Being There Art Assignment 9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Broad Launches Unprecedented Survey of Groundbreaking Artist Shirin Neshat

Media Contacts Tyler Mahowald | [email protected] Justin Conner | [email protected] Alice Chung | [email protected] THE BROAD LAUNCHES UNPRECEDENTED SURVEY OF GROUNDBREAKING ARTIST SHIRIN NESHAT The Artist’s Largest Survey to Date and First Major Exhibition of Her Work in the Western U.S. Will Be on View October 19, 2019–February 16, 2020 in Los Angeles LOS ANGELES—This fall, The Broad will launch a new survey—the largest held to date—of internationally acclaimed artist Shirin Neshat’s work. The exhibition, Shirin Neshat: I Will Greet the Sun Again, will be on view from October 19, 2019, through February 16, 2020, and is the renowned multidisciplinary artist’s first major exhibition to take place in the western United States. The artist has been in the Broad collection for 20 years, beginning with the 1999 acquisition of Rapture (1999)—the first multiscreen video installation to enter the collection. Originated by The Broad, this exhibition surveys approximately 30 years of Neshat’s dynamic video works and photography, investigating the artist’s passionate engagement with ancient and recent Iranian history, the experience of living in exile and the human impact of political revolution. Taking its title from a poem by Iranian poet Forugh Farrokhzad (1934–67), the exhibition begins with her most famous body of work, Women of Allah (1993–97) and features the global debut of Land of Dreams, a new, multi-faceted project that was completed this past summer in New Mexico, and encompasses two videos and a body of photographs. Arranged chronologically, Shirin Neshat: I Will Greet the Sun Again presents over 230 photographs and eight video installations, including iconic video works such as Rapture, Turbulent (1998) and Passage (2001), journeying from works that address specific events in contemporary Iran, both before and after the Islamic Revolution, to work that increasingly uses metaphor and ancient Persian history and literature to reflect on universal concerns of gender, political borders and rootedness. -

Shirin Neshat March 20 - June 1, 2003 BORN in QAZVIN, IRAN, in 1957, Shirin Neshat Came to the United States at Age 17 to Study Art

Shirin Neshat March 20 - June 1, 2003 BORN IN QAZVIN, IRAN, IN 1957, Shirin Neshat came to the United States at age 17 to study art. In 1983 she received a master of fine arts degree from the University of California at Berkeley, where she majored in painting. After graduating she decided not to pursue a career as an artist instead devoting most of her time to co-directing The Storefront for Art and Architecture, an alternative space in New York. It was not until Neshat was in her 30s — after the first of several visits she made in 1990 to her native Iran — that she began making photographs and subsequently videos. She found the country transformed by the dramatic cultural, Made in collaboration with teams of cinematographers, crew, social and political changes of the Islamic Revolution. The sense and casts of hundreds, Neshat’s installations combine powerful of displacement and exile she felt inspired her to devote her cinematic images with mesmerizing soundtracks by such work to an exploration of the profound differences between contemporary composers as Sussan Deyhim and Philip Glass. the Western culture to which she had become assimilated and Her videos do not rely on plots, characters, or dialogue to tell the Eastern culture in which she was raised. In explaining why a story. Instead, the artist’s mysterious narratives unfold she felt compelled to begin making art again she states, “I had through a combination of richly imaginative and carefully reached a sort of intellectual maturity that I didn’t have before. choreographed scenes, dramatic settings, emotive music, and I also finally reached a subject that I felt really connected to. -

Between Two Worlds: an Interview with Shirin Neshat

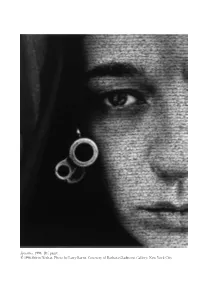

Speechless, 1996. RC print. © 1996 Shirin Neshat. Photo by Larry Barns. Courtesy of Barbara Gladstone Gallery, New York City. Between Two Worlds: An Interview with Shirin Neshat Scott MacDonald A native of Qazvin, Iran, Shirin Neshat finished high school and attended college in the United States and once the Islamic Revolution had transformed Iran, decided to remain in this country. She now lives in New York City, where she is represented by the Barbara Gladstone Gallery. In the mid-1990s, Neshat became known for a series of large photographs, “Women of Allah,” which she designed, directed (not a trained photogra- pher, she hired Larry Barns, Kyong Park, and others to make her images), posed for, and decorated with poetry written in Farsi. The “Women of Allah” photographs provide a sustained rumination on the status and psyche of women in traditional Islamic cultures, using three primary elements: the black veil, modern weapons, and the written texts. In each photograph Neshat appears, dressed in black, sometimes covered completely, facing the camera, holding a weapon, usually a gun. The texts often appear to be part of the photographed imagery. The photographs are both intimate and confrontational. They reflect the repressed status of women in Iran and their power, as women and as Muslims. They depict Neshat herself as a woman caught between the freedom of expression evi- dent in the photographs and the complex demands of her Islamic heritage, in which Iranian women are expected to support and sustain a revolution Feminist Studies 30, no. 3 (Fall 2004). © 2004 by Feminist Studies, Inc. -

Why Video Is the Art Form of the Moment

Jesper JUST Why Video Is the Art Form of the Moment November 2019 1/1 “Why Video Is the Art Form of the Moment” Alina Cohen November 27, 2019 Why Video Is the Art Form of the Moment Alina Cohen Nov 27, 2019 3:37pm Jesper Just, Interpassitivies, at the Royal Danish Theater, 2017. Courtesy of Perrotin. At the 2019 edition of the Venice Biennale, video reigned. Arthur Jafa, who began his career as a cinematographer for commercial directors including Spike Lee and Stanley Kubrick, won the prestigious Golden Lion award for his film The White Album (2018). Meanwhile, one of his frequent collaborators, Kahlil Joseph, who seamlessly crosses between the worlds of music videos and art museums, presented BLKNWS (2019– present), an experimental news media channel aimed at black audiences. Artists including Alex Da Corte, Ian Cheng, Kaari Upson, Ed Atkins, Korakrit Arunanondchai, Stan Douglas , and Hito Steyerl all integrated the medium into dynamic installations. “Video art”—which now encompasses traditional film and digital video as well as a wide range of new media and technology, including virtual reality, video games, and phone apps—represents some of today’s most exciting contemporary work. For further evidence of the medium’s art-world domination, one might examine the artists who were shortlisted for the Turner Prize in 2018 and 2019. All eight—Lawrence Abu “Why Video Is the Art Form of the Moment” Alina Cohen November 27, 2019 Hamdan, Helen Cammock, Oscar Murillo, Tai Shani, Charlotte Prodger, Forensic Architecture, Naeem Mohaiemen, and Luke Willis Thompson—work in video. This video art renaissance derives from an ever-growing range of exhibition methods, improvements in technology, wider institutional acceptance, and artists’ growing ambitions. -

The Mask and the Mirror Curated by Shirin Neshat Leila Heller Gallery November 3 – December 21, 2011

For Immediate Release The Mask and The Mirror curated by Shirin Neshat Leila Heller Gallery November 3 – December 21, 2011 Opening Reception in Chelsea on Thursday, November 3, 6 to 8 p.m. Iké Udé, Sartorial Anarchy: Untitled # 4, 2010. Pigment on satin paper, 40 x 36 in / 101.6 x 91.4 cm Courtesy of the artist New York City – The Mask and The Mirror, an exhibition of self-portraits curated by artist Shirin Neshat, will be on view at Leila Heller Gallery in Chelsea from November 3 through December 21, 2011. The exhibition will take place in the Gallery’s new space at 568 West 25th Street and will present photographs and paintings by 17 artists—some internationally iconic, others emerging and on view for the first time in New York—from the United States, the Middle East, Africa, and Pakistan. An illustrated catalogue will accompany the exhibition. The Mask and The Mirror will include work by Marina Abramović, Matthew Barney, Paolo Canevari, Feridoun Ghaffari, Ramin Haerizadeh, Lyle Ashton Harris, Y.Z. Kami, Shahram Karimi, Robert Mapplethorpe, Youssef Nabil, Nicky Nodjoumi, Bahar Sabzevari, Cindy Sherman, Shahzia Sikander, Iké Udé, Van Leo, and Andy Warhol. Among the highlights of the exhibition are a photograph by Matthew Barney, Drawing Restraint 13: Instrument of Surrender, 2006, with the artist in full military uniform flanked by soldiers, and an untitled color print by Cindy Sherman from 2000 in which she is wearing a yellow wig and outlandish clown makeup. Also included in the exhibition are photographs by Van Leo (1921-2002), whose Hollywood-inspired images of Cairo’s belle époque are considered unrivaled in the Arab world. -

DONALD HAYES RUSSELL 5813 NEVADA AVENUE, NW WASHINGTON, DC 20015 202-213-6272 [email protected] [email protected]

DONALD HAYES RUSSELL 5813 NEVADA AVENUE, NW WASHINGTON, DC 20015 202-213-6272 [email protected] [email protected] EXPERIENCE 2014 - present University Curator, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA ● Directs university fine art collection, exhibitions, public art, artist residencies, donor relations, acquisitions, university partnerships ● Established campus mural program bringing professional artists to work with students 2011- present Research Faculty, College of Visual and Performing Arts, School of Art, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA ● Directs Provisions Research Center for Arts and Social Change in the School of Art, enriching creative research and learning across the University ● Leads Honors Seminar focused on research as art and social practice ● Established research residency program bringing US artists to utilize Washington as a platform for research and project development ● Established and edits Provisional Research Journal ● Serves on the School of Art Advisory Council 2000-present Executive Director, Co-Founder, Provisions Learning Project and Research Center for Art and Social Change, Washington, DC and George Mason University, Fairfax, VA ● Leads research, development and documentation of arts and social change through the library’s collection, online resources, residencies, exhibitions, public art and workshops ● Established collections policy for book, audio/visual and periodical collections covering thirty-three social change topics, called Meridians ● Co-founded, with Edgar Endress, Floating Lab Collective -

The Broad Presents Winter 2017 Season of Diverse Public Programming

For Immediate Release Thursday, Jan. 5, 2017 Media Contact Alex Capriotti | 213-232-6236 | [email protected] THE BROAD PRESENTS WINTER 2017 SEASON OF DIVERSE PUBLIC PROGRAMMING Lineup includes Un-Private Collection conversations featuring Thomas Houseago with Flea, Tony Oursler and Tyler Hubby with Henry Rollins; lecture with artist Ellen Gallagher; performances by Trisha Brown Dance Company and L.A. rap/noise trio clipping.; and film programs to animate the Broad collection of contemporary art Clockwise from top left: Thomas Houseago, photo by Ari Marcopoulos; still from Cooley High, 1975; Ellen Gallagher, photo by © Philippe Vogelenzang / Trunk Archive, courtesy of Gagosian Gallery; Trisha Brown Dance Company, photo by Kat Schleicher; Flea, photo by Clara Balzary; Tony Oursler, photo by Magasin III; clipping., photo by Brian Tamborello; Kim Gordon, photo by David Black. LOS ANGELES—The Broad announced today its winter season of public programming, which will include multiple artist conversations, dance and music performances and film screenings. The winter 2017 public program lineup includes three Un-Private Collection talks, the popular artist conversation series that began in 2013 before The Broad opened. On Jan. 26, Los Angeles artist Thomas Houseago, whose 15-foot tall Giant (Cyclops) sculpture is currently on view in The Broad’s Creature installation, will be in conversation with rock bassist Flea at The Theatre at Ace Hotel. The talk is sponsored by U.S. Trust, Bank of America Private Wealth Management. On March 16 also at The Theatre at Ace Hotel, The Broad will present an evening of film, conversation and music, featuring the West Coast premiere of Tony Conrad: Completely in the Present, followed by a conversation with the documentary’s filmmaker Tyler Hubby and Broad collection artist Tony Oursler, moderated by musician Henry Rollins, about Conrad’s influence on artists including those in the Broad collection. -

Sonido, Cuerpo Y Música: Ubiquitous Listening Y Espacio Autobiográfico En Piezas De Performance Y Video Arte Úrsula San Crist

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi queda condicionat a lʼacceptació de les condicions dʼús establertes per la següent llicència Creative Commons: http://cat.creativecommons.org/?page_id=184 ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis queda condicionado a la aceptación de las condiciones de uso establecidas por la siguiente licencia Creative Commons: http://es.creativecommons.org/blog/licencias/ WARNING. The access to the contents of this doctoral thesis it is limited to the acceptance of the use conditions set by the following Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/?lang=en Facultat de Filosofia i Lletres Departament d’Art i Musicologia Sonido, cuerpo y música: Ubiquitous listening y espacio autobiográfico en piezas de performance y video arte Tesis doctoral de Úrsula San Cristóbal Directora y tutora: Silvia Martínez García Programa en Historia de la Arte y Musicología Bellaterra, Junio de 2020 1 Resumen Esta tesis se ocupa del rol de los elementos sonoros y musicales en piezas que combinan los lenguajes de la performance y del video arte, y que no son consideradas arte sonoro. Propongo las nociones de espacio autobiográfico y ubiquitous listening como instrumentos para analizar obras que abordan aspectos autobiográficos haciendo uso de elementos sonoros y visuales, aportando además una revisión crítica de la bibliografía sobre el sonido y la escucha en el arte contemporáneo. Aplico estas nociones a dos casos de estudio: 1) performances y videos de Marina Abramović realizados entre 1971 y 1997 que permiten comprender el desarrollo de la pieza Balkan Baroque (1997); y 2) las fotografías y video instalaciones de Shirin Neshat realizadas entre 1993 y 1997 que permiten comprender la pieza Turbulent (1998). -

Merve Ertufan Contemporary Art - Course Syllabus

Merve Ertufan Contemporary Art - Course Syllabus Course Description: This course will provide an overview of the origins and the evolution of Contemporary Art. Students will be introduced to predominant trends, concepts and mediums of the 20th and the 21st century through examples and discussions on artworks. We will focus on specific historical, institutional and cultural conditions that make up the backdrop of artistic production, as well as artist’s role and agency in this process. This course aims to equip the students with fundamental knowledge on Contemporary Art, and the necessary intellectual tools for them to be able to critically assess the age that they live in. Course requirements and Grading: %30 Regular attendance, class participation %30 Midterm Exam %40 Final exam Attendance is mandatory and will be monitored. You are expected to arrive on time, having read the weekly assigned readings for that class and prepared to participate in class discussions. Midterm: Midterm exam will be group or individual presentations. You will be expected to hand in your powerpoint in pdf format. Final Exam: For the final exam you will be expected to write a paper on a topic among a set of provided options. Week Title 1 Introduction to the Class; An Overview 2 Modern Movements, Pre-1960s - I 3 Modern Movements, Pre-1960s - II 4 Nouveau réalisme, Arte Povera, Pop Art 5 Minimalism, Conceptual Art 6 Fluxus, Performance Art 7 Midterm Presentations 8 Video Art 9 Body Art, Feminist Art 10 Land Art, Neo-Pop, Neo-Conceptual Art 11 Field Trip 12 Post 1990's: Art Institutions 13 Post 1990's: Predominant Topics 14 New Media Art Week 1: Introduction to the Class, an Overview Week 2: Modern Movements, Pre-1960s - I Overview of the Modern Movements; cultural, historical, and technological context for Contemporary Art. -

ART 4480 Syllabus

ART 4480 SEC. 01 FALL 2006 PROFESSOR SUSAN RYAN!!!! Tues. 3:10 - 6:00 PM Room 213 Design Building VIDEO ART AND THEORY ! ! Tony Oursler, No Skin, 1996, video projected on fiberglass globe As collage technique replaced oil paint, the cathode ray tube will replace the canvas. Nam June Paik 1973 ! ! INTRODUCTION: ! The interest in time-based art has a long history.! In the 19th century gallery goers often viewed paintings at night, by roaring torchlight, in an effort to see images flicker and move.! In the early 20th century, numerous European artists experimented with the new technology of film as a means to expand their work in painting and sculpture.! But film was at first too costly and difficult for artists to produce and distribute.! It was not until 1965 and the availability of the portable camcorder that visual artists on a broad scale (and in the context of conceptual and performance art trends) began to interrelate time, motion, sound, and image and developed a time-based art form distinct from the language of cinema. ! About two thirds of the class focuses on the development of analog video art in the 1960s and 1970s. ! In the last third of the course, the development of digitized video in its various forms (installation, Internet, interactive) will be considered.! The course will be chronological but proceed in terms of major thematic topics, topics that correspond to the principal groupings of “classical” video art but that still provide useful models for approaching new video and its critical literature today. ! Class meets for 3 hours once a week. -

Representations of Rape in Contemporary Women's Art in the US

Anya and Andrew Shiva Gallery John Jay College of Criminal Justice, CUNY 860 11th Avenue, New York, NY 10019 For Immediate Release: THE UN-HEROIC ACT: Representations of Rape in Contemporary Women's Art in the U.S. curated by Monika Fabijanska September 4 – November 2, 2018 Events: Opening reception: Sept. 12, 5:30-8:30 PM First artists talk: Sept. 26, 6-8 PM Symposium: Oct. 3, 5-9 PM Second artists talk: Oct. 24, 6-8 PM Naima Suzanne Lacy, Three Weeks in May, 1977, paper, ink ©1977. Suzanne Lacy. Courtesy of the artist. New York, NY, September 4, 2018 – The Anya and Andrew Shiva Gallery at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, CUNY announces the public programming for the groundbreaking exhibition The Un-Heroic Act: Representations of Rape in Contemporary Women’s Art in the U.S. The exhibition will be on view at 860 Eleventh Avenue (between 58th & 59th Street, ground floor), New York, NY 10019, from September 4 to November 2, 2018, Mon-Fri 10-6. The opening reception will be held on Wednesday, September 12, from 5:30-8:30 PM. The exhibition, curated by Monika Fabijanska, will be accompanied by a catalog and public programming, including a symposium on October 3, 5-9 PM in the Moot Court, John Jay College, as well as exhibition tours and artist talks on September 26 and October 24, 6-8 PM in the gallery. The Un-Heroic Act is a concentrated survey of works by a diverse roster of artists representing three generations – and including Jenny Holzer, Suzanne Lacy, Ana Mendieta, Senga Nengudi, Yoko Ono, and Kara Walker – which aims to fill a gap in the history of art, where the subject of rape has been represented by countless historical depictions by male artists. -

Metropolis TV Lounge 2.Qxd

Gallery 1 Carles Congost (28', 2007) Carles Congost studied fine art, became Events interested in music, and ended up making videos, initially to promote his label The Exhibition Tours Metrópolis TV Lounge Congosound. Music plays an important part in Thu 14 February, 6.00pm & Sun 2 March, his work, yet the videos have become more and 3.00pm more narrative-based and bear a distinctly Join Chris Clarke, Cornerhouse's Visual Arts Fri 1 February - Sun 23 March Education Officer, for an informal biographical undertone. He refers to youth and programme selected by Maria Pallier club culture as well as to the art scene, introductory tour of Metrópolis TV Lounge, Left questioning the distinction between high and but a Trace and Living with Andis. The tour on popular culture, reflecting upon the generational Sun 2 March will be BSL interpreted by Siobhan conflict and investigating relationships of power Rocks. in the Spanish art world. Often incorporating Metrópolis, a weekly television programme about contemporary art and culture, Spanish TV and pop stars as actors, he Free has been airing on the second Channel of TVE (Televisión Española - Spanish parodies television formats and film genres in Public Television) since April 21st, 1985. More than 900 chapters have been order to investigate their role in the construction broadcast nationally, with Metrópolis still following the original format - a 25 of identity. One Hour Intro: Metrópolis TV Lounge minute thematic programme that has achieved cult status as a showcase for (Programme 5: (Projection) Wed 5 March, 6.00pm emerging and acclaimed artists. Metrópolis has become a preeminent forum for Maria Pallier, the curator of Metrópolis TV video art, experimental film, short fiction, creative documentaries, dance films, Cities: Manchester 1 + Cities: Manchester 2 Lounge, will speak about her role as editor of music videos and creative, innovative commercials, all of which constitute the ( 32' + 34', 1990) the weekly arts and culture programme, and programme's main content.