Conservation Advice Liopholis Kintorei Great Desert Skink

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Answers to Questions on Notice Environment Portfolio

Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Answers to questions on notice Environment portfolio Question No: 3 Hearing: Additional Estimates Outcome: Outcome 1 Programme: Biodiversity Conservation Division (BCD) Topic: Threatened Species Commissioner Hansard Page: N/A Question Date: 24 February 2016 Question Type: Written Senator Waters asked: The department has noted that more than $131 million has been committed to projects in support of threatened species – identifying 273 Green Army Projects, 88 20 Million Trees projects, 92 Landcare Grants (http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/3be28db4-0b66-4aef-9991- 2a2f83d4ab22/files/tsc-report-dec2015.pdf) 1. Can the department provide an itemised list of these projects, including title, location, description and amount funded? Answer: Please refer to below table for itemised lists of projects addressing threatened species outcomes, including title, location, description and amount funded. INFORMATION ON PROJECTS WITH THREATENED SPECIES OUTCOMES The following projects were identified by the funding applicant as having threatened species outcomes and were assessed against the criteria for the respective programme round. Funding is for a broad range of activities, not only threatened species conservation activities. Figures provided for the Green Army are approximate and are calculated on the 2015-16 indexed figure of $176,732. Some of the funding is provided in partnership with State & Territory Governments. Additional projects may be approved under the Natinoal Environmental Science programme and the Nest to Ocean turtle Protection Programme up to the value of the programme allocation These project lists reflect projects and funding originally approved. Not all projects will proceed to completion. -

Their Botany, Essential Oils and Uses 6.86 MB

MELALEUCAS THEIR BOTANY, ESSENTIAL OILS AND USES Joseph J. Brophy, Lyndley A. Craven and John C. Doran MELALEUCAS THEIR BOTANY, ESSENTIAL OILS AND USES Joseph J. Brophy School of Chemistry, University of New South Wales Lyndley A. Craven Australian National Herbarium, CSIRO Plant Industry John C. Doran Australian Tree Seed Centre, CSIRO Plant Industry 2013 The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) was established in June 1982 by an Act of the Australian Parliament. ACIAR operates as part of Australia's international development cooperation program, with a mission to achieve more productive and sustainable agricultural systems, for the benefit of developing countries and Australia. It commissions collaborative research between Australian and developing-country researchers in areas where Australia has special research competence. It also administers Australia's contribution to the International Agricultural Research Centres. Where trade names are used this constitutes neither endorsement of nor discrimination against any product by ACIAR. ACIAR MONOGRAPH SERIES This series contains the results of original research supported by ACIAR, or material deemed relevant to ACIAR’s research and development objectives. The series is distributed internationally, with an emphasis on developing countries. © Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) 2013 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from ACIAR, GPO Box 1571, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia, [email protected] Brophy J.J., Craven L.A. and Doran J.C. 2013. Melaleucas: their botany, essential oils and uses. ACIAR Monograph No. 156. Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research: Canberra. -

Morphology and Burrowing Energetics of Semi-Fossorial Skinks (Liopholis Spp.) Nicholas C

© 2015. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | The Journal of Experimental Biology (2015) 218, 2416-2426 doi:10.1242/jeb.113803 RESEARCH ARTICLE Morphology and burrowing energetics of semi-fossorial skinks (Liopholis spp.) Nicholas C. Wu1,*, Lesley A. Alton1, Christofer J. Clemente1, Michael R. Kearney2 and Craig R. White1 ABSTRACT mouse (Notomys alexis), can expend 5000 times more energy −1 −1 Burrowing is an important form of locomotion in reptiles, but no study burrowing than running (7.1 kJ m compared with 1.2 J m ; has examined the energetic cost of burrowing for reptiles. This is White et al., 2006b). Despite the considerable energetic cost, significant because burrowing is the most energetically expensive burrowing has many benefits. These include food storage, access to mode of locomotion undertaken by animals and many burrowing underground food, a secure micro-environment free from predators species therefore show specialisations for their subterranean lifestyle. and extreme environmental gradients (Robinson and Seely, 1980), We examined the effect of temperature and substrate characteristics nesting (Seymour and Ackerman, 1980), hibernation (Moberly, (coarse sand or fine sand) on the net energetic cost of burrowing 1963) and enhanced acoustics to facilitate communication (Bennet- (NCOB) and burrowing rate in two species of the Egernia group of Clark, 1987). skinks (Liopholis striata and Liopholis inornata) compared with other Animals utilise a range of methods to burrow through soil, burrowing animals. We further tested for morphological specialisations depending on soil characteristics (density, particle size and moisture among burrowing species by comparing the relationship between content) and body morphology (limbed or limbless). -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

Robe River Limited 1.3

Clearing Permit Decision Report 1. Application details 1.1. Permit application details Permit application No.: 8319/1 Permit type: Purpose Permit 1.2. Proponent details Proponent’s name: Robe River Limited 1.3. Property details Property: Iron Ore (Robe River) Agreement Act 1964, Mineral Lease 248SA (AML 70/248) Local Government Area: Shire of Ashburton Colloquial name: Puluru 1.4. Application Clearing Area (ha) No. Trees Method of Clearing For the purpose of: 110 Mechanical Removal Mineral Exploration, Hydrogeological Investigations and Associated Activities. 1.5. Decision on application Decision on Permit Application: Grant Decision Date: 18 April 2019 2. Site Information 2.1. Existing environment and information 2.1.1. Description of the native vegetation under application Vegetation Description The vegetation of the application area is broadly mapped as Beard vegetation association 82: Hummock grassland, low tree steppe; Snappy Gum (Eucalyptus leucophloia) over Triodia wiseana (GIS Database). A flora and vegetation survey was conducted over the application area by Biota Environmental Services during July 2018. The following vegetation units were recorded within the application area (Biota, 2018): Vegetation of River Systems and Drainages R1: EcEvMaAtrCYPvCYa Eucalyptus camaldulensis subsp. refulgens, E. victrix, Melaleuca argentea closed forest over Acacia trachycarpa tall open shrubland over Cyperus vaginatus open sedgeland and Cymbopogon ambiguus scattered tussock grasses. R2: EcEvMgAtrCYPvEUaTHtERItCYa Eucalyptus camaldulensis subsp. refulgens, E. victrix woodland over Melaleuca glomerata, Acacia trachycarpa tall shrubland over Cyperus vaginatus, very open sedgeland and Eulalia aurea, Themeda triandra, Eriachne tenuiculmis, Cymbopogon ambiguus very open tussock grassland. R3: AtrERIt Acacia trachycarpa tall shrubland over Eriachne tenuiculmis scattered tussock grasses. Vegetation of Gorges and Gullies G1: CfPHbTHt Corymbia ferriticola low woodland over Phyllanthus baccatus scattered tall shrubs over Themeda triandra very open tussock grassland. -

Geometric Morphometric Analysis of Cranial Variation in the Egernia Depressa (Reptilia: Squamata: Scincidae) Species Complex Marci G

RECORDS OF THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM 26 138–153 (2011) Geometric morphometric analysis of cranial variation in the Egernia depressa (Reptilia: Squamata: Scincidae) species complex Marci G. Hollenshead Department of Biological Sciences, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, Arizona 86011, U.S.A. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT – Few studies have attempted to simultaneously examine geographic, ontogenetic and sexual variation of lizard crania. This study does so with a focus on the Egernia depressa species complex (Pygmy Spiny-tailed Skinks), which occur throughout much of arid Western Australia and inhabits fallen trees in the southern part of its range and rock crevices in disjunct boulder outcrops in the northern part of its range in the Pilbara. Geometric (i.e. landmark-based) morphometrics were used to examine variation in cranial shape in E. depressa, E. cygnitos and E. epsisolus. Cranial differences were evident among the different species; however, the differences depended on which aspect of the cranium was being analysed. A comparison also was made between E. depressa which inhabits tree hollows v. E. cygnitos and E. epsisolus which use rock crevices. The lateral aspect of the cranium of the rock-inhabiting species differs from the log-inhabiting species in having dorsal-ventral compression of the postorbital region. Egernia cygnitos which lives western portion of the Pilbara differs from other species in having a wider cranium with a correspondingly broader palatal region. Sexual dimorphism was not evident, but ontogenetic changes in cranial form were present. KEYWORDS: Australian skinks, Pygmy Spiny-tailed Skinks, Western Australia, landmark-based methods. INTRODUCTION social groups, several individuals will occupy the same The Australian scincid genus Egernia includes some crevice, bask in close proximity and share the same scat of the continent’s largest and most ubiquitous lizards pile (Duffi eld and Bull 2002). -

GREAT DESERT SKINK TJAKURA Egernia Kintorei

Threatened Species of the Northern Territory GREAT DESERT SKINK TJAKURA Egernia kintorei Conservation status Australia: Vulnerable Northern Territory: Vulnerable Photo: Steve McAlpin Description southern sections of the Great Sandy Desert of Western The great desert skink is a large, smooth bodied lizard with an average snout-vent length of 200 mm (maximum of 440 mm) and a body mass of up to 350 g. Males are heavier and have broader heads than females. The tail is slightly longer than the snout-vent length. The upperbody varies in colour between individuals and can be bright orange- brown or dull brown or light grey. The underbody colour ranges from bright lemon- yellow to cream or grey. Adult males often have blue-grey flanks, whereas those of females and juveniles are either plain brown or vertically barred with orange and cream. Known locations of great desert skink. Distribution The great desert skink is endemic to the Australia. Its former range included the Great Australian arid zone. In the Northern Territory Victoria Desert, as far west as Wiluna, and the (NT), most recent records (post 1980) come Northern Great Sandy Desert. from the western deserts region from Uluru- Conservation reserves where reported: Kata Tjuta National Park north to Rabbit Flat in the Tanami Desert. The Tanami Desert and Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, Watarrka Uluru populations are both global strongholds National Park and Newhaven Reserve for the species. (managed for conservation by the Australian Wildlife Conservancy). Outside the NT it occurs in North West South Australia and in the Gibson Desert and For more information visit www.denr.nt.gov.au Ecology qualifies as Vulnerable (under criteria C2a(i)) due to: The great desert skink occupies a range of • population <10,000 mature individuals; vegetation types with the major habitat being • continuing decline, observed, projected or sandplain and adjacent swales that support inferred, in numbers; and hummock grassland and scattered shrubs. -

The Spectacular Sea Anemone 438 by U

THE AUSTRAL IAN MUSEUM will be 150 years old in March 1977. TAMS has its 5th birthday at the same time. Like all healthy five year olds, TAMS is full of fun, eager to learn about the world and constantly on the go! 1977 is a celebration year. Members enjoy a full and varied programme, are entitled to a discount at the Museum bookshop and have reciprocal rights with many other Societies in Australia and overseas. Join the Society today. THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM SOCIETY 6-8 College Street, Sydney 2000 Telephone: 33-5525 from 1st February, 1977 AUSTRAliAN NATURAl HISTORY DECEMBER 1976 VOLUME 18 NUMBER 12 PUBLISHED QUARTERLY BY THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM, 6-8 COLLEGE STREET, SYDNEY PRESIDENT, MICHAEL PITMAN DIRECTOR, DESMOND GRIFFIN A SATELLITE VIEW OF AUSTRALIA 422 BY J.F . HUNTINGTON A MOST SUCCESSFUL INVASION 428 THE DIVERSITY OF AUSTRALIA'S SKINKS BY ALLEN E. GREER BOTANAVITI 434 TH E ELUSIVE FIJIAN FROGS BY JOHN C. PERNETTA AND BARRY GOLDMAN THE SPECTACULAR SEA ANEMONE 438 BY U. ERICH FRIESE PEOPLE, PIGS AND PUNISHMENT 444 BY O.K . FElL COVER: The sea anemone, Adamsia pal/iata, lives ·com IN REVIEW mensally with the hermit crab, Pagurus prideauxi. (Photo: AUSTRALIAN BIRDS AND OTHER ANIMALS 448 U. E. Friese) A nnual Subscriptio n : $4 .50-Australia; $A5-Papua New Guinea; $A6-other E DITOR/DESIGNE R countr ies. Single copies : $1 ($1.40 posted Australia); $A 1.45-Papua New NANCY SMITH Guinea; $A 1.70-other countries. Cheque or money order p ayable to The ASSISTANT EDITOR Australian Museum should be sent to The Secretary, The Australian Museum, ROBERT STEWART PO Box A285, Sydney South 2000. -

Palatability of Plants to Camels (DBIRD NT)

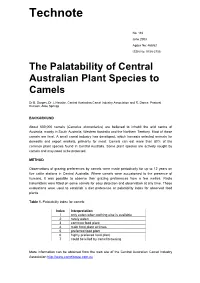

Technote No. 116 June 2003 Agdex No: 468/62 ISSN No: 0158-2755 The Palatability of Central Australian Plant Species to Camels Dr B. Dorges, Dr J. Heucke, Central Australian Camel Industry Association and R. Dance, Pastoral Division, Alice Springs BACKGROUND About 600,000 camels (Camelus dromedarius) are believed to inhabit the arid centre of Australia, mainly in South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory. Most of these camels are feral. A small camel industry has developed, which harvests selected animals for domestic and export markets, primarily for meat. Camels can eat more than 80% of the common plant species found in Central Australia. Some plant species are actively sought by camels and may need to be protected. METHOD Observations of grazing preferences by camels were made periodically for up to 12 years on five cattle stations in Central Australia. Where camels were accustomed to the presence of humans, it was possible to observe their grazing preferences from a few metres. Radio transmitters were fitted on some camels for easy detection and observation at any time. These evaluations were used to establish a diet preference or palatability index for observed food plants. Table 1. Palatability index for camels Index Interpretation 1 only eaten when nothing else is available 2 rarely eaten 3 common food plant 4 main food plant at times 5 preferred food plant 6 highly preferred food plant 7 could be killed by camel browsing More information can be obtained from the web site of the Central Australian Camel Industry Association http://www.camelsaust.com.au 2 RESULTS Table 2. -

Hoser, R. T. 2018. New Australian Lizard Taxa Within the Greater Egernia Gray, 1838 Genus Group Of

Australasian Journal of Herpetology 49 Australasian Journal of Herpetology 36:49-64. ISSN 1836-5698 (Print) Published 30 March 2018. ISSN 1836-5779 (Online) New Australian lizard taxa within the greater Egernia Gray, 1838 genus group of lizards and the division of Egernia sensu lato into 13 separate genera. RAYMOND T. HOSER 488 Park Road, Park Orchards, Victoria, 3134, Australia. Phone: +61 3 9812 3322 Fax: 9812 3355 E-mail: snakeman (at) snakeman.com.au Received 1 Jan 2018, Accepted 13 Jan 2018, Published 30 March 2018. ABSTRACT The Genus Egernia Gray, 1838 has been defined and redefined by many authors since the time of original description. Defined at its most conservative is perhaps that diagnosis in Cogger (1975) and reflected in Cogger et al. (1983), with the reverse (splitters) position being that articulated by Wells and Wellington (1985). They resurrected available genus names and added to the list of available names at both genus and species level. Molecular methods have largely confirmed the taxonomic positions of Wells and Wellington (1985) at all relevant levels and their legally available ICZN nomenclature does as a matter of course follow from this. However petty jealousies and hatred among a group of would-be herpetologists called the Wüster gang (as detailed by Hoser 2015a-f and sources cited therein) have forced most other publishing herpetologists since the 1980’s to not use anything Wells and Wellington. Therefore the most commonly “in use” taxonomy and nomenclature by published authors does not reflect the taxonomic reality. This author will not be unlawfully intimidated by Wolfgang Wüster and his gang of law-breaking thugs using unscientific methods to destabilize zoology as encapsulated in the hate rant of Kaiser et al. -

Sociality in Lizards: Family Structure in Free-Living King's Skinks Egernia

Sociality in lizards: family structure in free-living King’s Skinks Egernia kingii from southwestern Australia C. Masters1 and R. Shine2,3 1PO Box 315, Capel, WA 6271 2School of Biological Sciences A08, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia. 3Corresponding author Prof. Rick Shine ph: 612-9351-3772, fax: 612-9351-5609, email: [email protected] King’s Skinks Egernia kingii are large viviparous scincid lizards from southwestern Australia. Although some other species within the genus Egernia are known to exhibit complex sociality, with long-term associations between adults and their offspring, there are no published records of such behaviour for E. kingii. Ten years’ observations on a single family of lizards (a pair of adults plus six successive litters of their offspring) in a coastal suburban backyard 250 km south of Perth also revealed a very stable adult pair-bond in this species. The female produced litters of 9 to 11 offspring in summer or autumn at intervals of one to three years. In their first year of life, neonates lived with the adult pair and all the lizards basked together; in later years the offspring dispersed but the central shelter-site contained representatives of up to three annual cohorts as well as the parents. Adults tolerated juveniles (especially neonates) and their presence may confer direct parental protection: on one occasion an adult skink attacked and drove away a tigersnake Notechis scutatus that ventured close to the family’s shelter-site. Although our observations are based only on a single pair of lizards and their offspring, they provide the most detailed evidence yet available on the complex family life of these highly social lizards. -

Gidgee Skinks Range from 10.5 to 12 Inches in Length with a Stout Body and Rough Edged Scales, Which Are Used to Help Minimize Water Loss

HHuussbbaannddrryy MMaannuuaall FFoorr GGIIDDGGEEEE SSKKIINNKK EEggeerrnniiaa ssttookkeessiiii Reptilia: Scincidae Compiler: Cindy Jackson Date of Preparation: 14/09/06 Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond Course Name and Number: Certificate III Captive Animal Management Lecturers: Graeme Phipps. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 4 2 TAXONOMY ................................................................................................................................. 5 2.1 NOMENCLATURE .......................................................................................................................... 5 2.2 SUBSPECIES .................................................................................................................................. 5 2.3 RECENT SYNONYMS ..................................................................................................................... 5 2.4 OTHER COMMON NAMES ............................................................................................................. 5 3 NATURAL HISTORY ................................................................................................................... 6 3.1 MORPHOMETRICS ......................................................................................................................... 6 3.1.1 Mass and Basic Body Measurements .........................................................................................