radley. 4 The Fault In Our Stars by John Green Despite the tumor-shrinking medical miracle that has bought her a few more years, Hazel has never been anything but terminal, her final chapter inscribed upon diagnosis. But when a gorgeous plot twist named Augustus Waters suddenly appears at the Cancer Kid Support Group, Hazel's story is about to be completely rewritten 5 The Hobbit by J.R.R. -

Sarah Dessen

Discussion Questions for What’s so great about Sarah Dessen? • Do you think Auden’s mother is threatened by her Read them all! Along for the Ride daughter’s choice to spend the summer with her father and his new family? What does her mother • Why is it so difficult for Auden to feel like a “normal” fear will happen? teenager? • How does Auden’s relationship with her step • In what ways are Hollis’ and Auden’s childhoods mother, Heidi, change? What does Auden discover different? How has this affected them as they have about Heidi throughout the course of the story? matured and made important decisions about their • Explain the significance of the picture frame lives? Hollis sends home to Auden; why does the • Auden and her new sister, Thisbe, are named after inscription, “The Best of Times” bother her so literary influences in her father’s life. Why are much? How does this gift serve as a catalyst for • $19.99 HC: 978-0-670-01194-0 names so important to Auden’s dad, Robert? What change in Auden’s plans? does he believe the right name will do for his chil- • Why does Auden feel she needs to stay with dren? How does the baby’s name cause a conflict her dad and Heidi after their baby is born? between Auden’s dad and Heidi? What does the What does she hope to gain from her visit? result of their disagreement indicate about their HC: 978-0-670-01088-2 • $18.99 HC: 978-0-670-06105-1 • $18.99 relationship? • Auden’s first encounter with Eli comes when she PB: 978-0-14-241472-9 • $8.99 PB: 978-0-14-241097-4 • $8.99 is taking her baby sister for a stroll in hopes of • Auden’s mom tells her, “People don’t change. -

Just Listening to Sarah Dessen

Robyn Seglem Just Listening to Sarah Dessen t was the second week of school, reception and at the conference, and I had just brought my copy where she spoke about romance Iof Sarah Dessen’s Just Listen to and YA literature. As expected, my classroom to put on my she was easy to talk to, and shelves. As we waited for first hour shared insights into her career as to begin, Callie, a bright-eyed 7th an author: grader, rushed toward me, explain ing that she had just seen the list of TAR: I first discovered your work recommended books in my class when I was teaching sopho room newsletter and had noticed more English in 2000. When the newest Sarah Dessen title. Did I my librarian recommended have it? Reaching for it on my Dreamland to me, I immedi shelves, I shared with her that I not ately read it and fell in love only had the book, but I would with Caitlin’s story. My have the privilege of interviewing and meeting Sarah students quickly began passing it around, and I’m in Nashville at the ALAN convention. From that not sure it ever went back on the library’s shelves moment, Callie and I shared a bond that went beyond that year. Then, a couple years ago, I switched to the student-teacher bond: it was a bond shared by seventh grade English, and figured I would have to avid readers. discover new authors that would appeal to a August, September, October and, finally, Novem younger audience. -

S20-US-Kids-Feb-27.Pdf

HARPERFESTIVAL The Adventures of Paddington: Meet Paddington Summary Paddington is coming to Nickelodeon in an all-new animated series in Winter 2020. This tabbed board book will introduce preschoolers to all of the colorful and fun characters from the animated series. Also Available The Adventures of Paddington: Paddington and the Monster Hunt - Sticker Book - 7/21/2020 $5.99 9780062983107 HarperFestival The Adventures of Paddington: Pancake Day! - Paperback - 5/5/2020 $5.99 9780062983039 9780062983091 The Adventures of Paddington: Pancake Day! - Hardcover - 5/5/2020 $21.00 9780062983046 Pub Date: 5/5/20 The Adventures of Paddington: Paddington and the Painting - Paperback - 5/5/2020 $5.99 9780062983060 On Sale Date: 5/5/20 The Adventures of Paddington: Paddington and the Painting - Hardcover - 5/5/2020 $21.00 9780062983077 Ship Date: 4/8/20 Ebooks $10.99 CAD The Adventures of Paddington: Paddington and the Monster Hunt - E-Book - 7/21/2020 $4.99 9780062983114 Board Book The Adventures of Paddington: Pancake Day! - E-Book - 5/5/2020 $4.99 9780062983053 The Adventures of Paddington: Paddington and the Painting - E-Book - 5/5/2020 $4.99 9780062983084 18 Pages Carton Qty: 80 Print Run: 75K Ages 0 to 4, Grades Grade P Juvenile Fiction / Media Tie-In JUV027000 Series: The Adventures of Paddington 7 in H | 7 in W | 1.4 lb Wt A Parade of Elephants Board Book Kevin Henkes Summary Up and down, over and under, through and around . five big and brightly colored elephants are on a mission in this board book for young children. Where are they going? What will they do when they get to the end of their journey? It’s a surprise! Greenwillow Books With a text shimmering with repetition and rhythm, bright pastel illustrations, large and readable type, and an 9780062668295 adorable parade of elephants, Kevin Henkes introduces basic concepts such as numbers, shapes, adjectives, Pub Date: 5/5/20 adverbs, and daytime and nighttime. -

Top 100 Best Books for Young Adults

Top 100 Best Books for Young Adults Book Author 1. Harry Potter (series) J.K. Rowling 2. The Hunger Games (series) Suzanne Collins 3. To Kill a Mockingbird Harper Lee 4. The Fault in Our Stars John Green 5. The Hobbit J.R.R Tolkien 6. The Catcher in the Rye J.D. Salinger 7. The Lord of the Rings (series) J.R.R. Tolkien 8. Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury 9. Looking for Alaska John Green 10. The Book Thief Markus Zusak 11. The Giver (series) Lois Lowry 12. The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (series) Douglas Adams 13. The Outsiders S.E. Hinton 14. Anne of Green Gables (series) Lucy Maud Montgomery 15. His Dark Materials (series) Philip Pullman 16. The Perks of Being a Wallflower Stephen Chbosky 17. The Princess Bride William Goldman 18. Lord of the Flies William Golding 19. Divergent (series) Veronica Roth 20. Paper Towns John Green 21. The Mortal Instruments (series) Cassandra Clare 22. An Abundance of Katherines John Green 23. Flowers for Algernon Daniel Keyes 24. Thirteen Reasons Why Jay Asher 25. The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time Mark Haddon 26. Speak Laurie Halse Anderson 27. Twilight (series) Stephenie Meyer 28. Uglies (series) Scott Westerfeld 29. The Infernal Devices (series) Cassandra Clare 30. Tuck Everlasting Natalie Babbitt 31. The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian Sherman Alexie 32. The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants (series) Ann Brashares 33. The Call of the Wild Jack London 34. Will Grayson, Will Grayson John Green, David Levithan 35. Go Ask Alice Anonymous 36. -

DREAMLAND by Sarah Dessen a Reader's Companion by Patty Campbell Well-Known Columnist and Lecturer on Young Adult Literature

DREAMLAND by Sarah Dessen A Reader's Companion By Patty Campbell Well-known Columnist and Lecturer on Young Adult Literature Introduction "When he hit me, I didn't see it coming, It was just a quick blur, a flash out of the corner of my eye, and then the side of my face just exploded, burning, as his hands slammed against me." Strange, sleepy Rogerson, with his long brown dreads and brilliant green eyes, had seemed to Caitlin to be an open door. With him she could be anybody, not just the second-rate shadow of her two-years-older sister Cass. But now she is drowning in the vacuum Cass left behind when she turned her back on her family's expectations. Caitlin wanders in a dreamland of drugs and a nightmare of sudden fists, trapped in her search for herself. As violence becomes more and more prevalent in our world, one out of every five teenage girls in America will be beaten by a dating partner, and one third to one half of married women will be victims of abuse. Yet shame, fear, and assumed guilt keeps many in conspiracy of silence about this widespread but invisible anguish. Why do girls allow themselves to get into such relationships—and what keeps them there? In this riveting novel, Sarah Dessen searches for understanding and answers through the mind of a young girl who suddenly finds herself in a trap of constant menace, a trap that is baited with love and need. More and more she must frantically manage her every action to avoid being hit by the hands that had seemed so gentle. -

Burnham 1 Paige Burnham English 4995 Nancy West 13 May 2011

Burnham 1 Paige Burnham English 4995 Nancy West 13 May 2011 Young Adult Novels and Their Film Adaptations When novels first originated in the mid eighteenth century, they were seen as lowbrow and unworthy of serious study. Now, the study of novels is a staple to academia, but certain types of novels are still considered with critical disdain, and young adult literature is among them. This disdain is perhaps due to the fact that as a genre, young adult fiction is fairly new: although authors like Judy Blume and S.E. Hinton were writing literature aimed at high school students in the 1970s, it was not until recently that the genre has been officially recognized as distinct from children’s literature. In the past fifteen years, both bookstores and public libraries have created young adult sections. It also seems that with every passing year, these sections get larger and larger. In fact, young adult literature is one of the few areas of print books in which sales are rising. However, the genre of young adult literature is still seen as “an entrée into more sophisticated reading for its intended audience,” and not “a viable area of academic study in and of itself” (Coats 317). The themes and content of young adult novels are just as worthy of consideration as those in children’s novels, which are often studied critically. Furthermore, young adult novels should be studied for the sheer effect that they have on teens and adults alike. During the teenage years, one is still trying to figure out one’s views and beliefs, and young adult books may shape whom these teens turn out to be.