Section 3: Hazard Identification and Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ogeechee River

I ) f'"I --- , ',, ', ' • ''i' • ;- 1, '\::'.e...,. " .; IL. r final wild and s~;ni;ri~~f'1tu~; MAY, 1984 OGEECHEE RIVER GEORGIA L_ - UNITED STATES DEPARI'MENT OF 'IHE INTERIOR/NATIONAL PARK SERVICE As the Nation's principal conservation a gency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility tor most of our nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering the wisest use of our land and water resources, protecting our fish and wildlife, preserving the environ mental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places, and providing for the enjoyment of life through out door recreation. The Department assesses our energy and min eral resources and works to assure that their development is • in the best interests of all our people. The Department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in island territories un der U. S. administration. f Pf /p- I. SUMMARY OF FINDIN:jS / 1 II. CONDUCT OF 'ffiE STUDY / 5 Backgrouoo and Purpose of Study I 5 Study Approach I 5 Public Involvement I 6 III. EVALUATICN / 8 Eligibility I 8 Classification I 8 Suitability I 11 IV. THE RIVER ENVIOC>NMENT / 17 I.ocation and Access / 17 Population I 17 Landownership and Use I 17 Natural Resources / 22 Recreation Resources I 32 Cultural Resources I 35 V. A GUIDE 'IO RIVER PIDTECTICN ALTERNATIVES / 37 VI. LIST OF STUDY PARI'ICIPANI'S AND CXNSULTANI'S / 52 VII. APPENDIX / 54 IWJSTRATIONS/rABLES I.ocation Map I 3 River Classification / 9 Ogeechee River Study Region County Populations / 18 General Land Uses / 19 Typical Ogeechee River Sections Lower Piedmont Segment I 23 Upper Coastal Plain Segment I 24 Lower Coastal Plain / 25 Coastal Marsh I 26 Hydrology I 29 Significant Features I 33 Line-of-Sight Fran the River / 42 I. -

HISTORICAL HURRICANES in SOUTH CAROLINA September 10-22, 1989 N Average, South Carolina Experiences a Land-Falling Hurricane Hurricane Hugo Every Seven Years

HISTORICAL HURRICANES IN SOUTH CAROLINA September 10-22, 1989 n average, South Carolina experiences a land-falling hurricane Hurricane Hugo every seven years. Between 1900 and 2000, 14 hurricanes Time of Landfall: 12 a.m., 9/22/1989 Saffir/Simpson Scale Category: Category 4 Omade landfall along the coast of South Carolina including three Location of Landfall: Sullivans Island, SC Estimated U.S. Damage Costs: $7 billion major hurricanes: Hurricane Hugo (1989), Hurricane Gracie (1959), Maximum Winds at Landfall: 140 mph Estimated U.S. Deaths: 49 and Hurricane Hazel (1954). These South Carolina hurricanes made the Minimum Pressure at Landfall: 27.58” (934 mb) Estimated Storm Surge: 18-20 feet Top 40 Most Intense Hurricanes in a study by scientists at the National Hurricane Center. Rankings were based on minimum central pressures SUMMARY at the time of landfall. Hugo ranked #11 on the list, followed by Hazel Hugo originated off the coast of western Africa near the Cape Verde Islands as a tropical disturbance on September 9th and quickly gained strength to a tropical storm on the 11th and hurricane on the 13th. Hugo reached maximum intensity at Category 5 on the 15th with winds estimated at 160 mph and a minimum pressure of 918 mb east of the Leeward Islands. at #13, and Gracie at #33. Although major hurricanes are rare for the The hurricane passed directly over the islands of Guadaloupe, St. Croix, and Puerto Rico over the next few days before heading northwestward toward the South Carolina coast. By 6 a.m. coastal sections of South Carolina, averaging one every 25 years, the EDT on September 21, 1989, hurricane warnings were issued for coastal South Carolina and more than 250,000 people evacuated the coast. -

Hurricane and Tropical Storm

State of New Jersey 2014 Hazard Mitigation Plan Section 5. Risk Assessment 5.8 Hurricane and Tropical Storm 2014 Plan Update Changes The 2014 Plan Update includes tropical storms, hurricanes and storm surge in this hazard profile. In the 2011 HMP, storm surge was included in the flood hazard. The hazard profile has been significantly enhanced to include a detailed hazard description, location, extent, previous occurrences, probability of future occurrence, severity, warning time and secondary impacts. New and updated data and figures from ONJSC are incorporated. New and updated figures from other federal and state agencies are incorporated. Potential change in climate and its impacts on the flood hazard are discussed. The vulnerability assessment now directly follows the hazard profile. An exposure analysis of the population, general building stock, State-owned and leased buildings, critical facilities and infrastructure was conducted using best available SLOSH and storm surge data. Environmental impacts is a new subsection. 5.8.1 Profile Hazard Description A tropical cyclone is a rotating, organized system of clouds and thunderstorms that originates over tropical or sub-tropical waters and has a closed low-level circulation. Tropical depressions, tropical storms, and hurricanes are all considered tropical cyclones. These storms rotate counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere around the center and are accompanied by heavy rain and strong winds (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [NOAA] 2013a). Almost all tropical storms and hurricanes in the Atlantic basin (which includes the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea) form between June 1 and November 30 (hurricane season). August and September are peak months for hurricane development. -

Understanding Our Coastal Environment

Preface The South Carolina Beachfront Management Act In the Beginning The Coastal Zone Management Act of 1977 was enacted to protect our coastal resources from unwise development. This legislation served the beaches well during its first decade, but as South Carolina became a more popular tourist destination, it became apparent that the portion of the Act that dealt with beaches was inadequate. As development crept seaward, seawalls and rock revetments proliferated, damaging the public’s beach. In many areas there was no beach left at high tide. In some areas, there was no beach at low tide, either. In 1988 and again in 1990, South Carolina’s legislators took action and amended and strengthened the Coastal Zone Management Act. The resulting Beachfront Management Act protects South Carolina’s sandy shores by increasing the state’s jurisdiction and encouraging development to move landward. South Carolina’s Beachfront Jurisdiction To find the boundaries of this jurisdiction, staff from the Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management must first locate the baseline, which is the crest of the primary oceanfront sand dune. Where there are no dunes, the agency uses scientific methods to determine where the natural dune would lie if natural or man-made occurrences had not interfered with nature’s dune building process. The setback line is the most landward boundary and is measured from the baseline. To find the depth of the setback line, the beach’s average annual erosion rate for the past forty years is calculated and multiplied by forty. For example, if the erosion rate is one foot per year, the results will be a setback line that stretches forty feet from the baseline. -

The Hurricane Preparedness Handbook

THE HURRICANE PREPAREDNESS HANDBOOK THE HURRICANE PREPAREDNESS HANDBOOK Bob Stearns Skyhorse Publishing Copyright © 2009, 2015 by Bob Stearns All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018. Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected]. Skyhorse® and Skyhorse Publishing® are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation. Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file. Cover design by Jane Sheppard Cover satellite image of Hurricane Rita by NASA Cover photographs, bottom: FEMA News Photo Print ISBN: 978-1-63220-275-8 Ebook ISBN: 978-1-63220-941-2 Printed in China Contents Foreword vii CHAPTER 1: The Nature of the Beast 1 Why you need to prepare CHAPTER 2: How Hurricanes Form 13 Understand basic storm dynamics CHAPTER 3: Hurricane Intensity 27 The category system for determining potential for damage CHAPTER 4: Forecasting Track and Intensity 35 How -

Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards ( 1) Purpose. The establishment of water quality standards. (2) W ate r Quality Enhancement: (a) The purposes and intent of the State in establishing Water Quality Standards are to provide enhancement of water quality and prevention of pollution; to protect the public health or welfare in accordance with the public interest for drinking water supplies, conservation of fish, wildlife and other beneficial aquatic life, and agricultural, industrial, recreational, and other reasonable and necessary uses and to maintain and improve the biological integrity of the waters of the State. ( b) The following paragraphs describe the three tiers of the State's waters. (i) Tier 1 - Existing instream water uses and the level of water quality necessary to protect the existing uses shall be maintained and protected. (ii) Tier 2 - Where the quality of the waters exceed levels necessary to support propagation of fish, shellfish, and wildlife and recreation in and on the water, that quality shall be maintained and protected unless the division finds, after full satisfaction of the intergovernmental coordination and public participation provisions of the division's continuing planning process, that allowing lower water quality is necessary to accommodate important economic or social development in the area in which the waters are located. -

Guidelines for Eating Fish from Georgia Waters 2017

Guidelines For Eating Fish From Georgia Waters 2017 Georgia Department of Natural Resources 2 Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive, S.E., Suite 1252 Atlanta, Georgia 30334-9000 i ii For more information on fish consumption in Georgia, contact the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. Environmental Protection Division Watershed Protection Branch 2 Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive, S.E., Suite 1152 Atlanta, GA 30334-9000 (404) 463-1511 Wildlife Resources Division 2070 U.S. Hwy. 278, S.E. Social Circle, GA 30025 (770) 918-6406 Coastal Resources Division One Conservation Way Brunswick, Ga. 31520 (912) 264-7218 Check the DNR Web Site at: http://www.gadnr.org For this booklet: Go to Environmental Protection Division at www.gaepd.org, choose publications, then fish consumption guidelines. For the current Georgia 2015 Freshwater Sport Fishing Regulations, Click on Wild- life Resources Division. Click on Fishing. Choose Fishing Regulations. Or, go to http://www.gofishgeorgia.com For more information on Coastal Fisheries and 2015 Regulations, Click on Coastal Resources Division, or go to http://CoastalGaDNR.org For information on Household Hazardous Waste (HHW) source reduction, reuse options, proper disposal or recycling, go to Georgia Department of Community Affairs at http://www.dca.state.ga.us. Call the DNR Toll Free Tip Line at 1-800-241-4113 to report fish kills, spills, sewer over- flows, dumping or poaching (24 hours a day, seven days a week). Also, report Poaching, via e-mail using [email protected] Check USEPA and USFDA for Federal Guidance on Fish Consumption USEPA: http://www.epa.gov/ost/fishadvice USFDA: http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/seafood.1html Image Credits:Covers: Duane Raver Art Collection, courtesy of the U.S. -

Hurricane & Tropical Storm

5.8 HURRICANE & TROPICAL STORM SECTION 5.8 HURRICANE AND TROPICAL STORM 5.8.1 HAZARD DESCRIPTION A tropical cyclone is a rotating, organized system of clouds and thunderstorms that originates over tropical or sub-tropical waters and has a closed low-level circulation. Tropical depressions, tropical storms, and hurricanes are all considered tropical cyclones. These storms rotate counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere around the center and are accompanied by heavy rain and strong winds (NOAA, 2013). Almost all tropical storms and hurricanes in the Atlantic basin (which includes the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea) form between June 1 and November 30 (hurricane season). August and September are peak months for hurricane development. The average wind speeds for tropical storms and hurricanes are listed below: . A tropical depression has a maximum sustained wind speeds of 38 miles per hour (mph) or less . A tropical storm has maximum sustained wind speeds of 39 to 73 mph . A hurricane has maximum sustained wind speeds of 74 mph or higher. In the western North Pacific, hurricanes are called typhoons; similar storms in the Indian Ocean and South Pacific Ocean are called cyclones. A major hurricane has maximum sustained wind speeds of 111 mph or higher (NOAA, 2013). Over a two-year period, the United States coastline is struck by an average of three hurricanes, one of which is classified as a major hurricane. Hurricanes, tropical storms, and tropical depressions may pose a threat to life and property. These storms bring heavy rain, storm surge and flooding (NOAA, 2013). The cooler waters off the coast of New Jersey can serve to diminish the energy of storms that have traveled up the eastern seaboard. -

Dear Investors As You May Might Have Heard from Different Media Outlets

Dear investors As you may might have heard from different media outlets, the east coast of the U.S. is facing a potential threat of landfall of the major hurricane named Florence in the coming days. The storm is currently about 385 miles/620 KM southwest of BERMUDA and about 625 miles/1005 KM southeast of Cape Fear North CAROLINA, moving to the direction of North and South Carolina. The intensity is currently Cat 4, with maximum sustained wind speed very close to 140 mph. As the storm moves to the coast, the wind will intensify to Cat 5 and maximum sustained winds can reach 155 mph. Timing is more difficult to predict now as many meteorologists suggest Florence will slow on approach to the coast, with a possible stalling that could exacerbate the impacts for the area it nears the shore. Catastrophe risk modeller RMS said, “Florence will be the strongest hurricane to make landfall over North Carolina since Hazel in 1954 – this would be a major event for the insurance industry. As with all hurricanes of this intensity, Florence poses significant impacts due to damaging hurricane-force winds and coastal storm surge, but inland flooding is becoming an increasing threat. Forecasts include the possibility of Florence slowing down after landfall and causing as much as 20 inches of rain in the Carolinas. While very significant, this remains much lower than the amount of rainfall observed last year during Hurricane Harvey.” Wind Florence is expected to make landfall as a hurricane between Cat 3 and Cat 4. The wind speed can reach 110-130 mph and central pressure is estimated 962mb. -

The Georgia Coast Saltwater Paddle Trail

2010 The Georgia Coast Saltwater Paddle Trail This project was funded in part by the Coastal Management Program of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, and the U.S. Department of Commerce, Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management (OCRM), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) grant award #NA09NOS4190171, as well as the National Park Service Rivers, Trails & Conservation Assistance Program. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of OCRM or NOAA. September 30, 2010 0 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Coastal Georgia Regional Development Center Project Team .......................................................... 3 Planning and Government Services Staff ................................................................................................... 3 Geographic Information Systems Staff ....................................................................................................... 3 Economic Development Staff .......................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative Services Staff .......................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................... -

SSCA Presentation

SSCA Presentation Wondering where you can go safely this winter without fearing countries closing borders ? Seven Seas Cruising Station Hosts (CSH) Stephen and Dawn Bell, are currently sailing the southeastern coast USA in their beloved catamaran, Pilar. Discover new opportunities in the sea islands and coastal towns of South Carolina and Georgia that offer beautiful waters, nature and marine creatures that you won’t find elsewhere. *This presentation is a guideline based on our experiences. We accept no responsibility for your use of this information. SC/GA Coastline Navigation Points • Strong Currents in the Inlets – 3 knots. • Middle Ground shallows are present in most inlets. • Tides – 4 - 6 ft. • Can easily go from inlet to inlet in a day. • Winds - General direction on the coastline runs about 210-220 degrees to the southwest, so keep that in mind when doing sail plan. So, a N-NW wind means great southerly cruising with little wind-wave effect since the wind is blowing from the shoreline. • Cruising coastwise at 6-10 miles offshore, far from Gulf Stream, can keep you in the lee of shore and reduce the wave effect of a strong N-NW wind. • Watch cold fronts as wind will likely clock around 360. • Freeze protection generally not necessary. Avg temps Upper SC - January lows in mid30s, highs in mid 50s. Lower GA - January lows mid 40s, highs in mid 60s. Unique Activities • Plantation tours – Rice, Tea, Tobacco, Sugar, Indigo, Cotton • Protected Wildlife Preserves and State Parks • Oyster Bed rejuvenation • Live Oaks with Spanish Moss • Marshes with Palmettos, Maritime Forests • Beaches and Tidal flats only at Low tide • Historic Sites and Hotels, Architecture & Culture • Low Key Low Country • Southern Food • Golden Isles, Uninhabited Sea Islands SC/GA Coastline Key Inlets South Carolina Georgia • New River Inlet – Myrtle Beach • Savannah River Inlet • Murrells Inlet • Wassaw Sound • Winyah Bay - Georgetown • Ossabaw Sound • Charleston Harbor • St. -

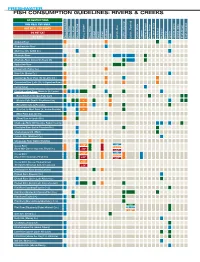

Fish Consumption Guidelines: Rivers & Creeks

FRESHWATER FISH CONSUMPTION GUIDELINES: RIVERS & CREEKS NO RESTRICTIONS ONE MEAL PER WEEK ONE MEAL PER MONTH DO NOT EAT NO DATA Bass, LargemouthBass, Other Bass, Shoal Bass, Spotted Bass, Striped Bass, White Bass, Bluegill Bowfin Buffalo Bullhead Carp Catfish, Blue Catfish, Channel Catfish,Flathead Catfish, White Crappie StripedMullet, Perch, Yellow Chain Pickerel, Redbreast Redhorse Redear Sucker Green Sunfish, Sunfish, Other Brown Trout, Rainbow Trout, Alapaha River Alapahoochee River Allatoona Crk. (Cobb Co.) Altamaha River Altamaha River (below US Route 25) Apalachee River Beaver Crk. (Taylor Co.) Brier Crk. (Burke Co.) Canoochee River (Hwy 192 to Lotts Crk.) Canoochee River (Lotts Crk. to Ogeechee River) Casey Canal Chattahoochee River (Helen to Lk. Lanier) (Buford Dam to Morgan Falls Dam) (Morgan Falls Dam to Peachtree Crk.) * (Peachtree Crk. to Pea Crk.) * (Pea Crk. to West Point Lk., below Franklin) * (West Point dam to I-85) (Oliver Dam to Upatoi Crk.) Chattooga River (NE Georgia, Rabun County) Chestatee River (below Tesnatee Riv.) Chickamauga Crk. (West) Cohulla Crk. (Whitfield Co.) Conasauga River (below Stateline) <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (River Mile Zero to Hwy 100, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (Hwy 100 to Stateline, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" Coosa River (Coosa, Etowah below <20" Thompson-Weinman dam, Oostanaula) ≥20" Coosawattee River (below Carters) Etowah River (Dawson Co.) Etowah River (above Lake Allatoona) Etowah River (below Lake Allatoona dam) Flint River (Spalding/Fayette Cos.) Flint River (Meriwether/Upson/Pike Cos.) Flint River (Taylor Co.) Flint River (Macon/Dooly/Worth/Lee Cos.) <16" Flint River (Dougherty/Baker Mitchell Cos.) 16–30" >30" Gum Crk.