The Practiceof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eif.Co.Uk +44 (0) 131 473 2000 #Edintfest THANK YOU to OUR SUPPORTERS THANK YOU to OUR FUNDERS and PARTNERS

eif.co.uk +44 (0) 131 473 2000 #edintfest THANK YOU TO OUR SUPPORTERS THANK YOU TO OUR FUNDERS AND PARTNERS Principal Supporters Public Funders Dunard Fund American Friends of the Edinburgh Edinburgh International Festival is supported through Léan Scully EIF Fund International Festival the PLACE programme, a partnership between James and Morag Anderson Edinburgh International Festival the Scottish Government – through Creative Scotland – the City of Edinburgh Council and the Edinburgh Festivals Sir Ewan and Lady Brown Endowment Fund Opening Event Partner Learning & Engagement Partner Festival Partners Benefactors Trusts and Corporate Donations Geoff and Mary Ball Richard and Catherine Burns Cruden Foundation Limited Lori A. Martin and Badenoch & Co. Joscelyn Fox Christopher L. Eisgruber The Calateria Trust Gavin and Kate Gemmell Flure Grossart The Castansa Trust Donald and Louise MacDonald Professor Ludmilla Jordanova Cullen Property Anne McFarlane Niall and Carol Lothian The Peter Diamand Trust Strategic Partners The Negaunee Foundation Bridget and John Macaskill The Evelyn Drysdale Charitable Trust The Pirie Rankin Charitable Trust Vivienne and Robin Menzies Edwin Fox Foundation Michael Shipley and Philip Rudge David Millar Gordon Fraser Charitable Trust Keith and Andrea Skeoch Keith and Lee Miller Miss K M Harbinson's Charitable Trust The Stevenston Charitable Trust Jerry Ozaniec The Inches Carr Trust Claire and Mark Urquhart Sarah and Spiro Phanos Jean and Roger Miller's Charitable Trust Brenda Rennie Penpont Charitable Trust Festival -

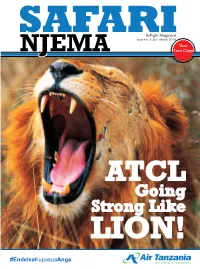

Going Strong Like LION!

In-Flight Magazine SAFARIIssue No.3 Jan - March 2018 Your NJEMA Free Copy ATCL Going Strong Like LION! #EndeleaKupasuaAnga #EndeleaKupasuaAnga Happy New Year 2018 Welcome Aboard ear Passengers and which had facilitated a lot of LET me take this auspicious businesses and helped in promoting opportunity to inspire attention tourism sector, similarly, contributing of your great support that you had in boosting Tanzania’s economy. extended to Air Tanzania Company Limited (ATCL) as our clients, notably As promised in the previous in-flight passengers. ATCL with its entire magazine, we have increased the staff acknowledge and reiterate the frequency of Dodoma and Tabora company’s topmost commitment to all flights taking into account that this Nairobi (Kenya), Entebbe (Uganda) our passengers and other customers route would link the Capital City and Bujumbura (Burundi). as we mark the New Year. of Dodoma with other towns or Two more Bombardier CS 300 destinations in Western Tanzania and aircraft scheduled for mid-range It is in this light that, we, the the Lake Zone. routes in Africa are expected to enter management and entire staff of the skies; these two equipments will ATCL continue to give and provide I feel proud to say that our Airline has link Dar es Salaam with other regional highly improved flight services to all increased efficiency counting at 85 routes of Lubumbashi (DR Congo), customers as we value the precious percent (85%) On Time Performance Lagos (Nigeria), Harare (Zimbabwe), support they had extended to us (OTP). This means we fly on time Lusaka (Zambia) and Accra (Ghana). -

Sona Jobarteh Sona Jobarteh Vocals, Kora Derek Johnson Guitar, Vocals

2019 20:00 19.11.Salle de Musique de Chambre Mardi / Dienstag / Tuesday Autour du monde Sona Jobarteh Sona Jobarteh vocals, kora Derek Johnson guitar, vocals Mamadou Sarr percussion, vocals Sidiki Jobarteh balafon Andi McLean bass, vocals Westley Joseph cajón, vocals ~90’ without intermission De Kamelleknécheler Martin Fengel Sona Jobarteh, la kora au féminin Vincent Zanetti L’influence du grand frère Au départ, c’est l’histoire de deux enfants, frère et sœur métisses nés de pères différents. Onze ans les séparent, mais ils partagent un même don évident pour la musique. L’aîné s’appelle Tunde Jegede, il est le fils d’Emmanuel Taiwo Jegede, un artiste nigérian en résidence au Keskidee Center de Londres, le premier centre de culture négro-africaine de Grande-Bretagne. Environnement propice pour cet enfant au talent précoce, qui y fait la rencontre de personnalités aussi marquantes que Bob Marley et Angela Davis, entre autres. Il en retire une vraie passion pour les musiques africaines, tandis que de son grand-père maternel, organiste d’église, il hérite l’amour de l’œuvre de Jean-Sébastien Bach. La cadette s’appelle Maya Sona, elle est la fille de Sanjally Jobarteh, un griot gambien virtuose de la kora, dont le propre père se trouve être Amadu Bansang Jobarteh, un des plus fameux maîtres de cet instrument en Gambie. C’est auprès de lui, justement, que le jeune Tunde Jegede s’initie à la kora depuis l’âge de dix ans. La petite fille grandit à Londres, mais dès sa plus tendre enfance, elle établit un lien très fort avec sa famille gambienne qu’elle visite régulièrement avec son frère. -

Sona Jobarteh

SONA JOBARTEH Sona Jobarteh is the first female Kora virtuoso to come from a west African Griot family. Breaking away from tradition, she is a pioneer in an ancient male-dominated hereditary tradition that has been exclusively handed down from father to son for the past seven centuries. Reputed for her skill as an instrumentalist, distinctive voice, infectious melodies and her grace onstage, Sona has rapidly risen to international success following the release of her critically acclaimed album “Fasiya” (Heritage) in 2011. The Kora (a 21-stringed African harp) is one of the most important instruments belonging to the Manding peoples of West Africa (Gambia, Senegal, Mali, Guinea and Guinea-Bissau). It belongs exclusively to griot families (hereditary musical families), and only those who are born into one of these families have the right to take up the instrument professionally. Sona, who was born into one of the five principal Griot families, has become the first female to take up this instrument professionally in a male tradition that dates back over seven centuries. Sona's family carries a heavy reputation for renowned Kora masters, notably her grandfather Amadu Bansang Jobarteh who was an icon in Gambia’s cultural and musical history, and her cousin Toumani Diabaté who is renowned for his mastery of the Kora. In recent years Sona has quickly been rising to international success, headlining major festivals around the world in Brazil, India, South Korea, Ghana, Mexico, Tanzania, Cote D’Ivoire, Lithuania, Poland and Malaysia just to name a few. Sona and her music has the unique ability to touch audiences from all backgrounds and cultures. -

Sona Jobarteh »Flying«

Musikpoeten 2 Sona Jobarteh »Flying« Samstag 16. November 2019 20:00 Bitte beachten Sie: Ihr Husten stört Besucher und Künstler. Wir halten daher für Sie an den Garderoben Ricola-Kräuterbonbons bereit. Sollten Sie elektronische Geräte, insbesondere Mobiltelefone, bei sich haben: Bitte schalten Sie diese zur Vermeidung akustischer Störungen unbedingt aus. Wir bitten um Ihr Verständnis, dass Bild- und Tonaufnahmen aus urheberrechtlichen Gründen nicht gestattet sind. Wenn Sie einmal zu spät zum Konzert kommen sollten, bitten wir Sie um Verständnis, dass wir Sie nicht sofort einlassen können. Wir bemühen uns, Ihnen so schnell wie möglich Zugang zum Konzertsaal zu gewähren. Ihre Plätze können Sie spätestens in der Pause einnehmen. Bitte warten Sie den Schlussapplaus ab, bevor Sie den Konzertsaal verlassen. Es ist eine schöne und respektvolle Geste den Künstlern und den anderen Gästen gegenüber. Mit dem Kauf der Eintrittskarte erklären Sie sich damit einverstanden, dass Ihr Bild möglicherweise im Fernsehen oder in anderen Medien ausgestrahlt oder veröffentlicht wird. Vordruck/Lackform_1920.indd 2-3 17.07.19 10:18 Musikpoeten 2 Sona Jobarteh kora, voc Sidiki Jobarteh balafon, voc Derek Johnson g, voc Mamadou Sarr perc, voc Andi McLean b, voc Westley Joseph dr, voc »Flying« Samstag 16. November 2019 20:00 Keine Pause Ende gegen 21:30 Dieses Konzert wird auch live auf philharmonie.tv übertragen. Der Livestream wird unterstützt durch JTI. PROGRAMM »Flying« Jarabi Mamamuso Gainaako Kaira Gambia Kanu Bannaya Alle Songs sind von Sona Jobarteh komponiert. 2 La Griotte! – Die Kora-Virtuosin Sona Jobarteh & Band Die meistverbreitete Legende darüber, wie die Kora in die Welt gekommen ist, spielt im heutigen westfafrikanischen Guinea- Bissau. -

Full Press Release PDF 191.77 Kb

JUST ANNOUNCED Sona Jobarteh Sun 28 Nov 2021, Milton Court Concert Hall, 6.30pm & 8.30pm Tickets £25 – 35 plus booking fee Sona Jobarteh, Gambian singer and expert player of the kora, a 21-stringed African harp, makes her Barbican programme debut this November alongside her band, giving two performances at Milton Court Concert Hall. Sona is the first female professional kora virtuoso in the centuries-old West African griot tradition, which brings together music, storytelling and oral history. She is a pioneer in this male-dominated hereditary tradition that has been exclusively handed down from father to son for the past seven centuries. Her lineage carries many renowned Kora masters including her cousin Toumani Diabaté and her grandfather Amadu Bansang Jobarteh after whom she has named her Academy in Gambia which she founded in 2016. It is the first school to deliver a mainstream academic curriculum at a high level; providing a platform for her to become a powerful speaker in the areas of social development and educational reform in Africa. Sona Jobarteh’s on stage skills as an instrumentalist, singer and composer are testament to her success as an international artist; her forthcoming new album has been heralded by her song The Gambia that has attracted over 18 million listeners. Produced by the Barbican On sale to Barbican patrons and members on Wed 11 August 2021 On general sale on Fri 13 August 2021 Find out more Klein Sun 30 Jan 2022, Barbican Hall, 7.30pm Tickets £12.50 – 15 plus booking fee Avant-garde British composer and multi-disciplinary artist Klein will bring a new thrilling, inimitable live show to the Barbican in January 2022. -

Midge Ure African Night Fever: Sona Jobarteh Martin Barre Snowboy & the Latin Section Exhibition on Screen Le Vent Du Nord

SPARKLING ARTS EVENTS IN THE HEART OF SHOREHAM SUMMER 2016 ANIMALS & FRIENDS HAYSEED DIXIE PENTANGLE & MAGNA CARTA MIDGE URE AFRICAN NIGHT FEVER: SONA JOBARTEH MARTIN BARRE SNOWBOY & THE LATIN SECTION EXHIBITION ON SCREEN LE VENT DU NORD ROPETACKLECENTRE.CO.UK SUMMERROPETACKLE 2016 CAFÉ ropetacklecentre.co.uk BOX OFFICE: 01273 464440 WELCOME WELCOME TO Open Monday – Saturday: 10am – 4.30pm Contact: [email protected] The Ropetackle Café is located in the foyer of Welcome to our summer programme, full of amazing music, comedy, Ropetackle Arts Centre. We serve a delicious theatre, talks, family events, and much more, all running from May – range of teas, coffees, and soft drinks, plus a August 2016. An award-winning venue, we are delighted to offer another wonderful menu of freshly made sandwiches, exceptional programme of events with something for everyone to enjoy. paninis, soups, jacket potatoes, scrumptious During the day our café is open and serving many delectable delights, and cakes and more. The large, light and airy our pre-show meals offer a great start to any event (see opposite page for Ropetackle foyer is the perfect place to enjoy more details). As a charitable trust staffed almost entirely by volunteers, a relaxing coffee, meet with friends for a light donations are vital to covering our running costs and programme delivery, lunch, or get some work done with our free and our Friends scheme is a great way to support Ropetackle and join our wi-fi. growing community (see page 61 for details). Our friendly atmosphere, intimate performance space, and first-class programming makes every We also offer delicious pre-show dining before event an extra special experience, and we look forward to welcoming you to Ropetackle events taking place on Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays. -

Edinburgh International Festival Announces 2021 Programme

MEDIA RELEASE Edinburgh International Festival Announces 2021 Programme Jenna Reid (fiddle), Su-a Lee (cello) and Iain Sandilands (percussion) perform in the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh to celebrate the launch of the 2021 Edinburgh International Festival programme. © Ryan Buchanan MEDIA IMAGES AVAILABLE HERE VIDEO TRAILER AVAILABLE HERE B-ROLL, INCLUDING AN INTERVIEW WITH FESTIVAL DIRECTORS AVAILABLE HERE Classical music: Nicola Benedetti, Sol Gabetta, Sir Andrew Davis, Valery Gergiev, Daniil Trifonov, Marin Alsop, Isata Kanneh-Mason, Sir Simon Rattle, William Eddins, Kazushi Ono, Thomas Søndergård, Elim Chan, Dalia Stasevska and more Opera: Dorothea Röschmann, Renée Fleming, Golda Schultz, Joyce DiDonato, Danielle de Niese, Thomas Quasthoff, David Butt Philip, Catriona Morison and more Contemporary music: Anna Meredith, Damon Albarn, Laura Mvula, black midi, The Snuts, Karine Polwart, The Staves, Nadine Shah, The Comet is Coming, Tune-Yards, Caribou, Floating Points and more Theatre & Dance: Enda Walsh, Domhnall Gleeson, Alan Cumming, Akram Khan, Inua Ellams, Saul Williams, Hollie McNish, Hannah Lavery, Alice Ripoll, Omar Rajeh, Gregory Maqoma, Janice Parker and more Scottish companies and ensembles: National Theatre of Scotland, Scottish Opera, Royal Scottish National Orchestra, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Curious Seed, RURA, Kinnaris Quintet, Breabach and more eif.co.uk 2 June, Edinburgh: Edinburgh International Festival, the world’s leading performing arts festival, pioneers the return of live performance in Scotland from 7 – 29 August with a diverse programme of UK and international artists. This return to live performance marks a significant turning point for Scotland's cultural sector by providing a platform for artists to return to the stage after over a year. -

November 13 - 16 | Indianapolis, in |Indianapolis, -16 13 November Pasic Program

november 13 -16 |indianapolis, in pasic program Pasic table of contents 6 PAS President’s Welcome 8 Special Thanks 12 Area Map and Restaurant Guide 14 Convention Center Map 16 Exhibitors by Name 17 Exhibit Hall Map 18 Exhibitors by Category 22 Exhibitor Company Descriptions 36 11.13.19 Schedule of Events 37 11.14.19 New Music/Research Presents Events 38 11.14.19 Schedule at a Glance 40 11.14.19 Schedule of Events 42 11.15.19 Schedule at a Glance 44 11.15.19 Schedule of Events 48 11.16.19 Schedule at a Glance 54 11.16.19 Schedule of Events 60 About the Artists 90 PAS Corporate Sponsors 91 PASIC 2019 Advertisers 92 PAS History 94 PAS 2019 Awards 97 PAS Hall of Fame expa nd your pasic experience rudiment training 40 PAS Rudiments. drum set. keyboard. Come test your knowledge of the rudiments this year at PASIC. Become certified by PAS by participating in an interactive training session with top percussion educators. evening concerts full cash bar available Wednesday 8PM - Nate Smith + KINFOLK Thursday 8PM - Third Coast Percussion Friday 8PM - Tambuco Percussion Ensemble Saturday 5:30PM - Michel Camilo Trio with Dafnis Prieto & Eduardo Belo late night hangs westin lobby and bar - 10pm Thursday Night - Marimba/Vibe “Open Mic” Friday Night - Jazz Quartet with Surprise Guest Drummers world's fastest drummer booth 1309 closing drum cricle Serpentine lobby - 4pm find out more on Attendify the official pasic app PASIC® is a program of the Percussive Arts Society, whose mission is to inspire, educate, and support percussionists and drummers throughout the world.