That Terrible Hour’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GP Text Paste Up.3

FACING ASIA A History of the Colombo Plan FACING ASIA A History of the Colombo Plan Daniel Oakman Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/facing_asia _citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry Author: Oakman, Daniel. Title: Facing Asia : a history of the Colombo Plan / Daniel Oakman. ISBN: 9781921666926 (pbk.) 9781921666933 (eBook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Economic assistance--Southeast Asia--History. Economic assistance--Political aspects--Southeast Asia. Economic assistance--Social aspects--Southeast Asia. Dewey Number: 338.910959 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Emily Brissenden Cover: Lionel Lindsay (1874–1961) was commissioned to produce this bookplate for pasting in the front of books donated under the Colombo Plan. Sir Lionel Lindsay, Bookplate from the Australian people under the Colombo Plan, nla.pic-an11035313, National Library of Australia Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press First edition © 2004 Pandanus Books For Robyn and Colin Acknowledgements Thank you: family, friends and colleagues. I undertook much of the work towards this book as a Visiting Fellow with the Division of Pacific and Asian History in the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University. There I benefited from the support of the Division and, in particular, Hank Nelson and Donald Denoon. -

Legislative Assembly

11282 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Wednesday 22 September 2004 ______ Mr Speaker (The Hon. John Joseph Aquilina) took the chair at 11.00 a.m. Mr Speaker offered the Prayer. MINISTRY Mr BOB CARR: In the absence of the Minister for Tourism and Sport and Recreation, and Minister for Women, who is undergoing an operation, the Deputy Premier, Minister for Education and Training, and Minister for Aboriginal Affairs will answer questions on her behalf. In the absence of the Minister for Mineral Resources, the Minister for Fair Trading, and Minister Assisting the Minister for Commerce will answer questions on his behalf. In the absence of the Minister for Infrastructure and Planning, and Minister for Natural Resources, the Attorney General, and Minister for the Environment will answer questions on his behalf. DISTINGUISHED VISITORS Mr SPEAKER: I welcome to the Public Gallery Mrs Sumitra Singh, the Speaker of the Legislative Assembly of the State of Rajasthan in India, who is accompanied by her son, and Mrs Harsukh Ram Poonia, Secretary of the Rajasthan Legislative Assembly. PETITIONS Milton-Ulladulla Public School Infrastructure Petition requesting community consultation in the planning, funding and building of appropriate public school infrastructure in the Milton-Ulladulla area and surrounding districts, received from Mrs Shelley Hancock. Gaming Machine Tax Petitions opposing the increase in poker machine tax, received from Mrs Shelley Hancock, Mrs Judy Hopwood and Mr Andrew Tink. Crime Sentencing Petition requesting changes in legislation to allow for tougher sentences for crime, received from Mrs Shelley Hancock. Lake Woollumboola Recreational Use Petition opposing any restriction of the recreational use of Lake Woollumboola, received from Mrs Shelley Hancock. -

04 Chapters 8-Bibliography Burns

159 CHAPTER 8 THE BRISBANE LINE CONTROVERSY Near the end of March 1943 nineteen members of the UAP demanded Billy Hughes call a party meeting. Hughes had maintained his hold over the party membership by the expedient of refusing to call members 1a together. For months he had then been able to avoid any leadership challenge. Hughes at last conceded to party pressure, and on 25 March, faced a leadership spill, which he believed was inspired by Menzies. 16 He retained the leadership by twenty-four votes to fifteen. The failure to elect a younger and more aggressive leader - Menzies - resulted in early April in the formation by the dissenters of the National Service Group, which was a splinter organisation, not a separate party. Menzies, and Senators Leckie and Spicer from Victoria, Cameron, Duncan, Price, Shcey and Senators McLeary, McBride, the McLachlans, Uphill and Wilson from South Australia, Beck and Senator Sampson from Tasmania, Harrison from New South Wales and Senator Collett from Western Australia comprised the group. Spender stood aloof. 1 This disturbed Ward. As a potential leader of the UAP Menzies was likely to be more of an electoral threat to the ALP, than Hughes, well past his prime, and in the eyes of the public a spent political force. Still, he was content to wait for the appropriate moment to discredit his old foe, confident he had the ammunition in his Brisbane Line claims. The Brisbane Line Controversy Ward managed to verify that a plan existed which had intended to abandon all of Australia north of a line north of Brisbane and following a diagonal course to a point north of Adelaide to be abandoned to the enemy, - the Maryborough Plan. -

2016 RMWA Catalogue of Results

2016 CATALOGUE OF RESULTS THE ROYAL AGRICULTURAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA THANKS AND ACKNOWLEDGES THE FOLLOWING SPONSORS PRESENTING PARTNER OF THE AWARDS PRESENTATION TROPHY SPONSORS 2016 Catalogue of Results The Royal Agricultural Society of Victoria Limited ABN 66 006 728 785 ACN 006 728 785 Melbourne Showgrounds Epsom Road Ascot Vale VIC 3032 Telephone +61 3 9281 7444 Facsimile +61 3 9281 7592 www.rasv.com.au List of Office Bearers As at 23/08/2016 Patron Her Excellency the Honourable Linda Dessau AM – Governor of Victoria Board of Directors M. J. Coleman (Chair) D. S. Chapman D. Grimsey A. J. Hawkes N. E. King OAM J. A. Potter P. J. B. Ronald OAM S. C. Spargo AM Chairman M. J. Coleman Chief Executive Officer M. O’Sullivan Company Secretary J. Perry Organising Committee Angie Bradbury (Chair) Tom Carson (Chair of Judges) David Bicknell Chris Crawford Matt Harrop Samantha Isherwood Gabrielle Poy Matt Skinner Nick Stock Event Manager, Beverage Damian Nieuwesteeg Telephone: +61 3 9281 7461 Email: [email protected] Contents CEO’s Message 3 Chair of Judges’ Report 5 Judges’ Biographies 6 2016 Major Trophy Winners 14 2016 Trophy Winners 18 2016 Report on Entries 20 Past Jimmy Watson Memorial Trophy Winners 21 2016 Results 23 Best Vermouth Best Sparkling Best Riesling Best Chardonnay Best Semillon Best Sauvignon Blanc or Blend of Semillon & Sauvignon Blanc Best Single Varietal White Best White Blend Best Sweet White Wine Best Rosé Best Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot or Blend of Bordeaux Varieties Best Single Varietal Red Best Grenache, Red Rhone Varietal or Blend of Red Rhone Varieties Best Shiraz/Cabernet Blend Best Red Blend Best Mature Wine Best Fortified Best Organic or Biodynamic Wine Victorian Wines of Provenance Exhibitors List 104 Royal Melbourne 2 Wine Awards CEO’s Message MARK O’SULLIVAN RASV CEO The Royal Agricultural Society of Victoria (RASV) is delighted to present the winners of the 2016 Royal Melbourne Wine Awards (RMWA), Australia’s most respected wine show, recognising and rewarding excellence in Australian winemaking. -

Publications for David Clune 2020 2019 2018

Publications for David Clune 2020 Clune, D., Smith, R. (2019). Back to the 1950s: the 2019 NSW Clune, D. (2020), 'Warm, Dry and Green': release of the 1989 Election. Australasian Parliamentary Review, 34(1), 86-101. <a Cabinet papers, NSW State Archives and Records Office, 2020. href="http://dx.doi.org/10.3316/informit.950846227656871">[ More Information]</a> Clune, D. (2020). A long history of political corruption in NSW: and the downfall of MPs, ministers and premiers. The Clune, D. (2019). Big-spending blues. Inside Story. <a Conversation. <a href="https://theconversation.com/the-long- href="https://insidestory.org.au/big-spending-blues/">[More history-of-political-corruption-in-nsw-and-the-downfall-of-mps- Information]</a> ministers-and-premiers-147994">[More Information]</a> Clune, D. (2019). Book Review. The Hilton bombing: Evan Clune, D. (2020). Book review: 'Dead Man Walking: The Pederick and the Ananda Marga. Australasian Parliamentary Murky World of Michael McGurk and Ron Medich, by Kate Review, 34(1). McClymont with Vanda Carson. Melbourne: Vintage Australia, Clune, D. (2019). Book Review: "Run for your Life" by Bob 2019. Australasian Parliamentary Review, 34(2), 147-148. <a Carr. Australian Journal of Politics and History, 65(1), 146- href="https://www.aspg.org.au/wp- 147. <a href="http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ajph.12549">[More content/uploads/2020/06/Book-Review-Dead-Man- Information]</a> Walking.pdf">[More Information]</a> Clune, D. (2019). Close enough could be good enough. Inside Clune, D. (2020). Book review: 'The Fatal Lure of Politics: The Story. <a href="https://insidestory.org.au/close-enough-could- Life and Thought of Vere Gordon Childe', by Terry Irving. -

Provenance of Australian Food Products: Is There a Place for Geographical Indications?

Provenance of Australian food products: is there a place for Geographical Indications? By William van Caenegem, Peter Drahos and Jen Cleary Provenance of Australian food products: is there a place for Geographical Indications? by William van Caenegem, Peter Drahos and Jen Cleary July 2015 RIRDC Publication No 15/060 RIRDC Project No PRJ-009251 © 2015 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-74254-806-7 ISSN 1440-6845 Provenance of Australian food products: is there a place for Geographical Indications? Publication No. 15/060 Project No. PRJ-009251 The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC), the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person, arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission, or for any consequences of any such act or omission, made in reliance on the contents of this publication, whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, RIRDC, the authors or contributors. The Commonwealth of Australia does not necessarily endorse the views in this publication. -

The Law at War 1914 – 1915

The Law at War 1914 – 1915 Engaged to Act on Another Front A Working Paper describing the actions of Members of the New South Wales Legal Profession on Gallipoli Tony Cunneen BA MA Dip Ed [email protected] Acknowledgements As with any writing project there are a multitude of people who have assisted with the research. My thanks go to Sir Laurence Street, Peter Marinovic of the Red Cross archives, , The Forbes Society for Legal History, the staff at Willoughby Library who cheerfully tracked down the most obscure books and theses with great patience Introduction Legal history is not simply the accumulation of cases, decisions and statutes. Around this framework swirl the private lives of the solicitors, barristers, judges, clerks and associated professionals who worked in the law. A profession gains part of its character from the private lives and experiences of its early members. Through its professional ancestors the New South Wales legal fraternity is connected to a range of institutions – everything from sporting groups, schools, universities and churches. One significant group has been the military. In World War One all of these eleemnet came togher. Men who had been at the same school, worshipped at teh samechruch, 2 shared the space at the law courts, walked the corridors of chambers, had garden parties overlooking the harbour and caught the same trams and ferries home found themselves next to one another in strange exotic fields when the bullets flew and ordinary soldiers looked to the privileged officers for leadership. While the battles raged, in Australia the mothers, wives an sisters of the soldiers gave countless hours to preparing packages for their menfolk, or organising fundraising, or tracking done details of their fates. -

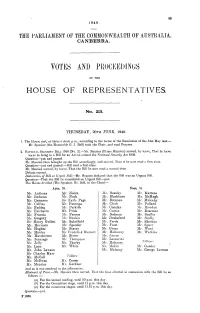

Votes And) Pi{Q0ceei)I Dngs

.1940. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF A1JSTRNLIA, CANBERRA. VOTES AND) PI{Q0CEEI)IDNGS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. No. 23. THURSDAY, 20TH JUNE, 1940. 1. The Hlouse miet, ait three o'clock p.m., according to the terms of the Resolution of the 31st May last.- Mi'. Speaker (the Honorable Or. J. Bell) took the Chair, and read Prayers. 2. NATIONAL SECURITY' BILL 1940 [No. 2].-Mr. Menzies (Prime Minister) moved, by leave, That he have leave to bring in a Bill for an Act to amend the National Secarity Act 1939. Question-put and passed. Mr. Menzies then brought up the Bill accordingly, and moved, That it be now read a first timie. Question-])ut and passed .- Bill read a first time. Mr. Menzies moved, by leave, That the Bill be now read a second timie. Debate ensued. Declaration of Bill as Urgent Bill.-Mr. Asenzies declared that the B1ill was an Urgent Bill. Question-That the B3ill he considered an Urgent Bill-pt. The House divided (The Speaker, Mr. Bell, in the Chair)- Ayes, 39. Noes, 31. M i . Anthony Mr. Nairn Beasley Mi'. Martens Mr. Badmnan Mr. Nock Mr'. Blackburn *Mr'. McHugh Mi'. Cameron Sir' Ear'le Page M r. Brennan Mr'. Mfulcahy M r. Collins Mr'. Paterson Clar k Mi' Pollard Conelan Mr. Rior'dan Mir. Fadden MI'. Perkii'% Mr. Mr. Fairbairn Mi' . Price Curtin A--Ir. Rlosevear Mri . Francis M.Prowse Mr'. Dedm an M~r. Scullin MALr. Gregory Ri.iankiin Mr. iDrakeford Mr'. Scully Sir Henry Gullett Mr'. Seliolfield Forde Mr. Sheehan Frost Mr. -

Ten Journeys to Cameron's Farm

Ten Journeys to Cameron’s Farm An Australian Tragedy Ten Journeys to Cameron’s Farm An Australian Tragedy Cameron Hazlehurst Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Hazlehurst, Cameron, 1941- author. Title: Ten Journeys to Cameron’s Farm / Cameron Hazlehurst. ISBN: 9781925021004 (paperback) 9781925021011 (ebook) Subjects: Menzies, Robert, Sir, 1894-1978. Aircraft accidents--Australian Capital Territory--Canberra. World War, 1939-1945--Australia--History. Australia--Politics and government--1901-1945. Australia--Biography. Australia--History--1901-1945. Dewey Number: 320.994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press © Flaxton Mill House Pty Ltd 2013 and 2015 Cover design and layout © 2013 ANU E Press Cover design and layout © 2015 ANU Press Contents Part 1 Prologue 13 August 1940 . ix 1 . Augury . 1 2 . Leadership, politics, and war . 3 Part 2 The Journeys 3 . A crew assembles: Charlie Crosdale and Jack Palmer . 29 4 . Second seat: Dick Wiesener . 53 5 . His father’s son: Bob Hitchcock . 71 6 . ‘A very sound pilot’?: Bob Hitchcock (II) . 99 7 . Passenger complement . 131 8 . The General: Brudenell White (I) . 139 9 . Call and recall: Brudenell White (II) . 161 10 . The Brigadier: Geoff Street . 187 11 . -

Earle Page and the Imagining of Australia

‘NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT’ EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA ‘NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT’ EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA STEPHEN WILKS Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, Or what’s a heaven for? Robert Browning, ‘Andrea del Sarto’ The man who makes no mistakes does not usually make anything. Edward John Phelps Earle Page as seen by L.F. Reynolds in Table Talk, 21 October 1926. Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760463670 ISBN (online): 9781760463687 WorldCat (print): 1198529303 WorldCat (online): 1198529152 DOI: 10.22459/NPM.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This publication was awarded a College of Arts and Social Sciences PhD Publication Prize in 2018. The prize contributes to the cost of professional copyediting. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: Earle Page strikes a pose in early Canberra. Mildenhall Collection, NAA, A3560, 6053, undated. This edition © 2020 ANU Press CONTENTS Illustrations . ix Acknowledgements . xi Abbreviations . xiii Prologue: ‘How Many Germans Did You Kill, Doc?’ . xv Introduction: ‘A Dreamer of Dreams’ . 1 1 . Family, Community and Methodism: The Forging of Page’s World View . .. 17 2 . ‘We Were Determined to Use Our Opportunities to the Full’: Page’s Rise to National Prominence . -

Part 4 Australia Today

Australia today In these pages you will learn about what makes this country so special. You will find out more about our culture, Part 4 our innovators and our national identity. In the world today, Australia is a dynamic business and trade partner and a respected global citizen. We value the contribution of new migrants to our country’s constant growth and renewal. Australia today The land Australia is unique in many ways. Of the world’s seven continents, Australia is the only one to be occupied by a single nation. We have the lowest population density in the world, with only two people per square kilometre. Australia is one of the world’s oldest land masses. It is the sixth largest country in the world. It is also the driest inhabited continent, so in most parts of Australia water is a very precious resource. Much of the land has poor soil, with only 6 per cent suitable for agriculture. The dry inland areas are called ‘the Australia is one of the world’s oldest land masses. outback’. There is great respect for people who live and work in these remote and harsh environments. Many of It is the sixth largest country in the world. them have become part of Australian folklore. Because Australia is such a large country, the climate varies in different parts of the continent. There are tropical regions in the north of Australia and deserts in the centre. Further south, the temperatures can change from cool winters with mountain snow, to heatwaves in summer. In addition to the six states and two mainland territories, the Australian Government also administers, as territories, Ashmore and Cartier Islands, Christmas Island, the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, Jervis Bay Territory, the Coral Sea Islands, Heard Island and McDonald Islands in the Australian Antarctic Territory, and Norfolk Island. -

Earle Page: an Active Treasurer

Earle Page: an active treasurer John Hawkins1 Earle Christmas Grafton Page brought down six Budgets while serving as Bruce’s treasurer. He was fortunate in when he was treasurer, after the war and before the Depression, which allowed him to ease tax burdens. Bruce and Page established the Loan Council and the National Debt Sinking Fund and introduced ‘tied grants’ to the States. Page moved the Commonwealth Bank further towards being a central bank and gave it responsibility for the note issue. Source: National Library of Australia 1 The author was formerly in Domestic Economy Division, the Australian Treasury. This article has benefited from discussions with Selwyn Cornish and the assistance of the Reserve Bank archivists. The views in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Australian Treasury. 55 Earle Page: an active treasurer Introduction As well as being a long-serving treasurer, Sir Earle Page PC GCMG served as prime minister for 20 days and was often acting prime minister. Only Billy Hughes has served a longer term in the House of Representatives. But as well as possessing longevity, Page was also innovative. His private secretary recalls him as ‘a combination of dreaming idealist and intensely practical man of affairs’.2 Indeed, he was described as ‘energetic, almost incoherent as he poured out ideas faster than words would come in an orderly fashion’, peppered with his trademark ‘you see, you see’.3 He not only had a lot of energy for his ideas and his politics. Physically robust, Page played a daily hard game of tennis until he was over 80, and ‘he played it as he played the political game, with reckless energy, native cunning and a certain contempt for the orthodox rules of the game’.4 His energy was accompanied by an ability to get on well with most of his colleagues.