Competition and Mimicry: the Curious Case of Chaetae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Sponge Evolution: a Review and Phylogenetic Framework

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Palaeoworld 27 (2018) 1–29 Review Early sponge evolution: A review and phylogenetic framework a,b,∗ a Joseph P. Botting , Lucy A. Muir a Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 39 East Beijing Road, Nanjing 210008, China b Department of Natural Sciences, Amgueddfa Cymru — National Museum Wales, Cathays Park, Cardiff CF10 3LP, UK Received 27 January 2017; received in revised form 12 May 2017; accepted 5 July 2017 Available online 13 July 2017 Abstract Sponges are one of the critical groups in understanding the early evolution of animals. Traditional views of these relationships are currently being challenged by molecular data, but the debate has so far made little use of recent palaeontological advances that provide an independent perspective on deep sponge evolution. This review summarises the available information, particularly where the fossil record reveals extinct character combinations that directly impinge on our understanding of high-level relationships and evolutionary origins. An evolutionary outline is proposed that includes the major early fossil groups, combining the fossil record with molecular phylogenetics. The key points are as follows. (1) Crown-group sponge classes are difficult to recognise in the fossil record, with the exception of demosponges, the origins of which are now becoming clear. (2) Hexactine spicules were present in the stem lineages of Hexactinellida, Demospongiae, Silicea and probably also Calcarea and Porifera; this spicule type is not diagnostic of hexactinellids in the fossil record. (3) Reticulosans form the stem lineage of Silicea, and probably also Porifera. (4) At least some early-branching groups possessed biminerallic spicules of silica (with axial filament) combined with an outer layer of calcite secreted within an organic sheath. -

Spicule Formation in Calcareous Sponges: Coordinated Expression

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Spicule formation in calcareous sponges: Coordinated expression of biomineralization genes and Received: 17 November 2016 Accepted: 02 March 2017 spicule-type specific genes Published: 13 April 2017 Oliver Voigt1, Maja Adamska2, Marcin Adamski2, André Kittelmann1, Lukardis Wencker1 & Gert Wörheide1,3,4 The ability to form mineral structures under biological control is widespread among animals. In several species, specific proteins have been shown to be involved in biomineralization, but it is uncertain how they influence the shape of the growing biomineral and the resulting skeleton. Calcareous sponges are the only sponges that form calcitic spicules, which, based on the number of rays (actines) are distinguished in diactines, triactines and tetractines. Each actine is formed by only two cells, called sclerocytes. Little is known about biomineralization proteins in calcareous sponges, other than that specific carbonic anhydrases (CAs) have been identified, and that uncharacterized Asx-rich proteins have been isolated from calcitic spicules. By RNA-Seq and RNA in situ hybridization (ISH), we identified five additional biomineralization genes inSycon ciliatum: two bicarbonate transporters (BCTs) and three Asx-rich extracellular matrix proteins (ARPs). We show that these biomineralization genes are expressed in a coordinated pattern during spicule formation. Furthermore, two of the ARPs are spicule- type specific for triactines and tetractines (ARP1 orSciTriactinin ) or diactines (ARP2 or SciDiactinin). Our results suggest that spicule formation is controlled by defined temporal and spatial expression of spicule-type specific sets of biomineralization genes. By the process of biomineralization many animal groups produce mineral structures like skeletons, shells and teeth. Biominerals differ in shape considerably from their inorganic mineral counterparts1. -

Bryozoan Studies 2019

BRYOZOAN STUDIES 2019 Edited by Patrick Wyse Jackson & Kamil Zágoršek Czech Geological Survey 1 BRYOZOAN STUDIES 2019 2 Dedication This volume is dedicated with deep gratitude to Paul Taylor. Throughout his career Paul has worked at the Natural History Museum, London which he joined soon after completing post-doctoral studies in Swansea which in turn followed his completion of a PhD in Durham. Paul’s research interests are polymatic within the sphere of bryozoology – he has studied fossil bryozoans from all of the geological periods, and modern bryozoans from all oceanic basins. His interests include taxonomy, biodiversity, skeletal structure, ecology, evolution, history to name a few subject areas; in fact there are probably none in bryozoology that have not been the subject of his many publications. His office in the Natural History Museum quickly became a magnet for visiting bryozoological colleagues whom he always welcomed: he has always been highly encouraging of the research efforts of others, quick to collaborate, and generous with advice and information. A long-standing member of the International Bryozoology Association, Paul presided over the conference held in Boone in 2007. 3 BRYOZOAN STUDIES 2019 Contents Kamil Zágoršek and Patrick N. Wyse Jackson Foreword ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 Caroline J. Buttler and Paul D. Taylor Review of symbioses between bryozoans and primary and secondary occupants of gastropod -

Nitrogen-Fixing, Photosynthetic, Anaerobic Bacteria Associated with Pelagic Copepods

- AQUATIC MICROBIAL ECOLOGY Vol. 12: 105-113. 1997 Published April 10 , Aquat Microb Ecol Nitrogen-fixing, photosynthetic, anaerobic bacteria associated with pelagic copepods Lita M. Proctor Department of Oceanography, Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida 32306-3048, USA ABSTRACT: Purple sulfur bacteria are photosynthetic, anaerobic microorganisms that fix carbon di- oxide using hydrogen sulfide as an electron donor; many are also nitrogen fixers. Because of the~r requirements for sulfide or orgamc carbon as electron donors in anoxygenic photosynthesis, these bac- teria are generally thought to be lim~tedto shallow, organic-nch, anoxic environments such as subtidal marine sediments. We report here the discovery of nitrogen-fixing, purple sulfur bactena associated with pelagic copepods from the Caribbean Sea. Anaerobic incubations of bacteria associated with fuU- gut and voided-gut copepods resulted in enrichments of purple/red-pigmented purple sulfur bacteria while anaerobic incubations of bacteria associated with fecal pellets did not yield any purple sulfur bacteria, suggesting that the photosynthetic anaerobes were specifically associated with copepods. Pigment analysis of the Caribbean Sea copepod-associated bacterial enrichments demonstrated that these bactena possess bacter~ochlorophylla and carotenoids in the okenone series, confirming that these bacteria are purple sulfur bacteria. Increases in acetylene reduction paralleled the growth of pur- ple sulfur bactena in the copepod ennchments, suggesting that the purple sulfur bacteria are active nitrogen fixers. The association of these bacteria with planktonic copepods suggests a previously unrecognized role for photosynthetic anaerobes in the marine S, N and C cycles, even in the aerobic water column of the open ocean. KEY WORDS: Manne purple sulfur bacterla . -

The Anti-Viral Applications of Marine Resources for COVID-19 Treatment: an Overview

marine drugs Review The Anti-Viral Applications of Marine Resources for COVID-19 Treatment: An Overview Sarah Geahchan 1,2, Hermann Ehrlich 1,3,4,5 and M. Azizur Rahman 1,3,* 1 Centre for Climate Change Research, Toronto, ON M4P 1J4, Canada; [email protected] (S.G.); [email protected] (H.E.) 2 Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON M5S 2E8, Canada 3 A.R. Environmental Solutions, University of Toronto, ICUBE-UTM, Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6, Canada 4 Institute of Electronic and Sensor Materials, TU Bergakademie Freiberg, 09599 Freiberg, Germany 5 Center for Advanced Technology, Adam Mickiewicz University, 61614 Poznan, Poland * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The ongoing pandemic has led to an urgent need for novel drug discovery and potential therapeutics for Sars-CoV-2 infected patients. Although Remdesivir and the anti-inflammatory agent dexamethasone are currently on the market for treatment, Remdesivir lacks full efficacy and thus, more drugs are needed. This review was conducted through literature search of PubMed, MDPI, Google Scholar and Scopus. Upon review of existing literature, it is evident that marine organisms harbor numerous active metabolites with anti-viral properties that serve as potential leads for COVID- 19 therapy. Inorganic polyphosphates (polyP) naturally found in marine bacteria and sponges have been shown to prevent viral entry, induce the innate immune response, and downregulate human ACE-2. Furthermore, several marine metabolites isolated from diverse sponges and algae have been shown to inhibit main protease (Mpro), a crucial protein required for the viral life cycle. Sulfated polysaccharides have also been shown to have potent anti-viral effects due to their anionic properties and high molecular weight. -

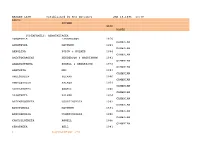

BRAGEN LIST Established by Rex Doescher JAN 19,1996 13:38 GENUS AUTHOR DATE RANGE

BRAGEN LIST established by Rex Doescher JAN 19,1996 13:38 GENUS AUTHOR DATE RANGE SUPERFAMILY: ACROTRETACEA ACROTHELE LINNARSSON 1876 CAMBRIAN ACROTHYRA MATTHEW 1901 CAMBRIAN AKMOLINA POPOV & HOLMER 1994 CAMBRIAN AMICTOCRACENS HENDERSON & MACKINNON 1981 CAMBRIAN ANABOLOTRETA ROWELL & HENDERSON 1978 CAMBRIAN ANATRETA MEI 1993 CAMBRIAN ANELOTRETA PELMAN 1986 CAMBRIAN ANGULOTRETA PALMER 1954 CAMBRIAN APHELOTRETA ROWELL 1980 CAMBRIAN APSOTRETA PALMER 1954 CAMBRIAN BATENEVOTRETA USHATINSKAIA 1992 CAMBRIAN BOTSFORDIA MATTHEW 1891 CAMBRIAN BOZSHAKOLIA USHATINSKAIA 1986 CAMBRIAN CANTHYLOTRETA ROWELL 1966 CAMBRIAN CERATRETA BELL 1941 1 Range BRAGEN LIST - 1996 CAMBRIAN CURTICIA WALCOTT 1905 CAMBRIAN DACTYLOTRETA ROWELL & HENDERSON 1978 CAMBRIAN DEARBORNIA WALCOTT 1908 CAMBRIAN DIANDONGIA RONG 1974 CAMBRIAN DICONDYLOTRETA MEI 1993 CAMBRIAN DISCINOLEPIS WAAGEN 1885 CAMBRIAN DISCINOPSIS MATTHEW 1892 CAMBRIAN EDREJA KONEVA 1979 CAMBRIAN EOSCAPHELASMA KONEVA & AL 1990 CAMBRIAN EOTHELE ROWELL 1980 CAMBRIAN ERBOTRETA HOLMER & USHATINSKAIA 1994 CAMBRIAN GALINELLA POPOV & HOLMER 1994 CAMBRIAN GLYPTACROTHELE TERMIER & TERMIER 1974 CAMBRIAN GLYPTIAS WALCOTT 1901 CAMBRIAN HADROTRETA ROWELL 1966 CAMBRIAN HOMOTRETA BELL 1941 CAMBRIAN KARATHELE KONEVA 1986 CAMBRIAN KLEITHRIATRETA ROBERTS 1990 CAMBRIAN 2 Range BRAGEN LIST - 1996 KOTUJOTRETA USHATINSKAIA 1994 CAMBRIAN KOTYLOTRETA KONEVA 1990 CAMBRIAN LAKHMINA OEHLERT 1887 CAMBRIAN LINNARSSONELLA WALCOTT 1902 CAMBRIAN LINNARSSONIA WALCOTT 1885 CAMBRIAN LONGIPEGMA POPOV & HOLMER 1994 CAMBRIAN LUHOTRETA MERGL & SLEHOFEROVA -

Comprehensive Review of Cambrian Himalayan

http://www.diva-portal.org Postprint This is the accepted version of a paper published in Papers in Palaeontology. This paper has been peer- reviewed but does not include the final publisher proof-corrections or journal pagination. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Popov, L E., Holmer, L E., Hughes, N C., Ghobadi Pour, M., Myrow, P M. (2015) Himalayan Cambrian brachiopods. Papers in Palaeontology, 1(4): 345-399 http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/spp2.1017 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-255813 HIMALAYAN CAMBRIAN BRACHIOPODS BY LEONID E. POPOV1, LARS E. HOLMER2, NIGEL C. HUGHES3 MANSOUREH GHOBADI POUR4 AND PAUL M. MYROW5 1Department of Geology, National Museum of Wales, Cathays Park, Cardiff CF10 3NP, United Kingdom, <[email protected]>; 2Institute of Earth Sciences, Palaeobiology, Uppsala University, SE-752 36 Uppsala, Sweden, <[email protected]>; 3Department of Earth Sciences, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521, USA <[email protected]>; 4Department of Geology, Faculty of Sciences, Golestan University, Gorgan, Iran and Department of Geology, National Museum of Wales, Cathays Park, Cardiff CF10 3NP, United Kingdom <[email protected]>; 5 Department of Geology, Colorado College, Colorado Springs, CO 80903, USA <[email protected]> Abstract: A synoptic analysis of previously published material and new finds reveals that Himalayan Cambrian brachiopods can be referred to 18 genera, of which 17 are considered herein. These contain 20 taxa assigned to species, of which five are new: Eohadrotreta haydeni, Aphalotreta khemangarensis, Hadrotreta timchristiorum, Prototreta? sumnaensis and Amictocracens? brocki. -

DOGAMI Open-File Report O-86-06, the State of Scientific

"ABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ..~**********..~...~*~~.~...~~~~1 GORDA RIDGE LEASE AREA ....................... 2 RELATED STUDIES IN THE NORTH PACIFIC .+,...,. 5 BYDROTHERMAL TEXTS ........................... 9 34T.4 GAPS ................................... r6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ............................. I8 APPENDIX 1. Species found on the Gorda Ridge or within the lease area . .. .. .. .. .. 36 RPPENDiX 2. Species found outside the lease area that may occur in the Gorda Ridge Lease area, including hydrothermal vent organisms .................................55 BENTHOS THE STATE OF SCIENTIFIC INFORMATION RELATING TO THE BIOLOGY AND ECOLOGY 3F THE GOUDA RIDGE STUDY AREA, NORTZEAST PACIFIC OCEAN: INTRODUCTION Presently, only two published studies discuss the ecology of benthic animals on the Gorda Sidge. Fowler and Kulm (19701, in a predominantly geolgg isal study, used the presence of sublittor31 and planktsnic foraminiferans as an indication of uplift of tfie deep-sea fioor. Their resuits showed tiac sedinenta ana foraminiferans are depositea in the Zscanaba Trough, in the southern part of the Corda Ridge, by turbidity currents with a continental origin. They list 22 species of fararniniferans from the Gorda Rise (See Appendix 13. A more recent study collected geophysical, geological, and biological data from the Gorda Ridge, with particular emphasis on the northern part of the Ridge (Clague et al. 19843. Geological data suggest the presence of widespread low-temperature hydrothermal activity along the axf s of the northern two-thirds of the Corda 3idge. However, the relative age of these vents, their present activity and presence of sulfide deposits are currently unknown. The biological data, again with an emphasis on foraminiferans, indicate relatively high species diversity and high density , perhaps assoc iated with widespread hydrotheraal activity. -

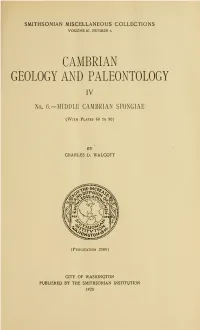

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections

SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 67, NUMBER 6 CAMBRIAN GEOLOGY AND PALEONTOLOGY IV No. 6.—MIDDLE CAMBRIAN SPONGIAE (With Plates 60 to 90) BY CHARLES D. WALCOTT (Publication 2580) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION 1920 Z$t Bovb Qgattimote (press BALTIMORE, MD., U. S. A. CAMBRIAN GEOLOGY AND PALEONTOLOGY IV No. 6.—MIDDLE CAMBRIAN SPONGIAE By CHARLES D. WALCOTT (With Plates 60 to 90) CONTENTS PAGE Introduction 263 Habitat = 265 Genera and species 265 Comparison with recent sponges 267 Comparison with Metis shale sponge fauna 267 Description of species 269 Sub-Class Silicispongiae 269 Order Monactinellida Zittel (Monaxonidae Sollas) 269 Sub-Order Halichondrina Vosmaer 269 Halichondrites Dawson 269 Halichondrites elissa, new species 270 Tuponia, new genus 271 Tuponia lineata, new species 272 Tuponia bellilineata, new species 274 Tuponia flexilis, new species 275 Tuponia flexilis var. intermedia, new variety 276 Takakkawia, new genus 277 Takakkawia lineata, new species 277 Wapkia, new genus 279 Wapkia grandis, new species 279 Hazelia, new genus 281 Hazelia palmata, new species 282 Hazelia conf erta, new species 283 Hazelia delicatula, new species 284 Hazelia ? grandis, new species 285. Hazelia mammillata, new species 286' Hazelia nodulifera, new species 287 Hazelia obscura, new species 287 Corralia, new genus 288 Corralia undulata, new species 288 Sentinelia, new genus 289 Sentinelia draco, new species 290 Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, Vol. 67, No. 6 261 262 SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOL. 6j Family Suberitidae 291 Choia, new genus 291 Choia carteri, new species 292 Choia ridleyi, new species 294 Choia utahensis, new species 295 Choia hindei (Dawson) 295 Hamptonia, new genus 296 Hamptonia bowerbanki, new species 297 Pirania, new genus 298 Pirania muricata, new species 298 Order Hexactinellida O. -

H1.1 Open Water

PAGE .............................................................. 392 ▼ H1.1 OPEN WATER The open-water offshore habitat covers an area of by which solar energy enters the marine ecosystem, Nova Scotia larger than the land mass, and includes similar to the layer of plants on land. The ocean H1.1 Open Water salt water in inlets, bays and estuaries. The water waters are distinctive in having fostered the origins and the organisms it supports are the primary means of life on the planet. Plate H1.1.1: Right Whale, north of Brier Island (Unit 912). Photo: BIOS Habitats Natural History of Nova Scotia, Volume I © Nova Scotia Museum of Natural History .............................................................. PAGE 393 ▼ FORMATION PLANTS Oceans are formed as part of major geological events. The plants of the open ocean are almost entirely Nova Scotia’s open-ocean habitats are part of the microscopic algae, collectively known as phyto- Atlantic Ocean, which opened during the Jurassic plankton. Many different species occur, including Period and has been in continuous existence ever representatives of the prochlorophytes (blue-green since. The quality and depth of the water column algae—evolutionary intermediates between bacteria have fluctuated in relation to post-glacial climatic and algae), diatoms, dinoflagellates, chrysomonads, conditions. cryptomonads, minute flagellates and unicellular reproductive stages of macroscopic algae. Phyto- H1.1 PHYSICAL ASPECTS plankton are often grouped in size classes: Open Water 1. Water conditions, such as salinity, temperature, macroplankton: 200–2000 micrometres, includes ice-formation, turbidity, light penetration, tides larger diatoms. and currents, are extremely variable in the microplankton: 20–200 micrometres, includes waters offshore. most diatoms. 2. Air-water interaction, surface-water turbulence nanoplankton: 2–20 micrometres, includes determines the level of wave and gas exchange. -

OREGON ESTUARINE INVERTEBRATES an Illustrated Guide to the Common and Important Invertebrate Animals

OREGON ESTUARINE INVERTEBRATES An Illustrated Guide to the Common and Important Invertebrate Animals By Paul Rudy, Jr. Lynn Hay Rudy Oregon Institute of Marine Biology University of Oregon Charleston, Oregon 97420 Contract No. 79-111 Project Officer Jay F. Watson U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 500 N.E. Multnomah Street Portland, Oregon 97232 Performed for National Coastal Ecosystems Team Office of Biological Services Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Department of Interior Washington, D.C. 20240 Table of Contents Introduction CNIDARIA Hydrozoa Aequorea aequorea ................................................................ 6 Obelia longissima .................................................................. 8 Polyorchis penicillatus 10 Tubularia crocea ................................................................. 12 Anthozoa Anthopleura artemisia ................................. 14 Anthopleura elegantissima .................................................. 16 Haliplanella luciae .................................................................. 18 Nematostella vectensis ......................................................... 20 Metridium senile .................................................................... 22 NEMERTEA Amphiporus imparispinosus ................................................ 24 Carinoma mutabilis ................................................................ 26 Cerebratulus californiensis .................................................. 28 Lineus ruber ......................................................................... -

The Weeks Formation Konservat-Lagerstätte and the Evolutionary Transition of Cambrian Marine Life

Downloaded from http://jgs.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on October 1, 2021 Review focus Journal of the Geological Society Published Online First https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs2018-042 The Weeks Formation Konservat-Lagerstätte and the evolutionary transition of Cambrian marine life Rudy Lerosey-Aubril1*, Robert R. Gaines2, Thomas A. Hegna3, Javier Ortega-Hernández4,5, Peter Van Roy6, Carlo Kier7 & Enrico Bonino7 1 Palaeoscience Research Centre, School of Environmental and Rural Science, University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351, Australia 2 Geology Department, Pomona College, Claremont, CA 91711, USA 3 Department of Geology, Western Illinois University, 113 Tillman Hall, 1 University Circle, Macomb, IL 61455, USA 4 Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3EJ, UK 5 Museum of Comparative Zoology and Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, 26 Oxford Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 6 Department of Geology, Ghent University, Krijgslaan 281/S8, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium 7 Back to the Past Museum, Carretera Cancún, Puerto Morelos, Quintana Roo 77580, Mexico R.L.-A., 0000-0003-2256-1872; R.R.G., 0000-0002-3713-5764; T.A.H., 0000-0001-9067-8787; J.O.-H., 0000-0002- 6801-7373 * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The Weeks Formation in Utah is the youngest (c. 499 Ma) and least studied Cambrian Lagerstätte of the western USA. It preserves a diverse, exceptionally preserved fauna that inhabited a relatively deep water environment at the offshore margin of a carbonate platform, resembling the setting of the underlying Wheeler and Marjum formations. However, the Weeks fauna differs significantly in composition from the other remarkable biotas of the Cambrian Series 3 of Utah, suggesting a significant Guzhangian faunal restructuring.