Local Injection Therapy and Neurosurgery for Cervicogenic Effective Date

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peripheral Neurectomies: a Treatment Option for Trigeminal Neuralgia in Rural Practice

Published online: 2019-11-13 Original Article Peripheral neurectomies: A treatment option for trigeminal neuralgia in rural practice Fareedi Mukram Ali, Prasant MC, Deepak Pai1, Vinit A Aher, Sanjay Kar2, Safiya T Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, SMBT Dental College and Hospital, Amrutnagar, Sangamner, 1Consultant Oral & Maxillofacial Surgeon,Sangamner; 2KIMSU, Karad, Maharashtra, India ABSTRACT Background: Trigeminal neuralgia is a commonly diagnosed neurosensory disease of head, neck and face region, involving 5th cranial nerve. Carbamazepine is the first line drug if there is decrease in efficacy or tolerability of medication, surgery needs to be considered. Factors such as pain relief, recurrence rates, morbidity and mortality rates should be taken in to account while considering which technique to use. Peripheral neurectomy is a safe and effective procedure for elderly patients and in rural and remote centers where neurosurgical facilities are not available. It is also effective in those patients who are reluctant for major neurosurgical procedures. Although loss of sensation along the branches of trigeminal nerve and recurrence rate are associated with peripheral neurectomy, we consider it as the safe and effective procedure in rural practice, which can be done under local anesthesia.Aims: The aim of this prospective study is to evaluate the long term efficacy of peripheral neurectomy with and without the placement of stainless steel screws in the foramina and to calculate the mean remission period after peripheral neurectomies for different branches of trigeminal nerve. Setting and Design: The sample was divided into 2 groups by selecting randomly the patients, satisfying inclusion criteria. Both groups were operated under local anesthesia by regional nerve blocks. -

Assessment and Treatment of Dizziness

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;68:129–136 129 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.68.2.129 on 1 February 2000. Downloaded from EDITORIAL Assessment and treatment of dizziness “There can be few physicians so dedicated to their art that they do not experience a slight decline in spirits when they learn that their patient’s complaint is giddiness. This frequently means that after exhaustive enquiry it will still not be entirely clear what it is that the patient feels wrong and even less so why he feels it.” From W B Matthews. Practical Neurology. Oxford, Blackwell, 1963. These words are not quite as true today as when Bryan Convinced? One can be reasonably sure then that the Matthews wrote them nearly 40 years ago. There is now patient who is happy to move around while dizzy does not cause for cautious optimism. Recent clinical and scientific have vertigo, and that the patient who is dizzy all the time developments in the study of the vestibular system have and whose dizziness is not made better by keeping still, made the clinician’s task a little easier. We now know more either hasn’t got vertigo or hasn’t got the story right. Now about the diagnosis and even the treatment of conditions that we are sure that our patient has vertigo the next ques- such as benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo, Menière’s tion to answer is whether the vertigo attacks are spontane- disease, acute vestibular neuritis, migrainous vertigo, and ous or positional. But before we go on to answer that let us bilateral vestibulopathy than we did in 1963 and our consider briefly the diagnosis of other common paroxysmal purpose here is to introduce the clinician to facts worth disorders such as syncope, seizure, hypoglycaemia, and knowing. -

Peripheral Nerve Destruction for Pain Conditions (0525)

Medical Coverage Policy Effective Date ............................................. 3/15/2021 Next Review Date ....................................... 2/15/2022 Coverage Policy Number .................................. 0525 Peripheral Nerve Destruction for Pain Conditions Table of Contents Related Coverage Resources Overview .............................................................. 1 Headache and Occipital Neuralgia Treatment Coverage Policy ................................................... 1 Minimally Invasive Intradiscal/ Annular Procedures General Background ............................................ 2 and Trigger Point Injections Medicare Coverage Determinations .................. 17 Plantar Fasciitis Treatments Coding/Billing Information .................................. 17 Radiofrequency Joint Ablation/Denervation References ........................................................ 29 INSTRUCTIONS FOR USE The following Coverage Policy applies to health benefit plans administered by Cigna Companies. Certain Cigna Companies and/or lines of business only provide utilization review services to clients and do not make coverage determinations. References to standard benefit plan language and coverage determinations do not apply to those clients. Coverage Policies are intended to provide guidance in interpreting certain standard benefit plans administered by Cigna Companies. Please note, the terms of a customer’s particular benefit plan document [Group Service Agreement, Evidence of Coverage, Certificate of Coverage, Summary Plan -

3 Peripheral Nerve Stimulation (PNS) Risk Statement Sheet

Peripheral Nerve Stimulation We have provided the following important information for you to better understand your surgery and to give you the opportunity to ask, and have answered, any questions that may be important to you. Procedure Peripheral Nerve Stimulation (PNS) is a two-step surgical approach to treat chronic pain and headaches. The first stage involves a temporary (3-5 days) trial electrode that is placed according to your distribution of pain. The electrode is connected to an external device that is carried on a belt or in a pocket. At this point the trial electrode will be removed in preparation for stage 2, in which you will have permanent placement of the electrode and implantable pulse generator (IPG). The IPG is implanted under the skin and will be connected to the electrode by a thin extension, also under the skin. I understand that the goal of the procedure is to provide relief of symptoms and improvement of neurologic condition by implanting an electrode that delivers rapid electrical pulses to dampen pain messages send to the brain. However, I am aware and accept that no guarantees about the results of the procedure have been made. I also recognize that unforeseen conditions may require my surgeon and his/her associates and assistants to use different procedures than those indicated above. Alternatives I have considered the alternatives to this procedure, which include: • Observation of the condition without having surgery • Continue medical therapy for relief of pain or muscle spasms • Alternative medical approaches including acupuncture • Alternative surgical approaches including seeking another opinion • Physical therapy that may include deep heat and massage, ultrasound and traction • Injections (i.e. -

Subjective Tests for Vestibular Dysfunction

Global Journal of Otolaryngology ISSN 2474-7556 Powerpoint presentation Glob J Otolaryngol - Special Issue March 2017 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Lalsa Shilpa Perepa DOI: 10.19080/GJO.2017.05.555664 Subjective Tests for Vestibular Dysfunction Basic Advantages a) Well established - criteria for diagnostic testing Indications pontomedullary b) Insights into site of lesion lesions produce ipsiversive tilts (deviation of a) Brandt and Dietrich [2] found that c) Alerts the examiner Pontomesencephalic lesions produce contraversive tilts subjective visual vertical toward the side of the lesion), Basicd) Disadvantages High specificity (away from the lesion). The deviations accompanied by the a) Require New and improvised versions of test ocularb) Disruption tilt reaction. of both the otolithic and vertical b) Not well supported for diagnosing semicircular canal pathways are thought to be involved inc) theThalamic deviations. lesions c) Low sensitivity may produce either ipsiversive or of the parietoinsular vestibular cortex tend to produce Subjectived) Requires Visual objective Vertical tests test to support findings contraversive tilts of subjective visual vertical. Lesions level of the thalamus and above contraversive deviations. Lesions at the Given By-Bohmer A, Rickenmann J [1]. will not produce an accompanying SVV is an estimation technique whereby a subject adjusts a oculard) Lesions tilt reaction. in the inner ear also produce deviation of visible luminescent line, while seated in complete darkness, to subjective visual vertical due to differences in the tonic whatPrinciple they consider to be upright or true vertical. outpute) Abnormal from the inotolithic headache organs in the inner ear [3]. with migraine SVV or SVH a s me a su r ed i n t he upr ig ht posit ion i s i n f luenced sufferers, particularly those byPurpose the utricles, saccules and horizontal semicircular canals. -

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) and Sympathectomy

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) and Sympathectomy H. Hooshmand, M.D. and Eric M. Phillips Neurological Associates Pain Management Center Vero Beach, Florida Abstract. Sympathectomy may provide temporary pain relief, but after a few weeks to months it loses its effect. Sympathectomy and the application of Chemical Sympathectomy (neurolytic agents e.g., phenol, alcohol, etc.) should be limited to patients with life expectancies measured in weeks or months - e.g., cancer patients. Chemical Sympathectomy (e.g., alcohol, phenol or hypertonic saline nerve blocks) aimed at destroying the nerves are apt to fail, to cause serious complications, and aggravation of the pain - by leaving a large scar behind. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) patients should not be exposed to aggravation of pain due to sympathectomy, chemical sympathectomy or radiofrequency sympathectomy. Keywords. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS), Chemical Sympathectomy, Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy (RSD), Sympathectomy, and Radiofrequency Sympathectomy. INTRODUCTION Sympathectomy has been applied for the treatment of causalgia since 1916 (1). The meta analysis of sympathectomy literature for treatment of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) shows high rates of failure. Long term follow-up of 8.4 years showed 13% success (2). Only young teenage soldiers undergoing sympathectomy and followed up to 26-60 days have very good results (3). The rest of the literature has reported a range of 12% up to 97% success rates. The high percentage group has been wartime soldiers which have been diagnosed early, undergone surgery within a few days, and sent home to be lost to follow-up (4-25). Realizing that children and teenagers (such as soldiers), show a strong plasticity and healing power as compared to adults, and realizing that early diagnosis and treatment is more successful, explain the beneficial, albeit temporary, results of wartime sympathectomy (26-29). -

Intraoperative Cranial Nerve Monitoring

CHAPTER 11 Intraoperative Cranial Nerve Monitoring Jack M. Kartush and Alice Lee firmation by an assistant’s hand. As early as 1898, INTRODUCTION Krauze described galvanic stimulation of the facial nerve during an acoustic neurectomy, with visual con- The increasing availability and sophistication of firmation of the response.2 In the 1940s, Olivecrona3 intraoperative cranial nerve monitoring (IOM) made a concerted attempt to routinely preserve the within the last few decades has opened a new era facial nerve during acoustic tumor resections using in the pursuit of functional neural preservation dur- a facial nerve stimulator and a nurse whose respon- ing microsurgery. The use of intraoperative elec- sibility was to observe the patient for facial contrac- tromyographic (EMG) facial nerve monitoring has tions. At times, the surgery was performed under a been a standard of care for the resection of acoustic local anesthetic to allow the patient to move their neuromas and other cerebellopontine angle tumors face upon demand. During the mid-1960s, Parsons, for over a decade.1 Parallel applications are now Jako, and Hilger independently reported on dedi- routinely being used to monitor cranial nerves dur- cated facial nerve monitors that were intended for ing other otolaryngology procedures involving the use during otologic and parotid surgery.4–6 Jako’s parotid gland, thyroid, neck, middle ear, and mas- device was distinguished by a mechanical trans- toid. Although monitoring is becoming more com- ducer placed along the patient’s cheek that detected monly used for these procedures, polls suggest that facial contractions. Delgado et al7 were the first to there is currently no consensus on the role of IOM as report on intraoperative electromyographic (EMG) being a standard of care in these settings. -

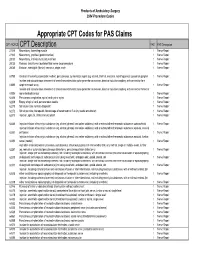

Appropriate CPT Codes for PAS Claims

Products of Ambulatory Surgery 2004 Procedure Codes Appropriate CPT Codes for PAS Claims CPT /HCPCS CPT Description PAS PAS Description 27315 Neurectomy, hamstring muscle 1 Nerve Repair 27320 Neurectomy, popliteal (gastrocnemius) 1 Nerve Repair 28030 Neurectomy, intrinsic musculature of foot 1 Nerve Repair 28035 Release, tarsal tunnel (posterior tibial nerve decompression) 1 Nerve Repair 28080 Excision, interdigital (Morton) neuroma, single, each 1 Nerve Repair 61790 Creation of lesion by stereotactic method, percutaneous, by neurolytic agent (eg, alcohol, thermal, electrical, radiofrequency); gasserian ganglion 1 Nerve Repair Incision and subcutaneous placement of cranial neurostimulator pulse generator or receiver, direct or inductive coupling; with connection to a 61885 single electrode array 1 Nerve Repair Incision and subcutaneous placement of cranial neurostimulator pulse generator or receiver, direct or inductive coupling; with connection to two or 61886 more electrode arrays 1 Nerve Repair 62268 Percutaneous aspiration, spinal cord cyst or syrinx 1 Nerve Repair 62269 Biopsy of spinal cord, percutaneous needle 1 Nerve Repair 62270 Spinal puncture, lumbar, diagnostic 1 Nerve Repair 62272 Spinal puncture, therapeutic, for drainage of cerebrospinal fluid (by needle or catheter) 1 Nerve Repair 62273 Injection, epidural, of blood or clot patch 1 Nerve Repair 62280 Injection/infusion of neurolytic substance (eg, alcohol, phenol, iced saline solutions), with or without other therapeutic substance; subarachnoid 1 Nerve Repair Injection/infusion -

Ganglionectomy of C-2 for the Treatment of Medically Refractory Occipital Neuralgia

Neurosurg Focus 12 (1):Article 14, 2002, Click here to return to Table of Contents Ganglionectomy of C-2 for the treatment of medically refractory occipital neuralgia MICHAEL Y WANG, M.D., AND ALLAN D. O. LEVI, M.D., PH.D. Department of Neurosurgery, University of Miami School of Medicine, Miami, Florida Occipital neuralgia is a result of neuropathic pain transmission in the distribution of the greater occipital nerve. Because it is well anatomically localized, occipital neuralgia has been the focus of various surgical treatments. Ablation, decompression, and modulation of the C-2 nerve have all been described as effective treatments. The C-2 dorsal root ganglionectomy provides effective treatment for this disorder with a low incidence of unpleasant side effects. In this review the authors summarize the current treatment of occipital neuralgia. KEY WORDS • occipital neuralgia • ganglionectomy • headache • rhizotomy Occipital neuralgia is characterized by pain confined to the nerve root gives rise to the dorsal root ganglion, which the distribution of the upper cervical nerve roots. This averages 4.5 mm in width. The obliquus inferior muscle condition most commonly affects the greater occipital overlies the ganglion. nerve and may be related to antecedent trauma. Although The ganglion gives rise to dorsal and ventral rami. The various terms have been used to describe the subjective dorsal ramus contributes several branches, the largest of nature of this discomfort, a lancinating or paroxysmal which is the greater occipital nerve. This nerve passes quality is characteristic. through the semispinalis muscle and then through the Since the initial description of traumatic injury to the attachment of the trapezius muscle to the occipital bone. -

Trigeminal Nerve Block with Alcohol for Medically Intractable Classic Trigeminal Neuralgia: Long-Term Clinical Effectiveness On

Int. J. Med. Sci. 2017, Vol. 14 29 Ivyspring International Publisher International Journal of Medical Sciences 2017; 14(1): 29-36. doi: 10.7150/ijms.16964 Research Paper Trigeminal nerve block with alcohol for medically intractable classic trigeminal neuralgia: long-term clinical effectiveness on pain Kyung Ream Han1, Yun Jeong Chae2, Jung Dong Lee2, Chan Kim3 1. Kichan Pain Clinic, Suwon, Korea; 2. Anesthesiology and Pain medicine, Ajou University Hospital, Suwon Korea; 3. Kimchan Hospital, Suwon, Korea. Corresponding author: [email protected] © Ivyspring International Publisher. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). See http://ivyspring.com/terms for full terms and conditions. Received: 2016.07.24; Accepted: 2016.11.01; Published: 2017.01.01 Abstract Background: Trigeminal nerve block (Tnb) with alcohol for trigeminal neuralgia (TN) may not be used widely as a percutaneous procedure for medically intractable TN in recent clinical work, because it has been considered having a limited duration of pain relief, a decrease in success rate and increase in complications on repeated blocks. Objectives: To evaluate the clinical outcome of the Tnb with alcohol in the treatment of medically intractable TN. Methods: Six hundred thirty-two patients were diagnosed with TN between March 2000 and February 2010. Four hundred sixty-five out of 632 underwent Tnb with alcohol under a fluoroscope. Pain relief duration were analyzed and compared in the individual branch blocks. Outcomes were compared between patients with and without a previous Tnb with alcohol. -

Painful Foot and Ankle

Painful Foot and Ankle American Association of Electrodiagnostic Medicine Tracy A. Park, MD David R. Del Toro, MD Mohammad A. Saeed, MD, MS Atul T. Patel, MD, MHSA Mark E. Easley, MD 2004 AAEM COURSE C AAEM 51st Annual Scientific Meeting Savannah, Georgia Painful Foot and Ankle Tracy A. Park, MD David R. Del Toro, MD Mohammad A. Saeed, MD, MS Atul T. Patel, MD, MHSA Mark E. Easley, MD 2004 COURSE C AAEM 51st Annual Scientific Meeting Savannah, Georgia Copyright © November 2004 American Association of Electrodiagnostic Medicine 421 First Avenue SW, Suite 300 East Rochester, MN 55902 PRINTED BY JOHNSON PRINTING COMPANY, INC. ii Painful Foot and Ankle Faculty Tracy A. Park, MD Mohammad A. Saeed, MD, MS Physiatrist Clinical Associate Professor Medical Rehabilitation Associates Department of Rehabilitation Medicine Milwaukee, Wisconsin University of Washington Dr. Park is currently in private practice at Medical Rehabilitation Seattle, Washington Associates in Milwaukee. In addition, he is an attending physiatrist at both Dr. Saeed received his specialty training in physical medicine and rehabil- St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center and St. Michael’s Hospital in itation at the University of Washington in Seattle, Washington. Following Milwaukee as well as an attending physiatrist at Elmbrook Memorial residency, he served in the United States Army at Madigan Army Medical Hospital in Brookfield, Wisconsin. He performed a physical medicine and Center in Tacoma, Washington, and from 1981-1982 as Chief of the rehabilitation residency at the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago and went Physical Medicine Service. For the past 20 years, he has been in private on to perform a fellowship in electrodiagnostic medicine at the Medical practice, now as senior partner with Electrodiagnosis and Rehabilitation College of Wisconsin. -

Avneesh Chhabra, MBBS, M.D

CURRICULUM VITAE Avneesh Chhabra, MBBS, M.D. PERSONAL INFORMATION Name: Avneesh Chhabra, MBBS, M.D. Office Address: UT Southwestern Medical Center 5323 Harry Hines Blvd., WA1.710 Dallas, TX 75390-9316 Office Phone: 214-645-3465 Fax: Office Email: [email protected] EDUCATION Year Degree Field of Study Institution 1996 MBBS Medicine & Surgery Maulana Azad Medical College, Delhi University, New Delhi, India 1999 MD Radiology Willington Hospital, Delhi University, New Delhi, India POSTDOCTORAL TRAINING Year(s) Titles Specialty/Discipline Institution 1996-1999 Residency Radiology Willington Hospital, Delhi University, New Delhi, India 2002-2003 Internship Internal Medicine Brookdale University Hospital, Brooklyn, NY 2003-2007 Residency Diagnostic Radiology Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA 2007-2008 Fellowship Musculoskeletal Radiology Temple University Hospital, Philadelphia, PA FACULTY ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Year(s) Academic Title Academic Department Academic Institution 2009-2013 Assistant Professor Radiology and Orthopedic Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD Surgery 2013-now Associate Professor Radiology and Orthopedic University of Texas Southwestern Medical School, Dallas, TX Surgery 2013-now Adjunct Faculty Radiology and Orthopedic Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD Surgery 2018-now Adjunct Faculty Radiology Walton Centre of Neurosciences in Manchester, UK CURRENT LICENSURE AND CERTIFICATION License Number M8596/Texas License Expiration 2/28/2020 Primary Spec Diagnostic