Evidence of Submitter Zane Moss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KINGSTON Community Response Plan Contents

KINGSTON Community Response Plan contents... get ready... Kingston Area Map 3 Road Transport Crashes 21 KINGSTON Before, during and after 21 Truck crash zones maps 22 Key Hazards 4 Area Map Earthquake 4 Major Storms / Snowstorms 4 Kingston Township 6 Flood 4 Evacuation Routes 23 Wildfire 4 Landslide 5 Accident 5 Kingston Evacuation Routes 24 Household Emergency Plan 6 Garston Evacuation Routes 25 Emergency Survival Kit 7 Getaway Kit 7 Plan Activation Process 26 Roles and responsibilities 26 Stay in touch 7 6 Civil Defence Centres 27 Earthquake 8 KINGSTON Before and during an earthquake 8 Vulnerable Population Site 28 After an earthquake 9 Post disaster building management 9 Kingston 6 Tactical Sites Map 29 & 30 Major Storms / Snowstorms 11 Garston Before and when a warning is issued 11 Tactical Sites Map 31 After a storm, snowstorms 12 Kingston Flood 13 Civil Defence Centres Map 32 Before, during and after 13 Lake & River level 14 Lake Wakatipu Flood map 15 Garston Upper Mataura Flood map 16 Civil Defence Centres Map 33 6 GARSTON Wildfires 17 Visitor, Tourist and Before and during 17 Foreign National Welfare 34 After a fire 18 Fire seasons 18 Emergency Contacts 35 Landslide 19 Before and during 19 Notes 36 After a landslide 20 6 Danger signs 20 NOKOMAI For further information 40 2 3 get ready... get ready... Flooding THE KEY HAZARDS IN KINGSTON Floods can cause injury and loss of life, • the floods have risen very quickly Earthquake // Major Storms // Snowstorms damage to property and infrastructure, loss of • the floodwater contains debris, such as trees stock, and contamination of water and land. -

Ïg8g - 1Gg0 ISSN 0113-2S04

MAF $outtr lsland *nanga spawning sur\feys, ïg8g - 1gg0 ISSN 0113-2s04 New Zealand tr'reshwater Fisheries Report No. 133 South Island inanga spawning surv€ys, 1988 - 1990 by M.J. Taylor A.R. Buckland* G.R. Kelly * Department of Conservation hivate Bag Hokitika Report to: Department of Conservation Freshwater Fisheries Centre MAF Fisheries Christchurch Servicing freshwater fisheries and aquaculture March L992 NEW ZEALAND F'RESTTWATER F'ISHERIES RBPORTS This report is one of a series issued by the Freshwater Fisheries Centre, MAF Fisheries. The series is issued under the following criteria: (1) Copies are issued free only to organisations which have commissioned the investigation reported on. They will be issued to other organisations on request. A schedule of reports and their costs is available from the librarian. (2) Organisations may apply to the librarian to be put on the mailing list to receive all reports as they are published. An invoice will be sent for each new publication. ., rsBN o-417-O8ffi4-7 Edited by: S.F. Davis The studies documented in this report have been funded by the Department of Conservation. MINISTBY OF AGRICULTUBE AND FISHERIES TE MANAlU AHUWHENUA AHUMOANA MAF Fisheries is the fisheries business group of the New Zealand Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries. The name MAF Fisheries was formalised on I November 1989 and replaces MAFFish, which was established on 1 April 1987. It combines the functions of the t-ormer Fisheries Research and Fisheries Management Divisions, and the fisheries functions of the former Economics Division. T\e New Zealand Freshwater Fisheries Report series continues the New Zealand Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, Fisheries Environmental Report series. -

The Whitestone River by Jr Mills

THE WHITESTONE RIVER BY J.R. MILLS Mills, John (1989) The Whitestone River -- Mills, John (1989) The Whitestone river , . ' . ' . .. _ ' . THE WHITESTONE RIVER John R Mills ---00000--- October 1989 Cover Photo Whitestone River looking upstream towards State Highway 94 bridge and Livingstone Mountain in the background. I. CONTENTS Page number Introduction III Objective ill List of photographs and maps IV Chapter 1 River Description and Location 1.1 Topography 1 1.2 Climate 1 1.3 Vegetation 3 1.4 Soils 3 1.5 Erosion 3 1.6 Water 4 Chapter 2 A Recent History and Factors that have Contributed to the River's Change 6 Chapter 3 Present use and Policy 3.1 Gravel Extraction 8 3.2 Water Rights 8 3.3 Angling 8 3.3a Fishery Requirements 9 3.4 Picnicking 9 3.5 Water Fowl Hunting 9 Chapter 4 Potential Uses 4.1 Grazing 10 4.2 Hay Cutting 10 4.3 Tree Planting 10 Chapter 5 The Public Debate 12 Chapter 6 Man's Interaction with Nature In terms of land development, berm management and their effects on the Whitestone River. 6.1 Scope of Land Development 29 6.2 Berm Boundaries 31 6.3 River Meanders 36 6.4 Protective Planting 39 6.5 Rock and Groyne Works 39 II. Chapter 7 Submissions from Interested Parties 7.1 Southland Catchment Board 42 7.2 Southland Acclimatisation Society 46 - Whitestone River Management and its Trout Fisheries 46 - Submission Appendix Whitestone River Comparison Fisheries Habitat 51 7.3 Farmers Adjoining the River 56 Chapter 8 Options for Future Ownership and Management of the River 57 Chapter 9 Recommendations and Conclusions 9.1a Financial Restraints 59 9.1 b Berm Boundary Constraints 59 9.2 Management Practices 59 9.3 Independent Study 60 9.4 Consultation 60 9.5 Rating 61 9.6 Finally 61 Chapter 10 Recommendations 62 Chapter 11 Acknowledgements 63 ---00000--- III. -

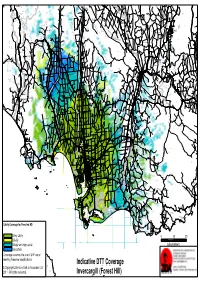

Indicative DTT Coverage Invercargill (Forest Hill)

Blackmount Caroline Balfour Waipounamu Kingston Crossing Greenvale Avondale Wendon Caroline Valley Glenure Kelso Riversdale Crossans Corner Dipton Waikaka Chatton North Beaumont Pyramid Tapanui Merino Downs Kaweku Koni Glenkenich Fleming Otama Mt Linton Rongahere Ohai Chatton East Birchwood Opio Chatton Maitland Waikoikoi Motumote Tua Mandeville Nightcaps Benmore Pomahaka Otahu Otamita Knapdale Rankleburn Eastern Bush Pukemutu Waikaka Valley Wharetoa Wairio Kauana Wreys Bush Dunearn Lill Burn Valley Feldwick Croydon Conical Hill Howe Benio Otapiri Gorge Woodlaw Centre Bush Otapiri Whiterigg South Hillend McNab Clifden Limehills Lora Gorge Croydon Bush Popotunoa Scotts Gap Gordon Otikerama Heenans Corner Pukerau Orawia Aparima Waipahi Upper Charlton Gore Merrivale Arthurton Heddon Bush South Gore Lady Barkly Alton Valley Pukemaori Bayswater Gore Saleyards Taumata Waikouro Waimumu Wairuna Raymonds Gap Hokonui Ashley Charlton Oreti Plains Kaiwera Gladfield Pikopiko Winton Browns Drummond Happy Valley Five Roads Otautau Ferndale Tuatapere Gap Road Waitane Clinton Te Tipua Otaraia Kuriwao Waiwera Papatotara Forest Hill Springhills Mataura Ringway Thomsons Crossing Glencoe Hedgehope Pebbly Hills Te Tua Lochiel Isla Bank Waikana Northope Forest Hill Te Waewae Fairfax Pourakino Valley Tuturau Otahuti Gropers Bush Tussock Creek Waiarikiki Wilsons Crossing Brydone Spar Bush Ermedale Ryal Bush Ota Creek Waihoaka Hazletts Taramoa Mabel Bush Flints Bush Grove Bush Mimihau Thornbury Oporo Branxholme Edendale Dacre Oware Orepuki Waimatuku Gummies Bush -

Catlins Catl

Fishing the Catlins Fishing in the Catlins Surrounded by remote rainforest and rolling hill country, anglers seeking solitude and scenery will find the streams of the Catlins rewarding. With consistently high annual rainfall and plenty of valley systems, anglers following the Southern Scenic Route between Balclutha and Footrose will discover numerous waterways to explore. All of the significant streams and rivers hold good populations of resident brown trout between 1-2 kg, and in their lower reaches sea-run brown trout which can reach 3-4kg. Owaka river entering the Catlins Lake Most streams originate in rainforest or tussock swamplands (giving the water noticeable to fish) and hurl it into a likely looking hole. Some experienced local potential. Containing lots of baitfish and crabs the trout are normally in a tea stained coloration) and flow through forest and farmland before entering anglers fish with smelt and bullies which can be irresistible to large trout, especially good condition and excellent eating. Often the best fishing areas are close to a tidal zone and then the Pacific Ocean. Anglers should adjust their fishing at night or the change of light. structure such as reefs and logs and near deep holes and drop offs. During methods depending on whether they are fishing in the estuary/lower, or upper the spring and summer months, evening and night fishing and can be very reaches of a river. Fly anglers should try baitfish imitations such as Mrs Simpson (red), Parsons productive (especially off the Hina Hina Road on dark nights). Red Mrs Access Glory, Jack Sprat, Yellow Dorothy and Grey Ghost lures. -

CRT Conference 2020 – Bus Trips

CRT Conference 2020 – Bus Trips South-eastern Southland fieldtrip 19th March 2020 Welcome and overview of the day. Invercargill to Gorge Road We are travelling on the Southern Scenic Route from Invercargill to the Catlins. Tisbury Old Dairy Factory – up to 88 around Southland We will be driving roughly along the boundary between the Southland Plains and Waituna Ecological Districts. The Southland Plains ED is characterized by a variety of forest on loam soils, while the Waituna District is characterized by extensive blanket bog with swamps and forest. Seaward Forest is located near the eastern edge of Invercargill to the north of our route today. It is the largest remnant of a large forest stand that extended from current day Invercargill to Gorge Road before European settlement and forest clearance. Long our route to Gorge Road we will see several other smaller forest remnants. The extent of Seaward forest is shown in compiled survey plans of Theophilus Heale from 1868. However even the 1865 extent of the forest is much reduced from the original pre-Maori forest extent. Almost all of Southland was originally forest covered with the exception of peat bogs, other valley floor wetlands, braided river beds and the occasional frost hollows. The land use has changed in this area over the previous 20 years with greater intensification and also with an increase in dairy farming. Surrounding features Takitimus Mtns – Inland (to the left) in the distance (slightly behind us) – This mountain range is one of the most iconic mountains in Southland – they are visible from much of Southland. -

I-SITE Visitor Information Centres

www.isite.nz FIND YOUR NEW THING AT i-SITE Get help from i-SITE local experts. Live chat, free phone or in-person at over 60 locations. Redwoods Treewalk, Rotorua tairawhitigisborne.co.nz NORTHLAND THE COROMANDEL / LAKE TAUPŌ/ 42 Palmerston North i-SITE WEST COAST CENTRAL OTAGO/ BAY OF PLENTY RUAPEHU The Square, PALMERSTON NORTH SOUTHERN LAKES northlandnz.com (06) 350 1922 For the latest westcoastnz.com Cape Reinga/ information, including lakewanaka.co.nz thecoromandel.com lovetaupo.com Tararua i-SITE Te Rerenga Wairua Far North i-SITE (Kaitaia) 43 live chat visit 56 Westport i-SITE queenstownnz.co.nz 1 bayofplentynz.com visitruapehu.com 45 Vogel Street, WOODVILLE Te Ahu, Cnr Matthews Ave & Coal Town Museum, fiordland.org.nz rotoruanz.com (06) 376 0217 123 Palmerston Street South Street, KAITAIA isite.nz centralotagonz.com 31 Taupō i-SITE WESTPORT | (03) 789 6658 Maungataniwha (09) 408 9450 Whitianga i-SITE Foxton i-SITE Kaitaia Forest Bay of Islands 44 Herekino Omahuta 16 Raetea Forest Kerikeri or free phone 30 Tongariro Street, TAUPŌ Forest Forest Puketi Forest Opua Waikino 66 Albert Street, WHITIANGA Cnr Main & Wharf Streets, Forest Forest Warawara Poor Knights Islands (07) 376 0027 Forest Kaikohe Russell Hokianga i-SITE Forest Marine Reserve 0800 474 830 DOC Paparoa National 2 Kaiikanui Twin Coast FOXTON | (06) 366 0999 Forest (07) 866 5555 Cycle Trail Mataraua 57 Forest Waipoua Park Visitor Centre DOC Tititea/Mt Aspiring 29 State Highway 12, OPONONI, Forest Marlborough WHANGAREI 69 Taumarunui i-SITE Forest Pukenui Forest -

Regional Mapping of Groundwater Denitrification Potential and Aquifer Sensitivity

Regional Mapping of Groundwater Denitrification Potential and Aquifer Sensitivity Technical Report Clint Rissmann Groundwater Scientist November 2011 Publication No 2011-12 Contents 1. Executive Summary ...................................................................................... 3 2. Introduction................................................................................................... 6 2.1. Objectives ............................................................................................................................ 6 2.2. Location and Composition of Primary Aquifers ...................................................... 7 2.2.1 General Location ................................................................................................ 7 2.2.2 Composition of Primary Aquifers .................................................................... 8 3. Redox Chemistry of Groundwaters ............................................................. 11 3.1 Background .................................................................................................................. 11 3.2 The Importance of Groundwater Redox State on Nitrate Concentration ......... 12 3.3 Controls over the Redox Status of Groundwater .................................................. 13 4. Aquifer Denitrification Potential or Sensitivity to Nitrate Accumulation .. 15 4.1 Role of Aquifer Materials in Denitrification ........................................................... 15 4.2 Assigning Denitrification Potential to Southland Aquifers -

Waimumu Stream Drainage

tion, Mt', MoNab. WAIMUMU STREAM DRAINAGE. [LOCAL BILL.] ANALYSIS. Title. 14. Alteration of manner of election, Preamble. 15. Meetings of Board. 1. Short Title. 16. Board incorporated. 2. Constitution of district. 17. Board to have within district powers of 8. Board of Trustees. County Council. 4. First election. 18. Control of Waimumu Stream. 5. Ratepayers lists. 19. Board to have powers of Land Drainage 6. Objections. Board. 7. Appeal from list. 20 Additional powers. 8. Qualification of electors. 21. Resolution in exercise of power in Borough 9. Elections. of Mataura. 10. Subsequent elections. 22. Rates. 11. Appointment by Governor. 23. Classification of landis. 12. Election in case of vacancy. 24. Assumption of liabilities by Board. 19, Gaze#ing of eledion. Schedules. A BILL INTITULED AN Aor 00 provide for the Administration of a Tail-race or Flood- Title. channel in the Waimumu Stream constructed by the Mataura Borough Council under a Deed of Arrangement purporting to 6 be made in Pursuance of " The Mining Act, 1898," and for the Formation of a Drainage District in the District drained by the Waimumu Stream. WHEREAS by a deed dated the thirteenth day of May, one thousand preamble. nine ·hundred and two, and purporting to be made between the 10 Minister of Mines of the first part, the Corporation of the Borough of Mataura, acting by the Borough Council, of the second part, certain. landowners therein described of the third part, and certain mining companies therein described of the fourth part, after reciting that by reason of the -

Anglers' Notice for Fish and Game Region Conservation

ANGLERS’ NOTICE FOR FISH AND GAME REGION CONSERVATION ACT 1987 FRESHWATER FISHERIES REGULATIONS 1983 Pursuant to section 26R(3) of the Conservation Act 1987, the Minister of Conservation approves the following Anglers’ Notice, subject to the First and Second Schedules of this Notice, for the following Fish and Game Region: Southland NOTICE This Notice shall come into force on the 1st day of October 2017. 1. APPLICATION OF THIS NOTICE 1.1 This Anglers’ Notice sets out the conditions under which a current licence holder may fish for sports fish in the area to which the notice relates, being conditions relating to— a.) the size and limit bag for any species of sports fish: b.) any open or closed season in any specified waters in the area, and the sports fish in respect of which they are open or closed: c.) any requirements, restrictions, or prohibitions on fishing tackle, methods, or the use of any gear, equipment, or device: d.) the hours of fishing: e.) the handling, treatment, or disposal of any sports fish. 1.2 This Anglers’ Notice applies to sports fish which include species of trout, salmon and also perch and tench (and rudd in Auckland /Waikato Region only). 1.3 Perch and tench (and rudd in Auckland /Waikato Region only) are also classed as coarse fish in this Notice. 1.4 Within coarse fishing waters (as defined in this Notice) special provisions enable the use of coarse fishing methods that would otherwise be prohibited. 1.5 Outside of coarse fishing waters a current licence holder may fish for coarse fish wherever sports fishing is permitted, subject to the general provisions in this Notice that apply for that region. -

Maori Cartography and the European Encounter

14 · Maori Cartography and the European Encounter PHILLIP LIONEL BARTON New Zealand (Aotearoa) was discovered and settled by subsistence strategy. The land east of the Southern Alps migrants from eastern Polynesia about one thousand and south of the Kaikoura Peninsula south to Foveaux years ago. Their descendants are known as Maori.1 As by Strait was much less heavily forested than the western far the largest landmass within Polynesia, the new envi part of the South Island and also of the North Island, ronment must have presented many challenges, requiring making travel easier. Frequent journeys gave the Maori of the Polynesian discoverers to adapt their culture and the South Island an intimate knowledge of its geography, economy to conditions different from those of their small reflected in the quality of geographical information and island tropical homelands.2 maps they provided for Europeans.4 The quick exploration of New Zealand's North and The information on Maori mapping collected and dis- South Islands was essential for survival. The immigrants required food, timber for building waka (canoes) and I thank the following people and organizations for help in preparing whare (houses), and rocks suitable for making tools and this chapter: Atholl Anderson, Canberra; Barry Brailsford, Hamilton; weapons. Argillite, chert, mata or kiripaka (flint), mata or Janet Davidson, Wellington; John Hall-Jones, Invercargill; Robyn Hope, matara or tuhua (obsidian), pounamu (nephrite or green Dunedin; Jan Kelly, Auckland; Josie Laing, Christchurch; Foss Leach, stone-a form of jade), and serpentine were widely used. Wellington; Peter Maling, Christchurch; David McDonald, Dunedin; Bruce McFadgen, Wellington; Malcolm McKinnon, Wellington; Marian Their sources were often in remote or mountainous areas, Minson, Wellington; Hilary and John Mitchell, Nelson; Roger Neich, but by the twelfth century A.D. -

South Island Fishing Regulations for 2020

Fish & Game 1 2 3 4 5 6 Check www.fishandgame.org.nz for details of regional boundaries Code of Conduct ....................................................................4 National Sports Fishing Regulations ...................................... 5 First Schedule ......................................................................... 7 1. Nelson/Marlborough .......................................................... 11 2. West Coast ........................................................................16 3. North Canterbury ............................................................. 23 4. Central South Island ......................................................... 33 5. Otago ................................................................................44 6. Southland .........................................................................54 The regulations printed in this guide booklet are subject to the Minister of Conservation’s approval. A copy of the published Anglers’ Notice in the New Zealand Gazette is available on www.fishandgame.org.nz Cover Photo: Jaymie Challis 3 Regulations CODE OF CONDUCT Please consider the rights of others and observe the anglers’ code of conduct • Always ask permission from the land occupier before crossing private property unless a Fish & Game access sign is present. • Do not park vehicles so that they obstruct gateways or cause a hazard on the road or access way. • Always use gates, stiles or other recognised access points and avoid damage to fences. • Leave everything as you found it. If a gate is open or closed leave it that way. • A farm is the owner’s livelihood and if they say no dogs, then please respect this. • When driving on riverbeds keep to marked tracks or park on the bank and walk to your fishing spot. • Never push in on a pool occupied by another angler. If you are in any doubt have a chat and work out who goes where. • However, if agreed to share the pool then always enter behind any angler already there. • Move upstream or downstream with every few casts (unless you are alone).