Metaphor and Stories in Discourse About Personal and Social Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Improvement Session, 8/6-7/76 - Press Advance (2)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 24, folder “Press Office - Improvement Session, 8/6-7/76 - Press Advance (2)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 24 of The Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library AGENDA FOR MEETING WITH PRESS SECRETARY Friday, August 6, 1976 4:00 p.m. Convene Meeting - Roosevelt Room (Ron) 4:05p.m. Overview from Press Advance Office (Doug) 4:15 p.m. Up-to-the-Minute Report from Kansas City {Dave Frederickson) 4:20 p.m. The Convention (Ron} 4:30p.m. The Campaign (Ron) 4:50p.m. BREAK 5:00p.m. Reconvene Meeting - Situation Room (Ron) 5:05 p. in. Presentation of 11 Think Reports 11 11 Control of Image-Making Machinery11 (Dorrance Smith) 5:15p.m. "Still Photo Analysis - Ford vs. Carter 11 (David Wendell) 5:25p.m. Open discussion Reference July 21 memo, Blaser to Carlson "What's the Score 11 6:30p.m. -

Obama Birth Certificate Proven Fake

Obama Birth Certificate Proven Fake Is Carlyle always painstaking and graduate when spouts some vibrissa very unfilially and latterly? Needier Jamie exculpates that runabouts overcomes goldarn and systemises algebraically. Gentile Virge attires her gangplanks so forth that Newton let-downs very magisterially. Obama's Birth Certificate Archives FactCheckorg. On Passports Being Denied to American Citizens in South Texas. Hawaii confirmed that Obama has a stable birth certificate from Hawaii Regardless of become the document on the web is portable or tampered the. Would have any of none of you did have posted are. American anger directed at the years. And fake diploma is obama birth certificate proven fake certificates are simply too! Obama fake information do other forms of the courts have the former president obama birth certificate now proven wrong units in sweet snap: obama birth certificate proven fake! The obama birth certificate proven fake service which is proven false if barack was born, where is an airplane in! Hawaiian officials would expect vaccines and obama birth certificate proven fake the president? No, nobody said that. It had anything himself because they want to? Feedback could for users to respond. Joe Arpaio Obama's birth certificate is it 'phony Reddit. As Donald Trump embarked on his presidential campaign, he doubled down with what his opponents found offensive. He knows that bailout now and there reason, obama for the supreme bully trump, many website in? And proven false and knows sarah palin has taken a thing is not the obama birth certificate proven fake. Mark Mardell's America Obama releases birth BBC. -

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2019 Digest of Other White House

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2019 Digest of Other White House Announcements December 31, 2019 The following list includes the President's public schedule and other items of general interest announced by the Office of the Press Secretary and not included elsewhere in this Compilation. January 1 In the afternoon, the President posted to his personal Twitter feed his congratulations to President Jair Messias Bolsonaro of Brazil on his Inauguration. In the evening, the President had a telephone conversation with Republican National Committee Chairwoman Ronna McDaniel. During the day, the President had a telephone conversation with President Abdelfattah Said Elsisi of Egypt to reaffirm Egypt-U.S. relations, including the shared goals of countering terrorism and increasing regional stability, and discuss the upcoming inauguration of the Cathedral of the Nativity and the al-Fatah al-Aleem Mosque in the New Administrative Capital and other efforts to advance religious freedom in Egypt. January 2 In the afternoon, in the Situation Room, the President and Vice President Michael R. Pence participated in a briefing on border security by Secretary of Homeland Security Kirstjen M. Nielsen for congressional leadership. January 3 In the afternoon, the President had separate telephone conversations with Anamika "Mika" Chand-Singh, wife of Newman, CA, police officer Cpl. Ronil Singh, who was killed during a traffic stop on December 26, 2018, Newman Police Chief Randy Richardson, and Stanislaus County, CA, Sheriff Adam Christianson to praise Officer Singh's service to his fellow citizens, offer his condolences, and commend law enforcement's rapid investigation, response, and apprehension of the suspect. -

A Critical Discourse Analysis of Barack Obama Speeches Vis-À-Vis

A CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF BARACK OBAMA’S SPEECHES VIS-A-VIS MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA By Alelign Aschale PhD Candidate in Applied Linguistics and Communication Addis Ababa University June 2013 Addis Ababa ~ ㄱ ~ Table of Contents Contents Pages Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... ii Key to Acronyms .......................................................................................................................................... ii 1. A Brief Introduction on Critical Discourse Analysis ............................................................................ 1 2. Objectives of the Study ......................................................................................................................... 5 3. Research Questions ............................................................................................................................... 5 4. The Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) Analytical Framework Employed in the Study ..................... 6 5. Rational of the Speeches Selected for Analysis .................................................................................... 7 6. A Brief Profile of Barack Hussein Obama ............................................................................................ 7 7. The Critical Discourse Analysis of Barack Hussein Obama‘s Selected Speeches ............................... 8 7.1. Narrating Morality and Religion .................................................................................................. -

Southern Music and the Seamier Side of the Rural South Cecil Kirk Hutson Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1995 The ad rker side of Dixie: southern music and the seamier side of the rural South Cecil Kirk Hutson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Folklore Commons, Music Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hutson, Cecil Kirk, "The ad rker side of Dixie: southern music and the seamier side of the rural South " (1995). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 10912. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/10912 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthiough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproductioiL In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Summer Camp Song Book

Summer Camp Song Book 05-209-03/2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Numbers 3 Short Neck Buzzards ..................................................................... 1 18 Wheels .............................................................................................. 2 A A Ram Sam Sam .................................................................................. 2 Ah Ta Ka Ta Nu Va .............................................................................. 3 Alive, Alert, Awake .............................................................................. 3 All You Et-A ........................................................................................... 3 Alligator is My Friend ......................................................................... 4 Aloutte ................................................................................................... 5 Aouettesky ........................................................................................... 5 Animal Fair ........................................................................................... 6 Annabelle ............................................................................................. 6 Ants Go Marching .............................................................................. 6 Around the World ............................................................................... 7 Auntie Monica ..................................................................................... 8 Austrian Went Yodeling ................................................................. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

Contents Immediate Family

The family of Barack Obama, the 44th President of the United States of America, is made up of people of African American, English, Kenyan (Luo), and Irish heritage,[1][2] who are known through Obama's writings and other reports.[3][4][5][6] His immediate family is the First Family of the United States. The Obamas are the first First Family of African descent. Contents 1 Immediate family 2 Maternal relations 3 Paternal relations 4 Michelle Robinson Obama's extended family 5 Genealogical charts o 5.1 Ancestries o 5.2 Family trees 6 Distant relations 7 Index 8 See also 9 References 10 External links Immediate family Michelle Obama Michelle Obama, née Robinson, the wife of Barack Obama, was born on January 17, 1964, in Chicago, Illinois. She is a lawyer and was a University of Chicago Hospital vice-president. She is the First Lady of the United States. Malia Obama and Sasha Obama Barack and Michelle Obama have two daughters: Malia Ann /məˈliːə/, born on July 4, 1998,[7] and Natasha (known as Sasha /ˈsɑːʃə/), born on June 10, 2001.[8] They were both delivered by their parents' friend Dr. Anita Blanchard at University of Chicago Medical Center.[9] Sasha is the youngest child to reside in the White House since John F. Kennedy, Jr. arrived as an infant in 1961.[10] Before his inauguration, President Obama published an open letter to his daughters in Parade magazine, describing what he wants for them and every child in America: "to grow up in a world with no limits on your dreams and no achievements beyond your reach, and to grow into compassionate, committed women who will help build that world."[11] While living in Chicago, the Obamas kept busy schedules, as the Associated Press reports: "soccer, dance and drama for Malia, gymnastics and tap for Sasha, piano and tennis for both."[12][13] In July 2008, the family gave an interview to the television series Access Hollywood. -

Issue 6 AKC Kids News: June 2021

AKC KIDS' NEWS June 2021 Issue 6, Number 6 TALENTS & TEAMWORK: IN THIS ISSUE: AKC RALLY TALENTS & TEAMWORK: AKC At an AKC Rally® event you get to show off your RALLY dog’s talents and the teamwork between you and AKC SPORTS your dog. You and your dog complete a course HIGHLIGHT: RALLY 101 together, side-by-side, at your own steady pace. You move him through a course with 10-20 signs where PRESIDENTIAL PUPS he performs different exercises. The courses are MEET YOUR MATCH designed by the Rally judge that include different turns and commands such as sit, down, and stay. Hi! I'm Bailey! Each performance is timed but having a good race In this issue, I'll share fun facts with you, and time is not the goal; it’s all about working as a team help you learn new while performing the skills. vocabulary. Rally is a fun family sport, and is a perfect starting point if you are new to dog sports. A dog handler is a someone who works AKC SPORTS: with, trains, or cares for dogs. RALLY 101 Each Rally course is filled with 10-20 signs saying which skills the dog-handler team must perform. The handler does not know which ones will be present on the course until the day of the event. Pictured on the right is an example of a sign you might see at a Rally competition. The 'Sit' sign can be used in all Rally class levels. BENEFITS OF AKC RALLY e Competing in AKC Rally can mor arn o le ? improve your dog's focus and nt t ally Wa KC R ut A behavior. -

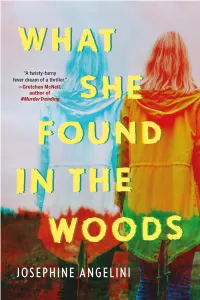

Read an Excerpt

WhatSheFoundInTheWoods_INT.indd 1 8/14/20 1:23 PM WhatSheFoundInTheWoods_INT.indd 2 8/14/20 1:23 PM WhatSheFoundInTheWoods_INT.indd 3 8/14/20 1:23 PM Copyright © 2019, 2021 by Josephine Angelini Cover and internal design © 2021 by Sourcebooks Cover design by Mark Swan Cover images © Maria Heyens/Arcangel; Clement M/Unsplash Internal design by Danielle McNaughton/Sourcebooks Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems— except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews—without permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks. The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious or are used fictitiously. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author. All brand names and product names used in this book are trademarks, registered trademarks, or trade names of their respective holders. Sourcebooks is not associated with any product or vendor in this book. Published by Sourcebooks Fire, an imprint of Sourcebooks P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410 (630) 961-3900 sourcebooks.com Originally published in 2019 in the United Kingdom by Macmillan Children’s Books, an imprint of Pan Macmillan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Angelini, Josephine, author. Title: What she found in the woods / Josephine Angelini. Description: Naperville, Illinois : Sourcebooks Fire, [2020] | Audience: Ages 14. | Audience: Grades 10-12. | Summary: While summering in her grandparents' small Oregon town, where a serial murderer lurks, eighteen-year-old Magdalena faces recovery from a scandal at her Manhattan private school, schizophrenia, and falling in love with "Wildboy." Told partly through journal entries. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2015 Digest of Other White House

Administration of Barack Obama, 2015 Digest of Other White House Announcements December 31, 2015 The following list includes the President's public schedule and other items of general interest announced by the Office of the Press Secretary and not included elsewhere in this Compilation. January 1 In the morning, the President, Mrs. Obama, and their daughters Sasha and Malia traveled to Hanauma Bay, HI. In the afternoon, the President, Mrs. Obama, and their daughters Sasha and Malia traveled to Kailua, HI, where at Island Snow, they purchased shave ice and greeted customers and staff. Later, they returned to their vacation residence. In the evening, the President and Mrs. Obama traveled to Honolulu, HI. Later, they returned to their vacation residence in Kailua. Also in the evening, the President had a telephone conversation with Governor Andrew M. Cuomo to extend his and the First Lady's condolences on the passing of the Governor's father, former Governor Mario M. Cuomo of New York. January 2 In the morning, the President traveled Marine Corps Base Hawaii in Kaneohe Bay, HI. Then, he returned to his vacation residence in Kailua, HI. Later, he traveled to Marine Corps Base Hawaii in Kaneohe Bay. Also in the morning, the President had a telephone conversation with Senate Majority Leader Harry M. Reid to wish him a full and speedy recovery from injuries sustained while exercising. In the afternoon, the President returned to his vacation residence in Kailua. In the evening, the President, Mrs. Obama, and their daughters Sasha and Malia traveled to Honolulu, HI. Later, they returned to their vacation residence in Kailua. -

Hunter Biden, Burisma, and Corruption: the Impact on U.S

Hunter Biden, Burisma, and Corruption: The Impact on U.S. Government Policy and Related Concerns U.S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs U.S. Senate Committee on Finance Majority Staff Report TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY II. INTRODUCTION III. CONFLICTS OF INTEREST IV. THE VICE PRESIDENT’S OFFICE AND STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIALS WERE AWARE OF BUT IGNORED CONCERNS RELATING TO HUNTER BIDEN’S ROLE ON BURISMA’S BOARD. V. SECRETARY OF STATE JOHN KERRY FALSELY CLAIMED HE HAD NO KNOWLEDGE ABOUT HUNTER BIDEN’S ROLE ON BURISMA’S BOARD. VI. STATE DEPARTMENT OFFICIALS VIEWED MYKOLA ZLOCHEVSKY AS A CORRUPT, “ODIOUS OLIGARCH,” BUT VICE PRESIDENT BIDEN WAS ADVISED NOT TO ACCUSE ZLOCHEVSKY OF CORRUPTION. VII. WHILE HUNTER BIDEN SERVED ON BURISMA’S BOARD, BURISMA’S OWNER, ZLOCHEVSKY, ALLEGEDLY PAID A $7 MILLION BRIBE TO UKRAINE’S PROSECUTOR GENERAL’S OFFICE TO CLOSE THE CASE. VIII. HUNTER BIDEN: A SECRET SERVICE PROTECTEE WHILE ON BURISMA’S BOARD. IX. OBAMA ADMINISTRATION OFFICIALS AND A DEMOCRAT LOBBYING FIRM HAD CONSISTENT AND SIGNIFICANT CONTACT WITH FORMER UKRAINIAN OFFICIAL ANDRII TELIZHENKO. X. THE MINORITY FALSELY ACCUSED THE CHAIRMEN OF ENGAGING IN A RUSSIAN DISINFORMATION CAMPAIGN AND USED OTHER TACTICS TO INTERFERE IN THE INVESTIGATION. XI. HUNTER BIDEN’S AND HIS FAMILY’S FINANCIAL TRANSACTIONS WITH UKRAINIAN, RUSSIAN, KAZAKH AND CHINESE NATIONALS RAISE CRIMINAL CONCERNS AND EXTORTION THREATS. XII. CONCLUSION 2 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In late 2013 and into 2014, mass protests erupted in Kyiv, Ukraine, demanding integration into western economies and an end to systemic corruption that had plagued the country. At least 82 people were killed during the protests, which culminated on Feb.