“Is Oliver Dreaming?” Revisited: the Mystery of Oliver Twist* Tomoya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles Dickens' Corruption and Idealization Personified in Oliver Twist

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Academic Excellence Showcase Proceedings Student Scholarship 2018-06-02 Charles Dickens’ Corruption and Idealization Personified in Oliver Twist Ellie Phillips Western Oregon University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/aes Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Phillips, Ellie, "Charles Dickens’ Corruption and Idealization Personified in Oliver Twist" (2018). Academic Excellence Showcase Proceedings. 150. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/aes/150 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Academic Excellence Showcase Proceedings by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Byrd 1 Ellie Byrd Dr. Lange ENG 218w Charles Dickens’ Corruption and Idealization Personified in Oliver Twist In Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist, the depictions of corruption and virtue are prevalent throughout most of the novel and take the physical form in the city and the country. Oliver spends much of his time in London among criminals and the impoverished, and here is where Dickens takes the city of London and turns it into a dark and degraded place. Dickens’ London is inherently immoral and serves as a center for the corruption of mind and spirit which is demonstrated through the seedy scenes Dickens paints of London, the people who reside there, and by casting doubt in individuals who otherwise possess a decent moral compass. Furthermore, Dickens’ strict contrast of the country to these scenes further establishes the sinister presence of London. -

Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens

School Radio Oliver Twist By Charles Dickens EPISODE SIX NARRATOR: Oliver’s ailings were neither slight nor few; but, at length, he began to get better and to be able to say sometimes - in a few tearful words - how deeply he felt the goodness of the two sweet ladies and how ardently he hoped that, when he grew strong and well again, he could do something to show his grati- tude. He was anxious too to find Mr Brownlow and to give his account of what had happen on the day he had been entrusted with the errand to the book-seller. Dr Losberne took Oliver to London, but the house was empty - a neighbour’s servant informing them that Mr Brownlow had gone to the sold West Indies some six weeks before. This bitter disappointment caused Oliver much sorrow, even in the midst of his happiness. Then after another fortnight, when the spring weather had fairly begun, preparations were made for leaving Chertsey for a few months in a cottage in the country. It was a happy time and every morning Oliver went to a white-headed old gentleman, who lived nearby, who taught him to read better and to write... TUTOR Well, Oliver, this has always been one of my favourite books and I’m inclined to think you’ll like it too... NARRATOR In the evenings, Rose would sit down to the piano and play some pleasant tune, or sing some old song which it pleased her aunt to hear. So spring flew swiftly by. But then, came a heavy blow. -

Fiction Excerpt: from Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens

Fiction Excerpt: From Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens Oliver Twist was the second novel written by Charles Dickens. It was first published as a serial, with new chapters printed monthly in the magazine Bentley’s Miscellany over the course of two years (1837–1839). The novel tells the story of an orphan named Oliver Twist, who was born in a workhouse and later escaped to join a gang of thieves. This excerpt takes place during Oliver’s time in the workhouse. The room in which the boys were fed, was a large stone hall, with a copper [a large, heated copper pot] at one end: out of which the master, dressed in an apron for the purpose, and assisted by one or two women, ladled the gruel [a watery cereal like very thin oatmeal] at mealtimes. Of this festive composition each boy had one porringer [small bowl], and no more—except on occasions of great public rejoicing, when he had two ounces and a quarter of bread besides. The bowls never wanted washing. The boys polished them with their spoons till they shone again; and when they had performed this operation (which never took very long, the spoons being nearly as large as the bowls), they would sit staring at the copper, with such eager eyes, as if they could have devoured the very bricks of which it was composed; employing themselves, meanwhile, in sucking their fingers most assiduously [diligently], with the view of catching up any stray splashes of gruel that might have been cast thereon. Boys have generally excellent appetites. -

Oliver Twist

APPENDIX B Summary of Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist In a parish workhouse, a nameless young woman dies after giving birth. Her son, Oliver Twist—as named by the beadle, Mr. Bumble—is sent to a separate branch of the workhouse with other orphaned infants and raised by the monstrous Mrs. Mann. Oliver miraculously survives the horrors of the “baby farm,” and, on his ninth birthday, is transferred to the central workhouse. After three months of slow starvation, the boys draw lots to see who will ask for more gruel; Oliver draws the long straw and carries out this unenviable task. Bumble and the board of directors severely punish Oliver and plan to turn him out of the workhouse. After a failed attempt to apprentice him to a brutal chimney sweep, Bumble eventually manages to unload Oliver on Mr. Sowerberry, the undertaker. On top of his depressing new trade, Oliver must deal with the bullying of his fel- low apprentice, Noah Claypole. Oliver finally fights back against Noah when his rival taunts him about his deceased mother. This second “rebellion” earns Oliver a stern rebuke from Bumble and a brutal beating from Sowerberry. Consumed by the misery of his life, Oliver decides to run away, though he first returns to the baby farm to bid goodbye to his friend, Dick. Oliver barely survives the seventy-five mile walk to London. On arriving at Barnett, he encounters a strangely attired cockney boy who introduces himself as Jack Dawkins (though he goes by the name of the Artful Dodger). The Dodger invites Oliver to come and lodge with a respectable old gentleman, and he conducts a wary Oliver through the slums of London to a dilapidated flat. -

Stage 1 Teen Readers Characters

CHARLES DICKENS CHARLES Stage 1 Stage Teen ELI Readers Teen A1 Teen Readers Characters Mr Sowerberry Oliver Mrs Sowerberry Doctor Losberne Mr Bumble Monks Dodger Fagin Bill Sikes Nancy Mr Brownlow Mrs Bedwin Rose Maylie Mrs Maylie Charles Dickens Oliver tells Mrs Sowerberry that Noah said horrible things about his mother but she doesn’t listen to him. She throws him in a cold, dark room. She closes the door but she forgets to lock it. Oliver stays in the room for many hours. It is very late and the house is silent. Mr and Mrs Sowerberry are asleep. Oliver doesn’t know what to do. He didn’t like the workhouse and he doesn’t like Mr and Mrs Sowerberry and Noah. Then, he has an idea. He decides to run away*. He slowly opens the door to the room and quietly walks to the kitchen. Then, he opens the kitchen window and jumps out into the street, but he doesn’t know where to go. He can see the church and the baker’s and the butcher’s in the town centre. Then, he sees a big road. He runs down the road, away from the town and Mr Sowerberry’s shop and the workhouse. to run away to leave a place you don’t like 16 Oliver Twist 17 After-reading Activities Grammar 1 Where does Oliver live? Number the boxes. A ■ Mr Brownlow’s townhouse B ■ Rose’s cottage C ■ Fagin’s house D ■1 The workhouse E ■ Mr Brownlow’s cottage F ■ Rose’s townhouse G ■ Mr Sowerberry’s shop 2 Complete Oliver’s family tree. -

And Charles Dickens' Oliver Twist

A OUEY OUG E UEWO I SAI A EGA RINC'ONETE Y CORTADILLO A OIE TWIST EOAI-I IEICK UIESIA E AAOI eoayuaes E Oliver Twist, C ickes se eaya e ua cíica e as coicioes sociaes e a Igaea e sigo I cuya uea aía eeimeao e iño E uuo e Oie u oe uéao se eae ee as gaas e ama y a iáaa ia e a cases acomoaas E Rinconete y Cortadillo, uicao o Migue e Ceaes e 113 ceemos e e uo e aia e a eesa oea e ickes Ese aícuo esuia os uos e coaco ee amas oas o que oiga a ua eeió soe as caaceísicas e géeo y amié ua iagació e a iuecia e Ceaes e a ieaua igesa Caes ickes ook i uo imse o ciicie e socia coiios i 19 ceuy Ega o wic e imse as a ci a ee a oeia icim i e soy o Oie wis a youg oa wose uue as a eique o a uig meme o sociey is e suec o eae a iigue Rinconete and Cortadillo, wie wo ceuies eaie y Migue e Ceaes wou seem o e a saig oi o ickes Oliver Twist as umeous ois o coac ca e ieiie is eas o e quesio o e caaceisics o gee as we as e iuece o Ceaes o Egis ieaue A cose eaig o Migue e Ceaes Rinconete y Cortadillo (113 a Caes ickes Oliver Twist (137-139 igs o ig a seies o eemes wic wou o seem o oey o mee coiciece Ee gie e ieeces ewee Goe Age Seiia sociey a eay 19á ceuy oo a commo ea aiuae o Exemplaria 6, 1-9 ISS 113-19 © Uiesia e uea Universidad de Huelva 2009 82 EOA IEICK sae iogaica eeieces a a commo ouook o ie ueies o woks o is mus e ae o e eouio o e icaesque oe a e ieay aiio o Ceaes a is woks i Ega o oy wi eeece o ickes imse u aso o e iis wies wo iuece im Seie i e 1h a 17h ceuies was a meig o a aace eoe om may couies a a waks o ie Ayoe esiig o emak o Sais ew Wo eioies was -

Hunger for Life in Oliver Twist Novel

www.ijcrt.org © 2018 IJCRT | Volume 6, Issue 4 October 2018 | ISSN: 2320-2882 HUNGER FOR LIFE IN OLIVER TWIST NOVEL Karabasappa Channappa Nandihally Assistant Professor Of English Government First Grade College, U.G.&P.G.Centre Dental College Road,Vidyanagar,Davanagere. Abstract This novel focusing on Poverty is a prominent concern in Oliver Twist. Throughout the novel, Dickens enlarged on this theme, describing slums so decrepit that whole rows of houses are on the point of ruin. In an early chapter, Oliver attends a pauper's funeral with Mr. Sowerberry and sees a whole family crowded together in one miserable room.This prevalent misery makes Oliver's encounters with charity and love more poignant. Oliver owes his life several times over to kindness both large and small.[14] The apparent plague of poverty that Dickens describes also conveyed to his middle-class readers how much of the London population was stricken with poverty and disease. Nonetheless, in Oliver Twist, he delivers a somewhat mixed message about social caste and social injustice. Oliver's illegitimate workhouse origins place him at the nadir of society; as an orphan without friends, he is routinely despised. His "sturdy spirit" keeps him alive despite the torment he must endure. Most of his associates, however, deserve their place among society's dregs and seem very much at home in the depths. Noah Claypole, a charity boy like Oliver, is idle, stupid, and cowardly; Sikes is a thug; Fagin lives by corrupting children, and the Artful Dodger seems born for a life of crime. Many of the middle-class people Oliver encounters—Mrs. -

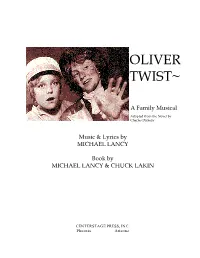

Oliver Twist~

OLIVER TWIST~ A Family Musical Adapted from the Novel by Charles Dickens Music & Lyrics by MICHAEL LANCY Book by MICHAEL LANCY & CHUCK LAKIN CENTERSTAGE PRESS, INC. Phoenix Arizona OLIVER TWIST Copyright 1976 by Michael Lancy Copyright 1981 by Michael Lancy & Chuck Lakin Printed in U.S.A. ISBN: 1-890298-27-1 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Warning: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that OLIVER TWIST is subject to royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, the British Empire, including the Dominion of Canada, and all other countries of the Copyright Union. All rights, including professional, amateur, motion pictures, recita- tion, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, and the rights of transla- tion into foreign languages are strictly reserved. For all rights apply to CENTERSTAGE PRESS, www.centerstagepress.com, (602) 242-1123. Copying from this script, in whole or in part, by any means is strictly forbidden by law and the right of performance is not transferable. Particular emphasis is laid on the ques- tion of amateur or professional readings, permission and terms for which must be secur- ed in written form from Centerstage Press, Inc. Whenever this play is produced the following notice must appear on all programs, printing and advertising for the play: “Produced by special arrangement with Centerstage Press.” Due authorship credit must be given on all programs, printing and advertising for the play. NO CHANGES SHALL BE MADE IN THE PLAY FOR THE PURPOSE OF YOUR PRODUCTION UNLESS AUTHORIZED IN WRITING. ~ CHARACTERS ~ MR. BUMBLE: A portly man of middle age, Bumble fancies himself a man of some great importance and distinction. -

Oliver Twist

Oliver Twist Plot Overview Oliver Twist is born in a workhouse in 1830s England. His mother, whose name no one knows, is found on the street and dies just after Oliver’s birth. Oliver spends the first nine years of his life in a badly run home for young orphans and then is transferred to a workhouse for adults. After the other boys bully Oliver into asking for more gruel at the end of a meal, Mr. Bumble, the parish beadle, offers five pounds to anyone who will take the boy away from the workhouse. Oliver narrowly escapes being apprenticed to a brutish chimney sweep and is eventually apprenticed to a local undertaker, Mr. Sowerberry. When the undertaker’s other apprentice, Noah Claypole, makes disparaging comments about Oliver’s mother, Oliver attacks him and incurs the Sowerberrys’ wrath. Desperate, Oliver runs away at dawn and travels toward London. Outside London, Oliver, starved and exhausted, meets Jack Dawkins, a boy his own age. Jack offers him shelter in the London house of his benefactor, Fagin. It turns out that Fagin is a career criminal who trains orphan boys to pick pockets for him. After a few days of training, Oliver is sent on a pickpocketing mission with two other boys. When he sees them swipe a handkerchief from an elderly gentleman, Oliver is horrified and runs off. He is caught but narrowly escapes being convicted of the theft. Mr. Brownlow, the man whose handkerchief was stolen, takes the feverish Oliver to his home and nurses him back to health. Mr. Brownlow is struck by Oliver’s resemblance to a portrait of a young woman that hangs in his house. -

Oliver Twist Co-Planning: Fagin T14/F16

Oliver Twist Co-planning: Fagin T14/F16 Subject knowledge development Mastery Content for Fagin lesson Review this mastery content with your teachers. Be aware that the traditional and foundation pathways are very different for this lesson. Foundation Traditional • Oliver wakes up and notices Fagin looking at his jewels and Fagin snaps at him in a threatening way. • The meaning of the word villain • Fagin is a corrupt villain • Fagin is selfish. • Fagin teaches Oliver a new game: how to pick pockets. • Oliver doesn’t realise Fagin is a villain • Fagin is a villain because he tricks Oliver into learning how to • Fagin is a corrupt villain steal. • Nancy and Bet arrive and Oliver thinks Nancy is beautiful. Start at the end. Briefly look through the lesson materials for this lesson in your pathway, focusing in particular on the final task before the MCQ: what will be the format of this final task before the MCQ with your class? Get teachers to decide what they want the final task before the MCQ to look like in their classroom. What format will it take? It would be good to split teachers into traditional and foundation pathway teachers at this point. Below is a list of possible options that you could use to steer your teachers: • Students write an analytical paragraph about Fagin as a villain (traditional) • Students write a bullet point list of what evidence suggests Fagin is a villain (traditional) • Students write a paragraph about how Fagin is presented in chapter 10 (foundation). • Students explode a quotation from chapter 10 explaining how Fagin is presented. -

Oliver!? Sharon Jenkins: Working Together

A Study Guide for... BOOK, MUSIC & LYRICS BY LIONEL BART Prepared by Zia Affronti Morter, Molly Greene, and the Education Department Staff. Translation by Carisa Anik Platt Trinity Rep’s Education Programs are supported by: Bank of America Charitable Foundation, The Murray Family Charitable Foundation, The Yawkey Foundation, Otto H. York Foundation, The Amgen Foundation, McAdams Charitable Foundation, Rhode Island State Council on the Arts, The Hearst Foundation, Haffenreffer Family Fund, Phyllis Kimball Johnstone & H. Earl Kimball Foundation, Target FEBRUARY 20 – MARCH 30, 2014 trinity repertory company PROVIDENCE • RHODE ISLAND TABLE OF CONTENTS Theater Audience Etiquette 2 Using the Guide in Your Classroom 3 Unit One: Background Information 4-11 A Conversation with the Directors: Richard and Sharon Jenkins 4 A Biography of Charles Dickens 5 Oliver’s London 6 The Plot Synopsis 8 The Characters 9 Important Themes 10 Unit 2: Entering the Text 12-21 Make Your Own Adaptations 12 Social Consciousness & Change 13 Inequitable Distribution of Resources 14 Song Lyrics Exercise 15 Scenes from the Play 17 Further Reading & Watching 21 Bibliography 23 THEATER AUDIENCE ETIQUETTE AND DISCUSSION PLEASE READ CAREFULLY AND GO OVER WITH YOUR CLASSES BEFORE THE SHOW TEACHERS: Speaking to your students about theater etiquette is ESSENTIAL. Students should be aware that this is a live performance and that they should not talk during the show. If you do nothing else to prepare your students to see the play, please take some time to talk to them about theater etiquette in an effort to help the students better appreciate their experience. It will enhance their enjoyment of the show and allow other audience members to enjoy the experience. -

“The Other Woman” – Eliza Davis and Charles Dickens

44 DICKENS QUARTERLY “The Other Woman” – Eliza Davis and Charles Dickens MURRAY# BAUMGARTEN University of California, Santa Cruz he letters Eliza Davis wrote to Charles Dickens, from 22 June 1863 to 8 February 1867, and after his death to his daughter Mamie on 4 August 1870, reveal the increasing self-confidence of English Jews.1 TIn their careful and accurate comments on the power of Dickens’s work in shaping English culture and popular opinion, and their pointed discussion of the ways in which Fagin reinforces antisemitic English and European Jewish stereotypes, they indicate the concern, as Eliza Davis phrases it, of “a scattered nation” to participate fully in the life of “the land in which we have pitched our tents.2” It is worth noting that by 1858 the fits and starts of Jewish Emancipation in England had led, finally, to the seating of Lionel Rothschild in the House of Commons. After being elected for the fifth time from Westminster he was not required, due to a compromise devised by the Earl of Lucan and Benjamin Disraeli, to take the oath on the New Testament as a Christian.3 1 Research for this paper could not have been completed without the able and sustained help of Frank Gravier, Reference Librarian at the University of California, Santa Cruz, Assistant Librarian Laura McClanathan, Lee David Jaffe, Emeritus Librarian, and the detective work of David Paroissien, editor of Dickens Quarterly. I also want to thank Ainsley Henriques, archivist of the Kingston Jewish Community of Jamaica, Dana Evan Kaplan, the rabbi of the Kingston Jewish community, for their help, and the actress Miryam Margolyes for leading the way into genealogical inquiries.