Angela Carter, A. S. Byatt and Marina Warner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Im Auftrag: Medienagentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 040-5149 1465 [email protected]

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 040-5149 1465 [email protected] The Kinks At The BBC (Box – lim. Import) VÖ: 14. August 2012 CD1 10. I'm A Lover, Not A Fighter - Saturday Club - Piccadilly Studios, 1964 1. Interview: Meet The Kinks ' Saturday Club 11. Interview: Ray Talks About The USA ' -The Playhouse Theatre, 1964 Saturday Club - Piccadilly Studios, 1964 2. Cadillac ' Saturday Club - The Playhouse 12. I've Got That Feeling ' Saturday Club - Theatre, 1964 Piccadilly Studios, 1964 3. Interview: Ray Talks About 'You Really Got 13. All Day And All Of The Night ' Saturday Club Me' ' Saturday Club The Playhouse Theatre, - Piccadilly Studios, 1964 1964 14. You Shouldn't Be Sad ' Saturday Club - 4. You Really Got Me ' Saturday Club - The Maida Vale Studios, 1965 Playhouse Theatre, September 1964 15. Interview: Ray Talks About Records ' 5. Little Queenie ' Saturday Club - The Saturday Club - Maida Vale Studios, 1965 Playhouse Theatre, 1964 16. Tired Of Waiting For You - Saturday Club - 6. I'm A Lover Not A Fighter ' Top Gear - The Maida Vale Studios, 1965 Playhouse Theatre, 1964 17. Everybody's Gonna Be Happy ' Saturday 7. Interview: The Shaggy Set ' Top Gear - The Club -Maida Vale Studios, 1965 Playhouse Theatre, 1964 18. This Strange Effect ' 'You Really Got.' - 8. You Really Got Me ' Top Gear - The Aeolian Hall, 1965 Playhouse Theatre, October 1964 19. Interview: Ray Talks About "See My Friends" 9. All Day And All Of The Night ' Top Gear - The ' 'You Really Got.' Aeolian Hall, 1965 Playhouse Theatre, 1964 20. See My Friends ' 'You Really Got.' Aeolian Hall, 1965 1969 21. -

Andrea-Bianka Znorovszky

10.14754/CEU.2016.06 Doctoral Dissertation Between Mary and Christ: Depicting Cross-Dressed Saints in the Middle Ages (c. 1200-1600) By: Andrea-Bianka Znorovszky Supervisor(s): Gerhard Jaritz Marianne Sághy Submitted to the Medieval Studies Department, and the Doctoral School of History (HUNG doctoral degree) Central European University, Budapest of in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Medieval Studies, and for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History(HUNG doctoral degree) CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2016 10.14754/CEU.2016.06 I, the undersigned, Andrea-Bianka Znorovszky, candidate for the PhD degree in Medieval Studies, declare herewith that the present dissertation is exclusively my own work, based on my research and only such external information as properly credited in notes and bibliography. I declare that no unidentified and illegitimate use was made of the work of others, and no part of the thesis infringes on any person’s or institution’s copyright. I also declare that no part of the thesis has been submitted in this form to any other institution of higher education for an academic degree. Budapest, 07 June 2016. __________________________ Signature CEU eTD Collection i 10.14754/CEU.2016.06 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the dawn, after a long, perilous journey, when, finally, the pilgrim got out from the maze and reached the Holy Land, s(he) is still wondering on the miraculous surviving from beasts, dragons, and other creatures of the desert who tried to stop its travel. Looking back, I realize that during this entire journey I was not alone, but others decided to join me and, thus, their wisdom enriched my foolishness. -

Mewlana Jalaluddin Rumi - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Mewlana Jalaluddin Rumi - poems - Publication Date: 2004 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Mewlana Jalaluddin Rumi(1207 - 1273) Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Balkhi (Persian: ?????????? ???? ?????), also known as Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi (?????????? ???? ????), and more popularly in the English-speaking world simply as Rumi (30 September 1207 – 17 December 1273), was a 13th-century Persian[1][6] poet, jurist, theologian, and Sufi mystic.[7] Iranians, Turks, Afghans, Tajiks, and other Central Asian Muslims as well as the Muslims of South Asia have greatly appreciated his spiritual legacy in the past seven centuries.[8] Rumi's importance is considered to transcend national and ethnic borders. His poems have been widely translated into many of the world's languages and transposed into various formats. In 2007, he was described as the "most popular poet in America."[9] Rumi's works are written in Persian and his Mathnawi remains one of the purest literary glories of Persia,[10] and one of the crowning glories of the Persian language.[11] His original works are widely read today in their original language across the Persian-speaking world (Iran, Tajikistan, Afghanistan and parts of Persian speaking Central Asia).[12] Translations of his works are very popular in other countries. His poetry has influenced Persian literature as well as Urdu, Punjabi, Turkish and some other Iranian, Turkic and Indic languages written in Perso-Arabic script e.g. Pashto, Ottoman Turkish, Chagatai and Sindhi. Name Jalal ad-Din Mu?ammad Balkhi (Persian: ?????????? ???? ????? Persian pronunciation: [d?æl??læddi?n mohæmmæde bælxi?]) is also known as Jalal ad- Din Mu?ammad Rumi (?????????? ???? ???? Persian pronunciation: [d?æl??læddi?n mohæmmæde ?u?mi?]). -

The Register, 1950-05-00

North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University Aggie Digital Collections and Scholarship NCAT Student Newspapers Digital Collections 5-1950 The Register, 1950-05-00 North Carolina Agricutural and Technical State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.library.ncat.edu/atregister Recommended Citation North Carolina Agricutural and Technical State University, "The Register, 1950-05-00" (1950). NCAT Student Newspapers. 108. https://digital.library.ncat.edu/atregister/108 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collections at Aggie Digital Collections and Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in NCAT Student Newspapers by an authorized administrator of Aggie Digital Collections and Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 May 1950 THE REGISTER Page 3 culture. This was quite a gala affair and debating, activities which can aid A Corner In and enhanced the marked increase in him greatly in later life since he wishes Faculty Member of the Year the membership for the Association. to become a lawyer. His most practi We were also fortunate to have mem cal accomplishment is his recent ap The Library bers of the faculty and persons from pointment in the Regular Army as a the city to speak to the association second lieutenant which will become By E. HENRY GIRVEN, '5! on subjects parallel to the members' effective upon the day of his gradua The atmosphere within the main prospective careers. tion and which he earned through reading room is beginning to take on The Association made contributions being designated a distinguished mili that feeling of anxious ominous an lo charity causes and made trips to tary student. -

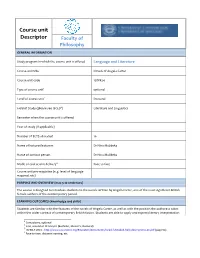

Course Unit Descriptor

Course unit Descriptor Faculty of Philosophy GENERAL INFORMATION Study program in which the course unit is offered Language and Literature Course unit title Novels of Angela Carter Course unit code 15DFk24 Type of course unit1 optional Level of course unit2 Doctoral Field of Study (please see ISCED3) Literature and Linguistics Semester when the course unit is offered Year of study (if applicable) Number of ECTS allocated 10 Name of lecturer/lecturers Dr Nina Muždeka Name of contact person Dr Nina Muždeka Mode of course unit delivery4 Face to face Course unit pre-requisites (e.g. level of language required, etc) PURPOSE AND OVERVIEW (max 5-10 sentences) The course is designed to introduce students to the novels written by Angela Carter, one of the most significant British female authors of the contemporary period. LEARNING OUTCOMES (knowledge and skills) Students are familiar with the features of the novels of Angela Carter, as well as with the position the authoress takes within the wider context of contemporary British fiction. Students are able to apply and express literary interpretation 1 Compulsory, optional 2 First, second or third cycle (Bachelor, Master's, Doctoral) 3 ISCED-F 2013 - http://www.uis.unesco.org/Education/Documents/isced-f-detailed-field-descriptions-en.pdf (page 54) 4 Face-to-face, distance learning, etc. effectively. SYLLABUS (outline and summary of topics) Lectures Angela Carter, contemporary British novel, feminist theory and engaged writing. Shadow Dance as parodic contemporary gothic fiction. Let’s begin countering patriarchal stereotypes: The Magic Toyshop. Several Perceptions: generation gap and the counterculture of the 60s. -

Twist of Fates

PRESENTS TWIST OF FATES COLLECTED POEMS OF AFZAL SHAUQ TRANSLATED BY ALLEY BOLING Twist of Fates Collected poems of Afzal Shauq Translation by Alley Boling Published in Islamabad, Pakistan August 2006 First Edition Contacts Alley Boling, Georgia USA. [email protected] Http://360.yahoo.com/alley_boling2006 Afzal Shauq, Islamabad, Pakistan [email protected] Http://360.yahoo.com/afzalshauq Cover Art by Alley Boling Printed by Faiz ul Islam Printers Pakistan. © All rights reserved to: Alley Boling & Afzal Shauq Half of all proceeds of this book are going to establish the Farishta Foundation to aid the poor and suffering people of this world Retail Price: US$ 19.95 Pak. Rs.300/- Afghani.250/- DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this work to the loved ones in my life .... Who have always had faith in me .... Who supported me in my times of trial .... Who always loved me in spite of my faults. Thank you for always standing by me you special people of my life. Alley Boling ABOUT THE AUTHOR; AFZAL SHAUQ Author M. Afzal Shauq was born in the valleys of the Pashtoon region of North West Pakistan. He attended Balochistan University where he received his masters degree in sociology. In 1998 he received a second masters in Demography from the Cairo Demographic Center in Cairo Egypt. From 1983 - 1986 he being professor lectured on sociology at several Universities. Starting in1986 till the present, he has served as executive officer on Population Welfare. He has work with Radio Pakistan Quetta and different Pakistan Television channels in various positions most notably as a broadcaster, script and lyric writer. -

SF Commentary 106

SF Commentary 106 May 2021 80 pages A Tribute to Yvonne Rousseau (1945–2021) Bruce Gillespie with help from Vida Weiss, Elaine Cochrane, and Dave Langford plus Yvonne’s own bibliography and the story of how she met everybody Perry Middlemiss The Hugo Awards of 1961 Andrew Darlington Early John Brunner Jennifer Bryce’s Ten best novels of 2020 Tony Thomas and Jennifer Bryce The Booker Awards of 2020 Plus letters and comments from 40 friends Elaine Cochrane: ‘Yvonne Rousseau, 1987’. SSFF CCOOMMMMEENNTTAARRYY 110066 May 2021 80 pages SF COMMENTARY No. 106, May 2021, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough, VIC 3088, Australia. Email: [email protected]. Phone: 61-3-9435 7786. .PDF FILE FROM EFANZINES.COM. For both print (portrait) and landscape (widescreen) editions, go to https://efanzines.com/SFC/index.html FRONT COVER: Elaine Cochrane: Photo of Yvonne Rousseau, at one of those picnics that Roger Weddall arranged in the Botanical Gardens, held in 1987 or thereabouts. BACK COVER: Jeanette Gillespie: ‘Back Window Bright Day’. PHOTOGRAPHS: Jenny Blackford (p. 3); Sally Yeoland (p. 4); John Foyster (p. 8); Helena Binns (pp. 8, 10); Jane Tisell (p. 9); Andrew Porter (p. 25); P. Clement via Wikipedia (p. 46); Leck Keller-Krawczyk (p. 51); Joy Window (p. 76); Daniel Farmer, ABC News (p. 79). ILLUSTRATION: Denny Marshall (p. 67). 3 I MUST BE TALKING TO MY FRIENDS, PART 1 34 TONY THOMAS TO MY FRIENDS, PART 1 THE BOOKER PRIZE 2020 READING EXPERIENCE 3, 7 41 JENNIFER BRYCE A TRIBUTE TO YVONNNE THE 2020 BOOKER PRIZE -

The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis

University of Alberta Telling Stories About Storytelling: The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis by Orion Ussner Kidder A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies ©Orion Ussner Kidder Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

Jemf Quarterly

JEMF QUARTERLY JOHN EDWARDS MEMORIAL FOUNDATION VOL. XII SPRING 1976 No. 41 THE JEMF The John Edwards Memorial Foundation is an archive and research center located in the Folklore and Mythology Center of the University of California at Los Angeles. It is chartered as an educational non-profit corporation, supported by gifts and contributions. The purpose of the JEMF is to further the serious study and public recognition of those forms of American folk music disseminated by commercial media such as print, sound recordings, films, radio, and television. These forms include the music referred to as cowboy, western, country & western, old time, hillbilly, bluegrass, mountain, country ,cajun, sacred, gospel, race, blues, rhythm' and blues, soul, and folk rock. The Foundation works toward this goal by: gathering and cataloguing phonograph records, sheet music, song books, photographs, biographical and discographical information, and scholarly works, as well as related artifacts; compiling, publishing, and distributing bibliographical, biographical, discographical, and historical data; reprinting, with permission, pertinent articles originally appearing in books and journals; and reissuing historically significant out-of-print sound recordings. The Friends of the JEMF was organized as a voluntary non-profit association to enable persons to support the Foundation's work. Membership in the Friends is $8.50 (or more) per calendar year; this fee qualifies as a tax deduction. Gifts and contributions to the Foundation qualify as tax deductions. DIRECTORS ADVISORS Eugene W. Earle, President Archie Green, 1st Vice President Ry Cooder Fred Hoeptner, 2nd Vice President David Crisp Ken Griffis, Secretary Harlan Dani'el D. K. Wilgus, Treasurer David Evans John Hammond Wayland D. -

Angela Carter and the Violent Distrust of Metanarratives

Postmodern Openings ISSN: 2068 – 0236 (print), ISSN: 2069 – 9387 (electronic) Coverd in: Index Copernicus, Ideas. RePeC, EconPapers, Socionet, Ulrich Pro Quest, Cabbel, SSRN, Appreciative Inquery Commons, Journalseek, Scipio EBSCO Angela Carter and the Violent Distrust of Metanarratives Ileana BOTESCU – SIRETEANU Postmodern Openings, 2010, Year 1, VOL.3, September, pp: 93-138 The online version of this article can be found at: http://postmodernopenings.com Published by: Lumen Publishing House On behalf of: Lumen Research Center in Social and Humanistic Sciences BOTESCU–SIRETEANU, I.,(2010) Angela Carter and the Violent Distrust of Metanarratives, Postmodern Openings, Year 1, Vol 3, September, 2010, pp: 93-138 Angela Carter and the Violent Distrust of Metanarratives Ileana BOTESCU – SIRETEANU8 Abstract In a world where meaning has been deconstructed and reconstructed, where centers have lost their hegemony and notions such as truth, knowledge or history have been rendered relative by the ongoing ontological enquiry of the postmodern ideology, it is baffling to remark that not only in literature, but also in other fields that make use of discourses, there has been a return to and a reconsideration of the narrative. Nowadays, one can easily observe the narrative drive that enlivens various discourses, from the medical one to the one used in the academe or in official governmental documents. Brian McHale has even referred to the „narrative turn” in literary theory which, according to him, seems to answer to the loss of the metaphysical (McHale 4). Keywords: narrative turn, feminism, narrative dynamics, 8 Ileana BOTESCU – SIRETEANU – “Transilvania” University from Brasov, Romania, Email Address: [email protected]. -

Fairy Tale: a Very Short Introduction by Marina Warner

Volume 37 Number 2 Article 12 Spring 4-17-2019 Fairy Tale: A Very Short Introduction by Marina Warner Barbara L. Prescott Stanford University Alumni Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, and the Folklore Commons Recommended Citation Prescott, Barbara L. (2019) "Fairy Tale: A Very Short Introduction by Marina Warner," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 37 : No. 2 , Article 12. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol37/iss2/12 This Book Reviews is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm This book reviews is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol37/iss2/12 EVIEW ESSAYS NAVIGATING THE C ARTE DU TENDRE IN FA IRY T ALE: A V ERY SH ORT INTRODUCTION BY MAR INA WARNER BARBARA PRESCOTT FAIRY TALE: A VERY SHORT INTRODUCTION. -

Culture and Climate Change: Narratives

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Open Research Online Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Culture and Climate Change: Narratives Edited Book How to cite: Smith, Joe; Tyszczuk, Renata and Butler, Robert eds. (2014). Culture and Climate Change: Narratives. Culture and Climate Change, 2. Cambridge, UK: Shed. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2014 Shed and the individual contributors Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://www.open.ac.uk/researchcentres/osrc/files/osrc/NARRATIVES.pdf Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Culture and Climate Change: Narratives ALICE BELL ROBERT BUTLER TAN COPSEY KRIS DE MEYER NICK DRAKE KATE FLETCHER CASPAR HENDERSON ISABEL HILTON CHRIS HOPE GEORGE MARSHALL RUTH PADEL JAMES PAINTER KELLIE C. PAYNE MIKE SHANAHAN BRADON SMITH JOE SMITH ZOË SVENDSEN RENATA TYSZCZUK MARINA WARNER CHRIS WEST Contributors BARRY WOODS Culture and Climate Change: Narratives Edited by Joe Smith, Renata Tyszczuk and Robert Butler Published by Shed, Cambridge Contents Editors: Joe Smith, Renata Tyszczuk and Robert Butler Design by Hyperkit Acknowledgements 4 © 2014 Shed and the individual contributors Introduction: What sort of story is climate change? 6 No part of this book may be reproduced in any Six essays form, apart from the quotation of brief passages Making a drama out of a crisis Robert Butler 11 for the purpose of review, without the written consent of the publishers.