TABLE of CONTENTS – Chapter 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Campsite Impact in the Wilderness of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks Thirty Years of Change

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Campsite Impact in the Wilderness of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks Thirty Years of Change Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SEKI/NRTR—2013/665 ON THE COVER Examples of campsites surveyed in the late 1970s and again in 2006-2007. In a clockwise direction, these sites are in the Striped Mountain, Woods Creek, Sugarloaf, and Upper Big Arroyo areas in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. Photographs by: Sandy Graban and Bob Kenan, Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. Campsite Impact in the Wilderness of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks Thirty Years of Change Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SEKI/NRTR—2013/665 David N. Cole and David J. Parsons Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station 790 East Beckwith Avenue Missoula, Montana 59801 January 2013 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series provides contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. -

VGP) Version 2/5/2009

Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) VESSEL GENERAL PERMIT FOR DISCHARGES INCIDENTAL TO THE NORMAL OPERATION OF VESSELS (VGP) AUTHORIZATION TO DISCHARGE UNDER THE NATIONAL POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM In compliance with the provisions of the Clean Water Act (CWA), as amended (33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq.), any owner or operator of a vessel being operated in a capacity as a means of transportation who: • Is eligible for permit coverage under Part 1.2; • If required by Part 1.5.1, submits a complete and accurate Notice of Intent (NOI) is authorized to discharge in accordance with the requirements of this permit. General effluent limits for all eligible vessels are given in Part 2. Further vessel class or type specific requirements are given in Part 5 for select vessels and apply in addition to any general effluent limits in Part 2. Specific requirements that apply in individual States and Indian Country Lands are found in Part 6. Definitions of permit-specific terms used in this permit are provided in Appendix A. This permit becomes effective on December 19, 2008 for all jurisdictions except Alaska and Hawaii. This permit and the authorization to discharge expire at midnight, December 19, 2013 i Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 William K. Honker, Acting Director Robert W. Varney, Water Quality Protection Division, EPA Region Regional Administrator, EPA Region 1 6 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, Barbara A. -

The ANZA-BORREGO DESERT REGION MAP and Many Other California Trail Maps Are Available from Sunbelt Publications. Please See

SUNBELT WHOLESALE BOOKS AND MAPS CALIFORNIA TRAIL MAPS www.sunbeltpublications.com ANZA-BORREGO DESERT REGION ANZA-BORREGO DESERT REGION MAP 6TH EDITION 3RD EDITION ISBN: 9780899977799 Retail: $21.95 ISBN: 9780899974019 Retail: $9.95 Publisher: WILDERNESS PRESS Publisher: WILDERNESS PRESS AREA: SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA AREA: SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA The Anza-Borrego and Western Colorado Desert A convenient map to the entire Anza-Borrego Desert Region is a vast, intriguing landscape that harbors a State Park and adjacent areas, including maps for rich variety of desert plants and animals. Prepare for Ocotillo Wells SRVA, Bow Willow Area, and Coyote adventure with this comprehensive guidebooks, Moutnains, it shows roads and hiking trails, diverse providing everything from trail logs and natural history points of interest, and general topography. Trip to a Desert Directory of agencies, accommodations, numbers are keyed to the Anza-Borrego Desert Region and facilities. It is the perfect companion for hikers, guide book by the same authors. campers, off-roaders, mountain bikers, equestrians, history buffs, and casual visitors. The ANZA-BORREGO DESERT REGION MAP and many other California trail maps are available from Sunbelt Publications. Please see the following listing for titles and details. s: catalogs\2018 catalogs\18-CA TRAIL MAPS.doc (800) 626-6579 Fax (619) 258-4916 Page 1 of 7 SUNBELT WHOLESALE BOOKS AND MAPS CALIFORNIA TRAIL MAPS www.sunbeltpublications.com ANGEL ISLAND & ALCATRAZ ISLAND BISHOP PASS TRAIL MAP TRAIL MAP ISBN: 9780991578429 Retail: $10.95 ISBN: 9781877689819 Retail: $4.95 AREA: SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA AREA: NORTHERN CALIFORNIA An extremely useful map for all outdoor enthusiasts who These two islands, located in San Francisco Bay are want to experience the Bishop Pass in one handy map. -

Science Symposium: Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks Science Symposium: Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks November 9-10, 2016 ON THIS PAGE Photograph of symposium participants listening to a talk at Saint Anthony Retreat, Three Rivers, California. ON THE COVER Photographs from top left to bottom right: Bullfrog Lake from Kearsarge Pass, Kings Canyon NP (Joan Dudney); Crescent Meadow, Sequoia NP (Evan Wolf); burned forest in Yosemite National Park’s Illilouette Creek Basin (Scott Stephens); Sierra Bighorn Sheep ewe being released (California Department of Fish and Wildlife); and mountain yellow-legged frogs (Roland Knapp). Science Symposium: Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks November 9-10, 2016 National Park Service Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks 47050 Generals Highway Three Rivers, California 93271 This report is available in digital format from: https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2238518. Please cite this report as: National Park Service. 2017. Science Symposium: Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. November 9-10, 2016. Three Rivers, California. Linda Mutch (Sierra Nevada Network) and Koren Nydick, Ginger Bradshaw, and Theresa Fiorino (Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks) compiled and edited this report. i Contents Page Figures ................................................................................................................................................... vi Photographs .......................................................................................................................................... -

Stock Users Guide to the Wilderness of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks a Tool for Planning Stock-Supported Wilderness Trips

Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior National Parks Stock Users Guide to the Wilderness of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks A tool for planning stock-supported wilderness trips SEQUOIA & KINGS CANYON NATIONAL PARKS Wilderness Office 47050 Generals Highway Three Rivers, California 93271 559-565-3766 [email protected] www.nps.gov/seki/planyourvisit/wilderness.htm Revised May 6th, 2021 EAST CREEK .............................................................................. 19 TABLE OF CONTENTS SPHINX CREEK .......................................................................... 19 INTRO TO GUIDE ........................................................................ 2 ROARING RIVER ....................................................................... 19 LAYOUT OF THE GUIDE............................................................. 3 CLOUD CANYON ....................................................................... 20 STOCK USE & GRAZING RESTRICTIONS: DEADMAN CANYON ................................................................ 20 KINGS CANYON NATIONAL PARK .................................... 4 SUGARLOAF AND FERGUSON CREEKS ................................. 21 SEQUOIA NATIONAL PARK ................................................ 6 CLOVER AND SILLIMAN CREEKS .......................................... 23 MINIMUM IMPACT STOCK USE ................................................ 8 LONE PINE CREEK .................................................................... 23 MINIMUM -

Hiking Baxter Pass Trail

Inyo National Forest Baxter Pass Trail Baxter Pass Trail climbs over 6,000 vertical feet from the desert to the crest of the Sierra Nevada. Beginning at an elevation of 6,000 feet, it ascends to 12,300 foot Baxter Pass in 7.2 miles. At the top of the pass, the trail enters Kings Canyon National Park. Due to its challenging nature, Baxter Pass Trail is visited relatively infrequently. It is steep, rugged and infrequently maintained. The first 3.5 miles of the trail pass through an old burn area. In this area, the trail is occasionally blocked or obscured by fallen trees or brush. Baxter Pass Trail is not recommended for stock. Trailhead Facilities: Water: No Camping Options: Nearest developed campground is Independence Creek Campground, located 1 mile west of Independence, CA, on Market Street. On The Trail: Food Storage: Food, trash and scented items must be stored in bear-resistant containers or counter-balanced 15 feet above the ground and 10 feet horizontally from a tree trunk. Suitable trees are not available in most locations, so bear-resistant containers are strongly recommended. Camping: Use existing campsites. Camping is prohibited within 25 feet of the trail and within 100 feet of water . Human Waste: Bury human waste 6”-8” deep in soil, at least 100 ft from campsites, trails, and water. Access: Campfires: Campfires are prohibited above 10,400 ft. From Highway 395, 2 miles north of Independence, CA: elevation. Turn west onto Fish Hatchery Rd. Pets: Pets must be under control at all times. After 1.2 miles, turn right at fork in road. -

Mineral Resource Potential of the John Muir Wilderness, Fresno, Inyo, Madera, and Mono Counties, California

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP MF-1185-C UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MINERAL RESOURCE POTENTIAL OF THE JOHN MUIR WILDERNESS, FRESNO, INYO, MADERA, AND MONO COUNTIES, CALIFORNIA SUMMARY REPORT By 2 E. A. du Bray1, D. ~ Dellinger1, H. W. ~ver 1 , M. F. Diggl~l, Fredrick L. J~ , Horace K. 'lburber , Richard W. Morris , Thomas J. Peters , and David s. Lindsey STUDIES RELATED TO WILDERNESS Under the provisions of the Wilderness Act (Public Law 88-577, September 3, 1964) and the Joint Conference Report on Senate Bill 4, 88th Congress, the U.S. Geological Survey and the U.S. Bureau of Mines have been conducting mineral surveys of wilderness and primitive areas. Areas officially designated as "wilderness," "wild," or "canoe" when the act was passed were incorporated into the National Wilderness Preservation System, and some of them are presently being studied. The act provided that areas under consideration for wilderness designation should be studied for suitability for incorporation into the Wilderness System. The mineral surveys constitute one aspect of the suitability studies. The act directs that the results of such surveys are to be made available to the public and be submitted to the President and the Congress. This report discusses the results of a mineral survey of the John Muir Wilderness, Inyo and Sierra Na tional Forests, Fresno, lnyo, Madera, and Mono Counties, California. The area was established as a wilderness by Public Law 88-577, September 3, 1964. SUMMARY The U.S. Bureau of Mines arj the U.S. Geological Survey identified many areas of the John Muir Wilderness as having marginal and subeconomic resources of tungsten, molybdenum, copper, gold, and silver. -

Notices Federal Register Vol

35317 Notices Federal Register Vol. 65, No. 107 Friday, June 2, 2000 This section of the FEDERAL REGISTER developing this program, the Secretary diverse groups served by USDA, contains documents other than rules or is required to establish a NOSB. The membership shall include, to the extent proposed rules that are applicable to the purpose of the NOSB is to assist in the practicable, individuals with public. Notices of hearings and investigations, development of a proposed National demonstrated ability to represent committee meetings, agency decisions and List of Approved and Prohibited minorities, women, and persons with rulings, delegations of authority, filing of petitions and applications and agency Substances and to advise the Secretary disabilities. statements of organization and functions are on other aspects of the National Organic The information collection examples of documents appearing in this program. requirements concerning the section. The current NOSB has made nomination process have been recommendations to the Secretary previously cleared by the Office of regarding the establishment of the initial Management and Budget (OMB) under DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE organic program. It is anticipated that OMB Control No. 0505±0001. the NOSB will continue to make Dated: May 26, 2000. Agricultural Marketing Service recommendations on various matters Sharon Bomer Lauritsen, [TM±00±05] including recommendations on Acting Deputy Administrator, Transportation substances it believes should be and Marketing. Nominations for Members of the permitted to be used or prohibited for [FR Doc. 00±13784 Filed 6±1±00; 8:45 am] National Organic Standards Board use in organic production and handling. BILLING CODE 3410±02±P The NOSB is required to be composed AGENCY: Agricultural Marketing Service, of various individuals including owners USDA. -

NATIONAL PARK - CALIFORNIA UNITED STATES Historic Events DEPARTMENT of the Kings INTERIOR 1862 First White Man of Record Entered Area

I II NATIONAL PARK - CALIFORNIA UNITED STATES Historic Events DEPARTMENT OF THE Kings INTERIOR 1862 First white man of record entered area. Joseph Hardin Thomas discovered the General Grant Tree, then unnamed. HAROLD L. ICKES, Secretary Canyon OPEN NATIONAL 1867 General Grant Tree measured; named by ALL Lucretia P. Baker, member of pioneer YEAR PARK family of the district. CALIFORNIA 1870 First settlers occupied Fallen Monarch MULE DEER ARE SEEN EVERYWHERE huge hollow log. NATIONAL PARK SERVICE IN THE PARK NEWTON B. DRURY, Director 1872 The Gamlin brothers built log house now COKTEi^rs known as Gamlin Pioneer Cabin and INGS CANYON NATIONAL rates the two great South Fork and used as museum. K PARK was created by act of Middle Fork Canyons. The Middle North Dome ........ Cover Congress, March 4,1940. It comprises Fork is reached only by trail by cross Cover photo by Laval Co., Inc. 710 square miles of superlative moun ing over Granite Pass or Cartridge A Description of Kings Canyon by 1878 Preemption claim surrounding the Gen eral Grant Tree surrendered to the Gov tain scenery in the heart of the Sierra Pass, by traversing the 12,000-foot John Muir (1838-1914) .... 4 ernment by Israel Gamlin. Nevada and three groves of giant se Mather Pass on the John Muir Trail, The Groves 6 quoias. In the creation of this park, the or by descending from road end at Forests and Flowers 6 Crabtree Camp on the North Fork of 1890 General Grant National Park (now Gen former General Grant National Park, Wildlife 6 eral Grant Grove Section of Kings Can with the addition of the Redwood the Kings into Tehipite Valley to Fishing 7 yon National Park) created by act of Mountain area, became the General view the famous Tehipite Dome. -

Public Law 98-425 An

PUBLIC LAW 98-425-SEPT. 28, 1984 98 STAT. 1619 Public Law 98-425 98th Congress An Act Sept. 28, 1984 Entitled the "California Wilderness Act of 1984". [H.R. 1437] Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That this title may California Wilderness Act be cited as the "California Wilderness Act of 1984". of 1984. National TITLE I Wilderness Preservation System. DESIGNATION OF WILDERNESS National Forest System. SEC. 101. (a) In furtherance of the purposes of the Wilderness Act, National parks, the following lands, as generally depicted on maps, appropriately monuments, etc. referenced, dated July 1980 (except as otherwise dated) are hereby 16 USC 1131 designated as wilderness, and therefore, as components of the Na note. tional Wilderness Preservation System- (1)scertain lands in the Lassen National Forest, California,s which comprise approximately one thousand eight hundred acres, as generally depicted on a map entitled "Caribou Wilder ness Additions-Proposed", and which are hereby incorporated in, and which shall be deemed to be a part of the Caribou Wilderness as designated by Public Law 88-577; 16 USC 1131 (2)s certain lands in the Stanislaus and Toiyabe Nationals note. 16 USC 1132 Forests, California, which comprise approximately one hundred note. sixty thousand acres, as generally depicted on a map entitled "Carson-Iceberg Wilderness-Proposed", dated July 1984, and which shall be known as the Carson-Iceberg Wilderness: Pro vided, however, That the designation of the Carson-Iceberg Wil derness shall not preclude continued motorized access to those previously existing facilities which are directly related to per mitted livestock grazing activities in the Wolf Creek Drainage on the Toiyabe National Forest in the same manner and degree in which such access was occurring as of the date of enactment of this title; (3)scertain lands in the Shasta-Trinity National Forest, Cali 16 USC 1132 fornia, which comprise approximately seven thousand three note. -

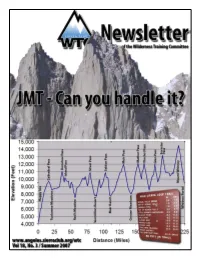

Wtc 1803C.Pdf

WTC Officers WTC Says Congratulations! By Kay Novotny See page 8 for contact info WTC Chair Scott Nelson Long Beach Area Chair KC Reid Area Vice Chair Dave Meltzer Area Trips Mike Adams Area Registrar Jean Konnoff WTC would like to congratulate 2 of their Orange County leaders on their recognition at the annual Area Chair Sierra Club Angeles Chapter Awards Edd Ruskowitz Banquet. This event took place on May 6th, 2007, Area Vice Chair at the Brookside Country Club in Pasadena. Barry John Cyran Holchin, right, who is an “M”rated leader, and who WTC Outings Chair and Area Trips divided his time last year between Long Tom McDonnell Beach/South Bay’s WTC groups 2 and 3, received a Area Registrar conservation service award. These awards are given Kirt Smoot to Sierra Club members who deserve special San Gabriel Valley recognition for noteworthy service they have ren- Area Chair dered to the Angeles Chapter. Dawn Burkhardt Bob Beach, left, another “M” rated leader, who is Area Vice Chair Shannon Wexler Long Beach/South Bay’s Group 1 assistant leader, Area Trips received the prestigious Chester Versteeg Outings Helen Qian Plaque, which is the highest outings leadership Area Registrar award conferred by the Angeles Chapter. It is James Martens awarded to a Sierra Club member who has pro- vided long-term and outstanding leadership in furthering the enjoyment and safety of the outings program. West Los Angeles Congratulations, Barry and Bob! We all appreciate your hard work and dedication to the WTC program. Area Chair Gerard Lewis Area Vice Chair Kathy Rich Area Trips Graduations Marc Hertz Area Registrar Graduations are currently scheduled for October 20 and 21 at Indian Cove in Joshua Tree National Park. -

Peak Bagging

Peak Bagging: (complete award size: 8" x 6") Program and Awards Offered by the HIGH ADVENTURE TEAM Greater Los Angeles Area Council Boy Scouts of America The High Adventure Team of the Greater Los Angeles Area Council-Boy Scouts of America is a volunteer group of Scouters which operates under the direction of GLAAC-Camping Services. Its mission is to develop and promote outdoor activities within the Council and by its many Units. It conducts training programs, sponsors High Adventure awards, publishes specialized literature such as Hike Aids and The Trail Head and promotes participation in summer camp, in High Adventure activities such as backpacking, peak climbing, and conservation, and in other Council programs. Anyone who is interested in the GLAAC-HAT and its many activities is encouraged to direct an inquiry to the GLAAC-Camping Services or visit our web site at http://www.glaac-hat.org/. The GLAAC-HAT meets on the evening of the first Tuesday of each month at 7:30 pm in the Cushman Watt Scout Center, 2333 Scout Way, Los Angeles, CA 90026. These meetings are open to all Scouters. REVISIONS Jan 2016 General revision. Peak Bagger Peak list: Tom Thorpe removed Mt. San Antonio, added Blackrock Dick Rose Mountain. Mini-Peak Bagger list: removed Dawson Peak and Pine Mountain No. 1. Renamed "Suicide Peak" to "Suicide Rock". Updated "General Requirements" section. Jan 2005 New document incorporating Program Announcements 2 and 3. Prepared by Lyle Whited and composed by John Hainey. (Mt. Markham, summit trail) Peak Bagging Program and Awards