Courts of Heaven Music from the Eton Choirbook Volume 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St. John the Evangelist Roman Catholic Church. Center Moriches

St.September John 29, 2019 the Evangelist Roman Catholic Church 25 Ocean Avenue, Center Moriches, New York 11934 -3698 631-878-0009 | [email protected]| Parish Website: www.sjecm.org Facebook: Welcome Home-St. John the Evangelist Twitter: @StJohnCM PASTORAL TEAM Instagram|Snapchat: @sjecm Reverend John Sureau Pastor “Thus says the LORD the God [email protected] (ext. 105) of hosts: Woe to the Reverend Felix Akpabio Parochial Vicar complacent in Zion!” [email protected] (ext. 108) Reverend Michael Plona Amos 6:1 Parochial Vicar [email protected] (ext. 103) John Pettorino Deacon [email protected] 26th Sunday in Ordinary Time Sr. Ann Berendes, IHM September 29, 2019 Director of Senior Ministry [email protected] (ext. 127) Alex Finta Come to the quiet! Come and know God’s healing of Director of Parish Social Ministry The church building is open from 6:30 [email protected] (ext. 119) the sick! a.m. to approximately 7 p.m., if not later, Please contact the Rectory (631.878.0009) Andrew McKeon each night. Seton Chapel, in the white Director of Music Ministries for a priest to celebrate the Sacrament of [email protected] convent building, is open around 8 a.m. the Anointing of the Sick with the Michelle Pirraglia and also remains open to approximately 7 seriously ill or those preparing for p.m. Take some time to open your heart surgery. Please also let us know if a loved Director of Faith Formation to the voice of God. [email protected] (ext. 123) one is sick so we can pray for them at Come and pray with us! Katie Waller Mass and list their name in the bulletin. -

View/Download Concert Program

Christmas in Medieval England Saturday, December 19, 2009 at 8 pm First Church in Cambridge, Congregational Christmas in Medieval England Saturday, December 19, 2009 at 8 pm First Church in Cambridge, Congregational I. Advent Veni, veni, Emanuel | ac & men hymn, 13th-century French? II. Annunciation Angelus ad virginem | dt bpe 13th-century monophonic song, Arundel MS / text by Philippe the Chancellor? (d. 1236) Gabriel fram Heven-King | pd ss bpe Cotton fragments (14th century) Gaude virgo salutata / Gaude virgo singularis isorhythmic motet for Annunciation John Dunstaple (d. 1453) Hayl, Mary, ful of grace Trinity roll (early 15th century) Gloria (Old Hall MS, no. 21) | jm ms ss gb pg Leonel Power (d. 1445) Ther is no rose of swych vertu | dt mb pg bpe Trinity roll Ibo michi ad montem mirre | gp jm ms Power III. Christmas Eve Veni redemptor gencium hymn for first Vespers of the Nativity on Christmas Eve, Sarum plainchant text by St Ambrose (c. 340-97) intermission IV. Christmas Dominus dixit ad me Introit for the Mass at Cock-Crow on Christmas Day, Sarum plainchant Nowel: Owt of your slepe aryse | dt pd gp Selden MS (15th century) Gloria (Old Hall MS, no. 27) | mn gp pd / jm ss / mb ms Blue Heron Pycard (?fl. 1410-20) Pamela Dellal | pd ss mb bpe Ecce, quod natura Martin Near Selden MS Gerrod Pagenkopf Missa Veterem hominem: Sanctus Daniela Tošić anonymous English, c. 1440 Ave rex angelorum | mn mb ac Michael Barrett Egerton MS (15th century) Allen Combs Jason McStoots Missa Veterem hominem: Agnus dei Steven Soph Nowel syng we bothe al and som Mark Sprinkle Trinity roll Glenn Billingsley Paul Guttry Barbara Poeschl-Edrich, Gothic harp Scott Metcalfe,director Pre-concert talk by Daniel Donoghue, Professor of English, Harvard University sponsored by the Cambridge Society for Early Music Blue Heron Renaissance Choir, Inc. -

Conducting Studies Conference 2016

Conducting Studies Conference 2016 24th – 26th June St Anne’s College University of Oxford Conducting Studies Conference 2016 24-26 June, St Anne’s College WELCOME It is with great pleasure that we welcome you to St Anne’s College and the Oxford Conducting Institute Conducting Studies Conference 2016. The conference brings together 44 speakers from around the globe presenting on a wide range of topics demonstrating the rich and multifaceted realm of conducting studies. The practice of conducting has significant impact on music-making across a wide variety of ensembles and musical contexts. While professional organizations and educational institutions have worked to develop the field through conducting masterclasses and conferences focused on professional development, and academic researchers have sought to explicate various aspects of conducting through focussed studies, there has yet to be a space where this knowledge has been brought together and explored as a cohesive topic. The OCI Conducting Studies Conference aims to redress this by bringing together practitioners and researchers into productive dialogue, promoting practice as research and raising awareness of the state of research in the field of conducting studies. We hope that this conference will provide a fruitful exchange of ideas and serve as a lightning rod for the further development of conducting studies research. The OCI Conducting Studies Conference Committee, Cayenna Ponchione-Bailey Dr John Traill Dr Benjamin Loeb Dr Anthony Gritten University of Oxford University of -

A Prayer of Wonder ~ Our Lady Chapel

14th Week in Ordinary Time Volume XIX No. 31 July 5-6, 2014 CLOSING PRAYER: ~ A Prayer of Wonder ~ Our Lady Chapel O God, Maker of worlds and parent of the living, we turn to you because there is nowhere else to go. Our wisdom does not hold us and all our strength is weakness in the end. O Lord who made us and sent prophets and Jesus to teach us, help us to hear, to understand that in your word there is life. We seek to offer you praise. let us again give thanks that a prophet has been among us, that a word of healing and of power has been spoken, and we heard. The Spirit still enters into us and sets us on our feet. In the gift of God, in the power from on high, Our Lady Chapel is a Roman Catholic community founded in the love of let us live. Amen. the Father, centered in Christ, and rooted in the Holy Cross tenets of building family and embracing diversity. We are united in our journey CAMPUS MINISTRY OFFICE: of faith through prayer and sacrament, and we seek growth through The Campus Ministry Office is located in Our Lady Chapel. the wisdom of the Holy Spirit in liturgy and outreach, while responding phone: [440] 473-3560. e-mail: [email protected] to the needs of humanity. 20 14th Week in Ordinary Time July 5-6, 2014 CHAPEL PICNIC — NEXT SUNDAY: PRAYER REQUESTS: Next Sunday, July 13th is the date for our annual Chapel outdoor picnic. -

Gabriel Jackson

Gabriel Jackson Sacred choral WorkS choir of St Mary’s cathedral, edinburgh Matthew owens Gabriel Jackson choir of St Mary’s cathedral, edinburgh Sacred choral WorkS Matthew owens Edinburgh Mass 5 O Sacrum Convivium [6:35] 1 Kyrie [2:55] 6 Creator of the Stars of Night [4:16] Katy Thomson treble 2 Gloria [4:56] Katy Thomson treble 7 Ane Sang of the Birth of Christ [4:13] Katy Thomson treble 3 Sanctus & Benedictus [2:20] Lewis Main & Katy Thomson trebles (Sanctus) 8 A Prayer of King Henry VI [2:54] Robert Colquhoun & Andrew Stones altos (Sanctus) 9 Preces [1:11] Simon Rendell alto (Benedictus) The Revd Canon Peter Allen precentor 4 Agnus Dei [4:24] 10 Psalm 112: Laudate Pueri [9:49] 11 Magnificat (Truro Service) [4:16] Oliver Boyd treble 12 Nunc Dimittis (Truro Service) [2:16] Ben Carter bass 13 Responses [5:32] The Revd Canon Peter Allen precentor 14 Salve Regina [5:41] Katy Thomson treble 15 Dismissal [0:28] The Revd Canon Peter Allen precentor 16 St Asaph Toccata [8:34] Total playing time [70:22] Recorded in the presence Producer: Paul Baxter All first recordings Michael Bonaventure organ (tracks 10 & 16) of the composer on 23-24 Engineers: David Strudwick, (except O Sacrum Convivium) February and 1-2 March 2004 Andrew Malkin Susan Hamilton soprano (track 10) (choir), 21 December 2004 (St Assistant Engineers: Edward Cover image: Peter Newman, The Choir of St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Asaph Toccata) and 4 January Bremner, Benjamin Mills Vapour Trails (oil on canvas) 2005 (Laudate Pueri) in St 24-Bit digital editing: Session Photography: -

Saint Helen's Anglican Church

SAINT HELEN’S ANGLICAN CHURCH Founded 1911 This document is the continuation of a tradition of the gift of ministry by the Saint Helen’s Altar Guild. It is offered to the Glory of God, in gratitude for Altar Guild members – past, present and future, and particularly the Parish of Saint Helen’s. May we be given the grace to continue the work begun in our first century and to do the works of love that build community into the future. “This is our heritage, this that our fore bearers bequeathed us. Ours in our time, but in trust for the ages to be. A building so holy, His people most precious Faith and awe filled, possessors and stewards are we.” OUR EARLY HISTORY Because the High Altar is the focal point of St. Helen’s Church was built in 1911 during worship, Mr. Walker decided it should be a real estate boom and was consecrated by made from something special. He sent to the the Right Reverend A. J. de Pencier in Holy Land for some Cypress wood from the November of 1911. He was at that time the Mount of Olives and built the main altar and Archbishop of British Columbia. Much of the Lady Chapel altar. the surrounding land had already been subdivided and everyone thought that the Most altars have some form of adornment to area was destined to become the remind worshippers that it represents the metropolis of the Fraser Valley. It is a table of the Last Supper. Many churches had magnificent site and when the land was an antependium or Altar frontal made of originally logged off, it had an embroidered silk. -

Musica Britannica

T69 (2021) MUSICA BRITANNICA A NATIONAL COLLECTION OF MUSIC Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens c.1750 Stainer & Bell Ltd, Victoria House, 23 Gruneisen Road, London N3 ILS England Telephone : +44 (0) 20 8343 3303 email: [email protected] www.stainer.co.uk MUSICA BRITANNICA A NATIONAL COLLECTION OF MUSIC Musica Britannica, founded in 1951 as a national record of the British contribution to music, is today recognised as one of the world’s outstanding library collections, with an unrivalled range and authority making it an indispensable resource both for performers and scholars. This catalogue provides a full listing of volumes with a brief description of contents. Full lists of contents can be obtained by quoting the CON or ASK sheet number given. Where performing material is shown as available for rental full details are given in our Rental Catalogue (T66) which may be obtained by contacting our Hire Library Manager. This catalogue is also available online at www.stainer.co.uk. Many of the Chamber Music volumes have performing parts available separately and you will find these listed in the section at the end of this catalogue. This section also lists other offprints and popular performing editions available for sale. If you do not see what you require listed in this section we can also offer authorised photocopies of any individual items published in the series through our ‘Made- to-Order’ service. Our Archive Department will be pleased to help with enquiries and requests. In addition, choirs now have the opportunity to purchase individual choral titles from selected volumes of the series as Adobe Acrobat PDF files via the Stainer & Bell website. -

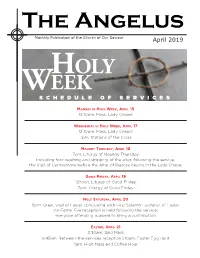

April 2019 Holy Week S C H E D U L E O F S E R V I C E S

The Angelus Monthly Publication of the Church of Our Saviour JanuaryApril 2019 HOLY WEEK SCHEDULE OF SERVICES MONDAY IN HOLY WEEK, APRIL 15 12:10pm, Mass, Lady Chapel WEDNESDAY IN HOLY WEEK, APRIL 17 12:10pm, Mass, Lady Chapel 7pm, Stations of the Cross MAUNDY THURSDAY, APRIL 18 7pm, Liturgy of Maundy Thursday Including foot washing and stripping of the altar; following the service, the Vigil of Gethsemane before the Altar of Repose begins in the Lady Chapel GOOD FRIDAY, APRIL 19 12noon, Liturgy of Good Friday 7pm, Liturgy of Good Friday HOLY SATURDAY, APRIL 20 8pm, Great Vigil of Easter concluding with First Solemn Eucharist of Easter An Easter Eve reception is held following the service; everyone attending is asked to bring a contribution EASTER, APRIL 21 8:30am, Said Mass 9:45am, Between-the-services reception | 10am, Easter Egg Hunt 11am, High Mass and Coffee Hour Events and Feast Days Events and Feast Days Parish Clean-Up Passiontide April 6, 2019 436-4522Begins or [email protected]. April 7, 2019 We’re in need of readers, actors, costume/set designers, On Saturday, April 6, 2019, from 9:00 am choristers,The last instrumentalists, two weeks before snack Easter, chefs, called and gen- until 1:00 pm, we will be holding a Spring clean- Passiontide,eral assistants, are aso transitional there’s definitely time, part something of Lent for up morning dedicated to getting the parish ready andeveryone! yet not aWe part’ll of have Lent. one During rehearsal Passiontide immediately for the upcoming Easter celebrations. Please plan theprior focus to ofthe Lent service, moves at 4:00from pm an (snacksexamination included). -

Sacred Music and Female Exemplarity in Late Medieval Britain

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Iconography of Queenship: Sacred Music and Female Exemplarity in Late Medieval Britain A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology by Gillian Lucinda Gower 2016 © Copyright by Gillian Lucinda Gower 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Iconography of Queenship: Sacred Music and Female Exemplarity in Late Medieval Britain by Gillian Lucinda Gower Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Elizabeth Randell Upton, Chair This dissertation investigates the relational, representative, and most importantly, constitutive functions of sacred music composed on behalf of and at the behest of British queen- consorts during the later Middle Ages. I argue that the sequences, conductus, and motets discussed herein were composed with the express purpose of constituting and reifying normative gender roles for medieval queen-consorts. Although not every paraliturgical work in the English ii repertory may be classified as such, I argue that those works that feature female exemplars— model women who exemplified the traits, behaviors, and beliefs desired by the medieval Christian hegemony—should be reassessed in light of their historical and cultural moments. These liminal works, neither liturgical nor secular in tone, operate similarly to visual icons in order to create vivid images of exemplary women saints or Biblical figures to which queen- consorts were both implicitly as well as explicitly compared. The Iconography of Queenship is organized into four chapters, each of which examines an occasional musical work and seeks to situate it within its own unique historical moment. In addition, each chapter poses a specific historiographical problem and seeks to answer it through an analysis of the occasional work. -

572840 Bk Eton EU

Music from THE ETON CHOIRBOOK LAMBE • STRATFORD • DAVY BROWNE • KELLYK • WYLKYNSON TONUS PEREGRINUS Music from the Eton Choirbook Out of the 25 composers The original index lists more represented in the Eton than 60 antiphons – all votive The Eton Choirbook – a giant the Roses’, and the religious reforms and counter-reforms Choirbook, several had strong antiphons designed for daily manuscript from Eton College of Henry VIII and his children. That turbulence devastated links with Eton College itself: extraliturgical use and fulfilling Chapel – is one of the greatest many libraries (including the Chapel Royal library) and Walter Lambe and, quite Mary’s prophecy that “From surviving glories of pre- makes the surviving 126 of the original 224 leaves in Eton possibly, John Browne were henceforth all generations shall Reformation England. There is a College Manuscript 178 all the more precious, for it is just there in the late 1460s as boys. call me blessed”; one of the proverb contemporary with the one of a few representatives of several generations of John Browne, composer of the best known – and justifiably so Eton Choirbook which might English music in a period of rapid and impressive astounding six-part setting of – is Walter Lambe’s setting of have been directly inspired by development. Eton’s chapel library itself had survived a Stabat mater dolorosa 5 may have gone on to New Nesciens mater 1 in which the composer weaves some the spectacular sounds locked forced removal in 1465 to Edward IV’s St George’s College, Oxford, while Richard Davy was at Magdalen of the loveliest polyphony around the plainchant tenor up in its colourful pages: “Galli cantant, Italiae capriant, Chapel – a stone’s throw away in Windsor – during a College, Oxford in the 1490s. -

Renaissance Terms

Renaissance Terms Cantus firmus: ("Fixed song") The process of using a pre-existing tune as the structural basis for a new polyphonic composition. Choralis Constantinus: A collection of over 350 polyphonic motets (using Gregorian chant as the cantus firmus) written by the German composer Heinrich Isaac and his pupil Ludwig Senfl. Contenance angloise: ("The English sound") A term for the style or quality of music that writers on the continent associated with the works of John Dunstable (mostly triadic harmony, which sounded quite different than late Medieval music). Counterpoint: Combining two or more independent melodies to make an intricate polyphonic texture. Fauxbourdon: A musical texture prevalent in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, produced by three voices in mostly parallel motion first-inversion triads. Only two of the three voices were notated (the chant/cantus firmus, and a voice a sixth below); the third voice was "realized" by a singer a 4th below the chant. Glogauer Liederbuch: This German part-book from the 1470s is a collection of 3-part instrumental arrangements of popular French songs (chanson). Homophonic: A polyphonic musical texture in which all the voices move together in note-for-note chordal fashion, and when there is a text it is rendered at the same time in all voices. Imitation: A polyphonic musical texture in which a melodic idea is freely or strictly echoed by successive voices. A section of freer echoing in this manner if often referred to as a "point of imitation"; Strict imitation is called "canon." Musica Reservata: This term applies to High/Late Renaissance composers who "suited the music to the meaning of the words, expressing the power of each affection." Musica Transalpina: ("Music across the Alps") A printed anthology of Italian popular music translated into English and published in England in 1588. -

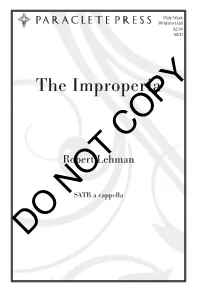

The Improperia I Did Raise Thee on High with Great Power

10 Holy Week paraclete press PPM01916M U $2.90 # # œ M/D & # ## œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ œ ˙. œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ ˙. œ w where- in have I wear- ied thee? Test--- i fy a gainst me. œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ ˙ U ? # # œ œ œ œœ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œœ œ œ ˙ œ œ ww # ## œ Cantor #### & # œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ The Improperia I did raise thee on high with great power: #### & # œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ and thou hast hang-- ed me up on the gib- bet of the Cross. Full Choir p COPY # # œ # ## ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙˙ œœ œ œ œ ˙. œ œ œ . & ˙ ˙ ˙ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙. œ O my peo- ple, what have I done un- to thee? or Robert Lehman œ ˙ ˙ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙. œ ? # # ˙ ˙ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ # ## œ œ œ ˙. œ NOTSATB a cappella # # œ U & # ## œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ œ ˙. œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ ˙. œ w where- in have I wear- ied thee? Test--- i fy a gainst me. œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ ˙ U ? # # œ œ œ œœ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œœ œ œ ˙ œ œ ww DO # ## œ PPM01916M 9 Cantor #### & # œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ I did smite the kings of the Can-- aan ites for thy sake: # ## & # # œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ andœ thou hast smit- ten my head with a reed.