Crowsnest!Pass'!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Subdivision Applications and Providing Municipal District of Taber Recommendations

What is ORRSC? MEMBER MUNICIPALITIES Oldman River Regional The Oldman River Regional Services Services Commission Commission (ORRSC) is a cooperative effort of 41 municipalities in southwestern Alberta that provides municipal planning services to Rural: Cardston County Lethbridge County its members. County of Newell Municipal District of Pincher Creek No. 9 ORRSC is responsible for processing Municipal District of Ranchland No. 66 subdivision applications and providing Municipal District of Taber recommendations. The final decision lies Vulcan County with the local municipal Subdivision County of Warner No. 5 BEFORE YOU Authority. Municipal District of Willow Creek No. 26 City: Brooks SUBDIVIDE What is Subdivision? Subdivision is the division of land into 2 or more parcels, each to be given a separate Towns: Municipality of Crowsnest Pass Bassano Milk River title. Cardston Nanton Claresholm Picture Butte Subdivision approval is also required for title Coaldale Pincher Creek separations, property line adjustments, Coalhurst Raymond bareland condominiums and the registration Fort Macleod Stavely of long-term leases. Granum Vauxhall Magrath Vulcan Who Makes the Rules? Villages: Arrowwood Glenwood Barnwell Hill Spring The Province — through the Municipal Barons Lomond Government Act, the Subdivision and Carmangay Milo Development Regulation, and any other Champion Nobleford Government department. Coutts Stirling Cowley Warner The Municipality — through the land use bylaw and adopted statutory plans including Municipal Development Plans, -

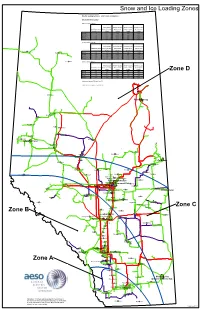

Wet Snow and Wind Loading

Snow and Ice Loading Zones Weather Loading Summary - AESO Tower Development Wet Snow & Wind Loadings 100 Year Return Values Wind Speed Wind Pressure Wind Pressure Wind Pressure Radial Wet Snow (km/hr) at 10m (Pa) at 20 m (Pa) at 30 m (Pa) at 40 m Accretion (mm) Height Height Height Height Zone A 70 77 295 320 340 Zone B 70 71 240 260 280 Zone C 50 67 210 230 245 Zone D 50 64 190 205 220 75 Year Return Values Wind Speed Wind Pressure Wind Pressure Wind Pressure Radial Wet Snow (km/hr) at 10m (Pa) at 20 m (Pa) at 30 m (Pa) at 40 m Accretion (mm) Height Height Height Height Rainbow Lake High Level Zone A 65 75 270 290 310 Zone B 65 70 235 255 270 Zone C 45 65 200 215 230 Zone D 45 62 180 195 210 La Crète 50 Year Return Values Wind Speed Wind Pressure Wind Pressure Wind Pressure Radial Wet Snow (km/hr) at 10m (Pa) at 10 m (Pa) at 20 m (Pa) at 30 m Accretion (mm) Height Height Height Height Zone A 60 74 220 255 280 Zone D Zone B 60 69 190 220 240 Zone C 40 63 160 185 200 Zone D 40 60 145 170 185 Wet snow density 350 kg/m3 at -5C Table Data Last Update: 2010-03-25 Manning Fort McMurray Peace River Grimshaw Fairview Spirit River Falher McLennan High Prairie Sexsmith Beaverlodge Slave Lake Grande Prairie Valleyview Lac la Biche Swan Hills Athabasca Cold Lake Fox Creek Bonnyville Westlock Whitecourt Barrhead Smoky Lake St. -

Magrath Trading Co. Store News

MAGRATH TRADING CO. STORE NEWS PHONES: OFFICE 758-3033 GROCERIES 758-3535 DRY GOODS 758-3252 HARDWARE 758-3065 UPSTAIRS & STORE NEWS 758-6377 STORE HOURS: Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday & Saturday .. 8 a.m. to 6 p.m THURSDAY, MAY 26, 1988......................... ..MAGRATH, ALBERTA ***************************************************************************************** ' UPSTAIRS LADIES WEAR DEPT. ***************************************************************************************** rmilME Blouses Lovely Spring and Summer Blouses in various styles and colors to choose from. Included are sleeveless, short sleeve and long sleeve styles. SKIRTS ‘MINI SKIRTS in Black or Turquoise or White Denim. Zipper front. PRICED FROM Cotton Shorts styled for cool Sumner wearing. Navy or White. SIZES: 8to 14 Runners Hi Top Runners that are so popular now. Tender TgtsiesMM Ltd. Red or Blue Denim with white sole. A new shipment of Tender Totsies has just arrived. , Included are smart dress pumps as well as casuals and flats. CO-ORDINATES PARIS STAR CO-ORDINATES IN A NICE SELECTION OF STYLES, FABRICS AND COLORS. PLAINS AND PRINTS. POLYESTERS DCF & knits........... lUvO Urr SPECIALS SWEATSUITS SEE OUR SALE RACK OF LADIES DRESSES, Terry, Velours, Polyester/Cotton Knits in BLOUSES & COUNTER OF SWEATERS. two piece Jogging Suits. Assorted styles and colors. 1/2 PRICE CLEARING NOW AT 10% OFF Mr. Delay William Loxton of the Alberta Rose Shampoos Lodge and formerly of Magrath, passed away at the Holy Cross Hospital, Calgary, on Wednesday, may Popular Shampoo - 18, 1988 at the age of 67 years. Hillside, Jojoha, Aloe He was bom December 20, 1921 at Coalhurst, & Biotin E. Conditioners 3? and moved to Magrath with his family in 1924. too. He attended school in Magrath. -

Minutes: of the Eleventh Regular Meeting of Council, 2018/2019 Held in Council Chambers on Tuesday, May 7, 2019

MINUTES: OF THE ELEVENTH REGULAR MEETING OF COUNCIL, 2018/2019 HELD IN COUNCIL CHAMBERS ON TUESDAY, MAY 7, 2019 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- COUNCIL: DENNIS CASSIE MAYOR BARBARA EDGECOMBE-GREEN DEPUTY MAYOR HEATHER CALDWELL COUNCILLOR ELIZABETH CHRISTENSEN COUNCILLOR RON LAGEMAAT COUNCILLOR STAFF: KIM HAUTA CHIEF ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICER KYLE BULLOCK DIRECTOR OF CORPORATE SERVICES LESLEY LEBLANC EXECUTIVE ASSISTANT TO THE CAO GALLERY: STAN REYNOLDS RESIDENT Mayor Cassie called the meeting to order at 7:00 p.m. and Councillor Christensen gave the opening prayer. M#5865-19 Mayor Cassie moved the adoption of the Minutes of the Tenth Regular Meeting held April 23, 2019. Carried Unanimously M#5866-19 Mayor Cassie moved the adoption of the Minutes of the Special Meeting held April 30, 2019. Carried Unanimously M#5867-19 Mayor Cassie moved the adoption of the agenda as circulated, with the following amendments: move: 10.g. Meadowlark Estates Residential Subdivision – Coalhurst Site Grading (CLOSED MEETING) to 5.b. Delegations Carried Unanimously DELEGATIONS M#5868-19 Mayor Cassie moved that Council close the meeting to the public for Agenda item 5.a. Director of Corporate Services Kyle Bullock - KPMG 360 Review, as per Section 16 of the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act, at 7:04 p.m. Carried Unanimously Mr. Reynolds left the Council Chambers at 7:04 p.m. M#5869-19 Councillor Lagemaat moved that Council return to open meeting at 7:30 p.m. Carried Unanimously M#5870-19 Deputy Mayor Edgecombe-Green moved that the Council of the Town of Coalhurst hereby authorizes Administration to draft a Financial Management and Fraud Prevention Policy, including a Terms of Reference for a Finance Committee, for future consideration. -

AREA Housing Statistics by Economic Region AREA Housing Statistics by Economic Region

AREA Housing Statistics by Economic Region AREA Housing Statistics by Economic Region AREA Chief Economist https://albertare.configio.com/page/ann-marie-lurie-bioAnn-Marie Lurie analyzes Alberta’s resale housing statistics both provincially and regionally. In order to allow for better analysis of housing sales data, we have aligned our reporting regions to the census divisions used by Statistics Canada. Economic Region AB-NW: Athabasca – Grande Prairie – Peace River 17 16 Economic Region AB-NE: Wood Buffalo – Cold Lake Economic Region AB-W: 19 Banff – Jasper – Rocky Mountain House 18 12 Economic Region AB-Edmonton 13 14 Economic Region AB-Red Deer 11 10 Economic Region AB-E: 9 8 7 Camrose – Drumheller 15 6 4 5 Economic Region AB-Calgary Economic Region AB-S: 2 1 3 Lethbridge – Medicine Hat New reports are released on the sixth of each month, except on weekends or holidays when it is released on the following business day. AREA Housing Statistics by Economic Region 1 Alberta Economic Region North West Grande Prairie – Athabasca – Peace River Division 17 Municipal District Towns Hamlets, villages, Other Big Lakes County - 0506 High Prairie - 0147 Enilda (0694), Faust (0702), Grouard Swan Hills - 0309 (0719), Joussard (0742), Kinuso (0189), Rural Big Lakes County (9506) Clear Hills – 0504 Cleardale (0664), Worsley (0884), Hines Creek (0150), Rural Big Lakes county (9504) Lesser Slave River no 124 - Slave Lake - 0284 Canyon Creek (0898), Chisholm (0661), 0507 Flatbush (0705), Marten Beach (0780), Smith (0839), Wagner (0649), Widewater (0899), Slave Lake (0284), Rural Slave River (9507) Northern Lights County - Manning – 0212 Deadwood (0679), Dixonville (0684), 0511 North Star (0892), Notikewin (0893), Rural Northern Lights County (9511) Northern Sunrise County - Cadotte Lake (0645), Little Buffalo 0496 (0762), Marie Reine (0777), Reno (0814), St. -

Survey Plan and Access Map NOVA Gas Transmission Ltd

NOVA Gas Transmission Ltd. Section 58 Application Monarch Interconnect Facility Modifications Attachment 5 Survey Plan and Access Map NOVA Gas Transmission Ltd. Section 58 Application Attachment 5 Monarch Interconnect Facility Modifications Survey Plan and Access Map February 2015 Page 1 of 3 NOVA Gas Transmission Ltd. Section 58 Application Attachment 5 Monarch Interconnect Facility Modifications Survey Plan and Access Map February 2015 Page 2 of 3 NOVA Gas Transmission Ltd. Section 58 Application Attachment 5 Monarch Interconnect Facility Modifications Survey Plan and Access Map Rge.25 Rge.24 Rge.23 Rge.22 Rge.21 Rge.20 LIC# 02027-065 ATCO GAS AND PIPELINES LTD. (SOUTH) Twp.11 NOBLEFORD PICTURE TS519 BUTTE TS519 -,23 RGE ROAD 23-3 25 Twp.10 COUNTY OF LETHBRIDGE -, +/- 0.12 km LIC# 80270-002 3 -,3A NGTL -, NE-4-10-23-W.4M TS843 COALHURST NW-3-10-23-W.4M Twp.9 MONARCH NORTH 'B' SALES -,3 EXISTING METER STATION COALDALE APPROACH !Ä 3rd BASE LINE TS509 !Ä COMMUNICATION BLOOD LETHBRIDGE CABLE TELUS 148 O/H POWERLINE BLOOD Twp.8 OPERATOR UNKNOWN 10 11 148 4 10-23-4 O/H POWERLINE BLOOD -, 10-23-4 511 148 !Ä 845 ACCESS THROUGH METER STATION FORTIS ALBERTA TS 5 TS -, TS508 PLAN 7610880 Twp.7 NOVA GAS TRANSMISSION LTD. !Ä C OF T: 771 002 734 LIC# 80262-001 NGTL Location Plan OWNER: 1:500,000 NOVA AN ALBERTA CORPORATION. LIC# 80294-001 +/- 0.05 km NGTL Legend LIC# 80270-001 NGTL Primary Highway City / Town C%M Meter Station 1:2,500 Secondary Highway First Nations Minor Roads Metis Settlement I# AGM Temporary Access / Trail Parks / Protected Areas Access Route Railways Telus Trenches (! Access Route Start / End Point ! !Ä Airfields ! Power Transmission Line ^_ Foreign Crossing Location Lake / Water Body / Irrigation Canal Gas Co-Op RGE ROAD 23-3 COUNTY OF LETHBRIDGE River / Creek Licensed Pipeline ^_ Water Crossing +/- 0.12 km Licensed Pipeline (Foreign) TWP ROAD 10-A COUNTY OF LETHBRIDGE +/- 3.48 km MONARCH NORTH 'B' SALES METER STATION 3 2 10-23-4 10-23-4 MONARCH NORTH 'B' SALES METER STATION ACCESS MAP WITHIN Twp. -

Open the Grassland Natural Region Map As

! Natural Regions and Native Prairie ! in Prairie and Parkland Alberta ! ! ! ! Legal ! ! ! Bon Accord ! ! Gibbons ! Bruderheim Morinville ! ! Two Hills Fort Lamont ! St. Albert Saskatchewan Mundare ! TOWN ! ! Edmonton ! CITY Stony Spruce Vegreville Plain Vermilion Grove ! Devon ! ! WATER ! Tofield Lloydminster Beaumont Calmar ! Leduc NATIV!E VEGETATION Viking Millet ! ! NATURAL REGIONS Camrose AND SUBREGIONS ! Wainwright Wetaskiwin Daysland ! PARKLAND NATURAL REGION ! ! Sedgewick Foothills Parkland Killam ! Central Parkland ! Hardisty ! Ponoka GRASSLAND NATURAL REGION Bashaw ! Dry Mixedgrass Lacombe Provost Foothills Fescue ! ! Blackfalds ! ! Stettler Northern Fescue ! ! Mixedgrass Castor ! Red Deer Coronation Penhold ! ! ! Innisfail ! Bowden Trochu ! ! Olds ! Three Hills ! Hanna ! ! Didsbury ! Carstairs ! Drumheller Crossfield ! Oyen ! Airdrie Cochrane ! ! Calgary ! Strathmore ! Chestermere ! Bassano Okotoks ! ! ! Black Diamond Turner Valley ! Brooks High River ! Vulcan ! Nanton Stavely ! Redcliff ! Medicine Vauxhall ! Hat !Claresholm Bow Island ! Picture Butte ! !Granum ! Taber ! Coaldale ! ! Coalhurst Fort Lethbridge Macleod ! ! Pincher ! Raymond Creek Magrath Base Data provided by Spatial Data Warehouse Ltd. Vegetation Data sources: Native Prairie Vegetation Inventory (1991-1993); Central Parkland Native Vegetation v. 1.2 (2002-2004); ! Grassland Vegetation Inventory (2006-2014). Milk River ! Produced by Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development, Cardston South Saskatchewan Region, Regional Informatics Unit, Lethbridge, November 2014. The Minister and the Crown provides this information without warranty or representation as to any matter including but not limited to whether the data / information is correct, accurate or free from error, defect, danger, or hazard and whether it is otherwise useful or suitable for any use the user may make of it. © 2014 Government of Alberta. -

Human-Wildlife Conflict Update Newsletter Bow-Crow Wildlife District

Human-Wildlife Conflict Update Newsletter Bow-Crow Wildlife District This Newsletter will provide updates on Human large urban centres like Calgary, many smaller towns Wildlife Conflict (HWC) trends in the Bow-Crow and hamlets and numerous sparsely populated District including occurrence type, mitigation, agricultural areas. Recreation, industry and predator compensation and mortality numbers. agriculture are also prevalent. This human activity coupled with the presence of large carnivores often results in interactions between the two. This can Background create public safety and property damage concerns The Bow-Crow District extends along the eastern as well as potentially impacting wildlife populations. slopes of the Rocky Mountains, from US border in the southwest, north to the Red Deer River/Hwy 27 boundary, and east to Hwy 2. The District consists Large Carnivore Mitigation of alpine, and montane environments, transitioning A number of proactive mitigation programs exist to the Foothills, before giving way to the agricultural within the District with the aim of reducing negative communities of the prairies. interactions between large carnivores, particularly grizzly bears, and people. These programs are Generally speaking, a wide diversity of wildlife exists r delivered by AEP and various community groups d Dee throughout the District, includinge both black and R RED DEER including the Waterton Biosphere Reserves R iv grizzly bears, cougars and wolves. An abundancee r Innisfail Carnivores and Communities Program, Crowsnest of prey species, including moose, deer0 8.5 and17 25.5 34elk42.5 5are1 59.5 68 Bowden Pass BearSmart, Bow Valley WildSmart and also present. The District is highly populatedTrochu with Sundre Olds Mountainview BearSmart. -

Library Services E-Newsletter Coalhurst

Check it out...from your local library How do I get a library card? What can your library card do for you? Visit your local library to sign up for a library You have free access to over 900 000 items, card (library card fees are determined by each library). 20 000 digital magazines, an e-book and e-audiobook collection as well as a large Residents of Coalhurst can sign up for a card at any Chinook selection of online databases. Arch library. The libraries closest to you are: Picture Butte Municipal Library Borrow books, music and movies Coaldale Public Library Lethbridge Public Library - Main Manage your library materials - renew and place Crossings Branch holds Search online databases for popular magazines, newspapers and journals Where can I use my library card? Download e-books and audiobooks to your Once you have a library card, you can use it at computer or e-reader any Chinook Arch member library. Rate and review books, music and movies Arrrowwood Municipal Library Magrath Public Library Barnwell Public Library Mediatheque Francophone Follow other users with similar tastes to nd your Crowsnest Pass Municipal Library Emma Morier Jim & Mary Kearl Library of Cardston Milk River Municipal Library next great read Carmangay & District Municipal Milo Municipal Library Library Thelma Fanning Memorial Library Champion Public Library Picture Butte Municipal Library Keep a library in your pocket! Chinook Arch Claresholm Municipal Library Pincher Creek & District Mobile makes it easy to nd and discover titles, Coaldale Public Library Municipal Library Coutts Municipal Library Raymond Public Library manage your account, and get the library and Enchant Public Library Stavely Municipal Library availability information you need - anytime and R.C.M.P Centennial Library Theodore Brandley Municipal Glenwood Municipal Library Library anywhere. -

Minutes: of a Special Meeting of Council, 2020/2021 Conducted Through Electronic Means on Tuesday, June 22, 2021

MINUTES: OF A SPECIAL MEETING OF COUNCIL, 2020/2021 CONDUCTED THROUGH ELECTRONIC MEANS ON TUESDAY, JUNE 22, 2021 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- COUNCIL: DENNIS CASSIE MAYOR RON LAGEMAAT DEPUTY MAYOR BARBARA EDGECOMBE-GREEN COUNCILLOR STAFF: KIM HAUTA CHIEF ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICER LESLEY LEBLANC EXECUTIVE ASSISTANT TO THE CAO Mayor Cassie called the meeting to order at 7:00 p.m. Notice of the Special Meeting was provided to Town Council and posted in the Town Office and on the Town’s Social Media sites on June 18, 2021. M#6728-21 Mayor Cassie moved the adoption of the agenda as circulated. Carried Unanimously BUSINESS ARISING 1. Residential Schools: information had been received regarding the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Councillor Heather Caldwell joined the meeting at 7:02 p.m. M#6729-21 Deputy Mayor Lagemaat moved that the Council of the Town of Coalhurst hereby adopts the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as a framework towards reconciliation for the Town of Coalhurst. Carried Unanimously M#6730-21 Deputy Mayor Lagemaat moved that the Council of the Town of Coalhurst hereby recommends that the new Council continue with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action recommendation in terms of providing education for municipal leaders and community and understanding the effects of the Blackfoot people on Coalhurst. Carried Unanimously M#6731-21 Councillor Caldwell moved that the Council of the Town of Coalhurst hereby work together in partnership with Palliser School Division and Barons-Eureka-Warner Family and Community Support Services in regards to the education recommendations in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action within schools, Parent Link Centres and programming. -

Coalhurst Miner Is Killed in Car Crash Nyteimen Attend Gctrden Party Jslls PQT ACTQ Mil Speak Here

IN A L Winnipeg Wheat EDITION Oct. c1o«e • •••)•:•.... 09^ XXt—No.229 LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA. MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 10,1928 12PAGE9 Coalhurst Miner Is Killed In Car Crash NyteiMen Attend Gctrden Party JSllS PQT ACTQ mil Speak Here • • • AOTO SKIDS Thacker Farm At Eutdett Sets Record (From Our Own Correspondent) combine and 3,000 by binder. Betldea hia own holding* Mr. TABER. Sept. 10—Stiff another Thacker haa aharei In a numh«e OFF GRADE. record for threahed wheat bat of the aurroundlng crops. been made for' the 1928 season, The weather In this district it George ThacVer, Burdett farmer, Ideal for harvesting and farmer* aecuring 67 bushels to the acre on are pushing work fast. Combine*, 80 acres Juat cut. This wheat was threshers, binder*, grain truck* •own on summerfallew. Of 1,000 and other harvesting machinery TURNS OVER acre* which Mr. Thacker has In are being puehed to the limit and Canadian Trades and Labor crop, 14,000 bushels of grain have grain Is pouring Into the eleva Congress Votes 10 to I been thireshed, 11,000 cut by the tor*. Accident on Loose Gravel Against Communists Near Traffic Bridge Has FOOTHILLS SCENIC HIGHWAY Fatal Results REFUSE TO SEAT SECRETARY OF PARTY PINCHER CREEK TO WATERTON PARK LIKELY TO BE GRAVELLED THOMAS CONNORS •TORONTO, Sept. Ifl.—Communlgm IS CRASH VICTIM %as rejected by the Trades and Labor DR. Rr C. WALLACE Congress at the opeoing session cf its Pincher Creek Board of Trade Geta Encouraging Letter New President of Alberta University, forty-tourth annual convention here from Public Works Department—Survey to be Made who will pay his first visit to Leth- One man waa killed and two . -

Oldman Watershed Council

Oldman Watershed Council What's Happening at the OWC! Dutch Creek Restoration Event A big thank you to the 50 volunteers who planted willows, gathered leaves, installed signs and built a barricade in Dutch Creek on October 17 and to all the partners and funders for making it possible! Thank you - Volunteers! Our effort to restore a large ford crossing will reduce sediment runoff into the creek which is home to endangered Westslope Cutthroat Trout. Volunteers enjoying a lunch break Read more about the Dutch Creek Restoration Event from one of the volunteers and OWC's Communication Intern Riley Sawyer. Riley Sawyer OWC Lunch and Learn We had our first Lunch and Learn on September 30 to share updates on our Engaging Recreationists and Film Projects and we had many great discussions and networking ice breakers. About 40 people joined us to hear the results from our research over the summer interviewing and surveying off highway vehicle (OHV) recreationists and William Singer III giving update on the backcountry campers, as filming on the Blood Reserve well as reviewing existing information. Our key learning is that there are 2 distinct types of OHV users who are looking for different experiences and therefore have different needs. We now have a much better understanding of Discussion on the the user perspective and will use this research to guide Engaging Recreationists Project the design of our programs for next summer. The film trailer was also shown and we shared how the summer has been very challenging for capturing footage between all the rain, smoke and even ticks.