Hunting Magic, Maintenance Ceremonies and Increase Sites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Heritage Series

VOLUME 4 PART 2 MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM CULTURAL HERITAGE SERIES 17 OCTOBER 2008 © The State of Queensland (Queensland Museum) 2008 PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226 Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum CHAPTER 4 HISTORICAL MUA ANNA SHNUKAL Shnukal, A. 2008 10 17: Historical Mua. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Cultural Heritage Series 4(2): 61-205. Brisbane. ISSN 1440-4788. As a consequence of their different origins, populations, legal status, administrations and rates of growth, the post-contact western and eastern Muan communities followed different historical trajectories. This chapter traces the history of Mua, linking events with the family connections which always existed but were down-played until the second half of the 20th century. There are four sections, each relating to a different period of Mua’s history. Each is historically contextualised and contains discussions on economy, administration, infrastructure, health, religion, education and population. Totalai, Dabu, Poid, Kubin, St Paul’s community, Port Lihou, church missions, Pacific Islanders, education, health, Torres Strait history, Mua (Banks Island). -

The Archaeological Heritage of Christianity in Northern Cape York Peninsula

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by ResearchOnline at James Cook University The Archaeological Heritage of Christianity in Northern Cape York Peninsula Susan McIntyre-Tamwoy Abstract For those who have worked in northern Cape York Peninsula and the Torres Strait, the term ‘coming of the light’ will have instant meaning as the symbolic reference to the advent of Christianity amongst Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. This paper explores the approaches that anthropologists and archaeologist have adopted in exploring the issues around Christianity, Aboriginal people, missions and cultural transformations. For the most part these disciplines have pursued divergent interests and methodologies which I would suggest have resulted in limited understandings of the nature and form of contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identity and a lack of appreciation of the material culture that evidences this transformation. Through an overview of some of the work undertaken in the region the paper explores the question ‘Can we really understand contemporary identity and the processes that have led to its development without fully understanding the complex connections between place and people and historical events and symbolic meaning, in fact the ‘social landscape of Aboriginal and Islander Christianity.’ This paper was presented in an earlier form at the Australian Anthropological Society 2003 Annual Conference held in Sydney. KEYWORDS: Archaeology, Christian Missions, Cape York Peninsula Introduction dominated profession, are squeamish about the impact of western religions on indigenous culture. In this paper I consider the overlap between • Thirdly, given that historical archaeology in Australia anthropological enquiry and archaeology in relation to has been heavily reliant on the investigation of built the Christian Mission period in the history of Cape York structures (Paterson & Wilson 2000:85) the nature of Peninsula. -

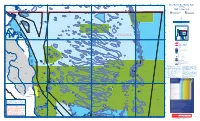

Map1-Editionv-Cape-York.Pdf

142°35'E 142°40'E 142°45'E 142°50'E 142°55'E 143°00'E 143°05'E 143°10'E 143°15'E 143°20'E 143°25'E 143°30'E 143°35'E 143°40'E 143°45'E 143°50'E 143°55'E 144°00'E 144°05'E 144°10'E 144°15'E L Great Barrier Reef Marine Parks Lacey Island Jardine Rock Nicklin Islet Forbes Head Zoning Mt Adolphus (Mori) Island Morilug Islet A do Kai-Damun Reef lph us Johnson Islet S S ' ' 0 0 MAP 1 - Cape York 4 Akone 4 ° Quetta Rock ° 0 L Islet 0 1 C 1 York Island L Mid Rock ha nn 10-807 # # # # # # # Eborac Island (NP) e # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # l # 10°41.207'S Cape York Meggi-Damun Reef 10-348 10-387 L 10-315 10-381 # Sana Rock North Brother North Ledge 10-350 Sextant Rock 10-349 E L# 10-326 10-322 ' 10-313 L 10-325 2 # Tree Island 10-316 10-382 3 Ida Island Middle South Ledge 0 . 10-384 10-314 Bush Islet 10-317 Brother 10-327 5 5 a 10-321 10-323 ° # Albany Rock L L 3 Little Ida Island 4 # L 1 10-386 10-802# Mai Islet 10-320 # L 9 2 Tetley 10-805 10-385 4 t b Pitt Rock 10-319 South - n # 0 0 i d Island 10-351 1 3 o # 10-389 4 P Brother MNP-10-1001 - g # 10-352 S 0 10-324 10-392 S ' r 10-390 ' 1 # 10-443 u Albany Island 5 c 5 b 4 4 a 10-318 ° Fly Point ° n # 10-393 0 10-353 0 s # 10-354 1 O L Ulfa Rock10-328 Triangle Reef 1 10-434 10-355 10-391 # 10-397 Ariel Bank10-329 10-394 ´ 10-356 10-396 Scale 1 : 250 000 L 10-299 10-398 E 10-330 ' # # # 5 10-804 Harrington Shoal # Ch 0 10-399 andogoo Po # 0 5 10 15 20 km in 10-331 9 10-395 t . -

The Aboriginal Miners and Prospectors of Cape York Peninsula 1870 to Ca.1950S

Journal of Australasian Mining History, Vol. 16, October 2018 The Aboriginal miners and prospectors of Cape York Peninsula 1870 to ca.1950s By GALIINA ELLWOOD James Cook University t is a common assumption among many Australian historians that frontier violence between Aboriginal peoples and colonisers was the norm. This, it is believed, was I inevitably followed by resistance to invasion being subsequently crushed over varying periods of time and the remnant of traditional owners being then assimilated into the lowest rung of the European culture and economy, while being deprived of their civil rights by ‘protection’ Acts.1 This is true of some times and places, but is not true everywhere, and particularly not on Queensland’s Cape York Peninsula where Aboriginal people were miners and prospectors of importance to the Queensland economy. So important were they that officials were apt to wink at their independence from government controls, an attitude helped by the isolation of the area from the control of officials in the bigger towns and Brisbane. Aboriginal prospectors and miners in the area found goldfields and tinfields, mined for tin, gold and wolfram either by themselves, for an employer, or with a white ‘mate’. Further, they owned or worked mills and prospecting drill plants, and undertook ancillary activities such as hauling supplies. What is more, their families have continued mining up to the present day. Despite their considerable role in the industry, they have been written out of the mining history of Cape York, a trend which has unfortunately continued up to today. This article, along with earlier work2 is intended to redress the omission. -

The Falkland Islands As a Scientific Nexus for Charles Darwin, Joseph Hooker, Thomas Huxley, Robert Mccormick and Bartholomew Sulivan, 1833-1851

Reprinted from -The Falkland Islands Journal 2020 11(4): 15-37 THE FALKLAND ISLANDS AS A SCIENTIFIC NEXUS FOR CHARLES DARWIN, JOSEPH HOOKER, THOMAS HUXLEY, ROBERT MCCORMICK AND BARTHOLOMEW SULIVAN, 1833-1851. by Phil Stone Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and Joseph Hooker (1817–1911) became two of the best- known figures in 19th century British science and have enduring reputations. For both men, the starting point of their careers was a round-the-world voyage on a Royal Navy vessel: 1831-1836 aboard HMS Beagle for Darwin, 1839–1843 aboard HMS Erebus for Hooker. Both ships spent time in the Falkland Islands engaged on survey and scientific work and Darwin and Hooker are both credited with originating research themes there in the fields of zoology, botany and geology. Appropriately, both men are celebrated and pictured in The Dictionary of Falklands Biography. The circumstances in which they travelled were very different, but both enjoyed certain advantages. Darwin was supernumerary to Beagle’s crew and was effectively the guest of the captain, Robert Fitzroy (1805–1865). As such he had considerable liberty of activity beyond the confines of the ship (Figure 1). Hooker held only a junior Naval commission as assistant surgeon on Erebus but enjoyed good social connections, an influential father, and had the cooperative support of the captain, James Clark Ross (1800–1862), in pursuit of his botanical research. Of course, neither man operated in isolation and what they were able to achieve was strongly influenced by their interactions with other members of the ships’ complements. Darwin had the financial backing of a wealthy family and was able to employ a personal assistant, Syms Covington, whose role has been recently described in Falkland Islands Journal by Armstrong (2019). -

A Meeting with Old Man Crocodile on Cape York Peninsula

Talking with Ghosts: A Meeting with Old Man Crocodile on Cape York Peninsula Jinki Trevillian Introduction Here I address two subjects that speak to an experience of place that is richly dialogical: our relationships with ghosts and a meeting with a character called Old Man Crocodile, whoÐlike ghosts and spiritsÐinhabits place, but who is both `here' and `not-here', `seen' and `not-seen'. Most of the material focuses on the Edward and Holroyd River regions of the Pormpuraaw community at the south-west base of the Cape York Peninsula, though my discussion draws on research throughout the Peninsula region. My project to collect oral histories from elderly residents of Cape York Peninsula was a deliberate attempt to engage with the history of people through their own stories, and to supplement and challenge the written record. This process of engagement, through field research on the Cape in 1999 and 2000, involved a deep inter-personal exchange and the people themselves, the land itself, and the stories they have told me have not only informed me but affected me profoundly. Ghosts and supernatural beings have been excluded from modern western history as causes because they cannot be `known'. Forces that are `unknown' nonetheless act upon us and within us. This work is engaged with what Dipesh Chakrabarty (2000) describes as translating life-worlds, what Richard Rorty (1989) and Homi Bhabha (1998) call bringing newness into the world; I focus on images, chase metaphors, respond to language and look for ways to relate the stories I was told to other stories so that I might understand them better. -

Great Southern Land: the Maritime Exploration of Terra Australis

GREAT SOUTHERN The Maritime Exploration of Terra Australis LAND Michael Pearson the australian government department of the environment and heritage, 2005 On the cover photo: Port Campbell, Vic. map: detail, Chart of Tasman’s photograph by John Baker discoveries in Tasmania. Department of the Environment From ‘Original Chart of the and Heritage Discovery of Tasmania’ by Isaac Gilsemans, Plate 97, volume 4, The anchors are from the from ‘Monumenta cartographica: Reproductions of unique and wreck of the ‘Marie Gabrielle’, rare maps, plans and views in a French built three-masted the actual size of the originals: barque of 250 tons built in accompanied by cartographical Nantes in 1864. She was monographs edited by Frederick driven ashore during a Casper Wieder, published y gale, on Wreck Beach near Martinus Nijhoff, the Hague, Moonlight Head on the 1925-1933. Victorian Coast at 1.00 am on National Library of Australia the morning of 25 November 1869, while carrying a cargo of tea from Foochow in China to Melbourne. © Commonwealth of Australia 2005 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth, available from the Department of the Environment and Heritage. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Assistant Secretary Heritage Assessment Branch Department of the Environment and Heritage GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601 The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for the Environment and Heritage. -

Author Title Hasluck Paul Workshop of Security. 2/14Th QMI Memorial Service: the Battle of Eland River. Australians in the Boer

Author Title Hasluck Paul Workshop of Security. Memorial Service: The Battle of Eland River. 2/14th QMI Australians in the Boer War. A History of the 2/17 Australian Infantry 2/17 Battalion Committee Battalion, 1940 - 1945. "What We Have We Hold". A History of the 2/17 Australian Infantry 2/17 Battalion Committee Battalion, 1940 - 1945. "What We Have We Hold". Abbot Willis J. The Nations at War Abbott C.L.A. Australia's Frontier Province. The Missiles of October. The story of the Cuban Abel E. missile crisis. Abernethy J A Lot of Fun in My Life. Surgeon's Journey. The autobiography of J. Abraham J.J. Johnston Abraham. Abraham Tom The Cage. A Year in Vietnam. Abrahams P. Jamaica An Island Mosaic. Military Professionalization and Politiical Power. Abrahamsson Bengt (1972) Abshagen K. H. Canaris. Abu H. Tales of a Revolution. Accoce P. & Quat P. The Lucy Ring. Present at the Creation. My years in the State Acheson D. Department. Acheson O. Sketches From Life. Of men I have known. Ackland J. & Word from John. An Australian soldier's letters Ackland R. eds from his friends. Ackroyd J.I. Japan Today. The Great Delusion. A study of aircraft in peace Acworth B. 'neon' and war. A Life of John Hampden. The patriot, 1594 - Adair J. 1643. Adair Lawrens Glass Houses, Paper Men. Adair Lawrens Glass Houses, Paper Men. Adam Smith P. Prisoners of War. World War 2 Time-Life Books, v33, Italy at Adams Henry. War.. The South Wales Borderers (The 24th Adams J. Regiment of Foot). Adams M. -

Hunting Magic, Maintenance Ceremonies and Increase Sites Exploring Traditional Management Systems for Marine Resources in Northern Cape York Peninsula

56174_Extreme_heritage_Part 2_Historical Environment 14/09/11 8:38 AM Page 19 Hunting Magic, Maintenance Ceremonies and Increase Sites Exploring Traditional Management Systems for Marine Resources in Northern Cape York Peninsula. Susan McIntyre-Tamwoy Abstract Introduction Emerging archaeological evidence from archaeological sites in This paper explores the current situation regarding indigenous northern Cape York has the potential to shed light on use of marine turtles in northern Cape York and uses indigenous cultural practices relating to turtle hunting. This archaeological and historical/ethnographic information to paper explores the nexus between cultural practice and identify changes in this ‘indigenous system’ in recent times. In indigenous ecological knowledge and ‘lost’ knowledge which doing this I stress that this is a ‘work in progress’ and it is has implications for how Traditional Owners may chose to expected that on-going research will continue to illuminate this manage resources today. Often when we hear of Indigenous issue. Ongoing research in Northern Cape York (Greer et al. environmental management techniques the focus is on 2005; Greer et al 2011 submitted) is looking more broadly at management ‘practices’ e.g mosaic burning, rather than change and influence in this border between mainland Australia ‘systems’. While not denying that some practices may be and the Torres Strait Islands. This paper focuses on evidence useful or cost effective alternatives to other ‘western science’ from some sites in Northern Cape York -

Seagrass-Watch Proceedings of a Workshop for Monitoring Seagrass Habitats in Cape York Peninsula, Queensland

Seagrass-Watch Proceedings of a Workshop for Monitoring Seagrass Habitats in Cape York Peninsula, Queensland Northern Fisheries Centre, Cairns, Queensland 9th – 10th March 2009 & River of Gold Motel Function Room, cnr Hope & Walker Streets Cooktown, Queensland 26th – 27th March 2009 Len McKenzie & Rudi Yoshida Seagrass-Watch HQ Department of Primary Industries & Fisheries, Queensland First Published 2009 ©Seagrass-Watch HQ, 2009 Copyright protects this publication. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Disclaimer Information contained in this publication is provided as general advice only. For application to specific circumstances, professional advice should be sought. Seagrass-Watch HQ has taken all reasonable steps to ensure the information contained in this publication is accurate at the time of the survey. Readers should ensure that they make appropriate enquires to determine whether new information is available on the particular subject matter. The correct citation of this document is McKenzie, LJ & Yoshida, R.L. (2009). Seagrass-Watch: Proceedings of a Workshop for Monitoring Seagrass Habitats in Cape York Peninsula, Queensland, Cairns & Cooktown, 9-10 and 26–27 March 2009. (Seagrass-Watch HQ, Cairns). 56pp. Produced by Seagrass-Watch -

Boigu Island (Wilson 2005; Schaffer 2010)

PROFILE FOR MANAGEMENT OF THE HABITATS AND RELATED ECOLOGICAL AND CULTURAL RESOURCE VALUES OF MER ISLAND January 2013 Prepared by 3D Environmental for Torres Strait Regional Authority Land & Sea Management Unit Cover image: 3D Environmental (2013) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Mer (Murray) Island is located in the eastern Torres Strait. It occupies a total area of 406 ha, and is formed on a volcanic vent which rises to height of 210m. The stark vent which dominates the island landscape is known as ‘Gelam’, the creator of the dugong in Torres Strait Island mythology. The volcanic vent of Mer is unique in an Australian context, being the only known example of a volcanic vent forming a discrete island within Australian territory. The vegetation on Mer is controlled largely by variations in soil structure and fertility. The western side of the island, which is formed on extremely porous volcanic scoria or ash, is covered in grassland due to extreme soil drainage on the volcano rim. The eastern side, which supports more luxuriant rainforest vegetation and garden areas, occupies much more fertile and favourably drained basaltic soil. A total of six natural vegetation communities, within five broad vegetation groups and two regional ecosystems are recognised on the island, representing approximately 2% of regional ecosystems recorded across the broader Torres Strait Island landscape. The ecosystems recorded are however unique to the Eastern Island Group, in particular Mer and Erub, and have no representation elsewhere in Queensland. There are also a number of highly significant culturally influenced forest types on the island which provide a window into the islands past traditional agricultural practices. -

ABORIGINAL HISTORY 1981 5:1 Matty Young Old Lockhart River

ABORIGINAL HISTORY 1981 5:1 George Rocky Johnson Butcher Matty Young Old Lockhart River lugger-hands who had lengthy associations with Japanese boat-masters. Photographs by Athol Chase 6 ALL KIND OF NATION’: ABORIGINES AND ASIANS IN CAPE YORK PENINSULA* Athol Chase Apart from some interaction with Torres Strait Islanders, the Aborigines of Cape York Peninsula, Queensland, were free from overseas contact until European ‘discovery’ and subsequent settlement occurred in the nineteenth century. Shortly after Europeans arrived, Asians appeared in the Peninsula and its waters, attracted by news of its mineral and marine resources. Their intention, like that of ‘Macassan’ visitors to other north Australian shores in earlier days, was only to exploit the rich natural resources for as long as this was profitable. In Cape York the Asians (particularly the Japanese and Chinese) came to work the mineral fields or to supply the fast-growing lugger industries with specialised labour. Despite European anxiety at the time, these Asians were resource raiders rather than colonists intending to settle the north. There were two main areas of Asian impact in northern Cape York: the rich coastal waters of the Great Barrier Reef where pearlshell and trepang could be found in abundance, and the hills and valleys of the eastern mountain spine where gold and other minerals awaited the fossicker's dish. As a result early contact between Asians and Aborigines was concentrated along the eastern margin of the Peninsula, in particular the coastal strip from Cape York itself to Princess Charlotte Bay. Here the crews of fishing luggers could find well- watered bases in the many bays and river mouths, well out of reach of officialdom.