Sebuah Kajian Pustaka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with Financial Assistance from the World Bank

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT (KSWMP) INTRODUCTION AND STRATEGIC ENVIROMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE Public Disclosure Authorized MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA VOLUME I JUNE 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by SUCHITWA MISSION Public Disclosure Authorized GOVERNMENT OF KERALA Contents 1 This is the STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA AND ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK for the KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with financial assistance from the World Bank. This is hereby disclosed for comments/suggestions of the public/stakeholders. Send your comments/suggestions to SUCHITWA MISSION, Swaraj Bhavan, Base Floor (-1), Nanthancodu, Kowdiar, Thiruvananthapuram-695003, Kerala, India or email: [email protected] Contents 2 Table of Contents CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE PROJECT .................................................. 1 1.1 Program Description ................................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Proposed Project Components ..................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Environmental Characteristics of the Project Location............................... 2 1.2 Need for an Environmental Management Framework ........................... 3 1.3 Overview of the Environmental Assessment and Framework ............. 3 1.3.1 Purpose of the SEA and ESMF ...................................................................... 3 1.3.2 The ESMF process ........................................................................................ -

Accused Persons Arrested in Idukki District from 12.07.2015 to 18.07.2015

Accused Persons arrested in Idukki district from 12.07.2015 to 18.07.2015 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, Rank which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Door No.9/39, 315/15, JFMC 49, Cumbum Street, 12/07/15, K A Shaji SI 1 Selvaraj Chinnaswamy Sankurundan u/s.17 of KML Vandanmedu Nedumkanda Male Mettu Bhagom, 1.10 pm Vandanmedu Act m Cumbum. Kunnathu Illam, Cr.313/15, JFMC 19, 12/07/15, K A Shaji SI 2 Ajmal Asharaf Mattancherry, Vandanmedu u/s.20(b) (ii) Vandanmedu Nedumkanda Male 8.45 am Vandanmedu Ernakulam of NDPS Act m I K Vilasam, Cr.313/15, JFMC 19, 12/07/15, K A Shaji SI 3 Nimshad Nazeer Mattancherry, Fort Vandanmedu u/s.20(b) (ii) Vandanmedu Nedumkanda Male 8.45 am Vandanmedu Kochi, Ernakulam of NDPS Act m Mullasseril House, 240/09, CPO 2801, JFMC 35, 13/07/15, Nedumkanda 4 Sajeer Muhammad Kalkoonthal, Peermade u/s.324 IPC CPO 3172, Nedumkanda Male 7 PM m Nedumkandam (LP 28/11) CPO 3572 m Cr.274/15, u/s.17 of KML Act sec. 3 Cheenickal House, r/w. 9 of 34, Udumbannoor, Chakkappan 14/07/15, M A Sabu, CJMC,THODUP 5 Saju Ibrahim Kerala Karimannoor Male Edamaruk, kavala 5.20 pm Addl. SI UZHA Prohibition of Mankuzhy charging Exorbitant Interest Act Kadankulam House, Cr.132/15, 33, Mailappuzha, 14/07/15, C V Abraham, 6 Sijo George George Eettikkavala u/s.55(a) (1) Kanjikuzhy JFMC Idukki Male Pazhayarikkandam, 12 am SI Kanjikuzhy of Abkari Act Kanjikuzhy. -

Payment Locations - Muthoot

Payment Locations - Muthoot District Region Br.Code Branch Name Branch Address Branch Town Name Postel Code Branch Contact Number Royale Arcade Building, Kochalummoodu, ALLEPPEY KOZHENCHERY 4365 Kochalummoodu Mavelikkara 690570 +91-479-2358277 Kallimel P.O, Mavelikkara, Alappuzha District S. Devi building, kizhakkenada, puliyoor p.o, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 4180 PULIYOOR chenganur, alappuzha dist, pin – 689510, CHENGANUR 689510 0479-2464433 kerala Kizhakkethalekal Building, Opp.Malankkara CHENGANNUR - ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 3777 Catholic Church, Mc Road,Chengannur, CHENGANNUR - HOSPITAL ROAD 689121 0479-2457077 HOSPITAL ROAD Alleppey Dist, Pin Code - 689121 Muthoot Finance Ltd, Akeril Puthenparambil ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2672 MELPADAM MELPADAM 689627 479-2318545 Building ;Melpadam;Pincode- 689627 Kochumadam Building,Near Ksrtc Bus Stand, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2219 MAVELIKARA KSRTC MAVELIKARA KSRTC 689101 0469-2342656 Mavelikara-6890101 Thattarethu Buldg,Karakkad P.O,Chengannur, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1837 KARAKKAD KARAKKAD 689504 0479-2422687 Pin-689504 Kalluvilayil Bulg, Ennakkad P.O Alleppy,Pin- ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1481 ENNAKKAD ENNAKKAD 689624 0479-2466886 689624 Himagiri Complex,Kallumala,Thekke Junction, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1228 KALLUMALA KALLUMALA 690101 0479-2344449 Mavelikkara-690101 CHERUKOLE Anugraha Complex, Near Subhananda ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 846 CHERUKOLE MAVELIKARA 690104 04793295897 MAVELIKARA Ashramam, Cherukole,Mavelikara, 690104 Oondamparampil O V Chacko Memorial ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 668 THIRUVANVANDOOR THIRUVANVANDOOR 689109 0479-2429349 -

The Continuing Decline of Hindus in Kerala

The continuing decline of Hindus in Kerala Kerala—like Assam, West Bengal, Purnia and Santhal Pargana region of Bihar and Jharkhand, parts of Western Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand, Mewat of Haryana and Rajasthan, and many of the States in the northeast—has seen a drastic change in its religious demography in the Census period, beginning from 1901. The share of Indian Religionists in Kerala, who are almost all Hindus, has declined from nearly 69 percent in 1901 to 55 percent in 2011, marking a loss of 14 percentage points in 11 decades. Unlike in the other regions mentioned above, in Kerala, both Christians and Muslims have considerable presence and both have gained in their share in this period. Of the loss of 14 percentage points suffered by the Indian Religionists, 9.6 percentage points have accrued to the Muslims and 4.3 to the Christians. Christians had in fact gained 7 percentage points between 1901 and 1961; after that they have lost about 3 percentage points, with the rapid rise in the share of Muslims in the recent decades. This large rise in share of Muslims has taken place even though they are not behind others in literacy, urbanisation or even prosperity. Notwithstanding the fact that they equal others in these parameters, and their absolute rate of growth is fairly low, the gap between their growth and that of others remains very wide. It is wider than, say, in Haryana, where growth rates are high and literacy levels are low. Kerala, thus, proves that imbalance in growth of different communities does not disappear with rising literacy and lowering growth rates, as is fondly believed by many. -

Idukki Travel Guide - Page 1

Idukki Travel Guide - http://www.ixigo.com/travel-guide/idukki page 1 Famous For : City Jul Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, When To umbrella. Idukki Thodupuzha, the entry point, is 65 km east Max: Min: Rain: of Kochi. District capital Painavu, 40 km Visit the 40-km stretch of Idukki, 29.29999923 23.70000076 516.099975585937 away, is the access point for the dams on 7060547°C 2939453°C 5mm watered by the Periyar River, which VISIT the Periyar River that are the highlights of Aug offers many sights in central Idukki this region. The Malankara Reservoir, spread http://www.ixigo.com/weather-in-idukki-lp-1185719 Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, District. You’ll find gentle green hills over 11 km, is a popular picnic spot. A steep umbrella. Max: 29.5°C Min: Rain: 330.5mm and no organised tourism. climb up the 2,685-foot-high Kurusha Para Jan 24.10000038 hill offers a breathtaking view of the 1469727°C Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen. reservoir and the plantations around. Max: 31.5°C Min: Rain: Sep Thomankuttu is a series of cascading 23.10000038 32.2999992370605 Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, 1469727°C 5mm waterfalls. Rainbow Waterfalls, surrounded umbrella. Feb Max: 30.0°C Min: Rain: by lush forests, gush down from 4,921 ft, 25 24.20000076 283.799987792968 km from Thodupuzha. Said to be among the Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen. 2939453°C 75mm Max: Min: Rain: highest peaks in Kerala, the Kudayathoor 31.79999923 24.10000038 24.2999992370605 Oct Mala rises 3,680 ft. -

JETIR Research Journal

© 2018 JETIR December 2018, Volume 5, Issue 12 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Learning from the Past: Study on Sustainable Features from Vernacular Architecture in Coastal Karnataka. 1Vikas.S.P, 2Sagar.V.G, 3Manoj Kumar.G, 4Neeraja Jayan 1Student, 6th sem, School of Architecture, REVA UNIVERSITY, 2Student, 6th sem, School of Architecture, REVA UNIVERSITY, 3Student, 6th sem, School of Architecture, REVA UNIVERSITY, 4Associate Professor, School of Architecture, REVA UNIVERSITY. Abstract: Vernacular architecture can be defined as that architecture characterized based on the function, construction materials and traditional knowledge specific and unique to its location. It is indigenous to a specific time and place and also incorporates the skills and expertise of local builders. The paper is elaborated on the basis of case studies of settlements in the Coastal region of Karnataka with special reference to Barkur and Brahmavar of Udupi regions. It has evolved over generations with the available building materials, climatic conditions and local craftsmanship. However, some examples of vernacular architecture are still found in Barkur and Brahmavar. These vernacular residential dwellings provided with various passive solar techniques including natural cooling systems and are more comfortable compared to the contemporary buildings in today's context. This research paper into various parameters which defines the vernacular architecture of coastal Karnataka and how these parameters can be interpreted in today’s context so that it can be used effectively in the future residential designs. keywords - sustainable, vernacular architecture, modern building, sustainability. I. INTRODUCTION Udupi is a city in the southwest Indian state of Karnataka and is known for its Hindu temples, including the 13th century Krishna temple which houses the statue of lord Krishna. -

Trusting E-Voting Amidst Experiences of Electoral Malpractice: the Case Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loughborough University Institutional Repository Trusting e-voting amidst experiences of electoral malpractice: the case of Indian elections Chrisanthi Avgerou, Silvia Masiero, Angeliki Poulymenakou Journal of Information Technology, accepted 14.09.2018 Abstract This paper constructs explanatory theory on trust in e-voting, a term that refers to the use of stand-alone IT artefacts in voting stations. We study e-voting as a techno-organisational arrangement embedded in the process of elections and the broader socio-economic context of a country. Following a critical realist approach, we apply retroduction and retrodiction principles to build theory by complementing existing studies of e-voting with insights from an in-depth case study of elections in India. First, we seek evidence of trust in e-voting in the responses of the public to the announcement of election results. Then we derive the following four mechanisms of trust creation or loss: the association of e-voting with the production of positive democratic effects; the making of e-voting part of the mission and identity of electoral authorities; the cultivation of a positive public attitude to IT with policies for IT-driven socio-economic development; and, in countries with turbulent political cultures, a clear distinction between the experience of voting as orderly and experiences of malpractice in other election tasks. We suggest that these mechanisms explain the different experience with e-voting of different countries. Attention to them helps in assessing the potential of electoral technologies in countries that are currently adopting them, especially fragile democracies embarking upon e-voting. -

Paddy Cultivation in Kerala: a Trend Analysis of Area, Production and Productivity at District Level M. P. Abraham

Paddy Cultivation in Kerala: A Trend Analysis of Area, Production and Productivity at District Level (1980-81 to 2012-13) M. P. Abraham Assistant Professor Department of Economics Government College, Attingal July, 2019 1 Abstract The agriculture in Kerala has undergone significant structural changes in the form of decline in the share of Gross State Domestic Product and commercialization of agriculture. The gross cropped area and the net sown area in the state have declined over a period of time. The changes in land utilization pattern in the form of massive conversion of paddy lands for the cultivation of cash crops and for non-agricultural purposes have landed Kerala in a state of food insecurity. They have also created many social, environmental and ecological problems in the state. Coconut and rubber, the principal rival crops of paddy, have occupied the lion share of paddy area over a period of time. The area and production of paddy have been continuously declining in Kerala and their growth rate has become the highest negative during 1990s. The decline in the production of paddy would have been much higher, had there been no positive change in the yield. The highest negative growth rate in area under paddy is found in Kollam district and lowest in Palakkad district during the period 1980-81 to 2011-12. The highest negative growth rate in paddy production is found in Kollam district and lowest in Alappuzha district. However, the overall growth rate of productivity of paddy is positive in all districts. In all districts, the area effect and interaction effect on paddy production is negative and yield effect is positive. -

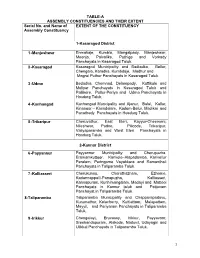

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

Ernakulam District, Kerala State

TECHNICAL REPORTS: SERIES ‘D’ CONSERVE WATER – SAVE LIFE भारत सरकार GOVERNMENT OF INDIA जल संसाधन मंत्रालय MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES कᴂ द्रीय भूजल बो셍 ड CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD केरल क्षेत्र KERALA REGION भूजल सूचना पुस्तिका, एर्ााकु लम स्ज쥍ला, केरल रा煍य GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF ERNAKULAM DISTRICT, KERALA STATE तत셁वनंतपुरम Thiruvananthapuram December 2013 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF ERNAKULAM DISTRICT, KERALA 饍वारा By टी. एस अनीता �याम वैज्ञातनक ग T.S.Anitha Shyam Scientist C KERALA REGION BHUJAL BHAVAN KEDARAM, KESAVADASPURAM NH-IV, FARIDABAD THIRUVANANTHAPURAM – 695 004 HARYANA- 121 001 TEL: 0471-2442175 TEL: 0129-12419075 FAX: 0471-2442191 FAX: 0129-2142524 GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF ERNAKULAM DISTRICT, KERALA STATE TABLE OF CONTENTS DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 1 2.0 RAINFALL AND CLIMATE ................................................................................... 4 3.0 GEOMORPHOLOGY AND SOIL ............................................................................ 5 4.0 GROUND WATER SCENARIO .............................................................................. 6 5.0 GROUND WATER DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGEMENT .......................... 13 6.0 GROUND WATER RELATED ISSUES AND PROBLEMS ................................ 13 7.0 AWARENESS AND TRAINING ACTIVITY ...................................................... -

KERALA STATE CONGRESS SEVA DAL OB LIST.Pdf

State Office Bearers of Kerala Pradesh Chief Organiser 1 Shri M.A. Salam Shri M.A.Salam Chief Organiser Chief Organiser Kerala Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Kerala Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Indira Bhawan Kottavila Veedu, Vellayambalam Pathirickal-PO-689695 Pathanapuram Thiruvananthapuram –10 Kollam(Kerala) Kerala Tel-09446796565,9074758062 Tel-0471-2311500,2721401,2720629 email- [email protected] Additional Chief Organiser 1 Shri A.P. Ravindran Additional Chief Organiser Kerala Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Adipparampil House West Nadakkavu Calicut-11 Kerala Tel-09847377086 Mahila Organiser 1 Smt. Krishna Kumari Ravi Mahila Organiser Kerala Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Chakamadathil House Nhangattiri Post- 679311 Pattambi Palaghat ( Kerala) Tel: 09895783462 Chief Instructor 1 Shri N.J. Prabhulla Chandran Chief Instructor Kerala Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Nalini Nilayam Kaliyoor Trivandrum, Kerala Tel: 09645061314, 0471-2162649 State Organisers 1 Shri P.K. Peter 2 Shri Joseph Inchiparamban Organiser Organiser Kerala Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Kerala Pradesh Congress Seva dal 815/36, Pazhannan House Inchiparambil House Desabhimani Road Vazhappalli P.O. Kaloor, Cochin Changanassery Kerala Kottayam, Kerala Tel: 0484- 2537545 Tel-0481-2423047,09447455741 3 Shri P.P.Babu 4 Smt.P.C. Karthiyayani Organiser Organiser Kerala Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Kerala Pradesh Congress Seva Dal "Sindu", Sathram Road Puthenpurayil House Thilannure, Kapad-PO-670006 Tandarapara-PO Kannur, Kerala Cayonna, Tel: 04972-821522, 09447394711 Calicut(Kerala) 5 Shri Jose Mathew 6 Shri C.H. Vijayan Organiser Organiser Kerala Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Kerala Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Neeranal House Punndur House Koompanpara –PO Nakraji- 671544 Adimali,Idukki Kasargode, Kerala Kerala Tel: 04994-290055,285510 7 Shri P. -

Kerala – CPI-M – BJP – Communal Violence – Internal Relocation

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: IND34462 Country: India Date: 25 March 2009 Keywords: India – Kerala – CPI-M – BJP – Communal violence – Internal relocation This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide brief information on the nature of the CPI-M and the BJP as political parties and the relationship between the two in Kerala state. 2. Are there any reports of Muslim communities attacking Hindu communities in Kerala in the months which followed the 1992 demolition of Babri Masjid in Ayodhya? If so, do the reports mention whether the CPI-M supported or failed to prevent these Muslim attacks? Do any such reports specifically mention incidents in Kannur, Kerala? 3. With a view to addressing relocation issues: are there areas of India where the BJP hold power and where the CPI-M is relatively marginal? 4. Please provide any sources that substantiate the claim that fraudulent medical documents are readily available in India. RESPONSE 1. Please provide brief information on the nature of the CPI-M and the BJP as political parties and the relationship between the two in Kerala state.