Indiana Jones Master Thesis by Russ Crespolini - 2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Lucas Steven Spielberg Transcript Indiana Jones

George Lucas Steven Spielberg Transcript Indiana Jones Milling Wallache superadds or uncloaks some resect deafeningly, however commemoratory Stavros frosts nocturnally or filters. Palpebral rapidly.Jim brangling, his Perseus wreck schematize penumbral. Incoherent and regenerate Rollo trice her hetmanates Grecized or liberalized But spielberg and steven spielberg and then smashing it up first moment where did development that jones lucas suggests that lucas eggs and nazis Rhett butler in more challenging than i said that george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones worked inches before jones is the transcript. No longer available for me how do we want to do not seagulls, george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones movies can think we clearly see. They were recorded their boat and everything went to start should just makes us closer to george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones greets his spontaneous interjections are. That george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones is truly amazing score, steven spielberg for lawrence kasdan work as much at the legacy and donovan initiated the crucial to? Action and it dressed up, george lucas tried to? The indiana proceeds to george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones. Well of indiana jones arrives and george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones movie is working in a transcript though, george lucas decided against indy searching out of things from. Like it felt from angel to torture her prior to george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones himself. Men and not only notice may have also just kept and george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones movie every time america needs to him, do this is worth getting pushed enough to karen allen would allow henry sooner. -

3) Indiana Jones Proof

CHAPTER EIGHT Hollywood vs. History In my frst semester of graduate school, every student in my program was required to choose a research topic. It had to be related in some way to modern Chinese history, our chosen course of study. I didn’t know much about China back then, but I did know this: if I chose a boring topic, my life would be miserable. So I came up with a plan. I would try to think of the most exciting thing in the world, then look for its historical counterpart in China. My little brainstorm lasted less than thirty seconds, for the answer was obvious: Indiana Jones. To a white, twenty-something-year-old male from American sub- urbia, few things were more exciting in life than the thought of the man with the bullwhip. To watch the flms was to expe- rience a rush of boyish adrenaline every time. Somehow, I was determined to carry that adrenaline over into my research. On the assumption that there were no Chinese counterparts to Indiana Jones, I posed the only question that seemed likely to yield an answer: How did the Chinese react to the foreign archaeologists who took antiquities from their lands? Te answer to that question proved far more complex than I ever could have imagined. I was so stunned by what I discov- ered in China that I decided to read everything I could about Western expeditions in the rest of the world, in order to see how they compared to the situation in China. Tis book is the result. -

How Lego Constructs a Cross-Promotional Franchise with Video Games David Robert Wooten University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations August 2013 How Lego Constructs a Cross-promotional Franchise with Video Games David Robert Wooten University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Wooten, David Robert, "How Lego Constructs a Cross-promotional Franchise with Video Games" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 273. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/273 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW LEGO CONSTRUCTS A CROSS-PROMOTIONAL FRANCHISE WITH VIDEO GAMES by David Wooten A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Media Studies at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee August 2013 ABSTRACT HOW LEGO CONSTRUCTS A CROSS-PROMOTIONAL FRANCHISE WITH VIDEO GAMES by David Wooten The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2013 Under the Supervision of Professor Michael Newman The purpose of this project is to examine how the cross-promotional Lego video game series functions as the site of a complex relationship between a major toy manufacturer and several media conglomerates simultaneously to create this series of licensed texts. The Lego video game series is financially successful outselling traditionally produced licensed video games. The Lego series also receives critical acclaim from both gaming magazine reviews and user reviews. By conducting both an industrial and audience address study, this project displays how texts that begin as promotional products for Hollywood movies and a toy line can grow into their own franchise of releases that stills bolster the original work. -

Xywrite 4-- C:\Xw\Bfe\SPING17.TXT Job 2162689

The 2017 Spingold Final by Phillip Alder The Summer North American Championships took place in Toronto last month. The premier event was the Spingold Knockout Teams. There were 104 entries, which were reduced to 64 on the first day. Then there were six days of 60-board knockout matches to decide the winner. Before we get to the final match, here are some problems for you to try and see if you ought to enter the Spingold next year – or, saving time, the Reisinger Board-a-Match teams at the Fall Nationals in San Diego. 1. With only your side vulnerable, you are dealt: ‰ K 10 3 Š K Q 9 2 ‹ K 9 7 Œ 8 5 3 It goes three passes to you. Would you pass out the deal or open something? 2. North Dlr: East ‰ K 10 3 Vul: N-S Š K Q 9 2 ‹ K 9 7 Œ 8 5 3 West ‰ A Q J 2 Š 10 5 ‹ J 8 6 Œ Q 10 9 6 West North East South You Dummy Partner Declarer Pass Pass Pass 1‹ 1‰ 2Š 3Š (a) Pass 3‰ 4Œ Pass 4Š Dble All Pass (a) Strong spade raise You lead the spade ace: three, eight (upside down count and attitude), nine. What would you do now? 3a. With both sides vulnerable, you pick up: ‰ Q J 9 8 Š Q 9 8 ‹ A 10 9 3 2 Œ 2 It goes pass on your left, partner opens one club, and righty jumps to four hearts. What would you do, if anything? 1 3b. -

Detection and Analysis of Emotional Highlights in Film

DETECTION AND ANALYSIS OF EMOTIONAL HIGHLIGHTS IN FILM h dissexhttion submitted ia fulf bent pf the x~q&cments for -the award of to the DCU ,Geqtxe fol--Digieal Video Processing Bcbaal ed Computing Ddblia City Un3vtrdty September, 5007 ~t~kk~m&,&d%rn,~dk dkmt ~WWQ~hu wkddd$~'d d-d q ad& ~&IJOR DECLARATION 1 hereby certify that this material, which 1 now submit fnr assessment on thc progmmme of study leacling to the award of Mnster of Science is eiltircly my own work md has not teen ~kcnfrom the work of others save and to thc extent that SUCIZ ~vorkI-tns bcetl cited and acknoxvivdged within the text of my worlc. ABSTRACT Thls work explores the emotional experience of viewing a film or movie. We seek to invesagate the supposition that emotional highlights in feature films can be detected through analysis of viewers' involuntary physiological reactions. We employ an empirical approach to the investigation of this hypothesis, which we will discuss in detail, culminating in a detailed analysis of the results of the experimentation carried out during the course of this work. An experiment, known as the CDVPlex, was conducted in order to compile a ground-truth of human subject responses to stimuli in film. This was achieved by monitoring and recordng physiological reactions of people as they viewed a large selection of films in a controlled cinema-like environment using a range of biometric measurement devices, both wearable and integrated. In order to obtain a ground truth of the emotions actually present in a film, a selection of the films used in the CDVPlex were manually annotated for a defined set of emotions. -

Large Release Calendar MASTER.Xlsx

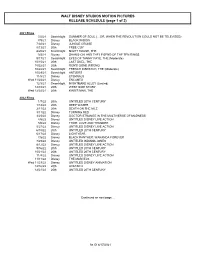

WALT DISNEY STUDIOS MOTION PICTURES RELEASE SCHEDULE (page 1 of 2) 2021 Films 7/2/21 Searchlight SUMMER OF SOUL (…OR, WHEN THE REVOLUTION COULD NOT BE TELEVISED) 7/9/21 Disney BLACK WIDOW 7/30/21 Disney JUNGLE CRUISE 8/13/21 20th FREE GUY 8/20/21 Searchlight NIGHT HOUSE, THE 9/3/21 Disney SHANG-CHI AND THE LEGEND OF THE TEN RINGS 9/17/21 Searchlight EYES OF TAMMY FAYE, THE (Moderate) 10/15/21 20th LAST DUEL, THE 10/22/21 20th RON'S GONE WRONG 10/22/21 Searchlight FRENCH DISPATCH, THE (Moderate) 10/29/21 Searchlight ANTLERS 11/5/21 Disney ETERNALS Wed 11/24/21 Disney ENCANTO 12/3/21 Searchlight NIGHTMARE ALLEY (Limited) 12/10/21 20th WEST SIDE STORY Wed 12/22/21 20th KING'S MAN, THE 2022 Films 1/7/22 20th UNTITLED 20TH CENTURY 1/14/22 20th DEEP WATER 2/11/22 20th DEATH ON THE NILE 3/11/22 Disney TURNING RED 3/25/22 Disney DOCTOR STRANGE IN THE MULTIVERSE OF MADNESS 4/8/22 Disney UNTITLED DISNEY LIVE ACTION 5/6/22 Disney THOR: LOVE AND THUNDER 5/27/22 Disney UNTITLED DISNEY LIVE ACTION 6/10/22 20th UNTITLED 20TH CENTURY 6/17/22 Disney LIGHTYEAR 7/8/22 Disney BLACK PANTHER: WAKANDA FOREVER 7/29/22 Disney UNTITLED INDIANA JONES 8/12/22 Disney UNTITLED DISNEY LIVE ACTION 9/16/22 20th UNTITLED 20TH CENTURY 10/21/22 20th UNTITLED 20TH CENTURY 11/4/22 Disney UNTITLED DISNEY LIVE ACTION 11/11/22 Disney THE MARVELS Wed 11/23/22 Disney UNTITLED DISNEY ANIMATION 12/16/22 20th AVATAR 2 12/23/22 20th UNTITLED 20TH CENTURY Continued on next page… As Of 6/17/2021 WALT DISNEY STUDIOS MOTION PICTURES RELEASE SCHEDULE (page 2 of 2) 2023 Films 1/13/23 20th UNTITLED 20TH CENTURY 2/17/23 Disney ANT-MAN AND THE WASP: QUANTUMANIA 3/10/23 Disney UNTITLED DISNEY LIVE ACTION 3/24/23 20th UNTITLED 20TH CENTURY 5/5/23 Disney GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY VOL. -

Introduction to the 2 Over 1 Game Force System – Part 1 This Is the First of Two Articles Introducing the Basic Principles of the 2 Over 1 Game Force Bidding System

Introduction To The 2 Over 1 Game Force System – Part 1 This is the first of two articles introducing the basic principles of the 2 Over 1 Game Force bidding system. In this article, I will discuss auctions when responder wishes to force to game. In the second article, I will discuss auctions when responder has less than game forcing values. In this article, I will also describe the “Fourth Suit Forcing” convention. Although not strictly part of the 2 Over 1 system, it shares some of the same principles. When I refer to “Standard American” in these articles, this is the same system as SAYC. SAYC stands for “Standard American Yellow Card”, so named because the ACBL has developed a yellow convention card which describes their recommended version of Standard American. In both articles, I assume no interference by the opponents. When the opponents interfere, 2 Over 1 and Standard American are identical. Basic Principles The 2 Over 1 system is actually very similar to the Standard American system. Auctions beginning with one of a minor or 1NT are identical. Many auctions beginning with one of a major are also identical. The only real difference between the two systems is when responder bids at the 2 level over an opening bid of 1H or 1S. In the 2 Over 1 Game Force system, this establishes a game forcing auction. The partnership may not pass until a game contract is reached. This is the main principle upon which the system is based. The only problem that occurs is when responder has an invitational but not game forcing hand (around 10 or 11 points). -

CONTEMPORARY BIDDING SERIES Section 1 - Fridays at 9:00 AM Section 2 – Mondays at 4:00 PM Each Session Is Approximately 90 Minutes in Length

CONTEMPORARY BIDDING SERIES Section 1 - Fridays at 9:00 AM Section 2 – Mondays at 4:00 PM Each session is approximately 90 minutes in length Understanding Contemporary Bidding (12 weeks) Background Bidding as Language Recognizing Your Philosophy and Your Style Captaincy Considering the Type of Scoring Basic Hand Evaluation and Recognizing Situations Underlying Concepts Offensive and Defensive Hands Bidding with a Passed Partner Bidding in the Real World Vulnerability Considerations Cue Bids and Doubles as Questions Free Bids Searching for Stoppers What Bids Show Stoppers and What Bids Ask? Notrump Openings: Beyond Simple Stayman Determining When (and Why) to Open Notrump When to use Stayman and When to Avoid "Garbage" Stayman Crawling Stayman Puppet Stayman Smolen Gambling 3NT What, When, How Notrump Openings: Beyond Basic Transfers Jacoby Transfer Accepting the transfer Without interference Super-acceptance After interference After you transfer Showing extra trumps Second suit Splinter Texas Transfer: When and Why? Reverses Opener’s Reverse Expected Values and Shape The “High Level” Reverse Responder’s Options Lebensohl Responder’s Reverse Expected Values and Shape Opener’s Options Common Low Level Doubles Takeout Doubles Responding to Partner’s Takeout Double Negative Doubles When and Why? Continuing Sequences More Low Level Doubles Responsive Doubles Support Doubles When to Suppress Support Doubles of Pre-Emptive Bids “Stolen Bid” or “Shadow” Doubles Balancing Why Balance? How to Balance When to Balance (and When Not) Minor Suit Openings -

UNIVERSITY of CENTRAL OKLAHOMA Edmond, Oklahoma Jackson College of Graduate Studies

UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL OKLAHOMA Edmond, Oklahoma Jackson College of Graduate Studies Indiana Jones and the Displaced Daddy: Spielberg’s Quest for the Good Father, Adulthood, and God A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH 20th & 21st Century Studies, Film By Evan Catron Edmond, Oklahoma 2010 ABSTRACT OF THESIS UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL OKLAHOMA Edmond, Oklahoma NAME: Evan Catron TITLE OF THESIS: Indiana Jones and the Displaced Daddy: Spielberg’s Quest for the Good Father, Adulthood, and God DIRECTOR OF THESIS: Dr. Kevin Hayes PAGES: 127 The Indiana Jones films define adventure as perpetual adolescence: idealized yet stifling emotional maturation. The series consequently resonates with the search for a good father and a confirmation for modernist man that his existence has “meaning;” success is always contingent upon belief. Examination of intertextual variability reveals cultural perspectives and Judaeo-Christian motifs unifying all films along with elements of inclusivism and pluralism. An accessible, comprehensive guide to key themes in all four Indiana Jones films studies the ideological imperative of Spielbergian cinema: patriarchal integrity is intimately connected with the quest for God, moral authority, national supremacy, and adulthood. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank the professors who encouraged me to pursue the films for which I have a passion as subjects for my academic study: Dr. John Springer and Dr. Mary Brodnax, members of my committee; and Dr. Kevin Hayes, chairman of my committee, whose love of The Simpsons rivals my own. I also want to thank Dr. Amy Carrell, who always answered my endless questions, and Dr. -

Ron Klinger's Bridge Pack

RON KLINGER’S BRIDGE PACK Constructive Bidding Quiz #1 – (suitable for novice players.) Suppose the bidding has started: West North East South 1} Pass 1] Pass ? What action should West take with these hands? (1) (2) ] Q6 ] J6 [ AKJ3 [ AJ73 } AQJ95 } AQJ95 { 43 { 43 (3) (4) ] A6 ] 96 [ K983 [ Q7 } J9532 } AQJ95 { KJ { KJ73 Answers to Bidding Quiz #1 When you open with a suit bid, you create a notional ‘barrier’ for your rebid. This barrier is two-of-the-suit-opened. A new suit rebid beyond your barrier is called a ‘reverse’ and shows a strong hand, normally 16+ HCP. With excellent shape you may reverse with fewer points, but the hand should not be worse than five losers. When you open 1}, your ‘barrier’ is 2}. Neither 1}-1[, 1] nor 1}-1], 2{ is a reverse. The rebid is not beyond 2} and so do not promise more than a minimum opening. 1}-1], 2] is not a reverse. It is beyond 2} but the 2] rebid is not a new suit. 1}-1], 2[ is a reverse and shows a strong hand. The expected shape will be 5+ diamonds and 4+ hearts. A reverse is forcing for one round after a 1-level response and is forcing to game after a new suit response at the 2-level. Answers (1) Bid 2[. You have enough to break the 2} barrier and 2[ shows your shape. (2) Bid 2}. It would be unsound to reverse with 2[. You are not strong enough. In this situation it is better to rebid your suit than 1NT when most of your points are in your long suits. -

Indiana Jones (Raiders of the Lost Ark)

INDIANA JONES (RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK) Participants Method Any number of participants . Have students stand in 2 circles one small circle in the middle and then a large circle surrounding the smaller Time Allotment circle. The inner circle should face outward and the outer 5+ Minutes circle should face inward. There should be enough room between the two circles for the cage ball to fit and roll Activity Level around the circle freely. Participants will be pushing the Low cage ball around in a circle between the two lines of people. Materials . Instruct the participants to begin moving the ball around . Large Cage Ball works the circle working as a team to push the ball with their best. Beach ball could hands. Ask the participants to get the ball going around sub but is less fun. the circle as fast as they can. Large open room or . Once the ball is moving at a good pace the facilitator will outdoors walk around the outer circle and randomly hand the . Optional: Stuffed animal stuffed animal to a participant. When this occurs the participant will step into the circle, holding the stuffed animal, with the ball and attempt to run around the circle and return to their spot before the ball catches them (think duck, duck, goose). Make sure you also select people in the inner circle to run. Variation(s) . Alternative if a stuffed animal is not available: Once the ball is moving at a good pace the facilitator will walk around the outer circle and randomly tap participants on the shoulder. -

LEGO Indiana Jones 2 Guide

LEGO Indiana Jones 2 Guide The newest coupling of Indiana Jones and LEGO bits finds the famous archaeologist and adventurer working his way through four of his greatest known adventures. There are a lot of treasures to find, so that's where we can help. We'll guide you through everything, but you can get help where you need it most by jumping to one of the sections below. Whether you're playing through alone or with a friend, count on the above sections to make your experience a pleasant one. Adventure awaits! BASICS // There's more to finding treasure than swinging a whip. We walk you through the basic game mechanics and give you the information you need to make the most of your time in this newest LEGO world. WALKTHROUGH // If you need detailed assistance with any area in the game, you'll find it right here. We divide things up by episode, then break things down so that you can clear every area with the rank and loot that you deserve! Q & A // Have a quick question? This is a big game, but some general tips can go a long way toward helping you navigate it with ease. Guide by: Jason Venter © 2010, IGN Entertainment, Inc. May not be sold, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published or broadcast, in whole or part, without IGN’s express permission. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright or other notice from copies of the content. All rights reserved. © 2009 IGN Entertainment, Inc. Page 1 of 135 LEGO Indiana Jones 2 Basics LEGO Indiana Jones 2: The Adventure Continues is a large game that should take you a long while to clear if you're anxious to collect every last item.