Expanding Finance for Water Service Providers in Kenya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sidian Bank Limited Annual Report and Financial

SIDIAN BANK LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2017 Sidian Bank Limited Financial Statements For the year ended 31 December 2017 Contents Page Corporate information 1 - 2 Report of the Directors 3 Business review 4 - 6 Statement on corporate governance 7 - 9 Statement of Directors’ responsibilities 10 Report of the independent auditor 11 - 13 Financial statements: Statement of profit or loss and other comprehensive income 14 Statement of financial position 15 Statement of changes in equity 16 Statement of cash flows 17 Notes to the financial statements 18 - 69 Sidian Bank Limited Corporate Information For the year ended 31 December 2017 Directors Executive Chege Thumbi (Appointed 22 August 2017) Titus Karanja* (Resigned 31 July 2017) Non-executive James Mworia (Chairman) Mary Ann Musangi Kimanthi Mutua Tom Kariuki Independent Catherine Mturi-Wairi Independent Donald B Kipkorir** Independent (Resigned 26 July 2017) Oscar Kang’oro Independent (Appointed 5 January 2018) Board Committees Audit and Risk Committee Catherine Mturi-Wairi - Chairperson Kimanthi Mutua Tom Kariuki Mary Ann Musangi Oscar Kangoro Asset and Liability Committee Kimanthi Mutua - Chairperson Catherine Mturi-Wairi Chege Thumbi Mary Anne Musangi Oscar Kangoro Credit Committee Tom Kariuki - Chairperson Kimanthi Mutua Chege Thumbi Oscar Kangoro Nominations and Governance Committee Mary Ann Musangi - Chairperson Catherine Mturi-Wairi Chege Thumbi Tom Kariuki * Mr. Titus Karanja continued in the Bank as a consultant until 31 December 2017. ** Following the resignation of Mr. Donald B Kipkorir, all Committees were reconstituted as search for a new Director began. *** Details of the Brand Committee and the ICT and Operations Committee are included in the Statement on Corporate Governance. -

List of the Main Kenyan Financial Institutions That Provide Loans Tothe Agriculutre Sector

LIST OF THE MAIN KENYAN FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS THAT PROVIDE LOANS TOTHE AGRICULUTRE SECTOR Type of Org Organisation Service for Brief description Website Reference Contact Id Name SHF Zahid Mustafa - Barclays Commercial 1 Barclays is supporting small holder farmers finance. Consumer Banking Limited Bank Director Commercial Julius Ngesa - Head Commercial They have several product to serve farmers. Value Chains supported: dairy, tea and 2 Bank of Africa http://cbagroup.com/ of Business Bank sugar cane (CBA) Development Business Revolving Credit Plan gives you a line of credit which can be paid off over two to five years. Once you have repaid 25% of the loan, you can withdraw funds up to the original limit, without affecting your monthly repayments. The loan can be linked to your business account, so you can transfer funds electronically An Agricultural Production Loan (APL) is a short-term credit that lets you pay for your agricultural input costs. This product is suitable for grain farmers cultivating on either CFC Stanbic Commercial dry land or on an irrigation basis. Loans are provided to individual farmers, groups and http://www.stanbicban Derrick Kimani - 3 Bank Bank legal entities in the agricultural sector, including commercial farmers and agri- k.co.ke/ Digital Channels businesses. Input costs that qualify for production credit include: Seeds and fertilizer; Fuel, oil and lubricants; Herbicides and pesticides; Repairs and maintenance; Crop insurance premiums The vehicle and asset finance packages are designed to support business‚ cash flow and tax requirements. Vehicles and assets we finance include: Tractors; Harvesters; Centre pivots; Solar panels Dairy Asset Finance, value chain finance. -

Annual Report 2019 East African Development Bank

Your partner in development ANNUAL REPORT 2019 EAST AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK 2 2019 ANNUAL REPORT EAST AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK EAST AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK EAST AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK ANNUAL REPORT 2019 3 2019 ANNUAL REPORT EAST AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK CORPORATE PROFILE OF EADB Uganda (Headquarters) Plot 4 Nile Avenue EADB Building P. O. Box 7128 Kampala, Uganda Kenya Country office, Kenya 7th Floor, The Oval Office, Ring Road, Rwanda REGISTERED Parklands Westland Ground Floor, OFFICE AND P.O. Box 47685, Glory House Kacyiru PRINCIPAL PLACE Nairobi P.O. Box 6225, OF BUSINESS Kigali Rwanda Tanzania 349 Lugalo/ Urambo Street Upanga P.O. Box 9401 Dar es Salaam, Tanzania BANKERS Uganda (Headquarters) Standard Chartered –London Standard Chartered – New York Standard Chartered - Frankfurt Citibank – London Citibank – New York AUDITOR Standard Chartered – Kampala PricewaterhouseCoopers Stanbic – Kampala Certified Public Accountants, Citibank – Kampala 10th Floor Communications House, 1 Colville Street, Kenya P.O. Box 882 Standard Chartered Kampala, Uganda Rwanda Bank of Kigali Tanzania Standard Chartered 4 2019 ANNUAL REPORT EAST AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK EAST AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK ESTABLISHMENT The East African Development Bank (EADB) was established in 1967 SHAREHOLDING The shareholders of the EADB are Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania and Rwanda. Other shareholders include the African Development Bank (AfDB), the Netherlands Development Finance Company (FMO), German Investment and Development Company (DEG), SBIC-Africa Holdings, NCBA Bank Kenya, Nordea Bank of Sweden, Standard Chartered Bank, London, Barclays Bank Plc., London and Consortium of former Yugoslav Institutions. MISSION VISION OUR CORE To promote sustain- To be the partner of VALUES able socio-economic choice in promoting development in East sustainable socio-eco- Africa by providing nomic development. -

Automated Clearing House Participants Bank / Branches Report

Automated Clearing House Participants Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 Bank: 01 Kenya Commercial Bank Limited (Clearing centre: 01) Branch code Branch name 091 Eastleigh 092 KCB CPC 094 Head Office 095 Wote 096 Head Office Finance 100 Moi Avenue Nairobi 101 Kipande House 102 Treasury Sq Mombasa 103 Nakuru 104 Kicc 105 Kisumu 106 Kericho 107 Tom Mboya 108 Thika 109 Eldoret 110 Kakamega 111 Kilindini Mombasa 112 Nyeri 113 Industrial Area Nairobi 114 River Road 115 Muranga 116 Embu 117 Kangema 119 Kiambu 120 Karatina 121 Siaya 122 Nyahururu 123 Meru 124 Mumias 125 Nanyuki 127 Moyale 129 Kikuyu 130 Tala 131 Kajiado 133 KCB Custody services 134 Matuu 135 Kitui 136 Mvita 137 Jogoo Rd Nairobi 139 Card Centre Page 1 of 42 Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 140 Marsabit 141 Sarit Centre 142 Loitokitok 143 Nandi Hills 144 Lodwar 145 Un Gigiri 146 Hola 147 Ruiru 148 Mwingi 149 Kitale 150 Mandera 151 Kapenguria 152 Kabarnet 153 Wajir 154 Maralal 155 Limuru 157 Ukunda 158 Iten 159 Gilgil 161 Ongata Rongai 162 Kitengela 163 Eldama Ravine 164 Kibwezi 166 Kapsabet 167 University Way 168 KCB Eldoret West 169 Garissa 173 Lamu 174 Kilifi 175 Milimani 176 Nyamira 177 Mukuruweini 180 Village Market 181 Bomet 183 Mbale 184 Narok 185 Othaya 186 Voi 188 Webuye 189 Sotik 190 Naivasha 191 Kisii 192 Migori 193 Githunguri Page 2 of 42 Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 194 Machakos 195 Kerugoya 196 Chuka 197 Bungoma 198 Wundanyi 199 Malindi 201 Capital Hill 202 Karen 203 Lokichogio 204 Gateway Msa Road 205 Buruburu 206 Chogoria 207 Kangare 208 Kianyaga 209 Nkubu 210 -

The Largest Trade and Export Finance Event for Sub-Saharan Africa

The largest trade and export finance event for Sub-Saharan Africa... delivered digitally www.gtreview.com/gtrafrica Post-event media kit #GTRAfrica INTRODUCTION & CONTACTS “The GTR team has really gone to great lengths to make very lovely lemonade with the lemons that COVID-19 has given to all of us this The largest trade and export year. I look forward to attending again in the future.” finance event for Sub-Saharan JM Ndawula, Africa Finance Corporation Africa – delivered digitally Drawing on the high-level expertise, comprehensive market coverage and unrivalled industry connections of GTR’s Africa-focused gatherings in Cape Town, Victoria Falls and London, GTR Africa 2020 Virtual which took place on October 20-23, combining a mixture of live-streamed and pre-recorded content and targeted networking through GTR’s dynamic virtual event platform. Spread over 4 days and combining 3 distinct events into the one extended virtual offering to capture a wider audience, this new format provided the opportunity for more detailed focus on key markets, innovation, trade and commodity flows, infrastructure and the wider implications of global disruption. The event also featured our inaugural Digital Deal Room, a bespoke origination and investment matching platform populated with unique opportunities for investors, held in collaboration with Orbitt. Sponsorship opportunities Speaking opportunities Marketing & media opportunities Peter Gubbins Jeff Ando Elisabeth Spry Join the conversation at #GTRAfrica CEO Director, Content Marketing Manager [email protected] -

Sidian Bank – Tarrif Guide

SIDIAN BANK 2021 TARIFF GUIDE TRADE FINANCE A ACCOUNT OPENING BALANCES L STATEMENT Opening Balance Standard Annual Statement - Savings Account Free 1 IMPORT LETTER OF CREDIT Standard Monthly Statement - Current Account Free Opening Commission 0.5% per quarter or part thereof min Ksh. 2,000.00 Savings Accounts: Standard Annual Statement - Group Account Free General Amendments Ksh. 3,500.00 Premium Savings Account Ksh. 10,000.00 Interim Statement Ksh. 150.00 per page Amendment Fee(Extensions/Increase in amount) 0.5% per quarter or part thereof min Ksh. 2,000.00 Msingi Savings Account Ksh. 5,000.00 or FCY equivalent Request for Statement - Max 1 year Ksh. 200.00 per page Settlement/Retirement Commission 0.25% one off min Ksh. 2,000.00 USD.100 or equivalent Certificate of Balance Ksh. 500.00 Discrepancy fees Current Accounts: LC Cancellation charges Ksh. 5,000.00 E-Statement Free Business Account Ksh. 2,000.00 Expired unutilized fee Ksh. 5,000.00 Signature Account KES. 15,000.00 or FCY equivalent Revenue Stamp N/A Flexxy Account KES. 10,000.00 or FCY equivalent M OTHER SERVICES Document Examination Ksh. 4,000.00 per set of documents Ungana Account KES. 2,000.00 Release of Documents against Customer Indemnity Ksh. 3,000.00 Audit Confirmation Ksh. 1,000.00 Swift Charges Ksh. 2,500.00 per swift Transactional Accounts: Certification Ksh. 100.00 per document Nawiri Nil Bank Document Copies (Cheques/Letter/Deposit slips & other Bank copies) Ksh. 100.00 per copy 2 EXPORT LETTER OF CREDIT Mshahara Nil Overnight holding charges for cheques without funds Ksh. -

Most Socially Active Professionals

Africa’s Most Socially Active Financial Services Professionals – October 2020 Position Company Name LinkedIN URL Location Size No. Employees on LinkedIn No. Employees Shared (Last 30 Days) % Shared (Last 30 Days) 1 Monocle Solutions https://www.linkedin.com/company/583208 South Africa 201-500 204 60 29.41% 2 Standard Bank Moçambique https://www.linkedin.com/company/18022936 Mozambique 1001-5000 499 94 18.84% 3 Global Accelerex Ltd. https://www.linkedin.com/company/2866832 Nigeria 201-500 201 35 17.41% 4 eTranzact International PLC https://www.linkedin.com/company/10539350 Nigeria 201-500 258 39 15.12% 5 Groupe COFINA https://www.linkedin.com/company/9407515 Côte d'Ivoire 1001-5000 494 74 14.98% 6 Premium Card https://www.linkedin.com/company/18312464 Egypt 1001-5000 211 30 14.22% 7 CREDIT DIRECT LIMITED https://www.linkedin.com/company/11500510 Nigeria 501-1000 479 68 14.20% 8 Cellulant https://www.linkedin.com/company/136596 Kenya 201-500 436 59 13.53% 9 Coronation Merchant Bank https://www.linkedin.com/company/11047716 Nigeria 201-500 201 26 12.94% 10 Tanmeyah Micro Enterprise Serviceshttps://www.linkedin.com/company/1043448 Egypt 1001-5000 269 34 12.64% 11 Momentum Metropolitan Holdingshttps://www.linkedin.com/company/20135773 Limited South Africa 10001+ 958 121 12.63% 12 Standard Lesotho Bank https://www.linkedin.com/company/6083999 Lesotho 1001-5000 428 53 12.38% 13 First National Bank GH https://www.linkedin.com/company/18530500 Ghana 201-500 235 29 12.34% 14 Hereford Group https://www.linkedin.com/company/2161990 South Africa 201-500 327 40 12.23% 15 ALIOS FINANCE https://www.linkedin.com/company/519387 Tunisia 201-500 234 28 11.97% 16 KPMG East Africa https://www.linkedin.com/company/338470 Kenya 1001-5000 640 76 11.88% 17 Zedvance Finance Limited https://www.linkedin.com/company/5275905 Nigeria 201-500 330 39 11.82% 18 Asset & Resource Management Holdinghttps://www.linkedin.com/company/1014132 Company (ARM HoldCo). -

Social Capital and Internationalization of Commercial Banks in Kenya

ISSN 2519-8564 (рrint), ISSN 2523-451X (online). European Journal of Management Issues. – 2020. – 28 (1-2) European Journal of Management Issues Volume 28(1-2), 2020, pp.41-51 DOI: 10.15421/192005 Received: 12 February2020; 08 April 2020 Revised: 27 March 2020; 13 May 2020 Accepted: 03 June 2020 Published: 25 June 2020 UDC classification: 336 JEL Classification: M19 Social capital and internationalization of commercial banks in Kenya P. P. Omondi‡, J. W. Ndegwa‡‡, ‡‡‡ T. C. Okech Purpose – tо study sought to delve into social capital and commercial banks' internationalization in Kenya Drawing on the internationalization concept. Design/Method/Approach. The research adopted a positivist philosophical approach and used a descriptive cross-sectional research design targeting top and middle-level managers in Kenya's commercial banks. Data was collected using a structured questionnaire and analyzed using SPSS version 22.0 for both descriptive and inferential statistics. Structural Equation Modelling was used to establish the influence of social capital on commercial banks' internationalization in Kenya. Findings. The findings established a significant and positive relationship between the components of social capital: inter-cultural empathy, inter- personal impact and diplomacy, and commercial banks' internationalization. Practical implications. The results have significant consequences: Firstly, social capital has a positive and statistically significant ‡Philip Peters Omondi, relationship with commercial banks' internationalization. Head of Trade Finance, NCBA Bank, Secondly, all dimensions of social capital affect the acquisition of Nairobi, Kenya, foreign market knowledge and financial resources. Thirdly, the use e-mail: [email protected], https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5213-7269 of individuals' social capital often changes during internationalization. -

Sanitation Financing: Lessons Learnt from Application of Different Financing Instruments in Busia County, Kenya

JOSPHAT et al. 41st WEDC International Conference, Egerton University, Nakuru, Kenya, 2018 TRANSFORMATION TOWARDS SUSTAINABLE AND RESILIENT WASH SERVICES Sanitation financing: lessons learnt from application of different financing instruments in Busia county, Kenya M. Josphat (Kenya), G. Kimathi, R. Moraro & J. Temu PAPER 3066 Financial Inclusion Improves Sanitation and Health in Kenya is a Dutch-Government funded project implemented in Busia and Kilifi Counties. The project is founded on a Public-Private Partnership arrangement to create an enabling environment for market-driven approach for scaling up sanitation. The intervention combines demand generation and private sector involvement in developing and delivering sanitation products and services to underserved rural communities. The mainstay strategy applied was Community Led Total sanitation plus (CLTS+) approach. The plus entails financial inclusion targeting communities without sanitation facilities through financial literacy and micro-lending for sanitation improvement. As part of supply side development, Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in sanitation business having also been financially included to strengthen their capacity to respond to thus generated demand. A combination of expanded markets coupled with demand generation has contributed to access to improved sanitation, promising health and livelihood improvements. Introduction A huge proportion (70.3%) of Kenya’s rural population lack access to improved sanitation with only 15% having attained open defecation free status (WHO/UNICEF, 2015). Inadequate access to sanitation affects the economies negatively with up to 7% Gross Domestic Product reduction besides the well-known negative health and social outcomes (Hutton & Chase, 2016.) Every year, each Kenyan spends an estimated US$12 of their earnings an estimated US$0.56Billion in sanitation-related ailments (Oxford Economics, 2016). -

The Relationship Between Bank Performance and Market Returns in Listed Banks in Kenya

Strathmore University SU+ @ Strathmore University Library Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2018 The Relationship between bank performance and market returns in listed banks in Kenya John Ndegwa Strathmore Business School (SBS) Strathmore University Follow this and additional works at https://su-plus.strathmore.edu/handle/11071/6067 Recommended Citation Ndegwa, J. (2018). The Relationship between bank performance and market returns in listed banks in Kenya (Thesis). Strathmore University. Retrieved from http://su- plus.strathmore.edu/handle/11071/6067 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by DSpace @Strathmore University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DSpace @Strathmore University. For more information, please contact [email protected] The Relationship between bank performance and market returns in listed banks in Kenya By: John Ndegwa Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Business Administration at Strathmore University. Strathmore University Business School Strathmore University Nairobi, Kenya May, 2018 DECLARATION I declare that this work has not been previously submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the dissertation contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the thesis itself. John Ndegwa Admission Number: MBA/15411 31/05/18 (Signature) ………………………………… (Date) …………………………………… Approval This research proposal has been submitted with my approval as the supervisor. Signature ………………………………….. Date …………………………… Dr. Thomas Kibua Strathmore University i ABSTRACT The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between bank financial performance and stock price returns. -

Factors Affecting Strategy Implementation in Kenyan Banks: a Case Study of Consolidated Bank Kenya Limited

FACTORS AFFECTING STRATEGY IMPLEMENTATION IN KENYAN BANKS: A CASE STUDY OF CONSOLIDATED BANK KENYA LIMITED BY MARGARET NJOKI KIMANI A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, SCHOOL OF BUSINESS, UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI 2017 DECLARATION This is to declare that this research project is my original work and has not been presented to any other university or institution of higher learning for examination or for any other purpose. Signed …………………………………….. Date ………………………. MARGARET NJOKI KIMANI D61/73143/2012 APPROVAL This is to confirm that this research project has been submitted for examination with my approval as the official university supervisor. Signed …………………………………….. Date ………………………. PROF. BITANGE NDEMO School of Business, University of Nairobi ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I am grateful to God, whose empowerment and guidance has been tremendous. This course would not have been successful had it not been for the valuable support, assistance and guidance from my family members, friends and colleagues. My classmates for the great discussions and insights during my MBA programme. I am grateful to all of them for their support. I am obliged to mention a few to acknowledge their special contribution. I acknowledge my supervisor Professor Bitange Ndemo for his constant encouragement; guidance and wise counsel which enabled me complete this work in good time. I wish to salute my family members for their unrelenting support and encouragement. Further appreciation is extended to the Heads of Departments and the CEO of Consolidated Bank Kenya Limited for their fullest cooperation throughout the project. Finally I wish to sincerely thank all my friends as well as relatives who in one way or the other supported me in the process of conducting this study. -

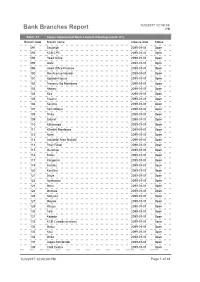

Bank Branches Report PM

1/23/2017 12:40:40 Bank Branches Report PM Bank: 01 Kenya Commercial Bank Limited (Clearing centre: 01) Branch code Branch name Closure date Status 091 Eastleigh 2099-01-01 Open 092 KCB CPC 2099-01-01 Open 094 Head Office 2099-01-01 Open 095 Wote 2099-01-01 Open 096 Head Office Finance 2099-01-01 Open 100 Moi Avenue Nairobi 2099-01-01 Open 101 Kipande House 2099-01-01 Open 102 Treasury Sq Mombasa 2099-01-01 Open 103 Nakuru 2099-01-01 Open 104 Kicc 2099-01-01 Open 105 Kisumu 2099-01-01 Open 106 Kericho 2099-01-01 Open 107 Tom Mboya 2099-01-01 Open 108 Thika 2099-01-01 Open 109 Eldoret 2099-01-01 Open 110 Kakamega 2099-01-01 Open 111 Kilindini Mombasa 2099-01-01 Open 112 Nyeri 2099-01-01 Open 113 Industrial Area Nairobi 2099-01-01 Open 114 River Road 2099-01-01 Open 115 Muranga 2099-01-01 Open 116 Embu 2099-01-01 Open 117 Kangema 2099-01-01 Open 119 Kiambu 2099-01-01 Open 120 Karatina 2099-01-01 Open 121 Siaya 2099-01-01 Open 122 Nyahururu 2099-01-01 Open 123 Meru 2099-01-01 Open 124 Mumias 2099-01-01 Open 125 Nanyuki 2099-01-01 Open 127 Moyale 2099-01-01 Open 129 Kikuyu 2099-01-01 Open 130 Tala 2099-01-01 Open 131 Kajiado 2099-01-01 Open 133 KCB Custody services 2099-01-01 Open 134 Matuu 2099-01-01 Open 135 Kitui 2099-01-01 Open 136 Mvita 2099-01-01 Open 137 Jogoo Rd Nairobi 2099-01-01 Open 139 Card Centre 2099-01-01 Open 1/23/2017 12:40:40 PM Page 1 of 44 1/23/2017 12:40:40 Bank Branches Report PM 140 Marsabit 2099-01-01 Open 141 Sarit Centre 2099-01-01 Open 142 Loitokitok 2099-01-01 Open 143 Nandi Hills 2099-01-01 Open 144 Lodwar 2099-01-01