Beyond Education's Iron Cage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vittoria Booster the Vittoria Booster Newsletter Is Published Twice a Year by the Vittoria & District Foundation for Its Members and Supporters

SOME OF THE STUFF INSIDE Amanda – In the Hall 8-9 Jessie – Turns Pro 6 Relay for Life 21-22 Auction 2011 2, 22-23 Kim – Dr. Marshall Award 10-11 Rob – New Job 9-10 Barbershoppers & Choir 5 Linda – Recruiting Doctors 21 Rural Lifesavers 19 Beverly – Just For You 10 Local Art Wanted 22 Shana – Harbour Museum 11-12 Burning Kiln Winery 24 M&M Charity BBQ 14 St. John’s Anglican 24 Candids & Potpourri 25-28 Norfolk County Tourism 15-18 Tidbits of Trivia 22 Celina – Wins Gold 8 Norfolk W.I. 14 Tom – Lee Brown Committee 11 Cindy – Honolulu Marathon 6-8 Normandale Beach Clutter 20 Turbines at Port Ryerse? 18-19 Fred – At home & On Tour 4-5 Peter – Ukulele 3-4 Virginia – Bridal Showcase 15 French Immersion at Walsh 18 Raising Bell at Port Ryerse 20-21 Volunteer Awards 12-14 NO. 29 – SUMMER 2011 • PUBLISHED AT VITTORIA, ONTARIO (519) 426-0234 The Vittoria Booster The Vittoria Booster Newsletter is published twice a year by The Vittoria & District Foundation for its Members and Supporters. e-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] website: http://www.vittoria.on.ca webmaster’s e-mail: [email protected] A n in front of a person’s name indicates that he or she is a member of The Vittoria & District Foundation Milestone Anniversaries Celebrated Katie and Harry Verbakel - 60th on January 30 In Memoriam nGertrude and nClair Smith - 50th on April 21 Millie and Eric Corbett - 60th on May 5 Muriel and nJohn Dennis - 55th on June 2 nRuth (Sheppard) Gundry - 73 - on January 17 nMarie and nDonald Ames - 55th on June 2 Charles “Moe” Hamm - 79 - on January 23 nPat and nJim Tiller - 50th on June 24 Robert Bruce “Bob” McKenzie - 80 - on January 23 Eunice and Bob Vervaeke - 50th on June 24 Douglas Bethune - 47 nEvelyn and Ernest Shoff - 55th on June 30 Katherine Vermeersch - 51 - on January 30 “John” Leigh Corbett - 79 - on January 30 OTHERS IN THE OVER 60 CLUB “John” William Erford Reece - 79 - on February 2 Gloria and Don Dutton - 61st on May 24 William Paul “Bill” Haskett - 82 - on February 14 Joseph Constant “Guy” Talty - 81 - on February 16 Rev. -

Appendix C – Case Studies and Best Practices

Innovation-Based Economic Development Strategy for Holyoke and the Pioneer Valley Appendix C Case Studies and Best Practices MASSACHUSETTS TECHNOLOGY COLLABORATIVE Innovation-Based Economic Development Strategy for Holyoke and the Pioneer Valley 1. HIGH PERFORMANCE COMPUTING CENTERS Today there are approximately 100-150 high-performance computing centers located across the United States.1 Many of these are located on or near university campuses and the degree of accessibility to these facilities by commercial enterprises is variable. The Massachusetts Green High Performance Computing Center (MGHPCC) in Holyoke would be structured primarily to serve MGHPCC consortium faculty members, but some access will be granted to industry under certain conditions. This arrangement with industry, but focus on academic research, is shared by many of the nation‘s existing supercomputing centers.2 In terms of the impact on the local and regional economy, the smaller HPC facilities typically offer 8-15 jobs. Some of the larger centers, such as those that support Department of Energy or National Science Foundation research, range from 40 to 200 employees.3 The number of employees depends largely on the services the center provides. Many large centers grounded in research will have staff with expertise in: System administration; Operations & account management; Scientific applications expertise; A help line; File systems expertise; Post-processing and visualization; and Code development. These numerous services require a range of expertise and professionals; hence, the staff of these facilities tends to be larger. While some of these services will be required at the GHPCC, it is anticipated that the number of people likely to be employed by the center will fall on the lower end of the range for HPCs in the near term. -

Norfolk County Corporate Strategic Plan 2015-2019

Norfolk County Corporate Strategic Plan 2015 - 2019 FINAL REPORT January 2015 Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction .................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Strategic Planning Process ........................................................................................... 5 2 Corporate Mission, Vision and Key Principles ................................................ 6 2.1 Mission Statement ......................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Vision............................................................................................................................. 6 2.3 Key Principles ............................................................................................................... 7 3 The Context for Change ................................................................................. 8 3.1 Drawing from our Past Strategy .................................................................................... 8 3.2 Planning for the Future ................................................................................................ 10 4 The Community’s Voice ............................................................................... 12 4.1 Engagement Process and Outcomes ......................................................................... 12 5 SWOT Assessment ..................................................................................... -

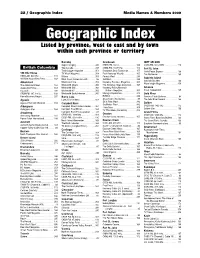

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance. -

Community Hub the School Was Added Later on the Same Site

ISSN 0840-7339 ISBN 978-1-926888-04-0 T H n this third book of our Iron Cage series, we look at the return of the idea E of Community Schools and what it means in practice during the current S TThhee SScchhooooll aass C neo-liberal ascendancy. Policy wonks, corporate think tanks and education H officials can’t seem get enough of them, which gives us good reasons to worry. O But there is also room for some optimism here. The demand for Community O I L CCoommmmuunnity HHub Schools has genuine progressive support provided they stay true to their A purpose. And in the struggle to keep them on course, we get a chance to rethink S C BBeeyyoond Education’ss Iron Cage our schools as democratic institutions, uniting “really useful” learning and O community development. M M These articles explore both sides of the Community School reality in several U N Hugo Aboites Canadian provinces, Mexico, South Africa, the UK and Australia. They give I T examples of schools as genuine two-way community hubs and the thinking Y Chris Bigum behind them. At the same time, they sound alarm bells as the human H U Rita Bouvier dimensions of community development are sidelined in the rush to impose a B business model of corporate development. David Clandfield O U Larry Kuehn Alongside this struggle for community in education, we face widespread R Richard Hatcher closures of neighbourhood schools as part of the continuing financial cutbacks S Richard Hatcher C in public education. The good news – if we can organize around it – is that there H Elise Houghton is now a practical, democratic alternative to closing schools: the school as O community hub. -

Hidenosaunee Inside F. Ìiihi,T,T 1

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA NJtQR NAt6,s Bibliotheque et Archives Canada I I I I I II I, 3 3286 54 ,- _II 1 I r_ - r r .-1 # 1 - r i ` Library and Archives tt . Canada l , Newspaper Collection e . -P'?_ ' T 395 Wellington St. NativE North America's #1 1 ti Ottawa, ON K A ON4 5th oq Pub. No. 40016309 Reg. No. 10963 4t446. .* ti4 Celebrating 15 years - ---r- - Wednesday September 16, \2009 Okarahshona kenh Onkwehonwene, Six Nations of the Grand I - Band council lawsuit hampers talks Dundalk, ON, Canada Hidenosaunee Six Nations band council 7J; lawsuit may force Canada Q s Places To Grow - from negotiation table Plan r By Lynda Powless Editor Six Nations band councils relaunched trust account lawsuit Toronto against Canada may end up shutting down the now three year L ;, ON, Canada a old Six Nations land rights negotiations just as Confederacy a and Ontario are pushing for a mediator to move the talks .0 Mississauga along. - ivn t At the same time Elected Chief nailing a split in the Six Nations r f without joint negotiations that have kept all 7 Bill Montour has also, f" Confederacy consultation, sent a parties at the negotiating table and Waterloo, ON, Canad r letter to Prime Minister Stephen saw the agreement to return the Y c, i, -...15 Harper demanding a tripàrty meet- Burtch property, the first lands to ing between the federal govern- be returned to Six Nations in gen- erations, and resulting federal in- t o ment, Ontario and his band council Hamilton only. -

Solid Waste Future Needs Study

County of Brant Solid Waste Disposal Future Needs Study FINAL STUDY REPORT May 6, 2011 COUNTY OF BRANT SOLID WASTE DISPOSAL FUTURE NEEDS STUDY This page left blank intentionally. COUNTY OF BRANT SOLID WASTE DISPOSAL FUTURE NEEDS STUDY Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................. E1-E11 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ............................................................................. 1 2.0 WASTE DISPOSAL PROJECTIONS.................................................................................. 3 2.1 METHODOLOGY................................................................................................................ 3 2.2 POPULATION GROWTH PROJECTIONS ......................................................................... 3 2.3 PER CAPITA WASTE DISPOSAL RATES......................................................................... 4 2.4 WASTE DISPOSAL PROJECTIONS.................................................................................. 5 3.0 IDENTIFICATION OF ALTERNATIVE DISPOSAL OPTIONS ............................................ 8 3.1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 8 3.2 METHODOLOGY................................................................................................................ 8 3.3 THERMAL TREATMENT TECHNOLOGIES ...................................................................... 9 3.3.1 Introduction ......................................................................................................... -

Norfolk County Economic Development Strategy

Norfolk County Economic Development Strategy Prepared by: November 10, 2011 Adopted by Norfolk County Council December 6, 2011 Recommendations Numbered for Linkage to Monitor Report Norfolk County – Economic Development Strategy Table of Contents The Background ........................................................................................... 1 What the Numbers Say ................................................................................ 2 SWOT Summary: Community Consultation ................................................. 4 What People Value in Norfolk County ......................................................... 8 Guiding Economic Development Principles (Future Directions) ................. 9 Norfolk County’s Economic Development Strategy ................................... 10 Norfolk County – Economic Development Strategy The Background Context Norfolk County, a rural municipality of approximately 68,000 residents in Southwestern Ontario, has long been home to a flourishing agricultural base. Historically, the County’s strength was in tobacco due to the mild climate and long growing season; however, due to the diminishing demand for tobacco products, Norfolk County has encountered a need to diversify not only its agricultural industry, but also its economy. Located along on the shores of Lake Erie, Norfolk County is comprised of several small communities spread across a large geographical area. Some of the communities within the County are Simcoe, Delhi, Port Dover, Waterford, Port Rowan, Langton and Courtland. Norfolk County is Ontario’s Garden - the County is home to some of the most fertile land in Ontario and the agricultural industry continues to be a driving force behind the County’s economy, producing a wide range of crops, including 54% of Ontario’s asparagus, and 58% and 51% of the province’s tobacco and ginseng, respectively. As a result of the County’s agriculture sector’s transformation away from tobacco, farmers have begun growing alternative crops such as lavender, wolfberries, hazelnuts and ginseng. -

The Sustainability Case for Community Power: Empowering Communities Through Renewable Energy

The Sustainability Case for Community Power: Empowering Communities Through Renewable Energy Sarah Martin Date of Submission A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies, York University Ontario, Canada. Student’s Signature Supervisor’s signature __________________________________ ___________________________________ 1 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my loving parents for all their support, not only throughout the MES program, but also throughout the path that has led me here today. Without their strength and belief in my accomplishments, I would not have been able to experience what I have been so lucky to experience to date. They have also provided me invaluable lessons and values that have created my passion for sustainability. Thank you so much to all my friends and peers within the MES program: Brian, Claire, Hazel, Ian, Julia, Justine, Rebecca, Stephanie and Tom. Our endless debates about environmental issues as well as your ongoing advice gave me the support needed during the writing process. Many thanks to my supervisor, Mark Winfield, for guiding me through this process, which at times was overwhelming, and for helping me put the task at hand into perspective. Thank you to Stefan Gsänger, my internship supervisor, who gave me the opportunity to work at the World Wind Energy Association and who helped me understand the importance of Community Power. Thank you to my advisor, Jose Etcheverry, for his endless passion and constant motivation from the very beginning to the very end of my journey in this program. 2 Abstract The purpose of this major research paper is to examine the potential impacts of community ownership models, referred to in this paper as Community Power (CP). -

Situational Analysis Norfolk County Parks, Facilities and Recreation Master Plan

June, 2015 SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS NORFOLK COUNTY PARKS, FACILITIES AND RECREATION MASTER PLAN Submitted by: Cover Page Image Source: www.flickr.com 509-318 Homer St Vancouver BC Canada V6B 2V2 | p: 604.899.3806 | f: 604.899.3805 51 Wolseley Street Toronto ON Canada M5T 1A4| p: 416.645.7033 | f: 416 645 7046 [email protected] | www.elac.ca E. Lees & Associates Consulting Ltd. June, 2015 The Corporation of Norfolk County County Administration Building 50 Colbourne Street, South Simcoe, Ontario N3Y 4H3 Attention: Frank Sams, Manager, Parks Facilities and Recreation Dear Mr. Sams, Re: Final Situational Analysis – Norfolk County Parks, Facilities and Recreation Master Plan and Feasibility Study LEES+Associates in partnership with F.J. Galloway Associates Inc. and Nicholson Sheffield Architects Inc., is pleased to submit the final Situational Analysis for the Norfolk County Parks, Facilities and Recreation Master Plan and Feasibility Study. We have incorporated a wide range of background information, trends and best practices, empirical observations, and input through multiple consultation methods to develop this final analysis. It represents a distillation of these inputs into a document that has also set the stage for developing a community-driven vision and principles to guide future parks and recreation decision making in the County. We are pleased to submit the final Situational Analysis, along with the Final Master Plan and Feasibility Study. Yours Truly, Erik Lees, BLA, CSLA, MCIP, RPP LEES+Associates Contact Information: 509-318 Homer St, Vancouver BC Canada, V6B 2V2 | p: 604.899.3806 | f: 604.899.3805 51 Wolseley Street, Toronto ON Canada, M5T 1A4 | p: 416.645.7033 | f: 416.645.7046 [email protected] | www.elac.ca Norfolk County – Situational Analysis LEES+Associates - i - Norfolk County – Situational Analysis CONTENTS SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS .................................................................................. -

Brantgate PENN ENERGY RENEWABLES, LTD

PENN ENERGY RENEWABLES, LTD. Consultation Report In support of an application for a Renewable Energy Approval (REA) Pursuant to Ontario Regulation 359/09 For the Penn Energy – Brantgate SOLAR ENERGY FACILITY FIT Contract No. F-001576-SPV-130-505 FIT Application No. FIT-FCELIHJ In the County of Brant ONTARIO, CANADA October 23, 2012 Canadian Office: 1 Yonge Street, Suite 1801, Toronto, ON M5E 1W7 U.S. Headquarters: 620 Righters Ferry Road, Bala Cynwyd, PA 19004 Telephone: 610-668-0300 www.PennEnergyRenewables.com Ontario Renewable Energy Approval Project: Penn Energy - Brantgate Consultation Report (CR) Page 2 of 47 A note regarding REA application requirements and additional Project Information: This document is one component of a series of reports and other related documents that, collectively, constitute a complete Renewable Energy Approval (“REA”) application package which will be submitted to the Ministry of the Environment (“MOE”) for review and approval. As such, this report is intended to compliment the other documents and may reference and/or rely upon information contained in them; therefore, the contents herein should not be considered independently. Notice: This document has been prepared solely for the use of Penn Energy Renewables, Ltd. (“Penn”) as part of the REA process in accordance with Ontario Regulation 359/09. It is in DRAFT form and subject to further revision. The content of this document is not intended for the use of – nor is it intended to be relied upon by – any other person, firm or corporation. Penn denies any liability whatsoever to other parties for damages or injury suffered by such third party arising from use of this document by them. -

To Continue Reading the Complete Article Click Here

SIMCOE REFORMER, WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 19, 2008 – 3 YESTERDAY AT THE PUMPS Renton 80.9 Walsingham 79.9 Delhi 80.2 79.9 Simcoe LOCALNEWS REPORT GAS PRICES TO 426-5710 EXT. 137 Energy symposium slated for Jarvis NUKES IN NANTICOKE PROMISES TO BE HOT TOPIC Monte Sonnenberg SIMCOE REFORMER Local residents who want to get up to speed on energy issues affecting Nor- folk, Haldimand and the rest of Ontario are invited to take a crash course in Jarvis later this week. Local MPP Toby Barrett has called an energy symposium for this Thurs- day night at the Lions Community Cen- tre in Jarvis. The gathering is a follow- up to a similar event held in Jarvis last year. At that event, the possibility of sit- uating nuclear reactors in the Nanti- coke Industrial Park was the main issue on the agenda. “Toby has been thinking about this for a while,” constituency assistant Rob Willett said. “We always had the idea we would revisit that one. Some of the same faces will be there and some will not be. Greenpeace, for example, will not be there.” Greenpeace representative Shawn- Patrick Stensil is an outspoken critic of ASHLEY HOUSE / STAFF Kelby Balch plays with her dog Buttons after school. It’s the little things like this that keep the teen, who is suffering from a neurological disease, Ontario’s increasing reliance on nucle- positive. ar power. He attended last year’s sym- posium in Jarvis but will not be able to attend this week due to a scheduling conflict. Expected to make the case ‘I know things will get better eventually’ against nuclear power in his stead is the Canadian Environmental Law Asso- ciation.