Gambling Review and Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gambling Commission Submission to the Australian Online Gambling Review

Gambling Commission submission to the Australian online gambling review Inquiry by Joint Select Committee on Gambling Reform into Interactive Gambling – Further Review of Internet Gaming and Wagering June 2011 Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 The Gambling Commission 3 3 The Gambling Act 2005 4 4 Remote gambling 5 5 The Gambling Act 2005: Definition of gambling 5 6 The Gambling Act 2005: Definition of remote gambling 5 7 Licence Conditions and Codes of Practice 5 8 Remote technical standards 6 9 Betting exchanges 7 10 Developments in remote gambling 7 11 Betting Integrity 10 12 Conclusion 14 2 1 Introduction 1.1 This document provides information in response to questions outlined in the 17 May 2011 annoucement by the Joint Select Committee on Gambling Reform on the further review of internet gaming and wagering. 1.2 The responses to the questions in the paper are covered throughout this document and the following highlights the sections in which the answers can be found: (a) the recent growth in interactive sports betting and the changes in online wagering due to new technologies – covered in section 10 (b) the development of new technologies, including mobile phone and interactive television, that increase the risk and incidence of problem gambling – covered in section 10 (c) the relative regulatory frameworks of online and non-online gambling – covered in sections 2 – 8 (d) inducements to bet on sporting events online – covered in section 7.3 (e) The risk of match-fixing in sports as a result of the types of bets available online, and whether -

REGISTER of MEMBERS' INTERESTS As at 26 March 2007

March 2007 Edition REGISTER OF MEMBERS’ INTERESTS as at 26 March 2007 Presented pursuant to the Resolutions of 22nd May 1974, 28th June 1993, 6th November 1995 and 14th May 2002 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 28 March 2007 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS LONDON – THE STATIONERY OFFICE LIMITED 436 REGISTER OF MEMBERS’ INTERESTS INTRODUCTION TO THE MARCH 2007 EDITION This edition of the Register of Members’ Interests is the second to be published for the parliament elected in May 2005, and is up to date as at 26 March 2007. The Register was set up following a Resolution of the House of 22 May 1974. The maintenance of the Register is one of the principal duties laid on the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards by House of Commons Standing Order No. 150. The purpose of the Register is to encourage transparency, and through transparency, accountability. It is “to provide information of any pecuniary interest or other material benefit which a Member receives which might reasonably be thought by others to influence his or her actions, speeches or votes in Parliament, or actions taken in the capacity of a Member of Parliament”1. The Register is not intended to be an indicator of a Member’s personal wealth; nor is registration of an interest in any way an indication that a Member is at fault. Transparency is also promoted by the obligation on Members to declare in debates or proceedings of the House and dealings with other Members, Ministers or Crown servants, all pecuniary interests or benefits of whatever nature, including indirect, past and future interests, which are relevant to the business in hand2. -

The Sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit Era

Island Studies Journal, 15(1), 2020, 151-168 The sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit era Maria Mut Bosque School of Law, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Spain MINECO DER 2017-86138, Ministry of Economic Affairs & Digital Transformation, Spain Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London, UK [email protected] (corresponding author) Abstract: This paper focuses on an analysis of the sovereignty of two territorial entities that have unique relations with the United Kingdom: the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories (BOTs). Each of these entities includes very different territories, with different legal statuses and varying forms of self-administration and constitutional linkages with the UK. However, they also share similarities and challenges that enable an analysis of these territories as a complete set. The incomplete sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and BOTs has entailed that all these territories (except Gibraltar) have not been allowed to participate in the 2016 Brexit referendum or in the withdrawal negotiations with the EU. Moreover, it is reasonable to assume that Brexit is not an exceptional situation. In the future there will be more and more relevant international issues for these territories which will remain outside of their direct control, but will have a direct impact on them. Thus, if no adjustments are made to their statuses, these territories will have to keep trusting that the UK will be able to represent their interests at the same level as its own interests. Keywords: Brexit, British Overseas Territories (BOTs), constitutional status, Crown Dependencies, sovereignty https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.114 • Received June 2019, accepted March 2020 © 2020—Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada. -

Letter to the Gambling Commission

Sarah Gardener Committee of Advertising Practice Executive Director Castle House, 37-45 Paul Street Gambling Commission London EC2A 4LS Telephone 020 7492 2200 Email [email protected] [email protected] www.cap.org.uk 22 October 2020 Dear Sarah Update on CAP and BCAP’s response to the GambleAware research I’m pleased to inform you that CAP and BCAP have today published a consultation proposing significant new restrictions on the creative content of gambling and lotteries advertising. This is an important step in meeting our commitment to respond in full to the emerging findings of the GambleAware research and ensuring that the UK Advertising Codes remain up to date with the evidence base in protecting under-18s and other vulnerable groups. The consultation will run until 22 January and we hope to announce the outcome in the first half of 2021, introducing any changes to the Codes by the end of the year. As well as introducing the consultation, this letter comments on several of the GambleAware recommendations directed at industry or where we have been carrying out policy and enforcement activity separate to the consultation. You’ll be aware that several of the recommendations have been carried over from GambleAware’s Interim Synthesis Report, published in July 2019 Restrictions on adverting volumes We address in the consultation the GambleAware question of whether to strengthen the existing policy (CAP’s ‘25% test’) on where, in non-broadcast media, it is acceptable to place a gambling ad. But, we also note the separate recommendation, directed at industry, to reduce the overall volume of gambling advertising and marketing messages reaching children, young people and vulnerable adults. -

Open PDF 290KB

Public Accounts Committee Oral evidence: Towns Fund, HC 651 Monday 21 September 2020 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 21 September 2020. Watch the meeting Members present: Meg Hillier (Chair); Kemi Badenoch; Olivia Blake; Sir Geoffrey Clifton-Brown; Peter Grant; Mr Richard Holden; Craig Mackinlay; Shabana Mahmood; Mr Gagan Mohindra; James Wild. Gareth Davies, Comptroller and Auditor General, National Audit Office, Lee Summerfield, Director, NAO, and David Fairbrother, Treasury Officer of Accounts, HM Treasury, were in attendance. Questions 1-111 Witnesses I: Jeremy Pocklington, Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, Emran Mian, Director General, MHCLG, and Stephen Jones, Co-Director, Cities and Local Growth Unit, MHCLG. Written evidence from witnesses: Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General Review of the Town Deals selection process (HC 576) Examination of witnesses Witnesses: Jeremy Pocklington, Emran Mian and Stephen Jones. Q1 Chair: Welcome to the Public Accounts Committee on Monday 21 September 2020. We are here today to look at the towns fund. Our thanks go to the National Audit Office, which has done a factual report on money that was allocated to towns, as defined by the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. The money has not been allocated yet, but towns were identified to bid for a pot of funding to improve their area. I will introduce that more formally in a moment. We have a special opportunity today to welcome a member of our Committee who rarely attends because she is the Exchequer Secretary. Kemi Badenoch is a member of the Committee and also a Treasury Minister. -

Uk Government and Special Advisers

UK GOVERNMENT AND SPECIAL ADVISERS April 2019 Housing Special Advisers Parliamentary Under Parliamentary Under Parliamentary Under Parliamentary Under INTERNATIONAL 10 DOWNING Toby Lloyd Samuel Coates Secretary of State Secretary of State Secretary of State Secretary of State Deputy Chief Whip STREET DEVELOPMENT Foreign Affairs/Global Salma Shah Rt Hon Tobias Ellwood MP Kwasi Kwarteng MP Jackie Doyle-Price MP Jake Berry MP Christopher Pincher MP Prime Minister Britain James Hedgeland Parliamentary Under Parliamentary Under Secretary of State Chief Whip (Lords) Rt Hon Theresa May MP Ed de Minckwitz Olivia Robey Secretary of State INTERNATIONAL Parliamentary Under Secretary of State and Minister for Women Stuart Andrew MP TRADE Secretary of State Heather Wheeler MP and Equalities Rt Hon Lord Taylor Chief of Staff Government Relations Minister of State Baroness Blackwood Rt Hon Penny of Holbeach CBE for Immigration Secretary of State and Parliamentary Under Mordaunt MP Gavin Barwell Special Adviser JUSTICE Deputy Chief Whip (Lords) (Attends Cabinet) President of the Board Secretary of State Deputy Chief of Staff Olivia Oates WORK AND Earl of Courtown Rt Hon Caroline Nokes MP of Trade Rishi Sunak MP Special Advisers Legislative Affairs Secretary of State PENSIONS JoJo Penn Rt Hon Dr Liam Fox MP Parliamentary Under Laura Round Joe Moor and Lord Chancellor SCOTLAND OFFICE Communications Special Adviser Rt Hon David Gauke MP Secretary of State Secretary of State Lynn Davidson Business Liason Special Advisers Rt Hon Amber Rudd MP Lord Bourne of -

October Packet -Public.Pdf

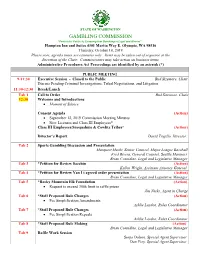

STATE OF WASHINGTON GAMBLING COMMISSION “Protect the Public by Ensuring that Gambling is Legal and Honest” Hampton Inn and Suites 4301 Martin Way E. Olympia, WA 98516 Thursday, October 10, 2019 Please note, agenda times are estimates only. Items may be taken out of sequence at the discretion of the Chair. Commissioners may take action on business items. Administrative Procedures Act Proceedings are identified by an asterisk (*) PUBLIC MEETING 9-11:30 Executive Session - Closed to the Public Bud Sizemore, Chair Discuss Pending Criminal Investigations, Tribal Negotiations, and Litigation 11:30-12:30 Break/Lunch Tab 1 Call to Order Bud Sizemore, Chair 12:30 Welcome and Introductions • Moment of Silence Consent Agenda (Action) • September 12, 2019 Commission Meeting Minutes • New Licenses and Class III Employees* Class III Employees/Snoqualmie & Cowlitz Tribes* (Action) Director’s Report David Trujillo, Director Tab 2 Sports Gambling Discussion and Presentation Marquest Meeks, Senior Counsel, Major League Baseball Fred Rivera, General Counsel, Seattle Mariners Brian Considine, Legal and Legislative Manager Tab 3 *Petition for Review Saechin (Action) Kellen Wright, Assistant Attorney General Tab 4 *Petition for Review Yan Li agreed order presentation (Action) Brian Considine, Legal and Legislative Manager Tab 5 *Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation (Action) • Request to exceed 300k limit in raffle prizes Jim Nicks, Agent in Charge Tab 6 *Staff Proposed Rule Changes (Action) • Fee Simplification Amendments Ashlie Laydon, Rules Coordinator Tab 7 *Staff Proposed Rule Changes (Action) • Fee Simplification Repeals Ashlie Laydon, Rules Coordinator Tab 8 *Staff Proposed Rule Making (Action) Brian Considine, Legal and Legislative Manager Tab 9 Raffle Work Session Sonja Dolson, Special Agent Supervisor Dan Frey, Special Agent Supervisor Public Comment Adjourn Upon advance request, the Commission will pursue reasonable accommodations to enable persons with disabilities to attend Commission meetings. -

Convention on the Manipulation of Sports Competitions Group Of

Birmingham, 24 January 2019 T-MC(2019)3uk Convention on the Manipulation of Sports Competitions Group of Copenhagen – Network of National Platforms National Platform fact sheet UNITED KINGDOM 1. Administrative issues / State of progress State of Progress Operational. Comprises the Sports Betting Intelligence Unit (SBIU) which was formed in 2010 and the Sports betting Integrity Forum (SBIF) which was formed in 2012. Legal Status No basis in law. Actions deliverable through the UK Anti-Corruption Plan1 and Sports and Sport Betting Integrity Plan (The Plan): The Sports Betting Integrity Forum (SBIF) is responsible for delivery of The Plan. Betting Operators are obliged to report suspicious activity to the SBIU, as part of the License Conditions and Codes (condition 15.1) if it relates to or they suspect may relate to the commission of an offence under the Gambling Act (2005), may lead the Commission to take action to void a bet or is a breach of a Sports Governing Bodies betting rules. Responsible Secretariat The SBIU is part of the wider Commission Betting Integrity Programme. The Commission is an independent non-departmental public body (NDPB) sponsored by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). The Commission’s work is funded by fees set by DCMS and paid by the organisations and individuals we license The secretariat of the SBIF is undertaken by the Gambling Commission. Contact persons Lorraine Pearman, [email protected]; + 44 7852 429 168 Organizational form and composition of NP (bodies/entities) The Sports Betting Intelligence Unit (SBIU) is a unit within the Gambling Commission which manages reports of betting-related corruption. -

View Votes and Proceedings PDF File 0.03 MB

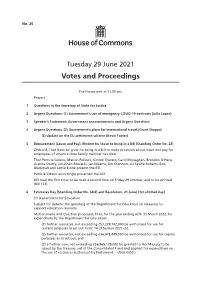

No. 25 Tuesday 29 June 2021 Votes and Proceedings The House met at 11.30 am. Prayers 1 Questions to the Secretary of State for Justice 2 Urgent Questions: (1) Government’s use of emergency COVID-19 contracts (Julia Lopez) 3 Speaker’s Statement: Government announcements and Urgent Questions 4 Urgent Questions: (2) Government’s plans for international travel (Grant Shapps) (3) Update on the EU settlement scheme (Kevin Foster) 5 Bereavement (Leave and Pay): Motion for leave to bring in a Bill (Standing Order No. 23) Ordered, That leave be given to bring in a Bill to make provision about leave and pay for employees of whom a close family member has died; That Patricia Gibson, Marion Fellows, Kirsten Oswald, Carol Monaghan, Brendan O’Hara, Joanna Cherry, Jonathan Edwards, Ian Mearns, Jim Shannon, Liz Saville Roberts, Bob Blackman and Jamie Stone present the Bill. Patricia Gibson accordingly presented the Bill. Bill read the first time; to be read a second time on Friday 29 October, and to be printed (Bill 134). 6 Estimates Day (Standing Order No. 54(2) and Resolution, 21 June) (1st allotted day) (1) Department for Education Subject for debate: the spending of the Department for Education on measures to support education recovery Motion made and Question proposed, That, for the year ending with 31 March 2022, for expenditure by the Department for Education: (1) further resources, not exceeding £53,229,742,000 be authorised for use for current purposes as set out in HC 14 of Session 2021–22, (2) further resources, not exceeding £16,078,449,000 be authorised for use for capital purposes as so set out, and (3) a further sum, not exceeding £56,969,129,000 be granted to Her Majesty to be issued by the Treasury out of the Consolidated Fund and applied for expenditure on the use of resources authorised by Parliament.—(Nick Gibb.) 2 Votes and Proceedings: 29 June 2021 No. -

Gambling Industry Code for Socially Responsible Advertising

Gambling Industry Code for Socially Responsible Advertising 2020 September 6th Edition, GAMBLING INDUSTRY CODE FOR SOCIALLY RESPONSIBLE ADVERTISING 6th Edition October 2020 CONTENTS Introduction paras 1-5 Origins and role of the Industry Code paras 6-11 Legislative, licensing & regulatory context paras 12-18 General principles paras 19-20 Social Responsibility messaging paras 21-25 Inclusion of ‘BeGambleAware’ in advertising paras 26-30 Television advertising – watershed paras 31-40 Television advertising – responsible gambling messaging paras 41-43 Television advertising – text & subtitling para 44 Radio messaging para 45 18+ messaging para 46 Online banner advertising para 47 Sports’ sponsorship para 48 Sponsorship of television programmes paras 49-51 Social media – marketing paras 52-55 Promoting consumer awareness parags 56-57 Search activity paras 58 -60 Affiliate activity paras 61-62 Coverage of the Industry Code paras 63-66 Monitoring and review paras 67-68 Checklist para 69/Annex A and Annex B GAMBLING INDUSTRY CODE FOR SOCIALLY RESPONSIBLE ADVERTISING 6th Edition October 2020 GAMBLING INDUSTRY CODE FOR SOCIALLY ORIGINS AND ROLE OF THE INDUSTRY CODE RESPONSIBLE ADVERTISING 6. The Gambling Act 2005 amended some of 1. The Industry Code for Socially Responsible the longstanding advertising restrictions. Advertising (the ‘Industry Code’) was For example, for the first time it permitted originally introduced on 1 September 2007. television advertising for all forms of gambling. Its aim was to provide gambling operators Before that only very few types of gambling with a range of measures that would enhance such as bingo and the National Lottery the social responsibility of their advertising could be advertised in this way. -

Labour Parties Ideas Transfer and Ideological Positioning: Australia and Britain Compared B.M

Labour parties ideas transfer and ideological positioning: Australia and Britain compared B.M. Edwards & Matt Beech School of Humanities and Social Sciences, The University of New South Wales, Canberra School of Politics, Philosophy and International Studies, University of Hull, UK As part of this special issue examining policy transfer between the Labour Parties in Australia and Britain, this paper seeks to explore the relationship between the two on ideological positioning. In the 1990s there was substantial ideas transfer from the Australian Hawke‐ Keating government to Blair ‘New Labour’ in Britain, as both parties made a lunge towards the economic centre. This paper analyses how the inheritors of that shift, the Rudd/Gillard government in Australia and the Milliband and Corbyn leaderships in Britain, are seeking to define the role and purpose of labour parties in its wake. It examines the extent to which they are learning and borrowing from one another, and finds that a combination of divergent economic and political contexts have led to strikingly limited contemporary policy transfer. Keywords: Australian Labor Party; British Labour Party; Kevin Rudd; Julia Gillard; Ed Miliband; crisis In the 1990s there was substantial policy transfer between the Australian Labor Party and the Labour Party in Britain as they confronted the rise of neoliberalism. The ALP was in power from 1983‐1996 and introduced far reaching market liberalisation reforms complemented by a strengthened safety net. Due to the economic reforms of Thatcherism, Labour in Britain also remade itself to be more pro‐market, drawing considerably on policies of the ALP (Pierson and Castles, 2002). -

Brexit: Gibraltar

HOUSE OF LORDS European Union Committee 13th Report of Session 2016–17 Brexit: Gibraltar Ordered to be printed 21 February 2017 and published 1 March 2017 Published by the Authority of the House of Lords HL Paper 116 The European Union Committee The European Union Committee is appointed each session “to scrutinise documents deposited in the House by a Minister, and other matters relating to the European Union”. In practice this means that the Select Committee, along with its Sub-Committees, scrutinises the UK Government’s policies and actions in respect of the EU; considers and seeks to influence the development of policies and draft laws proposed by the EU institutions; and more generally represents the House of Lords in its dealings with the EU institutions and other Member States. The six Sub-Committees are as follows: Energy and Environment Sub-Committee External Affairs Sub-Committee Financial Affairs Sub-Committee Home Affairs Sub-Committee Internal Market Sub-Committee Justice Sub-Committee Membership The Members of the European Union Select Committee are: Baroness Armstrong of Hill Top Baroness Kennedy of The Shaws Lord Trees Lord Boswell of Aynho (Chairman) Earl of Kinnoull Baroness Verma Baroness Brown of Cambridge Lord Liddle Lord Whitty Baroness Browning Baroness Prashar Baroness Wilcox Baroness Falkner of Margravine Lord Selkirk of Douglas Lord Woolmer of Leeds Lord Green of Hurstpierpoint Baroness Suttie Lord Jay of Ewelme Lord Teverson Further information Publications, press notices, details of membership, forthcoming meetings and other information is available at http://www.parliament.uk/hleu. General information about the House of Lords and its Committees is available at http://www.parliament.uk/business/lords.