Aliphatic Nitriles Final AEGL Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethyl Glucuronide III Enzyme Immunoassay Is Intended for the • This Test Is for in Vitro Diagnostic Use Only

LZI Ethyl Glucuronide III (200) Enzyme Immunoassay – EU Only For In Vitro Diagnostic Use Only 8ºC 0530c (100/37.5 mL R1/R2 Kit) 0531c (1000/375 mL R /R Kit) 1 2 2ºC Lin-Zhi International, Inc. Intended Use Precautions and Warning The LZI Ethyl Glucuronide III Enzyme Immunoassay is intended for the • This test is for in vitro diagnostic use only. Harmful if swallowed. qualitative and semi-quantitative determination of ethyl glucuronide in human • Reagent contains sodium azide as a preservative, which may form explosive urine at the cutoff value of 200 ng/mL when calibrated against ethyl compounds in metal drain lines. When disposing such reagents or wastes, glucuronide. The assay is designed for use with a number of automated clinical always flush with a large volume of water to prevent azide build-up. See chemistry analyzers. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Bulletin: Explosive Azide The semi-quantitative mode is for purposes of (1) enabling laboratories to Hazards (20). determine an appropriate dilution of the specimen for confirmation by a • Do not use the reagents beyond their expiration dates. confirmatory method such as gas or liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS or LC/MS) or (2) permitting laboratories to establish quality control Reagent Preparation and Storage procedures. The reagents are ready-to-use. No reagent preparation is required. All assay components should be refrigerated at 2-8ºC when not in use. The assay provides only a preliminary analytical result. A more specific alternative analytical chemistry method must be used in order to obtain a Specimen Collection and Handling confirmed analytical result. -

Transport of Dangerous Goods

ST/SG/AC.10/1/Rev.16 (Vol.I) Recommendations on the TRANSPORT OF DANGEROUS GOODS Model Regulations Volume I Sixteenth revised edition UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 2009 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ST/SG/AC.10/1/Rev.16 (Vol.I) Copyright © United Nations, 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may, for sales purposes, be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from the United Nations. UNITED NATIONS Sales No. E.09.VIII.2 ISBN 978-92-1-139136-7 (complete set of two volumes) ISSN 1014-5753 Volumes I and II not to be sold separately FOREWORD The Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods are addressed to governments and to the international organizations concerned with safety in the transport of dangerous goods. The first version, prepared by the United Nations Economic and Social Council's Committee of Experts on the Transport of Dangerous Goods, was published in 1956 (ST/ECA/43-E/CN.2/170). In response to developments in technology and the changing needs of users, they have been regularly amended and updated at succeeding sessions of the Committee of Experts pursuant to Resolution 645 G (XXIII) of 26 April 1957 of the Economic and Social Council and subsequent resolutions. -

Background Material:1997-11-12 Diethyl Sulfate As a Federal

DIETHYL SULFATE Diethyl sulfate is a federal hazardous air pollutant and was identified as a toxic air contaminant in April 1993 under AB 2728. CAS Registry Number: 64-67-5 (C2H5)2SO4 Molecular Formula: C4H10O4S Diethyl sulfate is a colorless, moderately viscous, oily liquid with a peppermint odor. It is miscible with alcohol and ether. Diethyl sulfate decomposes into ethyl hydrogen sulfate and alcohol upon heating or in hot water (NTP, 1991). Physical Properties of Diethyl Sulfate Synonyms: sulfuric acid diethyl ester; ethyl sulfate; diethyl sulphate Molecular Weight: 154.19 Boiling Point: 209.5 oC Melting Point: -25 oC Flash Point: 104 oC Vapor Density: 5.31 (air = 1) Density/Specific Gravity: 1.1774 at 20/4 oC (water = 1) Vapor Pressure: 1 mm Hg at 47 oC Conversion Factor: 1 ppm = 6.31 mg/m3 (HSDB, 1991; Merck, 1983; U.S. EPA, 1994a) SOURCES AND EMISSIONS A. Sources Diethyl sulfate is used as an alkylating agent, and to convert hydrogen compounds such as phenols, amines, and thiols to their corresponding ethyl derivatives. Diethyl sulfate can also be used in the preparation of intermediates and products in surfactants, dyes, agricultural chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and other specialty products (NTP, 1991). It has also been detected as a contaminant in thiophosphate insecticides (HSDB, 1991). B. Emissions No emissions of diethyl sulfate from stationary sources in California were reported, based on data obtained from the Air Toxics “Hot Spots” Program (AB 2588) (ARB, 1997b). Toxic Air Contaminant Identification List Summaries - ARB/SSD/SES September 1997 389 Diethyl Sulfate C. Natural Occurrence No information about the natural occurrence of diethyl sulfate was found in the readily- available literature. -

The Application of Ethyl Glucuronide and Ethyl Sulphate

The Application of Ethyl Glucuronide and Ethyl Sulphate in a Forensic Setting Jennifer Button Forensic Specialist (Toxicology) Thermofisher UK Summer Symposium 2011 London - QEIICC - Tuesday 7th June © Jenny Button Overview • Alcohol biomarkers • Application in forensic settings – Post mortem – Investigation of DFSA • Limitations of EtG & EtS – False positives – Synthesis & degradation • Alternative Matrices – Serum, vitreous, oral fluid, hair © Jenny Button Ethanol Analysis • The detection period is very short • BAC reduces by 10-25mg% per hour • A BAC of 80mg% can be 0 within a few hours **Low sensitivity for recent drinking!** • Patients in detox could drink at times when testing was unlikely, due to the rapid excretion of alcohol © Jenny Button Alcohol Biomarkers “Alcohol biomarkers are physiological indicators of alcohol exposure or ingestion and may reflect the presence of an alcohol use disorder” Substance Abuse Treatment Advisory. Sept 2006, Vol 5, Issue 4. © Jenny Button Alcohol Biomarkers 2 Types: • Indirect – Detect toxic effect of heavy alcohol use on organ systems & body chemistry GGT, AST, ASL, MCV, CDT, 5HTOL • Direct – Measure alcohol exposure or use (Analytes of alcohol metabolism) PEth, FAEEs, EtG, EtS © Jenny Button Use of Biomarkers Clinical Settings: • Screening for alcohol problems • Documenting abstinence • Identifying relapse to drinking • Motivating change in drinking behavior • Evaluating interventions for alcohol problems • Conditional liver transplantation Forensic Settings: • Differentiation of anti-mortem -

A Wearable Biochemical Sensor for Monitoring Alcohol Consumption

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN A wearable biochemical sensor for monitoring alcohol consumption lifestyle through Ethyl glucuronide Received: 01 December 2015 Accepted: 29 February 2016 (EtG) detection in human sweat Published: 21 March 2016 Anjan Panneer Selvam1,2, Sriram Muthukumar2, Vikramshankar Kamakoti1 & Shalini Prasad1 We demonstrate for the first time a wearable biochemical sensor for monitoring alcohol consumption through the detection and quantification of a metabolite of ethanol, ethyl glucuronide (EtG). We designed and fabricated two co-planar sensors with gold and zinc oxide as sensing electrodes. We also designed a LED based reporting for the presence of EtG in the human sweat samples. The sensor functions on affinity based immunoassay principles whereby monoclonal antibodies for EtG were immobilized on the electrodes using thiol based chemistry. Detection of EtG from human sweat was achieved through chemiresistive sensing mechanism. In this method, an AC voltage was applied across the two coplanar electrodes and the impedance across the sensor electrodes was measured and calibrated for physiologically relevant doses of EtG in human sweat. EtG detection over a dose concentration of 0.001–100 μg/L was demonstrated on both glass and polyimide substrates. Detection sensitivity was lower at 1 μg/L with gold electrodes as compared to ZnO, which had detection sensitivity of 0.001 μg/L. Based on the detection range the wearable sensor has the ability to detect alcohol consumption of up to 11 standard drinks in the US over a period of 4 to 9 hours. Alcohol (ethanol) is the most abused drug worldwide. Alcohol abuse affects over 18.5 million adults in the U.S., costing society over $200 billion annually in lost productivity, health care expenditures, motor vehicle accidents, crime and other related costs1. -

![United States Patent (19) [11] 3,932,402 Norell (45) Jan](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6379/united-states-patent-19-11-3-932-402-norell-45-jan-626379.webp)

United States Patent (19) [11] 3,932,402 Norell (45) Jan

United States Patent (19) [11] 3,932,402 Norell (45) Jan. 13, 1976 54 PREPARATION OF SYM-TRAZINES BY 3,071,586 111963 Sandner et al...................... 260/248 TRIMERIZATION OF NITRLES IN 3,095,414 6/1963 Spain hour........................... 260/248 3,238,138 3/1966 Braunwarth et al... ... 260/248 X TRIFLUOROMETHANESULFONIC ACD 3,654, 192 4/1972 Vogel.................................. 260/2 R 75 Inventor: John R. Norell, Bartlesville, Okla. OTHER PUBLICATIONS 73 Assignee: Phillips Petroleum Company, Cool et al., J. Chem. Soc., 1941, pp. 278-282. Bartlesville, Okla. Elderfield, “Heterocyclic Compounds", Vol. 7, Ch. 7, pp. 642, 644 and 686. 22) Filed: June 24, 1974 Migrdichian, "The Chemistry of Organic Cyanogen 21 ) Appl. No.: 482,257 Compounds,' Ch. 17, pp. 356, 357 and 367. (52) U.S. Cl............................................ 260/248 CS Primary Examiner-John M. Ford 51) Int. Cl’........................................ C07D 251/24 58 Field of Search............................... 260/248 CS 57 ABSTRACT Aliphatic and aromatic nitriles are trimerized to sub 56) References Cited stituted symmetrical triazines in the presence of UNITED STATES PATENTS trifluoromethanesulfonic acid. 3,060, 179 lof 1962 Toland................................ 260/248 16 Claims, No Drawings 3,932,402 2 In one embodiment of this invention, the organic PREPARATION OF SYM-TRAZINES BY nitrile is an aliphatic nitrile. The product of this process TRIMERIZATION OF NITRILES IN is a 2,4,6-trialkyl-1,3,5-triazine. TRFLUOROMETHANESULFONIC ACID In another embodiment of this invention, the organic This invention relates to substituted sym-triazines. In 5 nitrile is an aromatic or substituted aromatic nitrile in one aspect it relates to the preparation of alkyl-sub which case the product of the process is a 2,4,6-triaryl stituted sym-triazines. -

TOXICOLOGICAL PROFILE for CYANIDE Date Published

0 010024 ATSDR/TP-88/12 TOXICOLOGICAL PROFILE FOR CYANIDE Date Published - December 1989 ' Prepared by: Syracuse Research Corporation under Contract No. 68-CS-0004 for Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (A TSDR) U.S. Public Health Service in collaboration with U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Technical editing/document preparation by: Oak Ridge National Laboratory under DOE Interagency Agreement No. 1857-B026-Al DISCLAIMER Mention of company name or product does not constitute endorsement by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. FOREWORD The Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act of 1986 (Public Law 99-499) extended and amended the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCI.A or Superfund). This public law (also known as SARA) directed the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) to prepare toxicological profiles for hazardous substances which are most commonly found at facilities on the CERCI.A National Priorities List and which pose the most significant potential threat to human health, as determined by ATSDR and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The list of the 100 most significant hazardous substances was published in the Federal Register on Ap r il 17, 1987. Section 110 (3) of SARA directs the Administrator of ATSDR to prepare a toxicological profile for each substance on the list. Each profile must include the following content: "(A) An examination, summary, and interpretation of available toxicological information and epidemiologic evaluations on a hazardous substance in order to ascertain the levels of significant human exposure for the substance and the associated acute, subacute , and chronic health effects. -

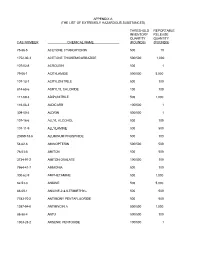

The List of Extremely Hazardous Substances)

APPENDIX A (THE LIST OF EXTREMELY HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCES) THRESHOLD REPORTABLE INVENTORY RELEASE QUANTITY QUANTITY CAS NUMBER CHEMICAL NAME (POUNDS) (POUNDS) 75-86-5 ACETONE CYANOHYDRIN 500 10 1752-30-3 ACETONE THIOSEMICARBAZIDE 500/500 1,000 107-02-8 ACROLEIN 500 1 79-06-1 ACRYLAMIDE 500/500 5,000 107-13-1 ACRYLONITRILE 500 100 814-68-6 ACRYLYL CHLORIDE 100 100 111-69-3 ADIPONITRILE 500 1,000 116-06-3 ALDICARB 100/500 1 309-00-2 ALDRIN 500/500 1 107-18-6 ALLYL ALCOHOL 500 100 107-11-9 ALLYLAMINE 500 500 20859-73-8 ALUMINUM PHOSPHIDE 500 100 54-62-6 AMINOPTERIN 500/500 500 78-53-5 AMITON 500 500 3734-97-2 AMITON OXALATE 100/500 100 7664-41-7 AMMONIA 500 100 300-62-9 AMPHETAMINE 500 1,000 62-53-3 ANILINE 500 5,000 88-05-1 ANILINE,2,4,6-TRIMETHYL- 500 500 7783-70-2 ANTIMONY PENTAFLUORIDE 500 500 1397-94-0 ANTIMYCIN A 500/500 1,000 86-88-4 ANTU 500/500 100 1303-28-2 ARSENIC PENTOXIDE 100/500 1 THRESHOLD REPORTABLE INVENTORY RELEASE QUANTITY QUANTITY CAS NUMBER CHEMICAL NAME (POUNDS) (POUNDS) 1327-53-3 ARSENOUS OXIDE 100/500 1 7784-34-1 ARSENOUS TRICHLORIDE 500 1 7784-42-1 ARSINE 100 100 2642-71-9 AZINPHOS-ETHYL 100/500 100 86-50-0 AZINPHOS-METHYL 10/500 1 98-87-3 BENZAL CHLORIDE 500 5,000 98-16-8 BENZENAMINE, 3-(TRIFLUOROMETHYL)- 500 500 100-14-1 BENZENE, 1-(CHLOROMETHYL)-4-NITRO- 500/500 500 98-05-5 BENZENEARSONIC ACID 10/500 10 3615-21-2 BENZIMIDAZOLE, 4,5-DICHLORO-2-(TRI- 500/500 500 FLUOROMETHYL)- 98-07-7 BENZOTRICHLORIDE 100 10 100-44-7 BENZYL CHLORIDE 500 100 140-29-4 BENZYL CYANIDE 500 500 15271-41-7 BICYCLO[2.2.1]HEPTANE-2-CARBONITRILE,5- -

Scientific Advisory Board

OPCW Scientific Advisory Board Eleventh Session SAB-11/1 11 – 13 February 2008 13 February 2008 Original: ENGLISH REPORT OF THE ELEVENTH SESSION OF THE SCIENTIFIC ADVISORY BOARD 1. AGENDA ITEM ONE – Opening of the Session The Scientific Advisory Board (SAB) met for its Eleventh Session from 11 to 13 February 2008 at the OPCW headquarters in The Hague, the Netherlands. The Session was opened by the Vice-Chairperson of the SAB, Mahdi Balali-Mood. The meeting was chaired by Philip Coleman of South Africa, and Mahdi Balali-Mood of the Islamic Republic of Iran served as Vice-Chairperson. A list of participants appears as Annex 1 to this report. 2. AGENDA ITEM TWO – Adoption of the agenda 2.1 The SAB adopted the following agenda for its Eleventh Session: 1. Opening of the Session 2. Adoption of the agenda 3. Tour de table to introduce new SAB Members 4. Election of the Chairperson and the Vice-Chairperson of the SAB1 5. Welcome address by the Director-General 6. Overview on developments at the OPCW since the last session of the SAB 7. Establishment of a drafting committee 8. Work of the temporary working groups: (a) Consideration of the report of the second meeting of the sampling-and-analysis temporary working group; 1 In accordance with paragraph 1.1 of the rules of procedure for the SAB and the temporary working groups of scientific experts (EC-XIII/DG.2, dated 20 October 1998) CS-2008-5438(E) distributed 28/02/2008 *CS-2008-5438.E* SAB-11/1 page 2 (b) Status report by the Industry Verification Branch on the implementation of sampling and analysis for Article VI inspections; (c) Presentation by the OPCW Laboratory; (d) Update on education and outreach; and (e) Update on the formation of the temporary working group on advances in science and technology and their potential impact on the implementation of the Convention: (i) composition of the group; and (ii) its terms of reference 9. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/75818 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2018-07-08 and may be subject to change. SULFATION VIA SULFITE AND SULFATE DIESTERS AND SYNTHESIS OF BIOLOGICALLY RELEVANT ORGANOSULFATES Een wetenschappelijke proeve op het gebied van de Natuurwetenschappen, Wiskunde en Informatica Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de rector magnificus prof. mr. S. C. J. J. Kortmann, volgens besluit van het college van decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op vrijdag 9 oktober 2009 om 13:00 uur precies door Martijn Huibers geboren op 21 november 1978 te Arnhem Promotor: Prof. dr. Floris P. J. T. Rutjes Copromotor: Dr. Floris L. van Delft Manuscriptcommissie: Prof. dr. ir. Jan C. M. van Hest Prof. dr. Binne Zwanenburg Dr. Martin Ostendorf (Schering‐Plough) Paranimfen: Laurens Mellaard Eline van Roest Het in dit proefschrift beschreven onderzoek is uitgevoerd in het kader van het project “Use of sulfatases in the production of sulfatated carbohydrates and steroids”. Dit project is onderdeel van het Integration of Biosynthesis and Organic Synthesis (IBOS) programma, wat deel uitmaakt van het Advanced Chemical Technologies for Sustainability (ACTS) platform van de Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (NWO). Cofinancierders zijn Schering‐Plough en Syncom. ISBN/EAN: 978‐94‐90122‐51‐5 Drukkerij: Gildeprint Drukkerijen, Enschede Omslagfoto: Martijn Huibers i.s.m. Maarten van Roest Omslagontwerp: Martijn Huibers en Gildeprint Drukkerijen Vermelding van een citaat (onderaan kernpagina's 1 tot en met 112) betekent niet per se dat de auteur van dit proefschrift zich daarbij aansluit, maar dat de uitspraak interessant is, prikkelend is, en/of betrekking heeft op de wetenschap in het algemeen of dit promotieonderzoek in het bijzonder. -

House Fly Attractants and Arrestante: Screening of Chemicals Possessing Cyanide, Thiocyanate, Or Isothiocyanate Radicals

House Fly Attractants and Arrestante: Screening of Chemicals Possessing Cyanide, Thiocyanate, or Isothiocyanate Radicals Agriculture Handbook No. 403 Agricultural Research Service UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Contents Page Methods 1 Results and discussion 3 Thiocyanic acid esters 8 Straight-chain nitriles 10 Propionitrile derivatives 10 Conclusions 24 Summary 25 Literature cited 26 This publication reports research involving pesticides. It does not contain recommendations for their use, nor does it imply that the uses discussed here have been registered. All uses of pesticides must be registered by appropriate State and Federal agencies before they can be recommended. CAUTION: Pesticides can be injurious to humans, domestic animals, desirable plants, and fish or other wildlife—if they are not handled or applied properly. Use all pesticides selectively and carefully. Follow recommended practices for the disposal of surplus pesticides and pesticide containers. ¿/áepé4áaUÁí^a¡eé —' ■ -"" TMK LABIL Mention of a proprietary product in this publication does not constitute a guarantee or warranty by the U.S. Department of Agriculture over other products not mentioned. Washington, D.C. Issued July 1971 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 25 cents House Fly Attractants and Arrestants: Screening of Chemicals Possessing Cyanide, Thiocyanate, or Isothiocyanate Radicals BY M. S. MAYER, Entomology Research Division, Agricultural Research Service ^ Few chemicals possessing cyanide (-CN), thio- cyanate was slightly attractive to Musca domes- eyanate (-SCN), or isothiocyanate (~NCS) radi- tica, but it was considered to be one of the better cals have been tested as attractants for the house repellents for Phormia regina (Meigen). -

United States Patent Office 2,969,402 Patented Jan

United States Patent Office 2,969,402 Patented Jan. 24, 1961 2 preferred. In a more preferred aspect the upper tem 2,969,402 perature is about 10 C. The ratio of the three components, i.e., alkaline earth PREPARATION OF CATALYSTS FOR THE POLY metal hexammoniate, olefin oxide, and organic nitrile, MERIZATION OF EPOXDES can be varied over a wide range in the preparation of the Fred N. Hill, South Charleston, and John T. Fitzpatrick novel catalysts. The reaction is conducted, as indicated and Frederick E. Bailey, Jr., Charleston, W. Va., as previously, in an excess liquid ammonia medium. Thus, signors to Union Carbide Corporation, a corporation active catalysts can be prepared by employing from about of New York 0.3 to 1.0 mol of olefin oxide per mol of metal hexam No Drawing. Filed Dec. 29, 1958, Ser. No. 783,100 0. moniate, and from about 0.2 to 0.8 mol of organic nitrile per mol of metal hexammoniate. Extremely active 12 Claims. (CI. 260-632) catalyst can be prepared by employing from about 0.4 to 1.0 mol of olefin oxide per mol of metal hexammoniate, This invention relates to the preparation of composi and from about 0.3 to 0.6 mol of organic nitrile per mol tions which are catalytically active for the polymerization 5 of metal hexammoniate. It should be noted that the of epoxide compounds which contain a cyclic group com alkaline earth metal hexammoniate, M(NH3)6 wherein posed of two carbon atoms and one oygen atom. M can be calcium, barium, or strontium, contains alkaline Various divalent metal amides, H2N-M-NH2, and earth metal in the zero valence state.