Sean Loughran HIS 492 03: Seminar in History Professor Meg D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Environmental Health Criteria 110 Tricresyl Phosphate

Environmental Health Criteria 110 Tricresyl phosphate Please note that the layout and pagination of this web version are not identical with the printed version. Tricresyl phosphate (EHC 110, 1990) INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMME ON CHEMICAL SAFETY ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH CRITERIA 110 TRICRESYL PHOSPHATE This report contains the collective views of an international group of experts and does not necessarily represent the decisions or the stated policy of the United Nations Environment Programme, the International Labour Organisation, or the World Health Organization. Published under the joint sponsorship of the United Nations Environment Programme, the International Labour Organisation, and the World Health Organization World Health Orgnization Geneva, 1990 The International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS) is a joint venture of the United Nations Environment Programme, the International Labour Organisation, and the World Health Organization. The main objective of the IPCS is to carry out and disseminate evaluations of the effects of chemicals on human health and the quality of the environment. Supporting activities include the development of epidemiological, experimental laboratory, and risk-assessment methods that could produce internationally comparable results, and the development of manpower in the field of toxicology. Other activities carried out by the IPCS include the development of know-how for coping with chemical accidents, coordination of laboratory testing and epidemiological studies, and promotion of research on the mechanisms of the biological action of chemicals. WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Tricresyl phosphate. (Environmental health criteria ; 110) 1.Tritolyl phosphates - adverse effects 2.Tritolyl phosphates - toxicity I.Series Page 1 of 84 Tricresyl phosphate (EHC 110, 1990) ISBN 92 4 157110 1 (NLM Classification: QV 627) ISSN 0250-863X The World Health Organization welcomes requests for permission to reproduce or translate its publications, in part or in full. -

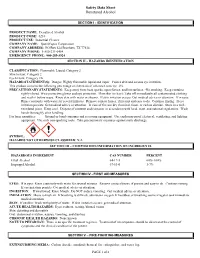

Parks Denatured Alcohol

Material Safety Data Sheet Section 1 General Information Manufacturer: Zinsser Company, Inc. 173 Belmont Drive Somerset, NJ 08875 (732) 469-8100 Emergency Telephone: Chemtrec (800) 424-9300 Date: December 1, 2006 Product Name: Parks Denatured Alcohol Codes: 002121 002122 002123 002125 Section 2 Hazardous Ingredients OSHA ACGIH Hazardous Component CAS# PEL TLV Ethanol 64-17-5 1000 ppm 1000 ppm Methanol 67-56-1 200 ppm 200 ppm 250 ppm STEL Methyl Isobutyl Ketone 108-10-1 100 ppm 50 ppm 75 ppm STEL Ethyl Acetate 141-78-6 400 ppm 400 ppm Rubber Solvent 64742-89-8 500 ppm 400 ppm Section 3 Hazard Identification Emergency Overview: This product is a clear liquid with a characteristic smell and flash point of 41oF. Primary Routes of Exposure: Skin Contact Eye Contact Inhalation Potential Acute Health Effects: Eye: Contact may cause eye irritation. N/A: Not Applicable N/D: Not Determined N/E: Not Established N/R: Not Required Est.: Estimated Parks Denatured Alcohol (12-01-06) Page 1 of 6 pages. Skin: May cause skin irritation. Repeated or prolonged contact with skin may cause dermatitis. Ingestion: May be fatal or cause blindness if swallowed. Inhalation: May cause respiratory tract irritation. Potential Chronic Health Effects: Signs and Symptoms: Prolonged exposure to excessive concentrations of ethanol may result in irritation of mucous membranes, headache, drowsiness, fatigue and narcosis. Methanol is also narcotic in effect and its effects are cumulative. Overexposure to methanol can result in acidosis and visual disturbances which may progress to permanent loss of vision. (See also Sections 4, 8, and 11for related information) Section 4 First Aid Measures Eye contact: Immediately flush eyes with water for at least 15 minutes. -

Non-Beverage Alcohol Consumption & Harm Reduction Trends

Non-beverage Alcohol Consumption & Harm Reduction Trends A Report for the Thunder Bay Drug Strategy Prepared by Kim Ongaro HBSW Placement Lakehead University June 15, 2017 Non-beverage Alcohol Consumption & Harm Reduction Trends What is non-beverage alcohol? Non-beverage alcohol can go by many names in the literature. Broadly, it is understood to be liquids containing a form of alcohol that is not intended for human consumption (e.g., mouthwash, hand sanitizer, etc.) that are consumed instead of beverage alcohol for the purposes of intoxication or a “high” (Crabtree, Latham, Bird, & Buxton, 2016; Egbert, Reed, Powell, Liskow, & Liese, 1985). Within the literature, there are different definitions for non- beverage alcohols, including surrogate alcohol, illicit alcohol and unrecorded alcohol. Unrecorded alcohol, as defined by the World Health Organization, is untaxed alcohol outside of government regulation including legal or illegal homemade alcohol, alcohol that is smuggled from an outside country (and therefore is not tracked by its sale within the country of consumption), and alcohol of the “surrogate” nature (World Health Organization Indicator and Measurement Registry, 2011). Surrogate alcohol is alcohol that is not meant for human consumption, and is generally apparent as high concentrations of ethanol in mouthwash, hand sanitizers, and other household products (Lachenmeier, Rehm, & Gmel, 2007; World Health Organization Indicator and Measurement Registry, 2011). Surrogate alcohols also include substances containing methanol, isopropyl alcohol, and ethylene glycol (Lachenmeier et al., 2007). Nonbeverage alcohol and surrogate alcohol can be used interchangeably, but Lachenmeier et al., (2007), goes even further to include alcohol that is homemade in their definition of surrogate alcohol, as they stated that this alcohol is sometimes created using some form of non-beverage alcohol. -

Safety Data Sheet Denatured Alcohol

Safety Data Sheet Denatured Alcohol SECTION I - IDENTIFICATION PRODUCT NAME: Denatured Alcohol PRODUCT CODE: 6210 PRODUCT USE: Industrial Cleaner COMPANY NAME: QuestVapco Corporation COMPANY ADDRESS: PO Box 624 Brenham, TX 77834 COMPANY PHONE: 1-800-231-0454 EMERGENCY PHONE: 800-255-3924 SECTION II – HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION CLASSIFICATION: Flammable Liquid: Category 2 Skin Irritant: Category 2 Eye Irritant: Category 2A HAZARD STATEMENT(S): Danger: Highly flammable liquid and vapor Causes skin and serious eye irritation. This product contains the following percentage of chemicals of unknown toxicity: 0% PRECAUTIONARY STATEMENTS: Keep away from heat, sparks, open flames, and hot surfaces. -No smoking. Keep container tightly closed. Wear protective gloves and eye protection. If on skin (or hair): Take off immediately all contaminated clothing and wash it before reuse. Rinse skin with water or shower. If skin irritation occurs: Get medical advice or attention. If in eyes: Rinse cautiously with water for several minutes. Remove contact lenses, if present and easy to do. Continue rinsing. If eye irritation persists: Get medical advice or attention. In case of fire use dry chemical, foam, or carbon dioxide. Store in a well- ventilated place. Keep cool. Dispose of contents and container in accordance with local, state, and national regulations. Wash hands thoroughly after handling. For large quantities: Ground or bond container and receiving equipment. Use explosion-proof electrical, ventilating, and lighting equipment. Use only non-sparking tools. Take precautionary measures against static discharge. SYMBOL: HAZARDS NOT OTHERWISE CLASSIFIED: N/A SECTION III – COMPOSITION/INFORMATION ON INGREDIENTS HAZARDOUS INGREDIENT CAS NUMBER PERCENT Ethyl Alcohol 64-17-5 60%-100% Isopropyl Alcohol 67-63-0 3-7% SECTION IV - FIRST AID MEASURES EYES: If in eyes: Rinse cautiously with water for several minutes. -

Southern Music and the Seamier Side of the Rural South Cecil Kirk Hutson Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1995 The ad rker side of Dixie: southern music and the seamier side of the rural South Cecil Kirk Hutson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Folklore Commons, Music Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hutson, Cecil Kirk, "The ad rker side of Dixie: southern music and the seamier side of the rural South " (1995). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 10912. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/10912 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthiough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproductioiL In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Surrogate Alcohol: What Do We Know and Where Do We Go?

Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research Vol. 31, No. 10 October 2007 Surrogate Alcohol: What Do We Know and Where Do We Go? Dirk W. Lachenmeier, Ju¨rgen Rehm, and Gerhard Gmel Background: Consumption of surrogate alcohols (i.e., nonbeverage alcohols and illegally pro- duced alcohols) was shown to impact on different causes of death, not only poisoning or liver dis- ease, and appears to be a major public health problem in Russia and elsewhere. Methods: A computer-assisted literature review on chemical composition and health conse- quences of ‘‘surrogate alcohol’’ was conducted and more than 70 references were identified. A wider definition of the term ‘‘surrogate alcohol’’ was derived, including both nonbeverage alcohols and illegally produced alcohols that contain nonbeverage alcohols. Results: Surrogate alcohol may contain substances that cause severe health consequences including death. Known toxic constituents include lead, which may lead to chronic toxicity, and methanol, which leads to acute poisoning. On the other hand, the role of higher alcohols (e.g., propanol, isobutanol, and isoamyl alcohol) in the etiology of surrogate-associated diseases is cur- rently unclear. Whether other constituents of surrogates have contributed to the high all-cause mortality over and above the effect of ethanol in recent studies also remains unclear. Conclusions: Given the high public health importance associated with the consumption of sur- rogate alcohols, further knowledge on its chemical composition is required as well as research on its links to various disease endpoints should be undertaken with priority. Some interventions to reduce the harm resulting from surrogate alcohol could be undertaken already at this point. -

Issue No. 14 from Agent's Business, Production, Processing and Marketing Information Center

A private sector Agro-Ent*rprises advice and assistance service to stimulate the successful development of agro-products, ente.pises and export markets in Sri Lanka. Issue No. 14 from AgEnt's business, production, processing and marketing information center. tOMATIC CROPS DOMESTIC/EXPORT PRODUCTION AND MARKETING WORKSHOP 7TH MARCH 1994, LANKA OBEROI HOTEL Typical illustrations of Aromatic crops production/marketing publications held in AgEnm's Business Information Center which could be of interest to aromatic growers/processors/ export marketers. Prepared by : Dr. Tom Davies - Aromatic Crops Agronomist Anthony Dalgleish - AgEnt International Marketing/ Agro-Processing Advisor. Fihih Floo l)eiitsche Bank ltiilling 86, GfllIRod, (olonilo 3 Sri I uika. Tel: 94-1-1,16447, 446,120 Fax: 9,t-1-4464i,28 A private sector Agro-Entcrprises advice and assistance service to stimulate the successful development of agro-products, enterprises and export markets in Sri Lanka. AROMATIC CROPS DOMESTIC/EXPORT PRODUCTION AND MARKETING WORKSHOP AGENDA 12:00 noon : Arrival of Guests and Registration Snack Lunch 12:30 - 12:40pm : Background to AgEnt Project, advice and assistance it can offer - Mr Richard Hurelbrink Chief of Party/AgEnt 12:40 - 1:40pm : Aromatic Crops: Some potential opportunities for Sri Lanka - Dr Tom Davies Aromatic Crops Specialist/UK 1:40 - 2:30pm : Improved Technology for the Processing of Aromatic Crops in Sri Lanka - Dr R 0 B Wijesekera Senior Partner, Intecnos Associates 2:30 - 2:45pm : Consideration in the Design and Fabrication of Equipment for the Aromatic Plant Industry - Mr C N Ratnatunga Senior Partner Intecnos Associates 2:45 - 3:00pm : Tea 3:00 - 3:30pm : Strategies for the decade of exports spices, essential oils and medicinal herbs - Mr P N S Wijeratna Asst Director Sri Lanka Export Development Board 3:30 - 4:00pm : Open discussion 4:00 - 4:10pm : Conclusion Villh Fho..: ,. -

Based Hand Sanitizer Products During the Public Health Emergency (COVID-19)

Contains Nonbinding Recommendations Temporary Policy for Manufacture of Alcohol for Incorporation Into Alcohol- Based Hand Sanitizer Products During the Public Health Emergency (COVID-19) Guidance for Industry March 2020 Updated February 10, 2021 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) Pharmaceutical Quality/Manufacturing Standards (CGMP)/Over-the-Counter (OTC) Preface Public Comment This guidance is being issued to address the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) public health emergency. This is being implemented without prior public comment because FDA has determined that prior public participation for this guidance is not feasible or appropriate (see section 701(h)(1)(C)(i) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) and 21 CFR 10.115(g)(2)). This guidance document is being implemented immediately, but it remains subject to comment in accordance with the Agency’s good guidance practices. Comments may be submitted at any time for Agency consideration. Submit written comments to the Dockets Management Staff (HFA-305), Food and Drug Administration, 5630 Fishers Lane, Rm. 1061, Rockville, MD 20852. Submit electronic comments to https://www.regulations.gov. All comments should be identified with the docket number FDA-2020-D-1106 and complete title of the guidance in the request. Additional Copies Additional copies are available from the FDA web page titled “ COVID-19-Related Guidance Documents for Industry, FDA Staff, and Other Stakeholders,” available at https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/mcm-issues/coronavirus-disease- 2019-covid-19, and from the FDA web page “Hand Sanitizers | COVID-19” available at: http://wcms-internet.fda.gov/drugs/coronavirus-covid-19-drugs/hand-sanitizers-covid-19. -

9780300205176.Pdf

banned This page intentionally left blank banned A History of Pesticides and the Science of Toxicology Frederick Rowe Davis New Haven & London Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Philip Hamilton McMillan of the Class of 1894, Yale College. Copyright © 2014 by Frederick Rowe Davis. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] (U.S. offi ce) or [email protected] (U.K. offi ce). Set in Galliard with Poetica Display type by Westchester Book Group. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN: 978-0-300-20517-6 (cloth) Library of Congress Control Number: 2014944393 A cata logue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48- 1992 (Permanence of Paper). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To my parents Dan Clifford Davis and Judith Rowe Davis . When the public protests, confronted with some obvious evidence of damaging results of pesticide applications, it is fed little tranquilizing pills of half truth. We urgently need an end to these false assurances, to the sugar coating of unpalatable facts. It is the public that is being asked to assume the risks that the insect controllers calculate. -

Language-Of-The-Blues.Pdf

` ` Ebook published February 1, 2012 by Guitar International Group, LLC Editors: Rick Landers and Matt Warnock Cover Design: Debra Devi Originally published January 1, 2006 by Billboard Books Executive Editor: Bob Nirkind Editor: Meryl Greenblatt Design: Cooley Design Lab Production Manager: Harold Campbell Copyright (c) 2006 by Debra Devi Cover photograph of B.B. King by Dick Waterman courtesy Dick Waterman Music Photography Author photograph by Matt Warnock Additional photographs by: Steve LaVere, courtesy Delta Haze Corporation Joseph A. Rosen, courtesy Joseph A. Rosen Photography Sandy Schoenfeld, courtesy Howling Wolf Photos Mike Shea, courtesy Tritone Photography Toni Ann Mamary, courtesy Hubert Sumlin Blues Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material: 6DPXHO&KDUWHUV³7KH6RQJRI$OKDML)DEDOD.DQXWHK´H[FHUSWIURPThe Roots of the Blues by Samuel Charters, originally published: Boston: M. Boyars, 1981. Transaction Publishers: Excerpt from Deep Down in the Jungle: Negro Narrative Folklore from the Streets of Philadelphia by Roger Abrahams. Warner-7DPHUODQH3XEOLVKLQJ&RUSRUDWLRQ6NXOO0XVLF/\ULFIURP³,:DON2Q*XLOGed 6SOLQWHUV´E\0DF5HEHQQDFN Library of Congress Control Number: 2005924574 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means- graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage-and-retrieval systems- without the prior permission of the author. ` Guitar International Reston, Virginia ` Winner of the 2007 ASC AP Deems Taylor Award for Outstanding Book on Popular Music ³:KDWDJUHDWUHVRXUFH«DVfascinating as it is informative. Debra's passion for the blues VKLQHVWKURXJK´ ±Bonnie Raitt ³(YHU\EOXHVJXLWDULVWQHHGVWRNQRZWKHLUEOXHVKLVWRU\DQGZKHUHWKHEOXHVDUHFRPLQJ IURP'HEUD¶VERRNZLOOWHDFK\RXZKDW\RXUHDOO\QHHGWRNQRZ´± Joe Bonamassa ³7KLVLVDEHDXWLIXOERRN$IWHUKHDULQJµ+HOOKRXQGRQ0\7UDLO¶LQKLJKVFKRRO,ERXJKW every vintage blues record available at the time. -

503 Part 20—Distribution and Use of Denatured Alcohol

Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, Treasury Pt. 20 Section Current OMB Section Current OMB where control where control contained No. contained No. 19.611 ............................................................ 1513–0045 19.719 ............................................................ 1513–0052 1513–0088 19.720 ............................................................ 1513–0052 19.612 ............................................................ 1513–0045 19.724 ............................................................ 1513–0052 1513–0088 19.727 ............................................................ 1513–0052 19.613 ............................................................ 1513–0045 19.729 ............................................................ 1513–0052 19.614 ............................................................ 1513–0045 19.733 ............................................................ 1513–0052 19.615 ............................................................ 1513–0045 19.616 ............................................................ 1513–0056 19.734 ............................................................ 1513–0052 19.617 ............................................................ 1513–0056 19.735 ............................................................ 1513–0038 19.618 ............................................................ 1513–0056 1513–0052 19.619 ............................................................ 1513–0056 19.736 ........................................................... -

GINGER PARALYSIS (Second Report) by MAURICZ I

PUBLIC HEALTH REPORTS VOL 45 OCTOBER 17, 1930 NO. 42 THE PHARMACOLOGICAL ACTION OF CERTAIN PHENOL ESTERS, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE ETIOLOGY OF SO-CALLED GINGER PARALYSIS (Second Report) By MAURICZ I. SMITH, Senior Pharmacologist, National Institute of Health, United States Public Health Service, with the cooperation of E. ELVOVE, Chemist, National Institute of Health, and W. H. FRAZIER, Chemist, Bureau of Industrial Akohol In a preliminary communication (1) on the probable cause of the recent widespread epidemic of the condition clinically described as peripheral multiple neuritis, believed to have resulted from drinking adulterated fluid extract of Jamaica ginger, certain pharmacological and chemical evidence was presented to show that a phenol, firmly bound chemically with phosphoric acid, appeared to be the specific etiologic factor. The precise chemical nature of the phenolic com- pound was not revealed owing to the technical difficulties involved in its isolation and identification, though on the basis of the evidence presented it was suspected to be a phosphoric acid ester of one or more of the cresols. Conldusive evidence on the pharmacological side of this problem was equally lacking, on account of the difficulties experienced in faithfully reproducing the human disease in the usual laboratory animals. After much indirect evidence had been obtained pointing to the cresol ester as the probable immediate cause of the paralysis in question, a successful experiment was conducted upon calves. This experiment showed that the human disease could be faithfully reproduced in the calf, as distinguished from the usual laboratory animals, and that the offending agent must have been contained in a technical grade of tricresyl phosphate, the peculiar action of which was either due to an impurity, to the substance itself, or to a combination thereof with some ginger constituent.